Living close to water is good for our health: it reduces the risk of premature death, obesity, and has a generally restorative effect on people’s mental and physical health.1 In the city, water is often so near, yet so far. Did you know there are more canals in Birmingham than there are in Venice, but people have been separated from the water by bad urban space? Tallinn has a long coastline but there are very few places in the centre where you can access the sea at all.

Few Tallinners have never visited Noblessner or heard of it. This former industrial harbour is well-located, it features Kai Art Centre, Proto Invention Factory, Põhjala Brewery, offices, living spaces, dineries, the marina, saunas. The Foundry at Noblessner has excellent acoustics and has hosted the performance of Arvo Pärt’s music as well as a concert by hypnogogic pop artist Ariel Pink. What is perhaps more important is the opportunity to walk by the sea (or jump into it)—the area is accessible on foot or by bike. You can even get there by ship and boat. And by car… well, there is no place in Tallinn you could not access by car. The development of Noblessner is still underway. Some historical edifices are being reconstructed, and new buildings are being built. The next section of the sea promenade will be completed, and the marina will widen. Noblessner’s story began when Emanuel Nobel and Arthur Lessner founded a submarine factory here in 1912. By the way, Emanuel Nobel was the nephew of Alfred Nobel.

The current owner and developer of Port Noblessner is BLRT Group. The main spatial design of Noblessner was determined by the 2007 architectural competition won by the Danish office Hvidt & Mølgaard, the 2013 detail plan implemented based on the winning project, and the 2014 housing competition won by architecture office Pluss.

Private development or public space?

Noblessner is a privately owned public space, or pops. These are a common encounter in cities such as London, New York, Toronto, and Rotterdam which have all mapped the locations of their pops’. The Guardian has written how privately owned public space may increasingly be an issue2 in the UK: for example, organising a protest on private grounds for, say, supporting the Ukraine, can be prohibited if some foreign pension fund or sheikh were to forbid it. As long as we recognise these risks and deal with them, we could welcome private interest to contribute to public spaces. As architect David Sim spoke at the Estonian translation launch of Soft City, good public space clearly adds measurable financial value to real estate.

At Noblessner you can sit down and spend time without the need to buy, for example, a coffee. By comparison, Tallinn’s Town Hall Square does not feature public benches for sitting down. In 2021, there was talk in the media that consuming your own drinks on the steps at the marina was prohibited. As it is private property and the steps are situated in front of the outdoor terrace of the restaurant, the prohibition is indeed the right of the owner, if not to say understandable. The outdoor terrace is open during a certain number of months out of the year, and for the rest of the time it is possible to hang out there freely. Moreover, should the private property argument seem too cold, let’s be considerate towards the livelihood of the restaurateurs and their need to pay their staff, especially in this (post)pandemic era.

Cooperation with the city

One of the strongest forces behind developing Noblessner has no doubt been the tight collaboration between the owner and the municipality. An example is Kalaranna Street, without which development of the entire area from Kalarand to Miinisadam would not have come to fruition. This came about when the city still had a city architect. We can only hope that Endrik Mänd will not be the last city architect of Tallinn. There is talk about establishing a tramline to Kalaranna Street. Since this is the wish of the developers of the seaside areas Noblessner, Patarei Sea Fortress, and Hundipea, there is hope it one day may manifest. The climate crisis calls for more public transportation, especially tramlines, in any city. As long as the current car-centric leaders of the Tallinn’s Transport Department and deputy mayor Andrei Novikov remain in office, it is not hard to believe that instead of the tramline, a 1+1 motorway for cars will be injected into a linear park in the region called Pollinator Highway (Putukaväil).

What can we learn from Noblessner?

When the Estonian Association of Architects hosted the Architects’ Council of Europe in Tallinn in 2014, one of the places visited was Noblessner. The visitors were impressed by the site already back then. Estonian architects have increasingly more to offer to the world. The development of Noblessner holds some universal leadership principles that all developers, builders, and clients can follow in order to achieve a high-quality built environment.

The first thing to underline about the success story of Noblessner is the organising of international architecture competitions in 2007 and 2014. The vision drafted by architecture office Hvidt & Mølgaard determined the principles of the structure of the quarter we see realised today, including the shore promenade.

Secondly, the winning housing competition project by architecture office Pluss looked at the task more broadly: streets were emptied of cars and parking was moved underground. This was not a requirement in the competition brief, and no doubt the offered solution was more expensive. Importantly however, the client trusted the work of architects: this is a universal principle for any client to follow any time in any place.

Thirdly, the streetscape was to be enlivened by commercial spaces on the first two floors and diagonal passthroughs at the corners of the buildings.

Fourthly, the windows of all the apartments were designed to open along the street perimeter, providing firefighters the chance to work without having to sacrifice the courtyard to mobile infrastructure.

Lastly, a human-centred approach was adopted in designing the streets and squares of Noblessner. Removing cars from the streets was a critical spatial decision that laid the premise for a human-centred environment and set the cornerstone for the public space concept. For example, the ramp leading to underground parking was moved inside the building to avoid damage to the street.

This is what can happen if development starts from concepts other than parking spots forced upon by the municipality of Tallinn. Unfortunately, the number of parking spots was designed according to the ratio of 600–650 cars per 1,000 persons, as demanded by the transport department of the capital. In comparison: the ratio is 320–350 cars per 1,000 persons in Stockholm, Linköping, Göteborg, and Helsinki. Interestingly, the ratio is 200/1,000 in the centre of Helsinki, and by the sea, next to Kalasatama, a development with 3,000 apartments is underway where the city has placed no demands for parking spaces at all. In the Nordic countries, the number of private cars is diminishing but growing in Tallinn as a result of municipal decisions that favour motorisation. An analysis of the utilisation of parking spaces carried out at Noblessner in 2021 found the ratio there to be 330 cars per 1,000 residents.

What others learn from Noblessner? Ann Virkus, Head of Special Projects at Noblessner, ‘The starting premise for any type of development is a clear understanding of the type of area that is being created. If the plan is to create a versatile, human-centric urban space, make it one where you, your friends and family as citizens would enjoy spending time in. The kind you would like to introduce to your culturally inclined mother as a living space and your entrepreneur friend as the location of his main office.’3

Indrek Allmann, architecture office Pluss, ‘Noblessner was a maverick, bringing into focus public and human-centred urban space. Today, we see the same by default conjunction towards the same standard. Investors experienced with Noblessner that it is possible to sell apartments even when the parking spot is not directly beneath your window and that without explicitly investing into public space, it is hard to achieve a whole that residents appreciate.’4

On the future of Põhja-Tallinn

What do Noblessner, Kalaranna, Patarei Sea Fortress, Hundipea, Bekkeri, Manufaktuuri, Volta, Krull, and other developments mean for Põhja-Tallinn? New developments are good for the entire city, a denser city brings about more shops, services, making them more affordable and substantiating the introduction of new public transportation lines. It is critical to note that waiting in the car queue on Kalaranna, Niine or whichever street signifies non-accomplishments on behalf of the municipality’s traffic planning: there is no more room for cars, as space is finite in every city. When new houses are built and more residents and employees arrive, it does not mean more cars have to appear. A dense, compact city is the kind of city that is highly accessible on foot. It is understandable that the locals be concerned as the living environment shifts. That makes communication all the more important.

Indrek Allmann, ‘At times it seems that Estonians are unequipped to live in the city. You need urban courage. The city is not clogged and will not be full: a city is never finished. It is no problem at all to move about by car in Tallinn, or at Põhja-Tallinn, but it is challenging to get around on foot and by bike. Density, which in other parts of the world is considered a premise for the birth of good urban space, is feared here. Speaking to deaf ears about densifying the city often leaves the impression that we take the past, without acknowledging it, we take the flaws, scale them and project them into a future, get startled, and the result is a scattered, disparate Mumbai.’5

Põhja-Tallinn is not a homogeneous formation. It harbours many smaller centres. The way from Town Hall Square to Hundipea is actually a classic walkable city centre journey. The distance between Noblessner and Bekker Port allows creating many 15-minute walking or cycling centres; all they need is proper, quick public transportation to connect them. This is a matter of broader urban planning. Let us hope a time will come when this topic will be addressed more forcefully.

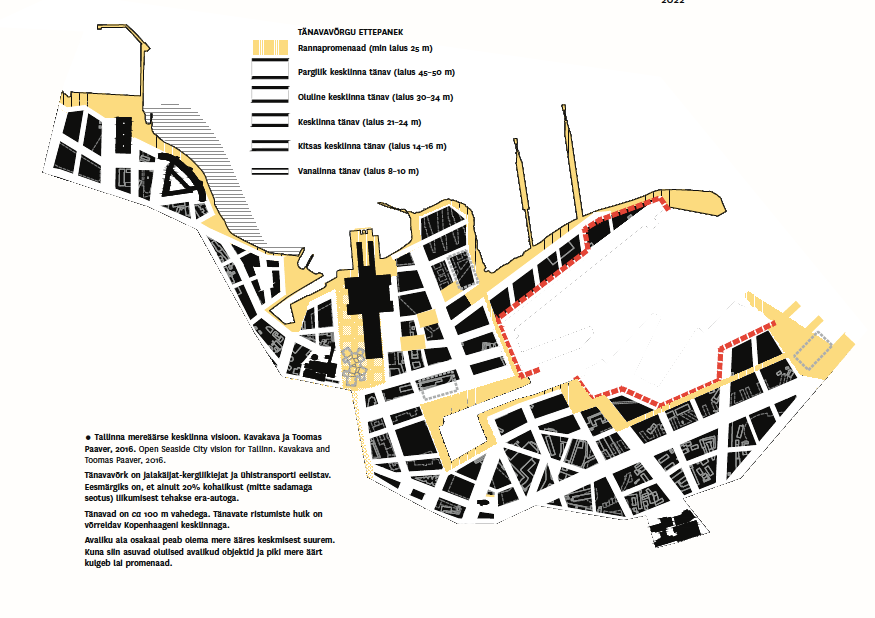

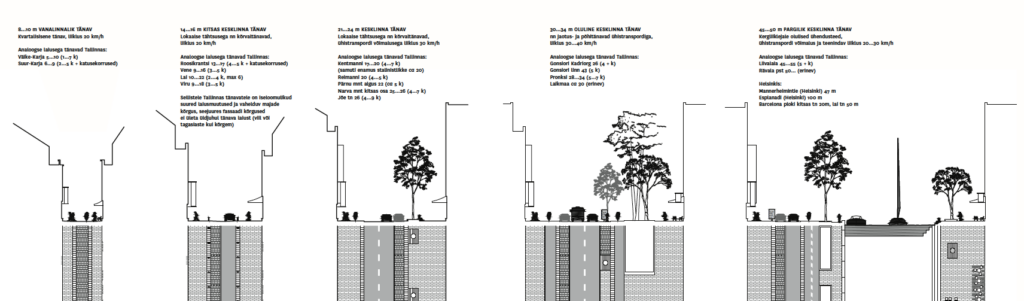

On the Open Seaside City vision for Tallinn

The Open Seaside City vision of Tallinn’s downtown (Siiri Vallner, Indrek Peil, Toomas Paaver, Kristel Niisuke, 2017) prescribes the development of a condensed street network to the sea. It would be a contemporary space from the inside out, human-centred, with streets and parks, a wooden city with natural solutions all the way to the sea. Well-resonating examples would be the Beta promenade (Estonian Urban Lab and Noblessner Port area, 2016) and Environment Building (Kavakava, 2019). It would be naïve to think that Tallinn’s local government would follow the Seaside vision. Could anyone compress the vision into a maximum of two sentences and give a short pitch? If not, then that is always a clear indication of a failed vision in any organisation. For example, the vision states, ‘The space created in the seaside area should in the immediate and farther future have a metropolitan and nature-friendly effect simultaneously, by favouring sustainable modes of transport and mobility, and avoiding motorisation and suburban developments.’6 The city’s strict demand to build 1.5 parking spaces per apartment, with the goal of stuffing 650 cars per 1,000 inhabitants, is not in harmony with this vision or any other vision of Tallinn. In addition to the obvious political response, part of the challenge is resource availability: how many full-time employees should be tasked to implement the Seaside vision?

The future is within reach. Will Tallinn receive a new Noblessner or another random car park by the sea, this we will be able to see in the neighbourhood around Logi Street, situated next to Tallinn City Hall and the Old City Harbour. An expertise carried out by the Estonian Association of Architects in late 2021 concluded that it is advisable to discard implementation of the detail plans for the area. In short, the plans are not in agreement with practically any urban development plan, including Tallinn 2035. The city has an extraordinary opportunity to showcase visionary thought here: the area should be compact, human-centred, and considering the location of the heart of the city, the Põhjaväil or North Motorway, and the asphalt sea of the Old City Harbour, the area does not need parking spaces according to the city’s unreasonable rigid norm. In addition to commercial and living spaces, the City of Tallinn should build urban rental spaces or demand 25% urban rental flats in the detail plans like Copenhagen has done to combat segregation. The goal of the Seaside vision is, ‘The seaside area favours the development of a socially versatile living environment, with populations from various demographics of wealth and age.’7

Põhja-Tallinn is developing, and this is good news for all the local residents: the neighbourhood is becoming livelier. The city in (Põhja-)Tallinn should be made denser. Tallinn’s municipality can encourage itself by ordering a study8 on the example of the Gothenburg and The West Sweden Chamber of Commerce on how much purchasing power increases if urban space is densified in a certain area. Development strategies and visions such as Tallinn 2035, the Seaside vision, and the bicycle strategy must be followed. The parking norm must be updated; the city must not demand 1.5, not even just 1 parking space per apartment, especially at Põhja-Tallinn. In truth, if the city constructed less motorways in a city that is already unproportionally biased towards car traffic and replaced those initiatives with concepts of streets as wholes, building narrower roads for cars that still meet the official criteria—that city would save time and money for itself, enterprises, and people. My best wishes go to the people at the Urban Planning Department and the Tallinn Strategic Management Office. We must, as usual, hold our breath when looking towards the bosses of the city. Or as we would do when winter swimming at Noblessner—stay calm and focus on controlling our breath.

Thanks for the interviews:

Ann Virkus (BLRT Grupp), Indrek Allmann (architecture office Pluss), Toomas Paaver (Linnalahendused) Indrek Peil (Kavakava), Endrik Mänd (the last head architect of the City of Tallinn), Peeter Pere (board member of the Estonian Association of Architects), and others.

PÄRTEL-PEETER PERE is Senior Advisor of Urban Affairs at the Helsinki-based consultancy Miltton Group. He has worked in Brussels and Stockholm and cycles throughout the year ever since. Pärtel is the Bicycle Mayor of Tallinn, a member of the global network of bicycle mayors founded by the Netherlands-based social enterprise BYCS. Pärtel is the vice-chair of the Reform Party group at Tallinn City Council.

HEADER photo by Martin Dremljuga

PUBLISHED: Maja 108 (spring 2022) with main topic Opening Tallinn to the Sea

1 Jo Adentuji, ‘Living near water can be beneficial to your mental health—here’s how to have more blue spaces in cities’, The Conversation, March 10, 2022, https://theconversation.com/living-near-water-can-be-beneficial-to-your-mental-health-heres-how-to-have-more-blue-spaces-in-cities-150486.

2 Jack Shenker, ‘Revealed: the insidious creep of pseudo-public space in London’, The Guardian, July 24, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/jul/24/revealed-pseudo-public-space-pops-london-investigation-map.

3 Ann Virkus, email correspondence with the author, March 17, 2022.

4 Indrek Allmann, email correspondence with the author, March 15, 2022.

5 Indrek Allmann, email correspondence with the author, March 15, 2022.

6 Toomas Paaver, ‘Decision proposal to approve and implement Tallinn Open Seaside City vision’, March 22, 2017, p. 1.

7 Toomas Paaver, ‘Decision proposal to approve and implement Tallinn Open Seaside City vision’, March 22, 2017, p. 3.

8 Bostäder i framtidens hållbara stadskärna, En studie av handel, kommersiella verksamheter och bostäder i Göteborgs stadskärna. Fastighetsägarna GFR, Citysamverkan i Göteborg, Västsvenska Handelskammaren. June 22, 2021, https://www.vastsvenskahandelskammaren.se/artiklar/rapport-goteborgs-stadskarna-behover-fler-bostader-for-att-overleva-pa-sikt-2021/.