MÄETAGUSE SCHOOL AND SPORTS AREA

Landscape architecture: Liina Einla, Edgar Kaare, Terje Ong ja Timo Saabas (TajuRuum OÜ)

Commissioned by: Mäetaguse municipality

Constructed by: Kivipartner OÜ

Surface area: 1,5 ha (exludeing the back and front square of the park)

Project: 2016

Construction: 2017

Known for its openness to change, Mäetaguse borough has successfully combined its central area comprising buildings of various eras and the great outdoor space into an effective and comprehensive environment.

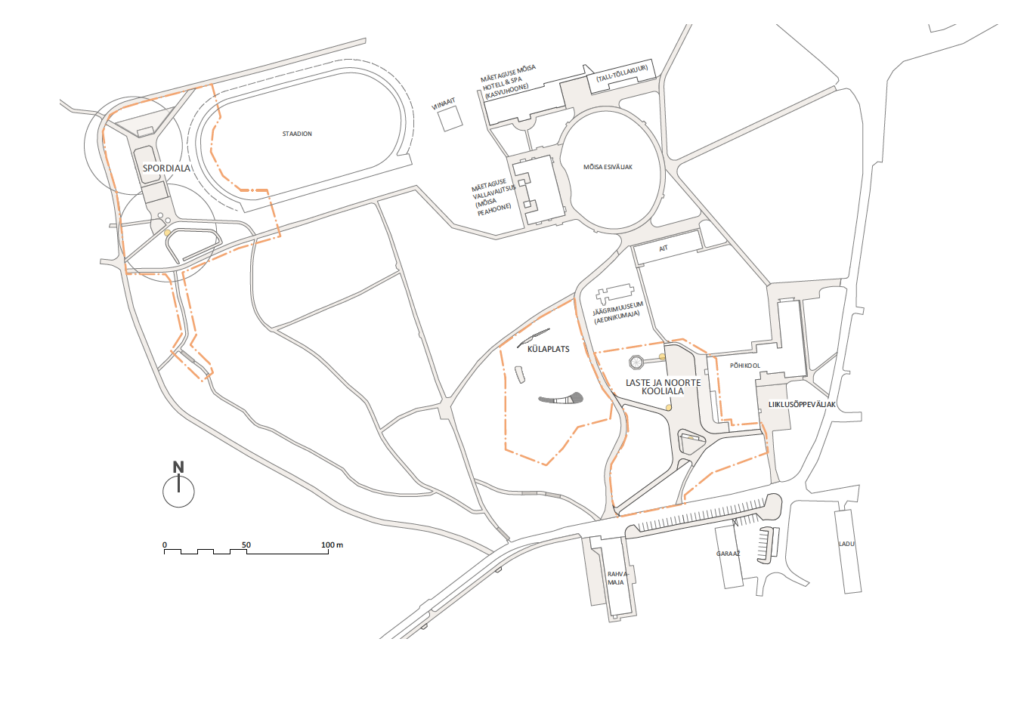

According to Statistics Estonia, the population of the tiny Mäetaguse borough amounts to 512. The heart of the place is the 16th-century manor estate that over the years has evolved, flourished and changed ownership on several occasions, with the Rosen family as its last aristocratic owners. After accommodating a school and flats during the Soviet era, it gradually faded until it was brought to life once again in the early 21st century. The main building now houses the local government offices, there is a hotel and restaurant in the coach house, a bathhouse in the former greenhouse, the school’s handicraft facilities in the large garner and rental premises for events in the smaller garner. The last missing piece was the restored border areas of the manor park including the sports facilities and the school surroundings.

Knowing the state of manor estates in many other places in Estonia as well as the fact that Mäetaguse has not participated in any of the public space programmes or organised public (landscape) architecture competitions while the manor centre nevertheless received the annual landscape architecture award last year for the work by landscape architecture office Tajuruum, it all seemed rather astonishing. I was intrigued by this special place and the people behind the changes. So, on a dim December day, I went to check out the place.

The heart of the manor complex seemed charming and dreamlike even on a gloomy and grey December day. In the given season, the Neo-Classicist buildings painted in light colours form a particularly strong contrast to the dark landscape and the bare sombre park. Together with the school, the compact manor estate is clearly distinct from the rest of the borough that mainly includes the industrial and agricultural buildings from the collective farm era, prefab panel buildings with a few detached houses farther in the distance. The reconstruction of the central part of the manor park and the front square of the main building was designed by Artes Terrae while the park elements together with the school and sports area are done by Tajuruum landscape architects. I first had a discussion with the head of the local municipality Tauno Võhmar and then inquired about the landscape projects from the environmental specialist Martin Miller.

Originally from Ida-Viru County, Tauno Võhmar grew up in Toila but his grandparents’ farmstead is only a stone’s throw away from Mäetaguse. He thus claims to feel the need to do something for his community. When he took office in 2015, his predecessors left him with a meticulously renovated manor complex that needed to be combined with a well-considered public space. When asked about their ability to value space, he says that he feels the inner need to make his environment more beautiful and thus set a goal for himself to bring about a positive change in the local living environment. He has been lucky to have worked with professional people and also his previous cooperation with architects in Toila and Jõhvi has taught him to look around with a keen eye and take notice of architecture and the urban space. However, he had an eye-opening eureka experience when meeting Tiit Kaljundi. It happened in the course of the spatial design project in Toila in 2003 when he as the head of the local municipality cooperated with architect Tiit Kaljundi, urban planner Andres Levald and geologist -cartographer Eduard Pukkonen. It was Kaljundi who guided the young local government leader to note and value space and also to see and analyse the big picture. He similarly made the recommendation to consider the location of new buildings highly carefully, first by densifying the central area and consciously keeping the population compact. His experience with large-scale public space projects stems from Jõhvi where in cooperation with Ra Luhse and Tanel Tuhal they designed a kindergarten and a promenade across the town connecting the park area with the town centre. The given success story also gave him the courage to undertake a major project – combining the heart of the manor estate into an integrated whole – in Mäetaguse.

The local environment specialist Martin Miller is the client representative doing most of the communication with landscape architects. He came to work at Alutaguse parish immediately after defending his Master’s degree in landscape architecture. The first important thing for the local municipality was to find a good partner whose vision would correspond to the municipality’s expectations, especially as the brief was very general and the project development required close cooperation. The brief for the park was put together by the local municipality and the school. The landscape architecture project was something between a cheap and value-based procurement: the price constituted 60% of the procurement while the idea and additional parts totalled 40%. The aim was to have a draft plan that could be both developed further and implemented gradually. As it was not so to speak a real competition, the compliance of the solutions with the initial plans and wishes was assessed by a committee including the local government people. As an architect, I am surprised that they did not involve experienced spatial design specialists, however, they were lucky to have also the accomplished landscape architecture office Tajuruum among the tenderers.

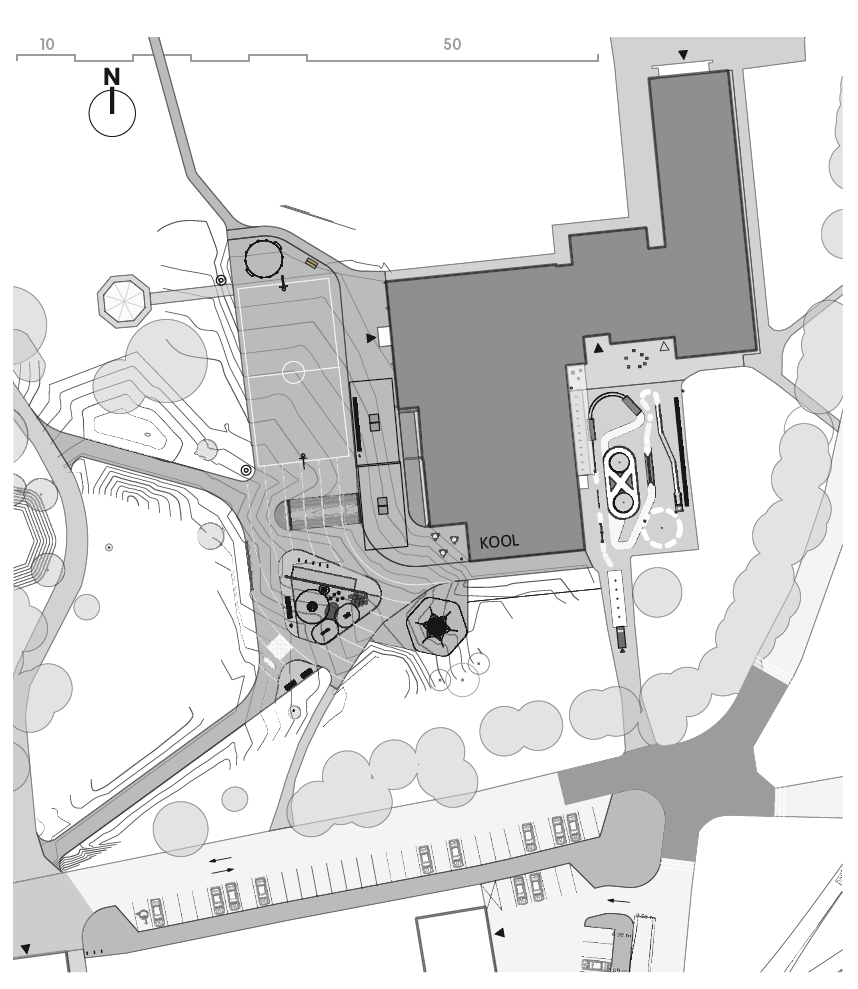

The initially very general brief evolved into a thorough and comprehensive landscape project considering also the future needs. One of the most interesting parts of the landscape project is the solution for the school outdoor area. The fashionable active playground is a good example of the symbiosis of a mandatory ball game area and a creative space for various activities. This part of the park clearly shows that when the users are today’s children with their skateboards and kick scooters, contemporary design can complement a historic park very well with no need to flirt with pseudo-classicist design tricks.

There are 136 students in Mäetaguse Basic School who live either in the borough or within a 15-kilometre radius. The kind and energetic headmistress of the school Veera Sibrik says that it is highly important to take care of each other and their school. The school motto is “Everybody feels good at school”. A learner-friendly school is reflected in an environment where regular children study together with children with special needs with their mother tongue both Estonian and Russian. Mäetaguse school is a good example of an environment integrating differences. The general atmosphere is warm and supportive. Although built according to the standard project of the 1980s, you can find small changes everywhere – there’s a rug in the middle of the elementary school classrooms, the desks are placed in a circle or in groups and the layout of the common areas encourages communication, resting as well as various activities. The interior design of the handicrafts building leaves many of the city schools in shade as the options for creative manual activities are truly impressive. The school has also joined the pilot project Schools on the Move and they are proud to show their large gym and weight room that are both in active use. However, the contemporary environment encouraging people to move is best reflected in the yard area described above, also in the gym campus integrated with the manor park and the track and field stadium. The modern sports facilities are well woven into the historic park environment. Then again, they can be easily accessed also by the spa guests. The route from the school to the stadium meanders along winding paths under the tall trees in the park that will certainly have a strong impact on the children as a powerful spatial experience.

In small places, an important role is played by the decision-makers. It is their energy, knowledge, experience and values that largely define the way other people in the community will come to perceive and value the neighbourhood. When comparing small towns and boroughs and setting them in a wider context, it must be admitted that small places are often considerably more open and flexible to changes. They tend to be more willing to go along with pilot projects and experiments, and thanks to their small size, the changes can be implemented faster. The same applies to Estonia in general when considering the European or global context. In large systems, exciting changes often occur in the periphery where there is no pressure from the centre and they can rely on their own unique qualities. The dialogue between the centre and the periphery is best observed in their mutual interaction – small places emulate the culture and technological achievements of larger places, while the latter tend to search for unique phenomena and ideas from the border areas.

Coming back to the people, the greatest challenge for the initiators in local governments is involving other people in their ideas. The locals often find it difficult to adapt to the changes as it requires an additional effort and it’s easier to carry on “as they always have”. The need for a change must be convincingly justified. According to the initiators of the Mäetaguse landscape project, their lesson was that people need to be involved at an earlier stage and allowed to make their suggestions. This has now been applied in Iisaku, Pagari and Tudulinna boroughs where people have positive expectations for the new projects. As there is never enough money, it was a conscious decision to make only long-term plans. So even if the realisation of the entire project may take ten years, they have an overview of the big picture with each stage adding another important piece.

Similarly, the work with the public space in Mäetaguse has not been completed. The contrast between the heart of the manor and the rest of the borough is striking. There are abandoned ruins of agricultural facilities and a barren wasteland right across the road. Next to the local shop you notice a white brick apartment building from the Soviet times with boarded up windows. The surroundings of the prefab buildings are neat and tidy but there are few signs of people using the common space around their houses or of any attempts to add value to it – at times there are no trees or bushes planted between the buildings, not to mention any benches or shelters to provide the means for activities and communication. The environment of prefab buildings is traditionally bleak and car-centric – the doorways are densely packed with cars. Fortunately, the tall trees dating back to the manor times extend also farther beyond the park and so the surroundings of the kindergarten and partly also the area bordering the apartment buildings are somewhat alleviated by the old trees. However, it is interesting to note that the beautiful heart of the manor has had practically no impact on the daily environment of its surroundings – the sense of beauty and caring hands perceived near the school and the manor park have not extended to the immediate surroundings of the people’s homes. I leave Mäetaguse wrapped in December darkness with mixed feelings hoping that in the years to come the local government’s initiatives dedicated to the evolution of the public space will also extend beyond the heart of the manor complex.

KATRIN KOOV is an architect and President of the Association of Estonian Architects. Working at the architecture office Kavakava, she was the co-author of several public spaces and buildings. She teaches at the Estonian Academy of Arts and School of Architecture, she has also curated and designed exhibitions as well as edited the architecture journal MAJA.

HEADER photo by Johan Huimerind

PUBLISHED: Maja 99 (winter 2020) with main topic Rural Insights