The architecture offices born at the time of economic downturn are inevitably much less inclined to undertake bold experiments than the ones whose beginnings are rooted in more auspicious times. Instead, what becomes crucial then is an ability to make the most out of the limited resources in a nuance-sensitive way. Thus, KUU architects are, in a sense, minimalists, yet they do not seek minimal form, but look for opportunities to efficiently utilise the existing contexts in order to create spaces that empower its users.

Interviewed by Eik Hermann

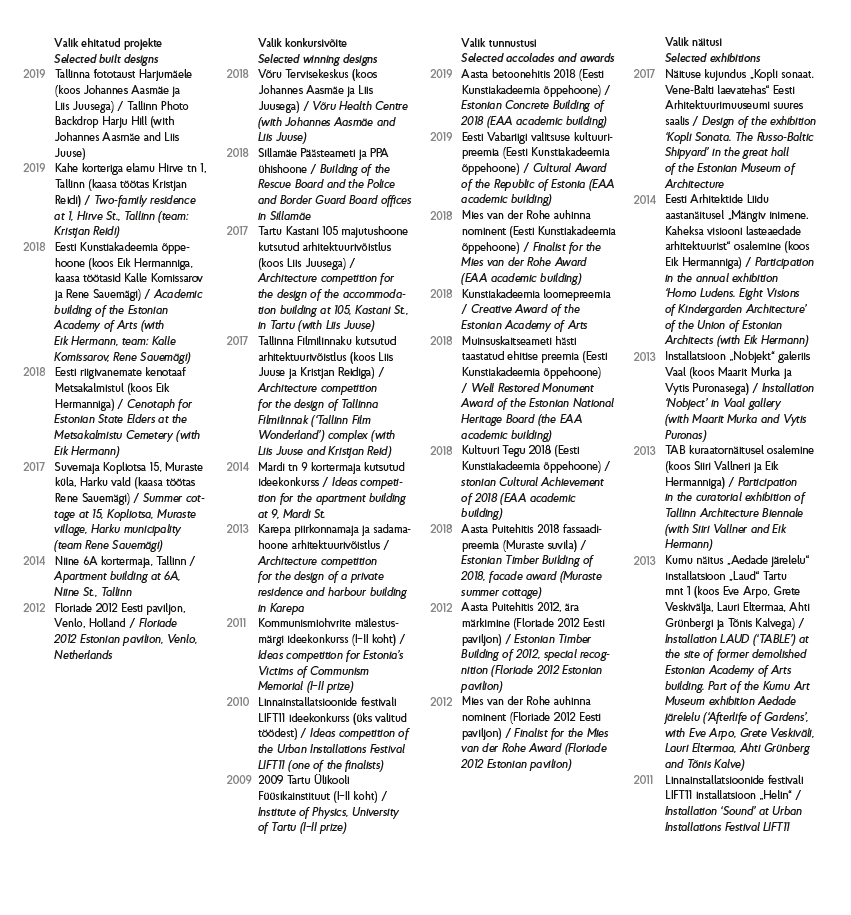

JOEL KOPLI (1983), KOIT OJALIIV (1980) and JUHAN ROHTLA (1982) have worked as practicing architects since their graduation from the Estonian Academy of Arts in 2008. As of 2011, they run their own architecture office KUU Architects, where they collaborate with Johannes Aasmäe, Eik Hermann, Liis Juuse, Kristo Põlluaas and Kristjan Reidi. In 2014, they also returned to their alma mater, assuming the duty of supervising the course projects of architecture and urban design students.

Eik Hermann: Let us start from the beginning: after graduation, you worked both a day job and a night gig. How did you manage it?

Juhan Rohtla: I think it is a relatively widespread norm, at least in Estonia, that you get your first education from school and then your second education from an established architecture office where you work after graduation, and only then you will be ready to start your own office. The offices where we worked—me in 3+1, Koit in QP and Joel in Pluss—provided us with the experience of a working office model and the assurance that, with the same model, we could also make it on our own, more or less. Already as students, our eyes were set on having an office of our own.

Koit Ojaliiv: Officially, we started our office only as late as 2011 when we won the Floriade pavilion competition.

Joel Kopli: Our first competition bids went out under the names of established offices, as we ourselves did not have the necessary qualification. And initially, yes, these were side gigs for us, secondary to our day jobs. When we did the Floriade pavilion design, we set up our working space in a conference room in Telliskivi Creative City, which we rented together with Linnalabor. They used the room in daytime hours, we took it over in the evening.

KO: Joel was the first to commit himself full-time to our own enterprise, Juhan was the second and I was the last one, joining my partners only in 2014.

EH: Did any of you also consider other possible options or was it already certain from the outset that these are the people with whom to start your own office?

KO: Juhan and I did our first competition designs together when we were still students. After graduation, our decision to try and involve Joel in our projects was just a lucky chance. So there was nothing planned or deliberate about it.

JK: We had a string of successful competitions at a very early moment. That experience certainly boosted our belief in our partnership’s potential.

JR: Ours would probably not have been the only possible combination, but I guess there is no reason to fix or change something that already works. And as a three-piece unit we can still join other teams for any particular project we like.

EH: Where do you position yourselves with regard to the older and younger generations?

JK: I suppose the financial crisis of 2008 marks a watershed of sorts for us. There is a distinctive difference in what went before and what came after. We graduated right at the moment of transition. Before, bolder and more daring designs were favoured—sometimes it even felt like the craziest, the better. Then, after the crisis, everyone was cooled down. Especially for the next four or five years, you had to be extra rational in explaining your design decisions.

KO: Today, the winning designs must stick to things which are known to be reliable and already proven to work. Maybe this is about to change.

JR: It is because we entered into existence exactly when the economy was at its lowest that we are set apart from the preceding generation of architecture offices. We lack their characteristic radicalism.

JK: Sure, but they have also changed their attitudes and adapted to the new reality by now.

JR: Yes, but we were forced to adapt immediately. They were still being carried along by their earlier momentum when we were just starting our engines.

KO: As to the later generations, I certainly feel a difference in the youth of today. When they come to school, they come with a focused purpose to study. It could be just my personal impression, but the Bohemian spirit and freedom to do stupid things was much more prominent in the earlier days. Your school years were not simply a rational investment in your future, but also the time to have wild parties, and to experiment and err.

JR: Our office has been fortunate to be among those who could still make a considerable number of real buildings. Many who arrived on the scene just a fraction later were forced to start inventing new niches for themselves in order to survive.

EH: In one of his interviews, Toomas Tammis explains the difference between the older and younger generations of architects as follows: while the older generation always had a distinct and recognisable personal style, the virtue which the newer offices prize above the rest is the architect’s ability to create designs in many different styles. What do you think, is it important at all to develop a personal style? Have you developed one?

JK: For that last question it is perhaps easier to get an answer from someone who has an outsider’s perspective. Personally, I do not think that our works exhibit any specific style or character. Of course, certain designs do have a similar character or function. We can recycle the ideas which we have already conceived before and learn to avoid our earlier mistakes. Regardless, each time we carefully disassemble the entire package and look, before putting it back together, if we can find either something that is still missing or something that is needed no longer.

JR: This is what we were taught to do at school where we were constantly asked why we do this or why we do that. We always had to keep reacting to questions and problems. That can also be called sensitivity to context, if you will, or attunement to one’s environment.

KO: If we say our projects are very different, we can ask whether their difference is in their form or in their content. To my mind, we always keep discussing certain central essential questions from one competition to another. What is the contribution that a certain building makes to its surrounding public space? Which elements from the surrounding environment do we want to see reflected and enforced in our designs?

EH: The desire to find the reason and justification for one’s activities could also be seen as an indication of a concept-based way of working: the goal is to uncover the idea of the room to be created. In your case, it can be said that your concept emerges from the context(s). Reliance on this lifeline between the context and the concept can create difficulties in situations where context offers only negligible input.

JR: Even an empty field has context. It may lack the specific spatial built-up context, but there is always something. There is also the metacontext, such as the client’s or the public’s expectations for the project, which may sometimes possess a much stronger contextual impact than the immediate physical context of the adjacent buildings or the general character of the urban locality. Contexts, limitations are what we strive on as architects. For each project, these are different, and the matter of imposing a personal style on the context becomes a non-issue. We do not always have to see them as obstacles, that is, something which we need to overcome, but as a riverbed into which we can fit ourselves to flow. And it is always possible for our reading of the context to be wrong, so to speak. If that style of ours is to be found anywhere, then it will be it in the way we read the context and what we do with it.

EH: It has always been my impression that, when doing projects together, it has been to our advantage when the playground has been relatively restricted.

JR: In hindsight, sometimes it feels as if we ourselves like to limit our options. Several design proposals for the EAA building which we competed with envisioned a far more extensive demolition and restructuring of the existing building.

JK: In our case, it also had to do with our client’s limited budget.

JR: Yet I do think that our personal preference minimal interference also comes into play. For example, in the case of the cenotaph of State Elders, we worked with what we already had—with the ground surface which we raised only the tiniest amount. Practically the entire bulk of the mass was already there, on the spot.

JK: It may also be related to the fact that when operating in a strictly defined context, consensus as to how to move forward with the project is easier to reach.

KO: We could say that the context can sometimes be dense and sometimes sparse.

EH: ‘Density’ and ‘sparsity’ is actually a very apt pair of words to describe the force lines emerging in the contexts surrounding the project and the extent to which these are clearly perceptible in a particular context (be that spatial, political, economical, psychological or something else), as well as the extent these exert a pressure on the project to move towards a particular solution. The pressure exerted by ‘dense’ contexts would be focused and strong, while the effect of ‘sparse’ contexts would be much more diffuse leaving the door open for a variety of equally viable solutions.

KO: Time has sometimes also been described as ‘sparse’ or ‘dense’. A sparse context may leave us too puzzled as to what, in fact, is the principal value to be found there which we should reinforce, whether it is the public space, nature or something else.

JK: Or instead, we could tone everything down even more in order to reinforce the existing sparsity.

KO: And sometimes, in our discussions, we never seem to find agreement.

EH: Let us try a different perspective. Certain architects seem to view a building essentially as a large sculpture: for them, the building’s external appearance and looks is what seems to matter the most. In that case, the assembly of the outer shell won’t cause much difficulties.

KO: For us, facade design is one of the most challenging tasks. The creation of the building’s internal space comes easier to us. In that department, our discussions also tend to be more fruitful and productive. But when we need to start thinking of how the building’s external shell might look like and the building’s concept fails to provide us with any clear indications regarding its package, we will be in trouble.

JK: External decoration of buildings, creation of just plainly beautiful facades, is certainly not our forte. Yet, to say that our facades have been bad…

KO: I am not saying that they are bad. What I am saying is that if the outer form of a building cannot be derived from its content, then we will be struggling to create a facade which would transcend the application of a handful of mannerist techniques.

EH: In contrast, a sculptor-type architect would likely handle this task with a relative ease and would not be vexed by any potential incongruity with the concept or the contexts. For a ‘sculptor’, the primary interest would rather lie in the creation of something avantgarde in the outer form of the emerging structure.

KO: Perhaps. Our preference has indeed been to create such facades which would not appear incongruous. For example, the facade of the Niine 6a building was created as an afterthought to the entire streetfront that was filled with triangular gables. That rhythm was also extended to our building. And since we wanted the volume of the building to remain readable, we needed ribbed cladding, any balconies or indentations of the facade would have made it more difficult.

JR: I would say that the form emerged there at the confluence of the building’s internal logic (logistics and use patterns of the apartments) and the considerations of the exterior you describe.

KO: True. And the amount of new facade we had to create for the Academy of Arts building remained relatively modest. On Kotzebue Street, the windows in the new section took their rhythm from the older parts. On the side facing Põhja Boulevard, the facade of the new section emerged from the considerations of the interior in relation to the spatial organisation of seminar rooms, as well as the idea that the new facade should be clearly articulated as a distinctly new structure with a bit more vanity to its appearance.

JK: And where we wanted to facilitate immediate communication between the lobby and the street space, or between the lobby and the inner yard, we used 100% glass facade.

KO: That is an example of a large building whose facades we did not have to invent from scratch, but which formed themselves, so to speak.

JR: While sculptors, to use the same metaphor again, mold their clay with the movements of their hands, in our case, the figurative hands which shape our design are the various contextual factors.

EH: Sometimes, however, the pressure exerted by the ‘hand’ of contexts remains rather weak. Or to be precise, the interactions between the contexts, the concept and the design are necessarily mediated by the architect’s imagination. Sometimes, the architect can simply fail to consider important contextual factors, as these are more hidden and cannot be fully appreciated without delving deep into the nuances and historical background. Here, however, architects can be helped by the organisers of architecture competitions who prepare the guidelines for the participants. For instance, in the case of the EAA, without Toomas Paaver’s excellent preparatory work with the competition brief, we would certainly have missed quite a few things. If no such work has been done, however, the contextual approach will require a thorough and time-consuming immersion from the architect for the vague force lines to become discernible and start to converge into a concept.

JK: Indeed, this way of working requires significant time and effort. We have also often discussed among ourselves that, considering our approach, we would have to significantly increase our preparation time for competition submissions.

EH: Several architecture offices have simplified their task by turning some of the many variables into constants. For example, regarding the choice of possible materials, some have limited it to local timber only. In fact, a similar tendency can also be seen in some of your works: namely, in the Floriade pavilion and its sequels. Yet in contrast, some of your designs make only a minimal use of wood. So it seems it is unfounded to say that you have a favourite material?

JK: In general, we prefer ‘honest’ materials, be these stone, wood or concrete.

JR: But to name just a single favourite among them is indeed impossible.

EH: In the Academy of Arts building, would it have been conceivable to use gluelam instead of concrete?

KO: I would say that our choice of concrete was, in this case, also contextual. The oldest part of the building complex, designed by Eugen Habermann, is among the most remarkable historical concrete structure factory buildings in Estonia. Bevelled beams, extremely thin concrete slabs. Secondly, the same complex also included various parts that had been built in Soviet times, at places carelessly and at places properly. On the plus side, the encased concrete there is excellent.

JK: So, the complex can be seen to encapsulate the whole story of the Estonian concrete construction.

KO: In that regard, the addition of the brand new modern high-quality concrete extension in the complex certainly has its point.

JR: Perhaps the answer to your question is that our choice of material is context-based. The number of different materials we have worked with is not large, but the experience we have gained with working with each of them is relatively extensive.

EH: Could you think of any principles that always remain important for you?

KO: We could come up with a few slogans, yet every project still remains different. Our ideal project would be such where neither we nor the client knows at the outset how the end result might turn out. Even if the client claims to know this when arriving at our office, our analysis will lead to something else, which the client will be far happier with instead. Our satisfaction would also be complete by having managed to introduce an additional quality into the surroundings of that building or by having reinforced some of the existing qualities. What we accomplish is not the creation of a separate new object, but the accentuation or highlighting of the already existing qualities in the building’s environment.

EH: Indeed, instead of principles, having a specific attitude or taste regarding their activities may be far more important for an architect. For instance, Tuomas Toivonen, when doing critiques at school, is fond of asking, ‘Why so much intervention?’ Equally, in the same situation, someone else could ask just as well, ‘Couldn’t you have done more?’ For example, in their presentations and talks, Lacaton & Vassal stress that their goal is to give as much as possible to the users, to make their spaces luxurious.

JR: Lacaton & Vassal have a charming concept of luxury, in the sense that it does not mean the use of fancy materials or such luxury which the developers would often have in mind, but rather implies a generosity of space and light.

KO: At the same time, by following the logic of Lacaton & Vassal, we could have packed tight the entire EEA plot, building it up cheaply, yet cleverly. In a way, having very limited space and making the most out of it by clever/smart solutions has a special appeal of its own. It’s a bit like in Japan where cramped space necessarily forces an overlapping of functions. It gives rise to dense space, dense time, dense context and so on.

EH: Those two examples which I mentioned are actually not quite the opposites they seem. Lacaton & Vassal strive for luxury, but their goal is to attain it with strictly limited resources. On the other extreme, instead, we would find someone whose luxury means expensive things and indulges in extravagance, excess and self-importance.

KO: I don’t think anybody makes such architecture in Estonia.

EH: I think that some architects certainly would not rule this out, but the limited resources do not permit this.

KO: We would also not rule out such a possibility, but we simply do not feel that excited about it. What is far more interesting, for example, is the assignment we are currently trying to solve with sophomore EAA students, which is the nursing home of Koeru. Its clients represent an extremely marginalised section of the Estonian society. The limited budget here also keeps us focused on the very same question: how to accomplish the most with doing the least.

JR: In my mind, it can be likened to an empathy studio. Since the problem is extremely acute, set in a strong and powerful context (an already existing building shell; the needs of the elderly, including those of dementia patients; an aging society that nevertheless continues to marginalise the aged, etc.), then it requires the students to adopt an approach which they will hopefully find useful in their future projects as well. Here, we can keenly feel the relevance of the principle that an architect should contribute more than necessarily required. Norms, more often than not, only set the bare minimum which is not sufficient to ‘empower’ the disadvantaged or unprivileged users of the building or public space.

EH: The word ‘empowerment’ is also close to my heart. It also connects with the principle of minimal intervention: if you help someone too much, they may become too reliant and helpless. In the context of spatial design, that would mean the creation of excessive comforts or, more generally, relieving the users entirely from the responsibility of making any spatial decisions, stunting their imagination and capacity to actively involve themselves with the design of their space.

JR: Regarding comfort, the level of effort required from the room users simply should not be that extreme as to cause them to be drenched in sweat after climbing to the top of the stairs. Rather, it should be modest. On the other hand, making someone’s life too easy and comfortable gives rise to a different kind of marginalisation: it enables people to get stuck in their comfort zone and cuts them off from the changing actuality.

KO: Keeping in mind the principle of minimal intervention, it is entirely rational to leave the design short of completion, especially in the case of public buildings and rooms, and say that from this point on you should be able to carry on yourselves. In the EAA building, we left a number of rooms in such an incomplete state, so that their users could eventually have a final say in their design.

EH: The question becomes: should the EAA building be regarded as an exception, since its users can be expected to be extraordinarily active and involved, or can we apply the same principle successfully to other typologies as well?

KO: Leaving the interior finishing incomplete is certainly not a universally applicable concept. However, flexible spatial layouts, allowing for adjustment to the needs of different users, is very much something that can be used in a wide variety of places, from kindergartens to law offices.

JK: And the diversification of social/public, semi-private and private space is also a principle that can be successfully applied in many different contexts.

JR: In the case of the EAA, the starting point for our work was the outer shell of the building which, as to be expected from a factory, had already originally been designed to be easily adaptable. We simply tried to avoid reducing this flexibility unnecessarily.

KO: We also created rooms without any clearly defined purpose of use. Even a corridor was never just a corridor, but a place where to hold examinations, prepare food, retreat into a nest, etc.

JK: At the same time, of course, some people always want their space complete, neatly structured, with no loose ends sticking out anywhere. Not that they necessarily lack the ability to personalise space, but they simply prefer not to waste their time on it.

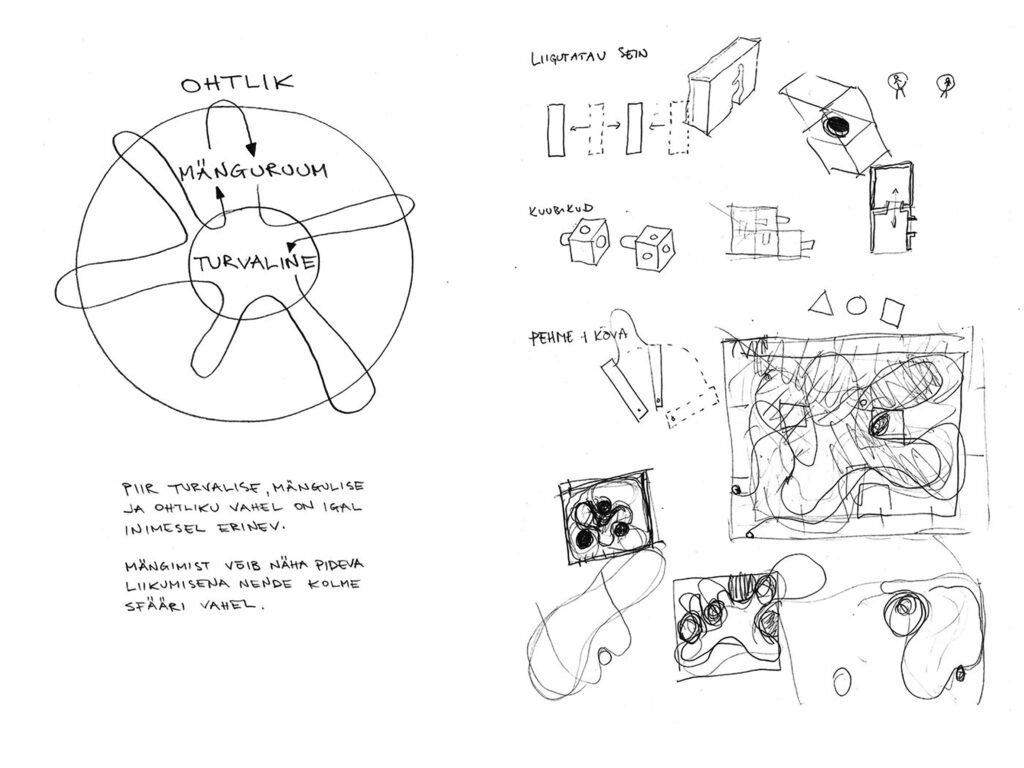

EH: I have tried to argue that having an incomplete room is empowering to its users. However, which kind of incompletion is most empowering? Can we say that an empty room is its extreme embodiment or should we say that actually there are far better examples of it? We just spoke about sparse context. Can the same also be applied to the relationship between the room and its user, saying that a room that is too sparse offers less freedom to its user than a room that already contains all sorts of spatial elements as pointers that nudge the user towards a variety of possible actions?

JR: While we talk about empowerment, the comparison with a monkey cage in a zoo may perhaps seem a bit far-fetched, yet, if we think about it, the monkey cage also comes equipped with an array of fixtures and fittings (ropes, hoops, high platforms) which the monkeys can claim for themselves. In order to use a room, one must have a personal relationship with it, and there are elements which make its establishment easier. In some cases, these can be architecturally incorporated in the room (such as the so-called inhabitable wall in the EAA, different surfaces, or even just a small empty space somewhere), but in other cases, the users can also introduce new elements themselves (e.g., the black box or white cube typologies).

JK: Perhaps the key lies in offering a multitude of rooms with different character in the same building, so a diversity arises, which makes it possible to choose between them and find the one that matches best the specific nature of the particular activity. In a super-flexible room, however, no-one will be really comfortable.

But it is also possible to avoid making any moves that unnecessarily limit the user’s existing options.

EH: Here we could also touch upon the relationship between standardisation and empowerment. Henry Plummer has written that perfectly comfortable stairs reduce the bodily experience of using them to nothing and dull one’s senses, while certain stone stairs, built by hand, with every step slightly different in height, force you to notice your body and the environment you inhabit at the moment. That is also empowerment.

JK: That is true. For example, if a football stadium is frozen over, in addition to your normal bodily movements which you are accustomed to, you also have to make such movements which help you to preserve your balance on the ice. In that case, doing physical exercises offers greater diversity than usual, since it involves such muscles which you normally do not use.

KO: I would also like to use the same analogy in the context of our profession. The entire construction sector is thoroughly standardised. Staying in that environment for longer periods of time reproduces the same standardised order within yourself. If for 15 years all that you do is design, naturally you will be desensitised.

JK: And desensitisation is the cause of all those run-of-the-mill design proposals.

KO: To snap out of it, you need something that breaks your daily rhythm, or a change of environment. I have personally considered to take up painting, for instance.

JR: For us, exhibit design, offering a chance to do quick exercises in spatial design under far less restrictive conditions, also serves the same purpose. Sometimes, interviews have also had a similar effect, when you need to articulate things which you normally would not have to.

KO: Yes, longer breaks in the exchange of ideas and thoughts regarding important matters between ourselves may increase the chance of unexpected clashes during competition preparations. It may turn out that the person with whom you have worked side by side for such a long time may hold radically different views in a certain very important question.

JK: We still agree on the things which matter the most. We can and do have our differences of opinion and this tension is what makes it all interesting and worthwhile. Without the intrigue, I would call it a day and pack my bags right now.

EIK HERMANN lectures in philosophy and practice-based theory at the Estonian Academy of Arts and also serves as the Co-Editor-in-Chief of the Ehituskunst magazine.

HEADER photo: (on the left) Juhan Rohtla, Koit Ojaliiv, Joel Kopli. Photo by Renee Altrov

PUBLISHED: Maja 96 (spring 2019), with main topic Spatial Diversity