TAKLANDSKAPET (The Roof Top Landscape)

Address: Sveavägen 44, Stockholm

Landscape: Johan Paju, Fojab architekter

Building: Gert Wingardh

Completed: 2015/2016

Roof Top Area: 3500m2

A rooftop landscape in Stockholm is a case study to create natural biotope in urban public space for people to use it and gain a year-round experience of the city’s nature.

In recent years I have worked on trying to realize the idea of a natural public urban space that can change over time. I got the opportunity to shape the development of a roof-top project in central Stockholm, when an entire block was developed into a modern office complex by Skandia Real Estate Company. It became possible to test an urban social habitat complex in reality.

Landscape design began with a thorough analysis where we captured the Stockholm skyline to mark the landmarks and landforms. We came to understand its context in the large scale and see the deep structure that influences the spatiality. It all starts with reading the landscape.

Learning from natural biotopes

The rooftop level at 44 Sveavägen in Stockholm is situated high and exposed by the foot of Brunkebergsåsen. The local climate conditions are crucial both for the vegetation and for the use of the site. We learned from the site how to follow nature’s conditions. Which parameters are essential and how can we measure the impact? By looking at similar sites in nature in terms of climate, soil and possible plant communities (biotopes), I found that they are naturally adapted to these conditions. I studied south-facing slopes in the Swedish Alpine mountain areas where resistant vegetation establishes itself in rocky dry conditions.

As I wanted to create spatial units with vegetation, I had to find various biotopes that can work for the design idea. The habitats making up the foundation of this project are the creeping flora found in the outer archipelago that stands up to extreme drought and minimal soil. Furthermore, I used the limestone meadow flora that naturally occurs on the large islands, Öland and Gotland, off Sweden’s coast. These are characterised by abundant flowering and vast richness in species, while also extremely resistant to drought. As I also needed taller woody vegetation, I turned my gaze to the South of Sweden’s coastal scrubland (”Krattskog”) marked by hedgerow species and low wind-pruned oaks. Here the volume effect will develop over time with the thicket increasing in volume.

The positive effect achieved as a bonus when one plays with live nature biotopes is that the landscape is not arranged but invites spontaneous use and own initiative. It is inviting and permissive, not strictly formal. The management is also minimal over the year, basically shaping the landscape by mowing in late summer.

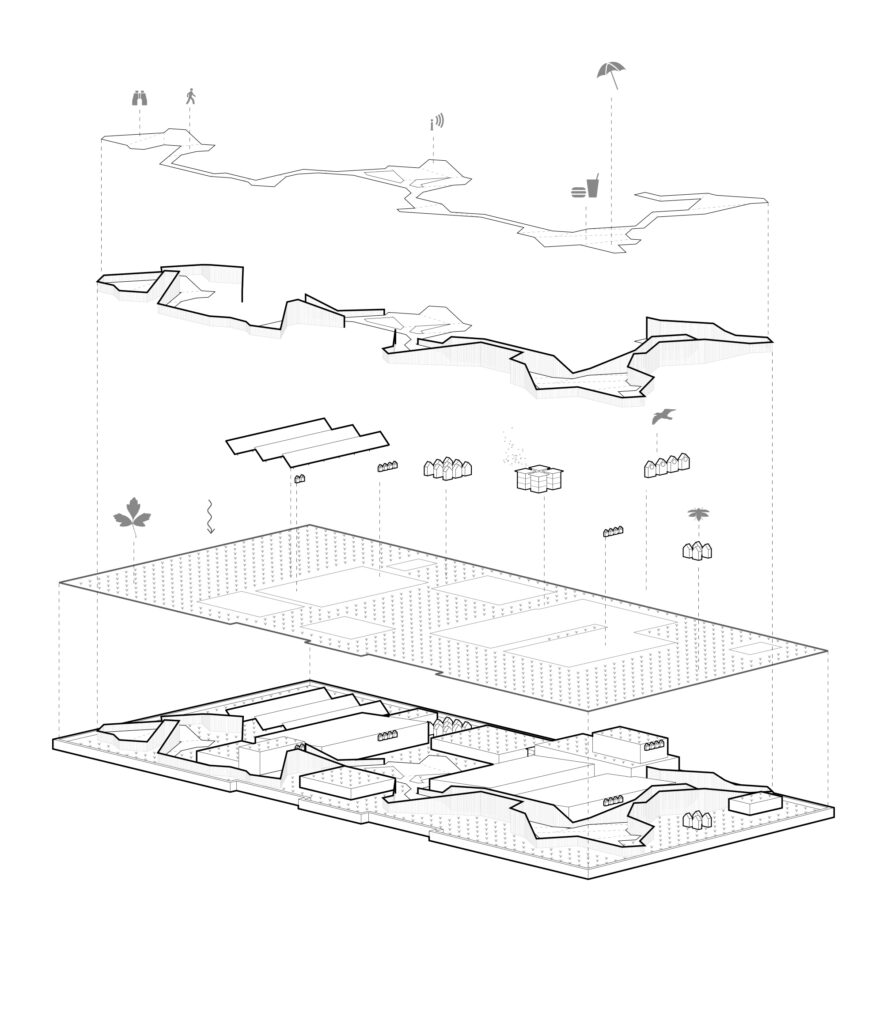

I learned the design of spaces and paths by studying the natural patterns of movement in the subalpine environment where wildlife trails never change direction orthogonal but come from both terrain and the animals’ movement patterns. Based on this principle, we decided to work with angles of 120 degrees when places and string were weaved into the facility. It became the shape or the fractal that the design was built upon. The various sites of the rooftop formed after the seasons and wind direction. There were sunny leeward places as well as cool shades in the summer. It forms the basis for the use and the conditions for a welcoming stay.

The vertical wall elements of wooden slats got their shape and distribution after a study of the surrounding roof landscape. They can be compared to how roof landscape varies in form and distribution, while the structure and material choice aim to do several things at the same time in different scales. The vertical structure is an efficient windbreaker and no turbulence occurs due to the permeable walls. When seen from the side, the elements lead the gaze in the direction of movement; a massive wall is experienced in abbreviation. However, when looking straight at the section, it seems transparent for the most part thanks to its slender silhouette and sparsity.

The floating wooden piers for movement also reinforce the experience of nature as a bottom and base of the composition. A current flow is experienced as continuity. We also use the layer to handle storm water and store rainwater for drier periods.

This project is an example of how to apply landscape thinking to a situation in different scales, everything from the location in the cityscape to finding role models in nature for habitat construction. It is a project that is based on the integration of entire natural habitats with large urban spaces for people to use.

The design of the project advanced a basic idea that with simple means evolution can continue over time. The study of the natural patterns of movement has provided the foundation for the shape of spaces and movements. The fractal patterns move in all scales of the site and are present in the form of a principle one can develop and build on. It can be changed in one year or 100 years. The principle of the project is the same – the horizontal stratification in nature and social layers, as well as the vertical space principle in vegetation and wall elements. Together, the components making up the structure are simple but provide the tools for a complex content. Each input element has several purposes; they build complexity in their meetings and locations.

Finally, the project is all about the concept ”Love Life” whether you mean the biosphere as a whole or as an experience of a designed space for meeting. If it is the architect’s goal, all choices should be weighed against reinforcing purposes. The goal of this project was to bring together an urban nature along with social programs. It has been proven to work, as many people come here all year round to experience the city’s nature. You can have either a meeting with friends and colleagues or a moment of rest in a natural environment in the heart of the city.

Landscape thinking is contributing, not consuming

Which of these aspects could be applied in similar projects? How can you use the knowledge in zooming in and out as well as braiding the context dependency chains? I think we can find the landscape thinking in architecture by focusing on the local on-going processes and resources. The landscape is an on-going process of constant flux. We must travel with it to understand it. We must shape our architecture with it if we want it to interact with all scales. Therefore, we start projects but do not close them. We start them for a possible change and curate them for a set of directions. It allows us to adjust it and let others interact along the life of the project.

Today we are very disconnected from nature with no understanding of the origin of objects and resources. We must ensure that we reconnect links to nature and landscape. We need to understand that we reap what we sow. When you see the beauty of the relationships that allows you to find your position and make you feel important – this gives life its meaning. This approach provides the attitude of contribution rather than consumption. We have wasted resources and broken landscapes and habitats long enough, thus leading to the extinction of several species.

I see that we are beginning to reconnect with the understanding of how things fit together. Interest in and awareness of the loops and synergies are gradually rediscovered. There is interaction between the urban and rural, and nature and culture are once again connected. This principle today is called ”landscape urbanism”, building and thinking in terms of landscapes, thus providing the foundation and feedback to our new architecture. The basic principle is formed of the understanding of the course of events, connections and scales. When you see the patternscapes, there is hope of understanding.

The different local landscapes in the Nordic countries are highly important to me in understanding how to build entire biotopes integrated with process and habitat. Studying them and creating a design tool based on the different aspects of nature’s pattern constitute one of my main interests. The goal in all of my projects is to take care of the entire chain and create landscapes in the city that are a part of the whole, with no maintenance-intense splendour of gardens. I’m thinking more in terms of a farmer valuing closeness and connection to nature in which chains of events and resources interplay with generations of use. To farm is to nurture. Cycles and harvest provide continuity. I want to trigger urban developments where we link processes together in all scales. We need to learn to farm the urban landscape in a similar way. It gives human ties and understanding. The city streets will again become meeting places and rich biological environments where the transport of cars will play a secondary role. The city becomes a stage for life and processes. A living natural city – as it has always been intended. So start – ”Read the Landscape, Follow Nature, Love Life!”

JOHAN PAJU is a landscape architect based in Stockholm, Sweden. He is currently also teaching at the Estonian Academy of Arts in Tallinn.

PUBLISHED in Maja’s 2018 spring edition (No 93).

HEADER photo by Urban Orzolek.