To Be at Home Everywhere 〉 Joonas Hellerma

River Town Tartu. Four Competitions for the Banks of River Emajõgi 〉 Andres Sevtsuk

New Ways of Living 〉 Pille Epner

PERSONAS

KUU architects: Between Concept and Context 〉 Interviewed by Eik Hermann

SPATIAL DIVERSITY AND RELATIONS

A Phoenix Risen from the Ashes 〉 Carl-Dag Lige

Valuable Individual Objects — What and Why 〉 Triin Talk

Do Not Lead Me Anywhere, Let Me Be Lost 〉 Andres Kurg

Guiding in Architecture 〉 Gregor Taul

SPATIAL DIVERSITY

We are accustomed to talking about the importance of biodiversity as it is the foundation for our survival. Yet what about the diversity of our built environment? The process of globalisation responsible for mediating our culture, knowledge and skills is inevitably accompanied by a contradiction that often occurs when information is exchanged – a non-discerning insight. Are the faces of (down)towns receiving refreshment procedures identical only at first glance, or are we witnesses to a loss of spatial variety much like nature is seeing the extinction of species? Now, with Estonia more prosperous than ever before, we can feel the urge to “finally fix the built environment, make it new like it is elsewhere”. This often merely preludes trendy decorations that are unaware of our natural spatial abundance – spatial configurations originating from various periods and practices that have survived largely due to our lack of affluence.

Space withdraws and storages wisdom and experience from accommodating our lives. Various strata of our culture, tiny bits and associations are all wrapped into our spatial heritage, making it a unique combination. Becoming involved with space leaves behind traces and sediments of practices that offer a firm stepping stone for future users. It is like our spatial DNA that lives on even after we are gone. How can we approach this heritage in a way that enables it to function in the present day – diverting it from becoming historical ballast and encouraging it to participate in life, revitalised? What can we do to support the gene expression of our spatial DNA so that this precious heritage could change, adjust, evolve with us?

Change is a natural part of the world. For old buildings to function we must renew them when necessary. Producing associations between old spaces and modern conditions requires exquisite contextual sensitivity, a specific type of alertness. Eduardo Souto de Moura, the Portuguese architect who won the Golden Lion at the last Venice Architecture Biennale, has said: “If we go too far we will spoil it, if we don’t do enough it won’t work /…/ The only way to preserve heritage is to live with it and use it – only everyday living transforms it into something and gives it heritage status.” Nothing short of life is at stake, the question of who we are and what we need in the here and now. How many changes are necessary, how many old connections and reference points need to survive? Deciding on these topics requires openness and freedom of thought.

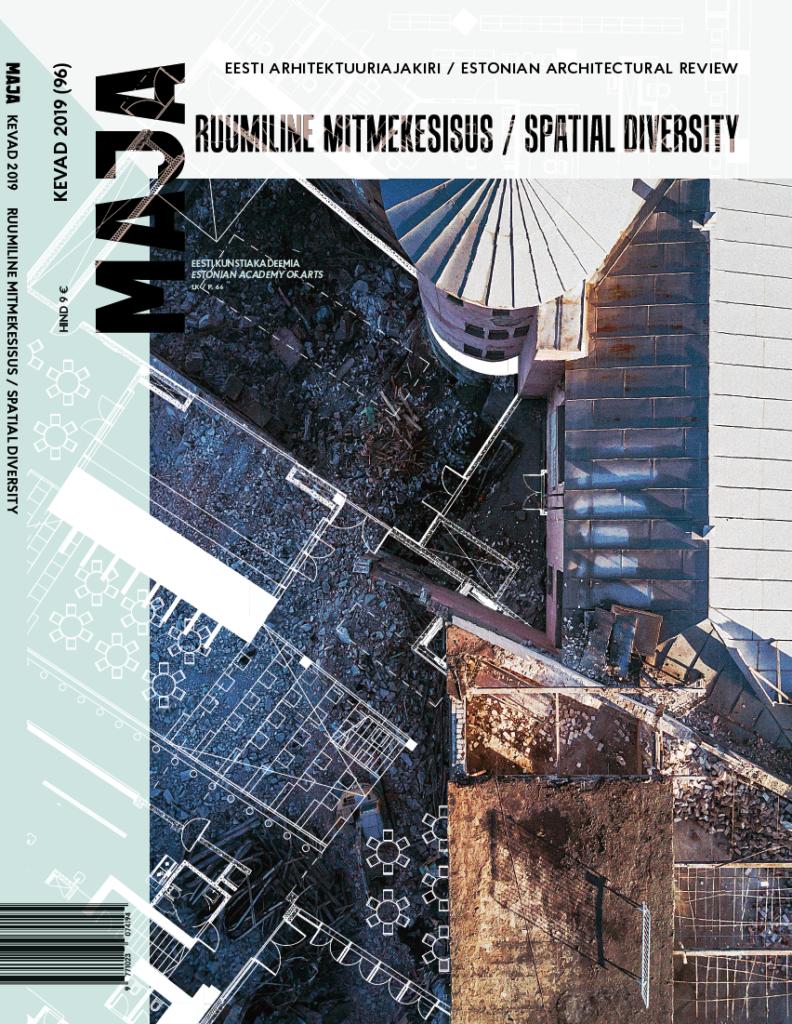

The new home of the Estonian Academy of Arts was recently completed. It is built on the site of the former Suva hosiery factory, a complex consisting of at least ten different historical completion phases. The new building sets itself in a deep-laid relationship with both the old factory complex, as well as the surroundings, by tying the loose ends of the existing context, and offering a new quality of spatial experience – one that is in-time, happening in the now, looking toward the future. It is both familiar and comprehensible – homelike in the best, most humanistic sense of the word, while also novel and surprising.

The new issue of MAJA is an investigation into how we can relate to spatial context, notice spatial heritage and translate it to the present day. Perhaps this is how the feeling of being home gets created, secure enough to open us up to new connections, and change.

Kaja Pae

April, 2019