RANNAMÕISA RITUAL BUILDING

Architect: Reio Avaste

Engineer: Tõnu Peipman

Bespoke Works: VIP Projekt

Commissoned by: Strantum

Construction: Tabasalu Meistrid

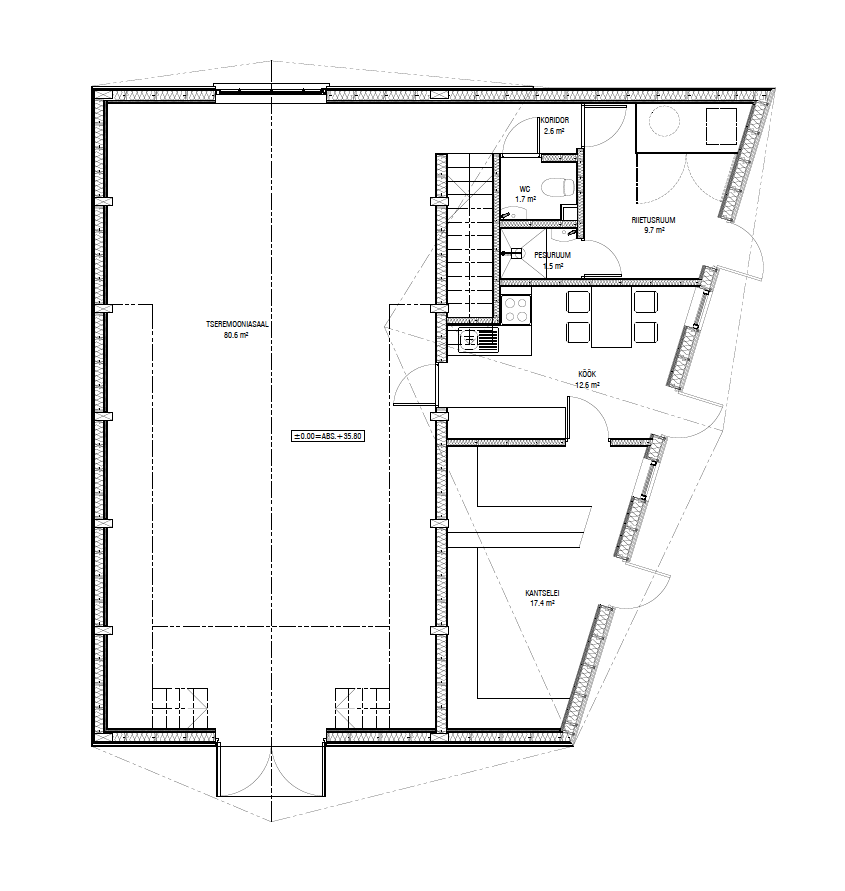

Gross Floor Area: 170,2 m²

Completed: 2017

Rannamõisa funeral home has taken a highly interesting path since its opening. Namely, the opening of the building was accompanied by a change of identity. Guided by the common wish of the management and visitors, in addition to funerals and wakes also other momentous family events such as births, weddings and concerts came to be included in the functions of the building. From birth to death – just as in the church. This was the transformation of the funeral home into a ritual building bearing a somewhat more general name. Was the change of identity brought about by the author through the architecture or the client through the functions of the building? What does this say about our culture of death and the development of the respective architecture?

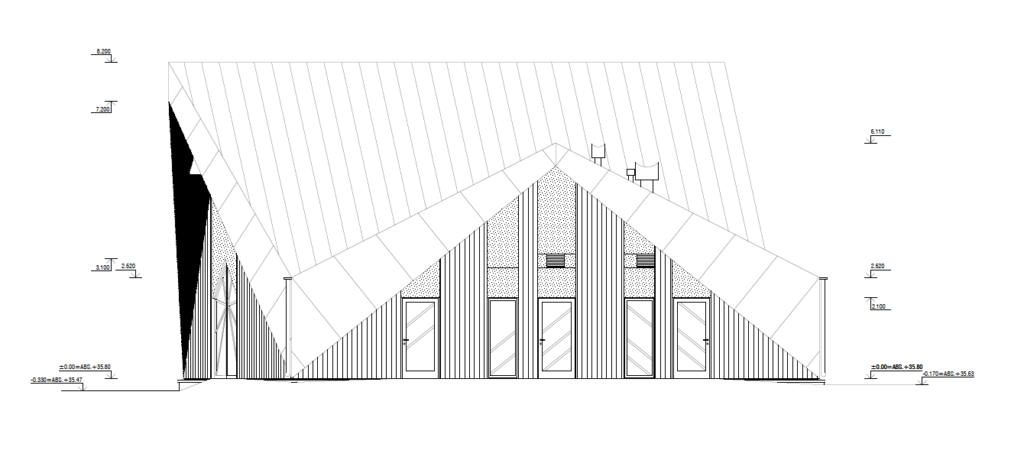

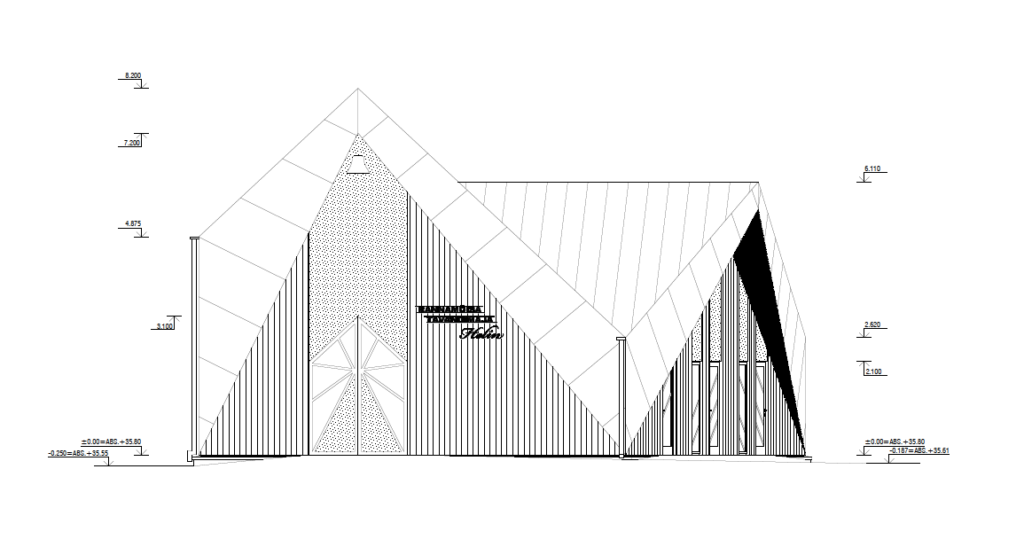

Reio Avaste’s project of Rannamõisa funeral home has reached a curious balance on the line of spontaneity and conservatism. It is an homage to the nearby neogothic Rannamõisa church featuring a play with dramatic forms and acute angles. The building does not seem too defiant, instead, its striking geometry comes across surprisingly unpretentious and down to earth. it features reverence to death while also maintaining the architectural individuality that would set a momentous event such as death apart from the mundane daily life. The given solution is in harmony with the environment and serves its purpose. The modest stone-grey tones prevent the otherwise bold form of the building from becoming a blot on the landscape. The grey tones also match well with the adjacent church, the headstones of the cemetery as well as the nearby road with its passing cars inexorably breaking the silence in the graveyard and reminding of the fast pace of urban life and the tasks to be finished. The appropriateness of the architecture in the surroundings is also one of the reasons for the acknowledgment for a new building fitting into its historic environment presented to the funeral home by the National Heritage Board. Compared to the architect’s earlier similar project, the funeral home in Rakvere, the one in Rannamõisa clearly includes more references to historic architecture.

The need for an annexe to the church emerged as there are few secular funeral homes in Harju County. A non-religious funeral is not spatially related with a church. In broader terms, the secular ceremony and gathering are relatively similar to religious traditions – speeches are made and sometimes also musical performances. With the increasing popularity of secular funerals, there is also a growing need for an alternative to churches. Then again, the number of deaths is increasing in the ageing society, especially in densely populated areas. Although there seems to be no lack of space in Estonia, the preferred burial place is near home. Thus, the most popular cemeteries tend to be in densely populated areas with limited free space. Such phenomena are evident in many urbanised areas, with large cities in the most critical situation. New tidied-up cemeteries and buildings attract also people from nearby areas, for instance, also Rannamõisa funeral home is often visited by people from Õismäe. In addition to its location, also the ease of use and quality play an important role, and the given requirements are certainly met in Rannamõisa.

The initial task for the author of the annexe to Rannamõisa cemetery was to create a funeral home with no additional function. The facilities were primarily meant for funerals and wakes. However, the atmosphere and interior eventually turned out so bright and ambivalent that they were considered suitable also for other events. The interior of the former funeral home and current ritual building is spacious. Entering the empty room, you feel as if you have stepped on the stage and you wish to sidle quietly along the wall to avoid further attention. This may also explain the wish to move away from the funeral home identity. Although the airy room gives consolation and adds a touch of brightness to the event, it also draws attention to the people involved. There is little shelter for the quiet grief common to Estonians. On the one hand, the spaciousness and lightness of the interior act as a normalising force and presumably bring some relief to the gloom of mourning. On the other hand, it provides little consolation and intimacy that many people yearn for at the time of grief.

The funeral home has been in use for over a year now, and the first conclusions can be made. The locals say that the more recent funerals were still held in the church. Then again, the reasons for it do not lie in architecture. It is worth considering that secular funerals often take place in the crematorium followed by the cremation on site. People come to the cemetery only to bury the urn and by that time, the larger gatherings have usually already taken place. Religious funerals, on the other hand, can take place near the cemetery. Thus, the need for space in the cemetery is more important in case of religious funerals where the Christian tradition of a burial in a coffin is still retained. This leads to a vacuum in the burial home’s function. Although there is an increasing need for facilities for funerals, it is clear that the space for a secular funeral should be more related with a crematorium rather than a cemetery.

This, in turn, mirrors more general trends in the society with considerable changes taking place in the culture of death. Although it seems that urn burials have become a norm in Estonia, there will most probably be substantial changes and further developments of it in the future. Primarily in large cities such as Tokyo, Hong Kong London and Washington, the lack of burial places has reached a critical point accompanied by drastic changes in the burial traditions and the respective architecture. In the given places, environmental-friendly burial customs are becoming increasingly popular together with spatial developments appropriate for the new burial methods and traditions. For instance, the competition for the future Arnos Vale Cemetery in Bristol in 2016 was won by the project “Sylvan Constellation” designed by the Death Lab of Columbia University. The project makes use of the energy from the biomass decomposition in producing light which is transformed into the architecture around the cemetery. So far, no future-oriented environmental-friendly projects have been commissioned in Estonia and in the light of the funeral home in Rannamõisa, it seems that we have not perhaps even acknowledged the changes that have taken place in the secular funeral traditions.

It is an award-winning funeral home while the actual value and realised function of the building lie in something considerably more general. What would the architecture have been like, if it had not been designed as a funeral building but as a ritual building? Perhaps many of the possibilities that could have been proposed to a ritual building remained unuttered as the author regarded it primarily as a funeral home. Perhaps various spatial added values could have been proposed already at an earlier stage, for instance, for exhibitions, concerts and various gatherings thus enhancing the potential of the area and the building. All in all, it is the user who defines the importance of the building and passes the final judgement. Although the identity of the funeral home has changed, the building is full of satisfied employees who are happy with their practical work environment and strongly sense the added value that the space provides with no craving for what could have been. However, the challenge remains: what are the contemporary requirements for facilities related with death so that they would be used for the right purpose and retain their importance also in the future?

KAIA TUNGAL is a scenographer and interior architect.

PHOTOS by Reio Avaste

PUBLISHED: Maja 98 (autumn 2019) with main topic Author