In conversation with Toomas Paaver

When I gave an interview1 to Maja five years ago, I came, among other things, to the conclusion that for the creation of great spaces we need more creative officials in the public sector. I’m happy to see that your work is the embodiment of that vision. You work as a creative official in the best sense of the word and a creator of space, you try to understand all stakeholders, you have a good command of strategic thinking and can provide spatial solutions. Could you please describe the basis of this kind of mindset and practice?

True, if I had not had the opportunity to do creative work, or in other words, if I had not managed to set creative tasks for myself, I would not work in a local government. It all began in my job interview where I negotiated a four-day work week and the right to continue in the private sector on Fridays and weekends. Later on I had to give up my so-called creative Friday, but I still have my practice. Thus, the first thing is to have the right and freedom to work also as an architect, design buildings and envision urban spaces. In addition to keeping your mind fresh, the experience of a practising architect and urban designer is important for a city architect as it allows to see your work in the public sector only as a part of a much larger process. This way you learn to sense the difference between the expectations of the public and society and the private owner. In my opinion, the role of the municipal architects is to balance the pragmatic wishes of the client through their opinion or the conditions of the comprehensive plan and this way enhance the architect’s possibilities for designing high-quality solutions.

I have a similar experience. Even if you don’t design, you at least need to analyse spatial solutions and this takes time. When your spirit is numb, also your work as an official will suffer.

Once you have received comments yourself, you will also make comments much more carefully. I try to understand the other party’s interests when preparing conditions for plans and projects and criticising projects. In most cases, there are diverse ways of achieving these interests and recognising them often requires you to dig deeper into the solutions and sometimes also consider them graphically. Similarly, when preparing plans or strategic documents, you need to perceive and trust the possibilities of architecture and also see the possible negative side effects of the well-intended conditions.

Andres Alver has aptly said that in the architectural sense, 90% of urban design solutions fail for one reason or another, and only 10% are successful if all the circumstances are right. There are simply so many stakeholders. I have tried to notice this theoretical 10% and help it to come to life.

In this regard, I have been led by a few principles: to emphasize and facilitate those plans that are less likely to succeed. All pioneering and innovative projects need support to prevent them from getting stuck in the old rut under the pressure of red tape.

The second important principle that I can safely recommend to everybody, especially officials, is the courage to perform some tasks a little poorly and half-heartedly. Taking a philosophical view of innovation and creativity, it is important to allow a break in one’s activities. As a civil servant, your working hours fill up very easily. It is not possible for an official to just sit idly. The way out of this so-called trap of an efficient official lies in one’s courage to be a bit lazy in some things and make an extra effort in some other aspect. It is important to have the courage to distinguish between the essential and the non-essential. There have been no questions about most of the important things that I have achieved as a public sector architect.’

The idea that the work of an architect in the public sector is primarily a clerical job with no room for creativity has not completely disappeared in the society. In my experience, entirely different types of people are suitable for bureaucratic roles, however, the role of a creative architect is still highly important in the public sector. Would you say that urban design and the work of a municipal (public sector) architect is art rather than a technical and bureaucratic work?

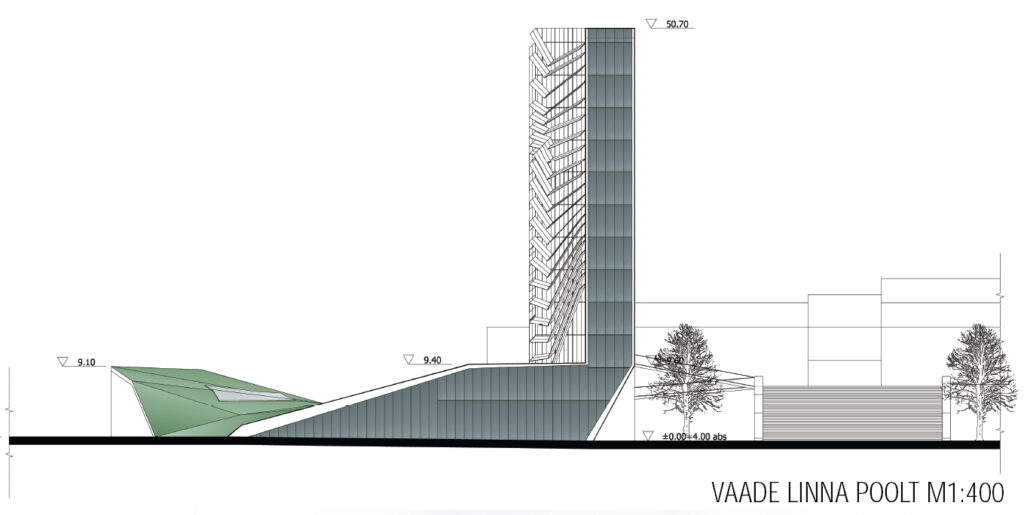

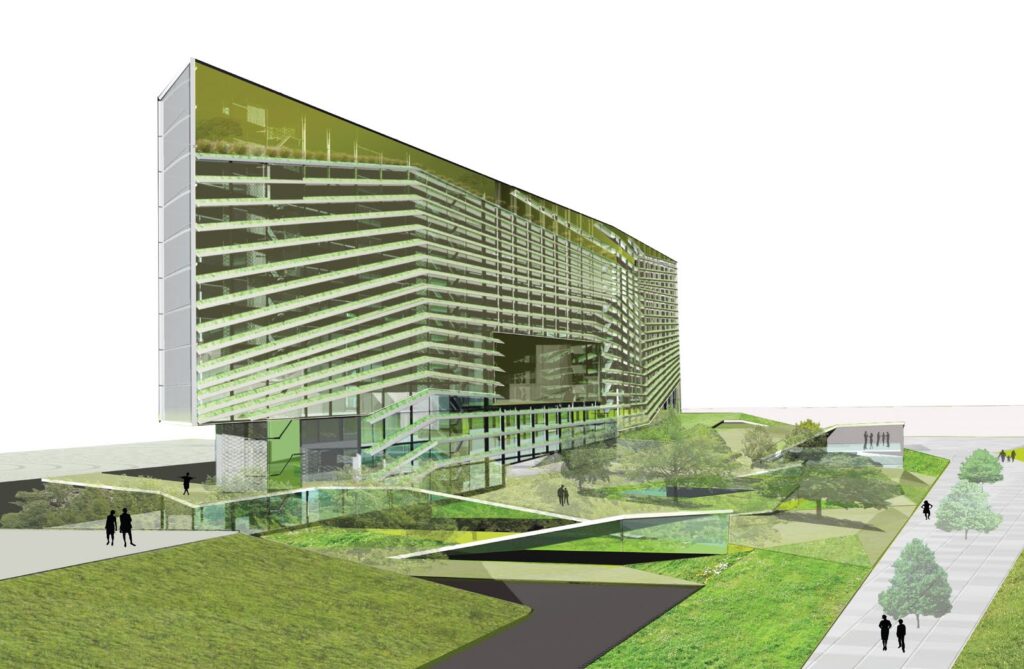

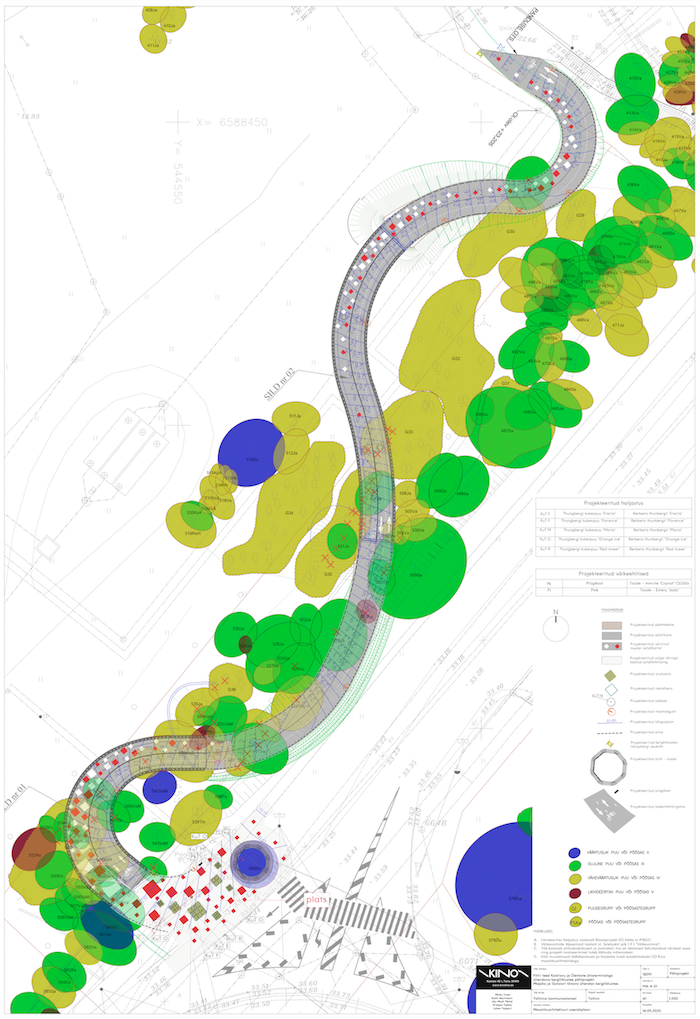

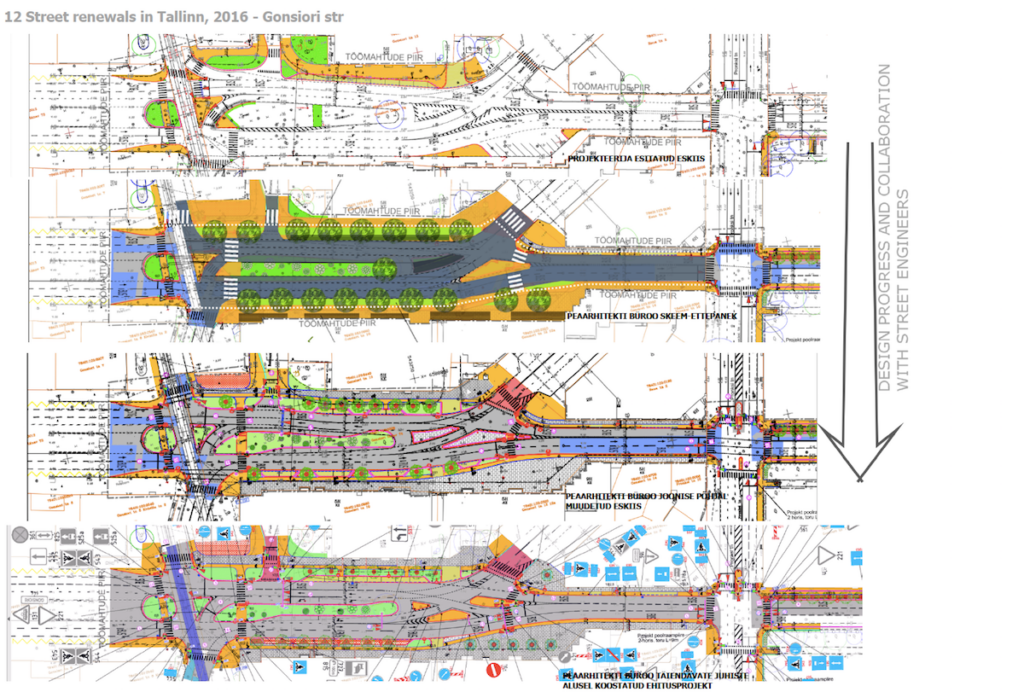

It is art with bureaucratic means! Well, it’s all there, and it largely depends on where you want to go. I have never enjoyed meetings and red tape, I only do it as much as I need to. A large proportion of our work is graphic, we provide solutions on the schematic or sketch level for explanation and exploration of possibilities. The most creative part of our work is preparing briefs and conceptualising tasks, similarly the diplomacy and debates—basically performing arts. We have various motivation meetings for developers and colleagues to reinforce the new mindset. In the spatial design department, we work on very different scales: from citywide strategies and plans to small objects and curb stones.

I have conceptualised the essence of public sector spatial design so that its main object is public space. And not the simplified approach to public space as a separate object but to a space that is inevitable, connects everything and can be used by everybody. If we consider the current and potential public space in every decision and on every scale, also various semi-public and private spaces, including buildings, will acquire a clearer meaning, solution and a place in the spatial structure. Public spaces also allow you to conceptualise the need for regulations as well as freedom.

I’ve noticed that different local governments have a very different approach to public spaces. In my civic activist role, I have encountered local governments where public spaces are considered only from the narrow perspective of ownership. Planning in such local governments does not recognise public spaces outside the plots owned by the municipality. Pursuant to the constitutional principle of the inviolability of private property, the spatial quality of all other plots is liable to the owner’s discretion or benevolence. In my opinion, this approach is fundamentally wrong and in breach of the Planning Act. Besides, we always inhibit the owner’s freedoms by setting restrictions on the size, type and height of the building. When we prepared the comprehensive plan for Haabersti, several landowners asked about the possibility of constructing highrises in totally random locations and considered flight safety height restrictions as the only legitimate building height limit. Looking at single plots, there is really no reason to decline, but as a whole, it is not possible in technical or urban design terms that highrises are allowed on all plots of the entire district. Their mutual interaction and impact on the city would be catastrophic. I would like to say that the value of one plot without the surrounding urban space is non-existent, its value is manifested in the whole.

When I was actively involved in urban design in the Telliskivi society, we truly hoped that at one point the city would take over our activities as that was the whole point of the public sector. We can see that the spatial design unit of Tallinn Strategy Centre has committed to the issue of public spaces and the time of civic activism in spatial design seems to be in decline. But is your work enough for the full development and maintenance of public space?

Our team of 11 is enthusiastic indeed, but we are involved only in some of the spatial decisions of Tallinn, our daily activities are separate from the work of the Urban Planning Department. We cooperate with authorities of various fields—everything connected with public space and the respective design, the spatial solutions of areas and buildings of relevance to urban design, strategies, comprehensive plans and architecture competitions—but we are equal to other authorities and nothing more.

Civic activism is important as it provides a balance to the obvious private interests and makes it somewhat easier for the city to take balanced decisions. Similarly, bringing about changes and achieving spatial quality sometimes requires a supporting or demanding voice. I would like to hear the opinion of the Estonian Association of Architects, the Centre for Architecture or local architecture schools more. Fortunately, the voice of civic activists has reached the political level, that is, high-quality urban spaces and changes are demanded also by political parties.

Last year, we saw an exhibition of your father and one of my teachers Avo-Himm Looveer at Esna Gallery. For some reason, I clearly remember his paintings featuring natural forces dominating built environments. These paintings completed decades ago seemed to be ahead of their time. It all intertwines with the current understanding that nature and ecosystems extend deep into the cities and we should not forget nature in architecture either. Could we say that in future cities, natural networks will become more important than technical networks?

My father actually never taught me, I was intimidated by it and managed to wriggle out of it. But he was a great enthusiast of eco-construction. Already 40 years ago, he attempted to construct a rammed earth wall and experimented with natural solutions. They turned out to be so natural that unfortunately no permanent spaces were actually left. Similarly, nature is equally important to architecture in his paintings with a recurrent theme of architecture becoming a part of nature again. At the time, the destruction of nature and constructing highly urbanised living environments in prefab panel districts were in full swing. Now the society is more worried about the environment on the global scale. Nature is not doing well and we must help biodiversity back into the city as it will benefit also man.

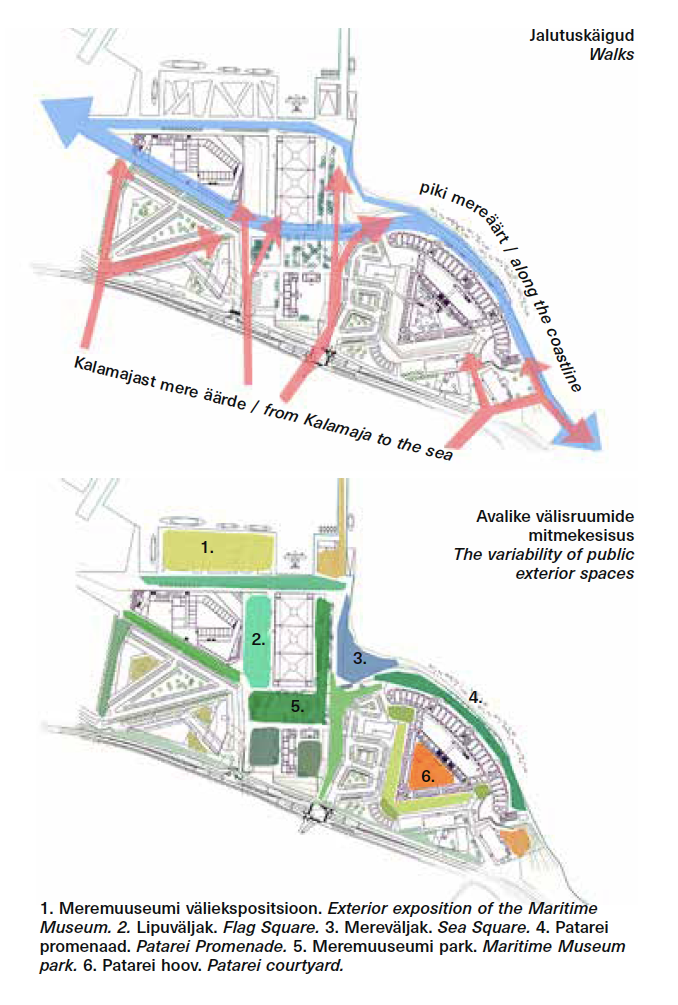

I remember your analysis that there are no seaside parks in the seafront centre of Tallinn, also the seaside section of Kadriorg Park is cut off from the sea, and in this context, Kalarand would have been a great location for such a park. This never happened and perhaps it was meant to be so. I think it is important to make the city denser, however, where there’s a lot of people, there’s also a need for a park. In the increasingly cement-based urban environment, wouldn’t it be reasonable to establish among other things some larger green areas in the growing seaside city centre of Tallinn?

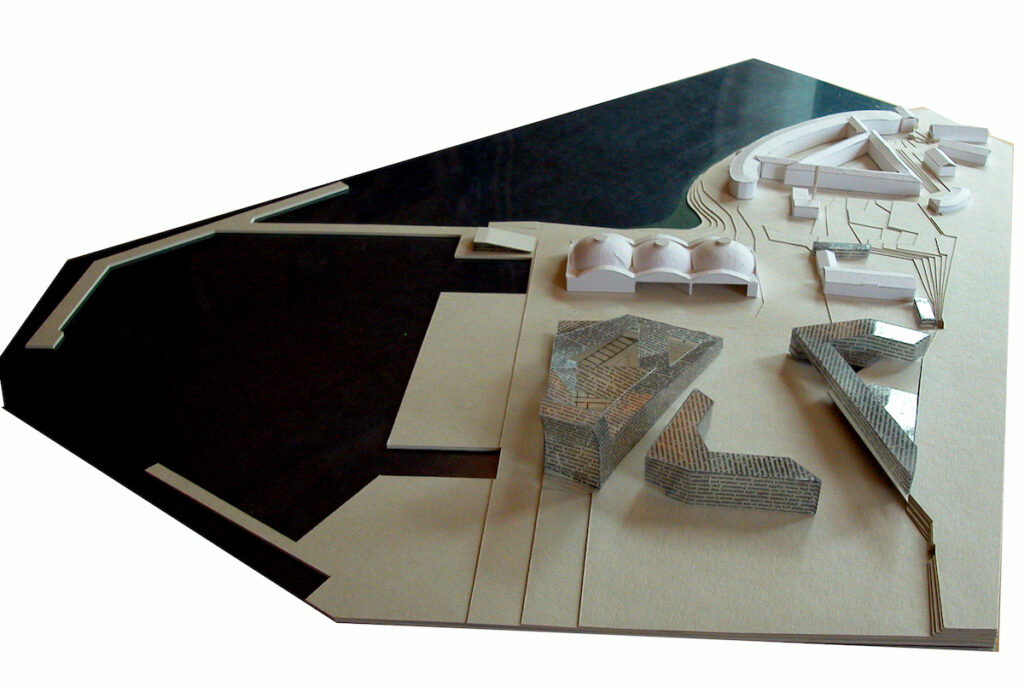

There is still a need for a seaside park in the city centre. The flat coastline joining the sea and the land is particularly important. They managed to retain it in Kalarand. The entry that you and I submitted for the Lennusadam competition actually included a floodable square to highlight the given connection. In addition to green areas, the city centre also needs other outdoor spaces for pedestrians.

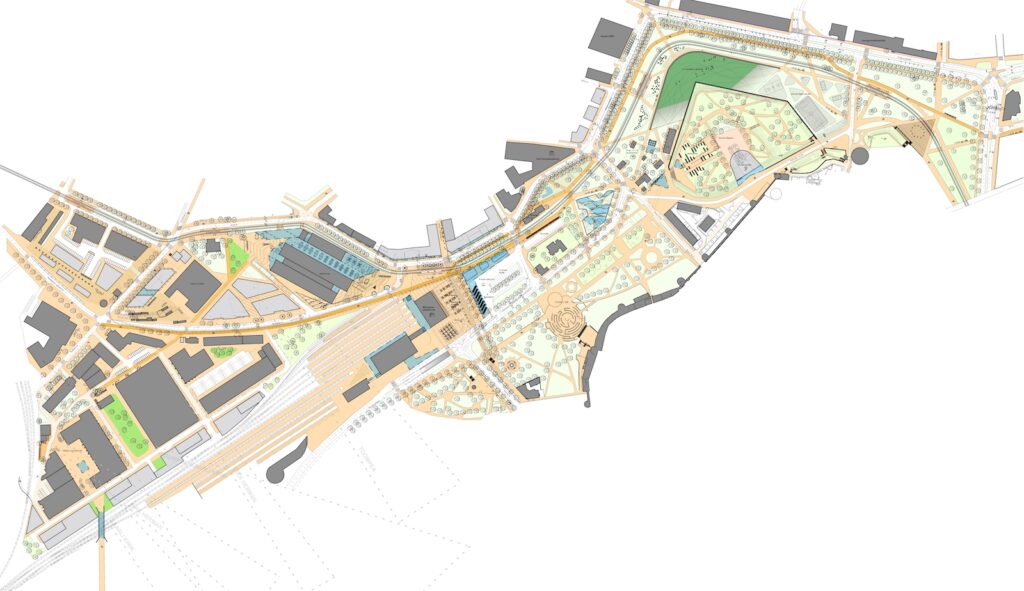

The comprehensive plan prepared for the city centre actually considers the public recreational space more broadly as a green network of parks and avenues. Our aim is to plan a network of socially cohesive public spaces. In addition to the green network, we want to redesign and interconnect into the social space also pedestrian areas, squares, streets and places where something is happening, places with cafés and businesses, places with public buildings or potential for street trading. We could name the Old Town and Rotermann Quarter as parts of the social public space network, similarly the beach promenade featuring very few green areas but at the same time boasting a higher recreational and social value than parks. We will provide the conditions for establishing social meeting places, for instance, in their simplest form of benches and playgrounds in the street. With the given solution, we will meet the major contemporary challenges of urbanised and ageing societies, such as the pandemic of loneliness and obesity.

Kalarand is a magnificent place for swimming right in the heart of the city and it was saved with great difficulty, however, I would like to talk about a more personal problem. I’m in a paradoxical situation—despite justifying a flat beach front that seemed ideal at the time, I can no longer use it in the given form as I need to hold on to something to get to the water. Now I often notice that when I’m faced with obstacles in space due to my irregular movement, it actually does not affect only me. It makes me as an architect see space and the users of space from a broader perspective.

I know that you have been one of the main spokesmen of retaining the beach and swimming area in Kalarand and now you find it difficult to enjoy. If you can use standard solutions, it will never occur to you that the sea and the coast could pose a barrier to some. The solution is actually very simple. We need a handrail to the water depth suitable for swimming. Holding on to the rail, you can get into the water without fearing the uneven sea bottom and waves. I’ve seen a similar solution in Finland and it worked really well. There are quite many people who would benefit from such a simple design solution, for instance, the elderly. We actually have numerous such invisible barriers in the city.

True, and barriers are different for different people. Some find every small step as a barrier, others the scarcity of seating, and eventually the picture of such people is quite varied.

You have been very outspoken about the disruptions created in the urban space by traffic lights. I’m sure many people find this quite difficult to understand. But after some consideration, it could indeed be problematic for some people, for instance, if it is difficult to stop one’s bike or if it takes longer to cross the street, similarly for people with visual impairment. On unregulated pedestrian crossings, pedestrians always have the right of way no matter how long it takes.

A standard pedestrian crossing is a good example, however, making the overall traffic culture safe requires skilful design and deeper knowledge of various users of space. In many countries, it is an understood thing that architects are involved in designing streets. We have encountered it only in some local initiatives while most streets are designed by road engineers much like utility constructions. How could we cleverly combine the roles of an architect and road engineer to make the street network friendly again?

In my opinion, the way engineers and architects think differs in that engineers try to compartmentalise and separate things while architects attempt to combine and merge them. For instance, architects like to suggest shared spaces and combined solutions in the street space, while engineers prefer clear spatial divisions and regulated or grade separated junctions.

You can create safe spaces in either way. The proportion of the role of an architect and road engineer in street design should be similar to designing buildings where good structural engineering is manifested in the indiscernible structures. You can tell a good traffic engineer by the absence of obvious signs of his work: you move intuitively in the desired manner with no excessive traffic signs. The railings, concrete pigeons and barriers common in Estonia as well as the abundance of road signs primarily speak of poor spatial quality. Most of the streets and small roads should be purely about artistic creation as the role of traffic engineering is so small compared to the rest of the spatial design. Also the design of major streets with greater spatial value and carrying the local identity should begin with architectural design, mapping the needs and functions, ideally with an architecture competition. Obviously, it does not play down the role of engineers! Then again, I haven’t heard much that engineers are commissioned to design houses, so perhaps it shouldn’t be the case with streets either.

I keep noticing a recurrent trend in the development of the city traffic, primarily due to the fact that I’m forced to use taxis now. I see the utter neglect of car-users, as many roads are built only for vehicles despite the fact that cars are meant for reaching a destination and getting out of the vehicle. I was acutely aware of it recently along Reidi Road as I discovered that it is quite impossible to get to the seaside promenade as it is not allowed to stop there.

Allowing cars to stop in the street is generally, of course, necessary. The lack of it is indeed yet another invisible barrier. Our spatial design team is actually developing solutions for narrow streets. We try to find effective solutions that would be more space-saving than the standard ones and agree on them with other municipal authorities. We start from the actual dimensions of the objects and the non-standard situations in real life. We design two-way streets of the width of one lane to retain spaces for stopping and parking as well as one-metre lay-bys for taxis, couriers etc.

On a wider scale: a few years ago, we managed to agree on the principles of nine street types of Tallinn. If streets had earlier been categorised only into arterial roads, link and local streets according to the volume and nature of their motorised traffic, then the new classification was added a location value scale, in other words, the criterion of spatial quality. So, now we are working on introducing the location value qualities into the street space solutions.

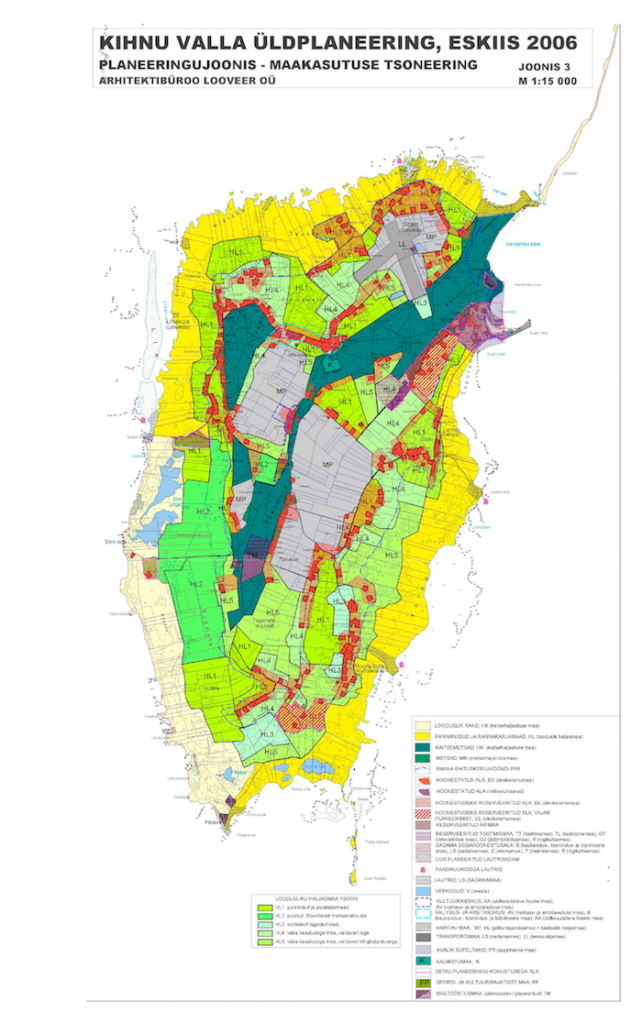

There was a time when I worked as a city architect in Kuressaare and you for the local municipality of Kihnu. Many of us worked for local governments and we have been called the class of municipal architects. I remember the time as a period of fruitful discussions, particularly how you talked about the liberal attitude to construction taken on Kihnu Island. Now you have worked in Tallinn for some time. Is there anything Tallinn could learn from Kihnu?

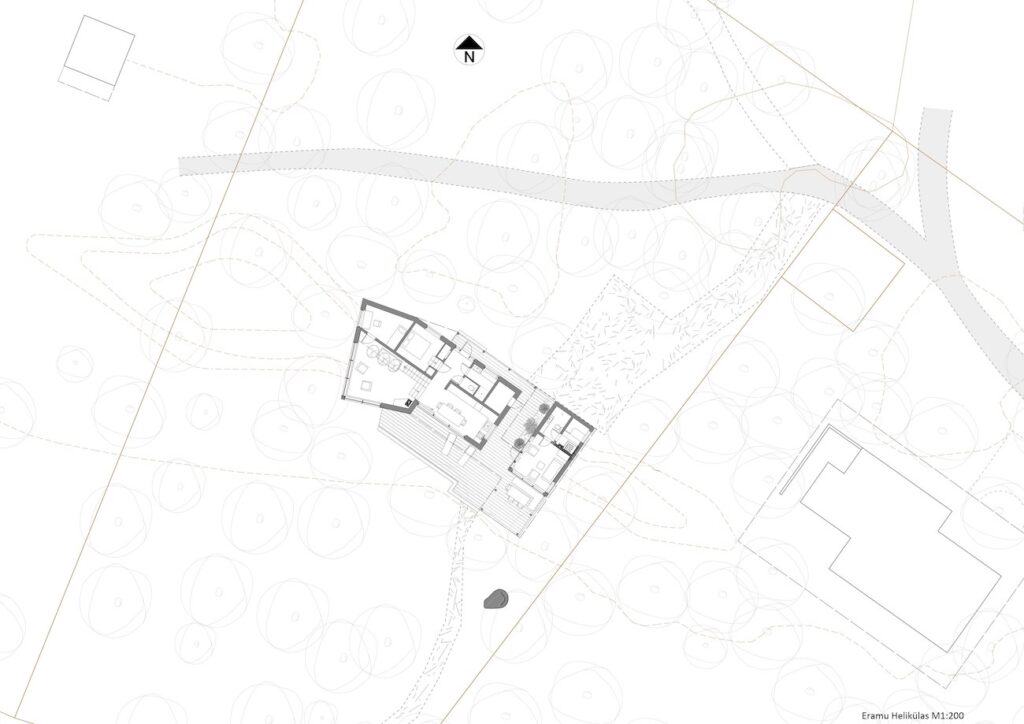

I began working as a town architect on Kihnu Island right after graduation and haven’t regretted it. I could think about several important topics. For instance, they taught me how to interfere as little as possible in construction with bureaucracy. At the same time, it was expected that the village ambience would support their image of spectacular handicraft and heritage culture. The villages and houses on Kihnu are indeed awesome, however, there aren’t many buildings with classic heritage features. Houses evolve with people there: external walls are used as pegs or storage and there’s a seating area below the eaves. It was my task to formulate general planning principles on the number and location of buildings along the village road that would allow free and sustainable construction while also ensuring the conservation of the village ambience in situations where buildings are constructed entirely of profiled sheets. In principle, building sheds out of profiled sheet metal is in keeping with the local traditions as sheds on Kihnu Island were built from basic materials at hand. We couldn’t stop that. The local ambience mostly relies on the community and intervention is required only when aligning the construction activity of summer residents and outsiders as well as the new typologies. Most Estonians tend to live in the same way, perhaps this knowledge is valuable also in Tallinn?

On the one hand, it leads us to the need to understand various users of space and the importance of creative freedom, on the other hand, there’s a growing belief that good living environments should somehow be measurable, computable, programmable. Can these goals match at all?

I like the lyrics by Villu Tamme saying, “Equality is not the same for everybody, equality is to each their own.” This simple statement on the importance of free choice never reaches our laws and regulations. A lot of simplifications and generalisations should be made in regulations and data systems. Such simplifying rules are included, for instance, in the regulation “Requirements for Residential Premises”, the standard for city streets and many plans. The aim is noble: to avoid abnormalities, however, it results in monotonous living environments. I understand there needs to be a uniform scale but it shouldn’t become a universal law.

What is the future of urban design? Can you foresee issues that we are not aware of right now but we should keep in mind?

The world is changing rapidly but cities last for centuries. It seems to me that urban design is too much concerned with reacting to current problems. On the one hand, the rapid changes require flexible curation rather than strict planning, then again, urban design and shaping urban spaces should be based on at least a hundred-year perspective. To fully understand the extent of the possible changes in such a time frame, we may look to history. Everything was different a hundred years ago: the way we move around, the number of residents, economic and educational systems, households, lifestyle etc—everything has changed. I’m sure that urban life will undergo equally radical changes in the next century. Perhaps we shouldn’t focus on all the things that change rapidly. Perhaps we should turn back to pure architectural urban planning: to the design of streets, squares and parks as well as the typical proportions of buildings and courtyards and networks.

This idea can perhaps be summarized as follows: the sensible path for urban planning seems to be to go back to its roots. For example, cars and horse-drawn carriages are similar in terms of size and function. The form and technology tend to change but the spatial relations will probably remain the same also in the future.

TOOMAS PAAVER is an architect.

HEADER photo by Paul Kuimet

PUBLISHED: Maja 111 (winter 2023) with main topic Street Unrest

1 Kaja Pae’s interview with the head of the leader of the Spatial Design Expert Group Jaak-Adam Looveer, Maja 91 (autumn 2017).