Johan Tali (1986) is an Estonian architect and curator. He received his master’s degree in architecture from Hani Rashid’s master class at the University of Applied Arts Vienna in 2012. Before that, he studied architecture and urban planning in the Estonian Academy of Arts. Since 2016, he has been a doctoral student in the architecture and urban planning department there. His research concerns exhibiting and interpreting various environments as public spaces.

Johan Tali’s career as an architect began in Vienna, where he worked at Soma Architecture (2010-2012) and later (2013-2013) at Wolfgang Tschapeller ZT GmbH. In 2017, Tali moved to Berlin to work as an installation architect at the studio of architect and artist Tomás Saraceno, and later (in 2015) at Graft Architects. In the same period, together with Siim Tuksam, Karli Luik and Sille Pihlak, he participated in several architecture competitions in Estonia. In 2017, Tali and Karli Luik founded Molumba, whose main creative output has been participating in public architecture competitions.

In addition to his work as an architect, Tali has represented Estonia at the Venice Bienalle of Architecture with the expositions ‘Interspace’ (2014) and ‘The Baltic Pavilion’ (2016). He has given lectures on his work in Helsinki, London, Riga, Vilnius, Barcelona, Venice and Tallinn. He is a member of MAJA’s editorial board, belongs to the core group of the Estonian Academy of Arts’ urban development research project ‘Unfinished City’, and co-curates the academy’s public lecture series together with Sille Pihlak.

Johan Tali is the winner of the 2021 Young Architect Award from the Estonian Association of Architects. He earned this distinction for his wide-ranging activities as an architect, curator, lecturer and populariser of architectural topics. Tali co-founded the architectural office Molumba whose works are characterised by a comprehensive and creative spatial approach with a special emphasis on the public space surrounding the buildings. Indeed, the main focus of Tali’s architectural thinking lies in public space and related topics in urban planning. He engages in these topics not merely on a philosophical level, re-interpreting the conditions of human sociality and interaction in an increasingly urbanised world, but also in a more practical sense, by mapping out the future perspectives of Tallinn and the ensuing opportunities for opening and re-interpreting its urban space. Our conversation with Johan Tali suggests a strong underlying conviction that the architect has an important broader social role to play.

A selection of built objects by Molumba

2021 Hiiumaa Sports Centre

2021 Kuressaare Day Centre hall annex

2021 Narva Lidl

2020 Municipal Building in Saue

A selection of competition wins

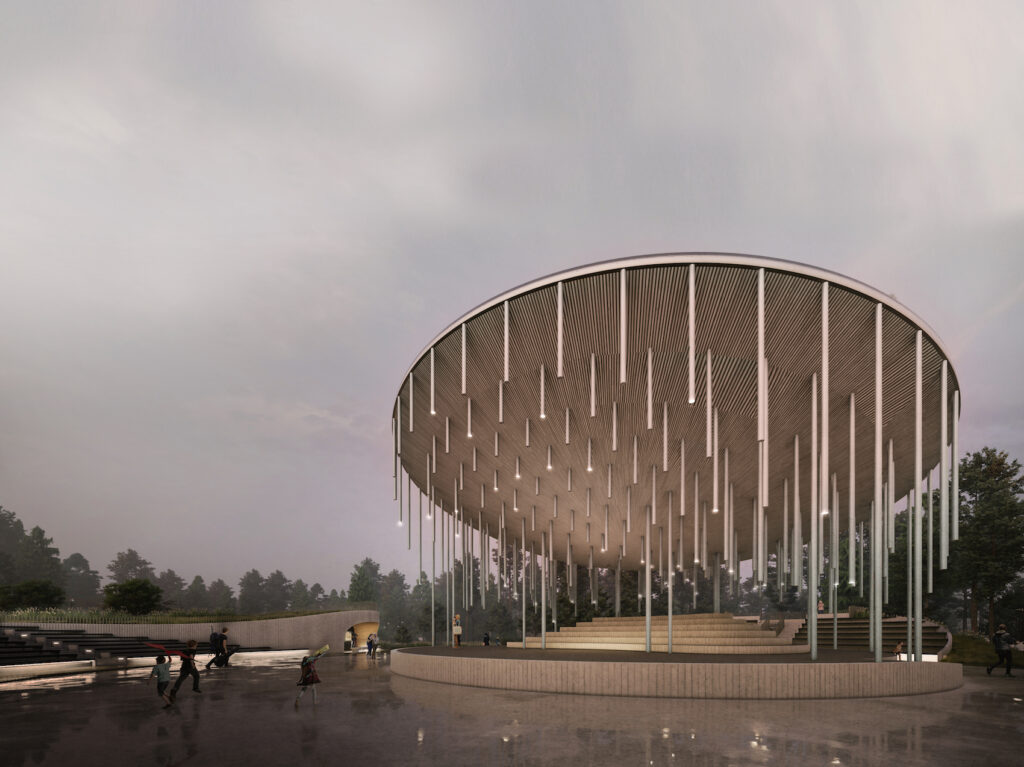

2021 Sindi Rapids Centre

2020 Kuressaare Day Centre hall

2020 Reconstruction of the festival grounds and stage in Keila (with Martin Allik and Häli-Ann Tooms)

2021 Manufactory Quarter (new residential building and site plan)

2020 Mõdriku Learning Centre and Dormitory

2020 Mustjala Day Centre and Boarding House

2018 Hiiumaa Sports Centre

2018 Rääma Rowing Centre

2017 Narva Lidl

2017 Municipal Building in Saue

2017 Reconstruction of Kalevi Central Stadium (with Martin McLean)

A selection of awards and accolades

2021 Honourable mention at the Wooden Building of the Year competition—Kuressaare Day Centre hall

2021 Young Architect Award

2020 Wooden Building of the Year—Municipal Building in Saue

2019 Estonian Landscape Architects’ Union’s Idea Award—‘Baltic Pavilion’ at the Venice Biennale of Architecture

A selection of curated exhibitions

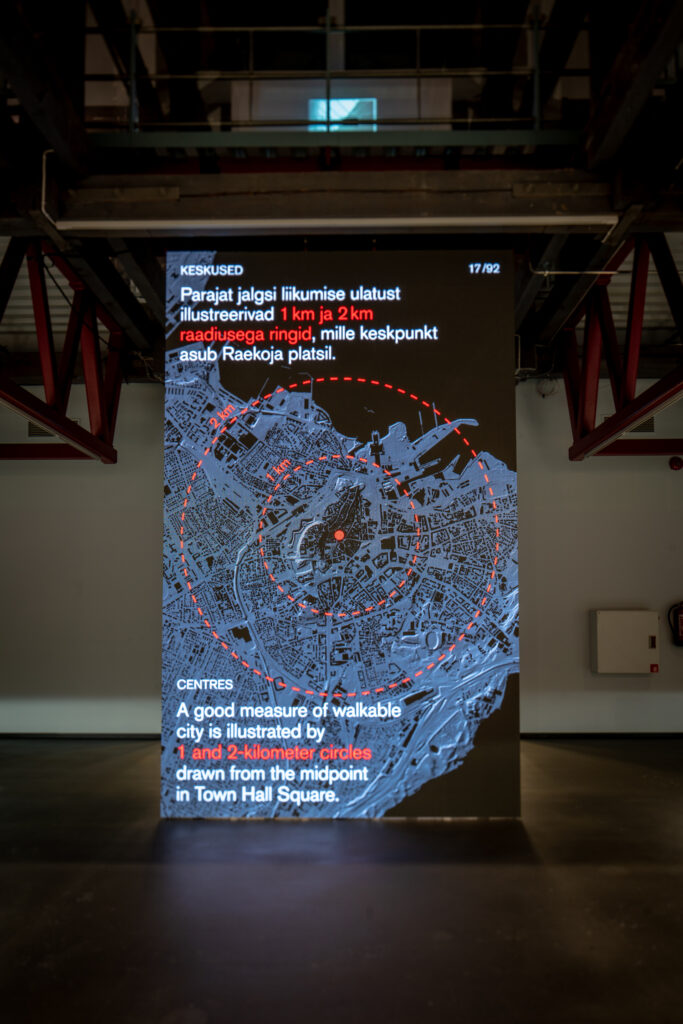

2021 ‘City Unfinished’—exposition at the Estonian Museum of Architecture

2016 ‘The Baltic Pavilion’—Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian joint exposition at the Venice Biennale of Architecture

2014 ‘Interspace’—Estonian exposition at the Venice Biennale of Architecture

A selection of joint exhibitions

2021 ‘The Houses That We Need’—SUPERROHELINE (Molumba and Eik Hermann). Estonian Museum of Architecture

2018 ‘Baltic Material Assemblies’—Linnahall (Molumba). AA School of Architecture, London

Interview by Joonas Hellerma

The world is urbanising. Today, more than half of the world’s population is living in cities, and this share is predicted to rise to 70% by 2050. By that same year, the total population of the world could reach 10 billion. Given our history so far, these are huge numbers. How significant is this outlook for your reflections on urban planning and the associated architecture?

We are living in the Anthropocene—an era where the whole planet is covered by a dense human-made spiderweb of virally spreading urban structure, and at least from the perspective of nature-loving Estonians, this urbanisation can look like the beginning of the end for the humankind. And yet, concentration into cities should also be seen as holding the potential for the survival of humankind as we know it today, and a mediator in adapting to the new circumstances. A city is essentially a tacit communal agreement on how we can cope with our lives better by acting together. If we as humanity will be able to agree on anything at all, the medium of this agreement is going to be the urban environment. As urbanisation continues, our way of life in cities will determine how we live on this planet. Even though cities can have long histories that might make them seem eternal and static, I see each movement and each new layer of theirs as a reaction to the contemporary times. New architecture can only be contemporary. Thus, contemporary architecture always needs to align itself with the contemporary aspirations and tendencies of the society, contemporary knowledge and context. If we want to contend with the crises of our times, we should begin namely with cities—the city could turn out to be an effective crisis operator. Acknowledging the part that human-built environments and humans have played in provoking these crises would already be a good start. We are still only learning to be self-critical.

Looking back at our history, we can see that urbanisation has accelerated significantly, but its harms can be perceived only in a longer run—if only for the fact that building is a process so resource-demanding and sluggish that learned methods and building customs tend to dominate as best practices for several generations. I recently attended a conference where a preceding speaker presented, on the occasion of the anniversary of the architects’ association, the most outstanding achievements of the 20th-century Estonian architecture. The selection included only reinforced concrete structures. A similar selection of 21st-century buildings would definitely be topped by different kinds of building materials, if only for the reason that the use and recycling of mineral resources and raw materials is going to be significantly more important. Building a contemporary city is largely a trial-and-error process, in which we keep looking for spatial implementations of our ideals—implementations that aim to be at least somewhat more adequate than what we currently have.

The global population is growing and this enormous mass of people is concentrated namely in cities. And yet, this does not necessarily mean that these environments would be conducive to human sociality. To the contrary—seclusion, solitude and isolation continue to accompany life in metropolises. This is only amplified by the transition of life into the digital sphere, which you have discussed in your essay ‘Teeskle, et oled üksinda…’ [transl. ’Pretend That You’re Alone…’]. How to plan urban spaces that are required to accommodate many people, but also diffuse the masses? How should we imagine dense districts that nevertheless enable natural, unforced social interactions?

This question comes down to the issue of public communal space! Just like the essay you referred to, which spoke of the individual’s relationship with the collective, it concerns the general question of how all the solitary souls in the city could find their place and their companions. On the other hand, it is also a question of spatial design, of how we perceive the city as individuals, and how we could feel at home there. From an individual’s perspective, a simple example would be to compare urbanisation with changing one’s place of residence. Social interaction is easy when your relationship with a place goes back several generations, but something else altogether when you move to an urban space that is foreign to you—a wholly new kind of environment with a different rhythm of life and different people.

From an architect’s point of view, it is important that public space would be open to what is foreign, and conducive to universal and inventive uses of space. One aspect of unforced sociality is also the possibility to continue in a carefree manner with your way of life and customs, continue being your habitual self in the new place. The threshold for various uses of urban space should always be low. You can tell a good city namely from the opportunities it offers to everyone. I have always been fascinated by how we go about in space, but rather for the reason that the purpose of an architect is to expand that spatial vocabulary, not to refine and concretise any particular patterns of behaviour or practices. If space becomes very specific and heavily coded, its use becomes increasingly homogenous and its users begin to look like a homogenous mass.

Are there any (large) cities in the world that provide good examples of this kind of open and opportunity-laden spatial design?

A good urban space is able to carry the urban life. One surprising example of an opportunity-laden urban space is Barcelona, which—with its Cerdà-drawn plan of uniform perimetrical city blocks, reminiscent of a chequered carpet and rather antiquated by now—looks rather boring, expectable and rigid on map. On the scale of buildings and streets, however, urban planning based on this basic principle enables quite a flexible allocation of diverse forms of life into each single unit (a bird’s-eye view of Barcelona shows only identical square-shaped city blocks). Here, architecture undergoes a scale shift—buildings that make up the block become a universal hyper-building. The cut off corners of blocks form a new spatial situation at the intersections—the latter turn into squares that accommodate cafes, sitting places and greenery, and can be seen as a second living room in an otherwise dense residential environment. Life wants to and is able to move out to the streets. This kind of spatial quality is already in the DNA of each new project at its birth. The life there is structured by the street sides of ground floors.

Jumping now all the way over to the other extreme—it is quite fair to be heavily critical of our own modernist housing districts, where public functions such as shops, entertainment etc. have been hived off from the buildings and concentrated to larger nodes, where you are not likely to get the aforementioned living-room feeling. Free-plan spaces between the buildings are filled with vehicles, for there is a constant need to go somewhere else. In Estonia, new residential districts usually ask for 5% of commercial spaces besides housing—this is the most that Excel allows. I believe that this percentage should be much greater, but in order to get there, we should first look at these projects in a more informed way and try give to sense to living in an urban environment. Developers should also develop models of living. We have tried to observe this logic in designing the Põhjala Quarter, where our aim was to offer everything needed for living, working and leisure 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. We definitely have a gene for this kind of an intertwined life—think of all the business stalls and corner shops that popped up in the suburbia after Estonia regained its independence.

A bird’s-eye view of Estonian cities reveals that many are carrying the burden of Soviet-era housing construction. Khrushchyovkas and apartment blocks in kolkhoz centres remind us of the large volumes of our recent housing and building stock. How much of it should in your view be re-interpreted or maybe even rebuilt in the next few decades? Or are we bound to put up with this heritage for decades to come?

This has always been a very important question. We know of examples from urban history where entire cities have been reinterpreted or overhauled in a project-based manner—think of the bourgeois boulevards of Haussmann’s Paris that replaced the earlier meandering slums, or the subsequent avant-garde urban structures by Yona Friedman that float atop Haussman’s Paris. Cities are constantly changing, but we cannot and should not disavow their history. At the Venice Biennale of Architecture in 2016, we examined such contextually charged spaces with our exposition ‘The Baltic Pavilion’—more precisely, how different influences have given rise to a unique Baltic space. The context in question might involve ideology, economic circumstances, geology, climate, etc.—all these factors combine to influence the built environment. The city is a living system, and just like we are unable to rewind what we experience in life, we cannot rebuild our cities without being in touch with their context and situation. Speaking more specifically of the Estonian spatial culture half a century ago, a certain critical undertone also comes from a negative reaction toward the occupation authorities. The whole Baltic region is full of identical apartment block districts that definitely should have been built in a better way. On the other hand, I would be wary of letting these criticisms inform how we create new architecture, because in its own time, that Soviet housing stock was likewise an effort to renew the existing urban space. Retrospectively, it is easy to say that everything went wrong. Granted, most of it was poorly done. But we need to come to terms with these scars. In creative practice, it often happens that an outdated building has to be replaced with a new one. The question is, what kinds of past qualities are we able to transfer to the new building?

You are a researcher and leader of the research project ‘City Unfinished’, which focuses on contemporary urban planning through the example of Tallinn. Within this framework, you curated an exhibition at the Estonian Museum of Architecture from January to May last year that highlighted many interesting facts and layers of meaning about Tallinn. However, after thirty years of the restoration of independence, we must admit that Tallinn has seen a lot of spontaneous housing and building development rather than urban planning in the classical sense. Saarinen’s project of Greater Tallinn from more than century ago envisioned grand boulevards, public administrative and cultural buildings, but in this respect, Tallinn is still very much unfinished—for instance, we are still lacking an opera and concert hall that would meet the needs of musicians. How could Tallinn make it so that these kinds of urban planning visions would not remain confined in museum archives?

The bulk of our creative work at Molumba, the architecture office we founded with Karli Luik, consists in competitions and projects for public buildings. I see it every day how the Estonian National Symphony Orchestra is looking for a place of its own or how Anu Raud very much needs her own museum. Creating cultural objects is nevertheless premised on actual consumers and managers of culture. As architects, we read the audience rather than the competition brief, and try to create spaces in the city that would be adequate for their activities. We do not need to insert a cultural function to each spontaneous housing and building development in the same way that the Finnish insert bomb shelters to their apartment buildings, but it sure would be good if the people living in the city would be thirstier for culture. In the context of ‘City Unfinished’, we also discussed the culture of urban living, an important part of which is the citizens’ capacity to even desire for good public spaces, including public buildings. In the times of populist governance, voting with one’s feet seems like an increasingly efficient way of attaining the desired kind of urban space. In Estonia, market and policy are still lagging behind people. It is true, however, that the task of enlightening the public should be carried out by architects who are more informed and have a better sense of urban space. Visions such as Saarinen’s Greater Tallinn are indeed one way of conveying directions in which the city could be improved.

The focus of your interest has been creating and designing public spaces in a contemporary city. Why are you fascinated by this?

I have always seen public space as a litmus test of the basic principles and common needs in the society. Besides public space, there is always the private space of individuals, but this seems to me intuitively a territory where the critical decisions are to be made by the individuals themselves, and where the architect is merely the implementer of these private ideas. I am rather collaborative by nature and seek understanding with others. Sometimes I even feel slightly terrified of the idea of designing someone’s home while relying on my own perspective, with all my characteristic quirks and preferences. However, public space tends to get neglected in this sense—after all, someone would need to speak for everyone and do it with such a filigree that no one would feel as if their opinion was not taken into account. Hannah Arendt has written of how those speaking in the public spaces of Ancient Greek poleis spoke as if they were wearing masks, taking on the role of a citizen and performing a certain rite. Public space was like a stage where one could address other citizens. Today, the idea of such a social rite might appear overly elitist and would set the bar for the use of public space too high. Public and private spaces are increasingly intertwined—we have to be able to see behind the masks in the urban space and bring a little bit of our homes to the street. This would make the urban space more expressive of who we, its users, really are.

Are there any general principles to planning and creating buildings that would connect them better with the public space of a city? How much have you tried to experiment in this regard in your work as an architect?

At Molumba, we have observed the simple logic that every building resides to a greater or lesser extent in public space, and, in addition to the operating logic of the building itself, this gives a big role to the design of its immediate outdoors and external appearance, and how it is perceived by the public. We need to anticipate how people will come to use the building and how it could frame a view or set a background. This leads to the idea of the building and landscape merging together to form a new space. We have done this in a quite straightforward manner with the large hills of the municipal building in Saue, with Narva’s Lidl, and maybe most prominently with the Hiiumaa Sports Centre, where the area in front of the main entrance forms a public activity space with playgrounds, skate ramp and sitting areas. Karli joked during the opening of the building that in the context of Hiiumaa, the sports centre is, due to its volume, like a friendly alien that has plowed into the ground and created a new surface form. Jokes aside, this shows a clear ambition of intervening in space and managing it. Often we are also able to express those ideas spatially in a very demonstrative way. For instance, the arches of the municipal building in Saue are hewn into the laconic triangular form of the building and the public space around the building seems as if it has been chewed out from its volume. Roof, entrance, courtyard, wall, opening, intersection of paths—all these archaic architectural elements need to be put to work also outside the building, with every project! Another, an almost elementary effect comes from cardinal directions and daylight. Vitruvius already knew that urban space is shaped by the sun. Nothing has changed in that regard. If we want the building to be surrounded by a good outdoor space, we need to design it so that climate would be conducive to this, and architecture and good planning can help us in this regard. This is often overlooked in buildings and experiencing it takes time, but for us, it is always strategic decision, for all sides of the building cannot be facing towards the south.

Coming back to the example of Tallinn—do you believe that it is possible to create human- and nature-friendly public spaces in Tallinn today? Where should we expect to see changes first?

It would be correct to talk of our ecological footprint, daily mobility needs and footprint of new buildings compared to existing buildings. We should also discuss how we can bring back natural biotic communities and biological diversity to built environments. Good design and thoughtful urban planning actually enable us to do all of that. We could say optimistically that these steps describe a city becoming more sustainable and nature-friendly over time, thus helping to salvage our habitual way of life on this planet. However, personally I find that we first need to achieve a certain camaraderie that would then drive us in our daily lives, but also remind us that we are all in this mess together. I believe that this is acutely true in regard to urban space and invites new forms of cooperation as citizens.

How do you plan to proceed with your ideas? Could the exhibition ‘Tallinn—City Unfinished’ provide a material input that would help Tallinn to develop in the desired direction? In your view, what kinds of changes can we most realistically expect in Tallinn in the next few decades?

‘City Unfinished’ actually began as a research project in the Estonian Academy of Arts. That study led to the exhibition and then to a book—and I can tell you as much that in December, we started filming a seven-part TV show for Estonian Television. The show will be called, once again, ‘Lõpetamata linn’ [transl. ’City Unfinished’]. The topics at hand are difficult to present in a manner that is straightforward and intelligible for everyone, because much about cities is experiential and intuition-based—many things simply happen above our heads, on a larger scale. In order to cultivate the culture of urban living, we need to explain its logic and basic principles to as many as possible. I believe that change begins with the city dwellers themselves and our readiness to ask for better urban spaces at every opportunity. I believe that this will soon amount to giving up our habit of sitting voluntarily in our cars for half a day, increased consumption of the urban space around us and increased attention to developing it, as we come to feel more and more in the middle of it.

JOONAS HELLERMA presents the weekly cultural talk show ‘Plekktrumm’ and is the culture editor at Estonian Public Broadcasting.

HEADER photo by Paul Kuimet, graphic design by Margus Tammik

PUBLISHED: Maja 107 (winter 2022) with main topic Evolution or Revolution?