RAPLA CENTRAL SQUARE

Architecture competition announced: 21.01.2015

Results published: 30.04.2015

Winning entry: „Holly“

Authors: Siiri Vallner, Indrek Peil, Kristel Niisuke (Kavakava Architects)

Landscape architecture: Kerttu Kõll (Sfäär OÜ)

Engineering: T-Model

Constructors: AS Infragate ja RTS Infraehitus OÜ

The square was opened in November 2018

Is EV100 Great Public Space programme revealing or creating the uniqueness of small towns?

What makes a public space great? Images of squares and boulevards with symbolic and ceremonial significance appear to belong to an era of the past, seemingly at odds with the diversity and spontaneity we expect from urban life today. If we speak of public space today, it would appear as something like a backdrop to the unfolding of informally defined activities, at once designed, yet ambiguously empty. The informality and ambiguity beg the question, what do we expect from the design of public space? And how might we begin to consider its successes or failures?

The recently completed square in Rapla by Kavakava architects is the latest project to be realized as part of the EV100 Great Public Space programme. Established as part of the centenary celebrations of the Estonian republic, the programme in cooperation with the Association of Estonian Architects organized a series of public space competitions in small towns throughout Estonia. The premise of the program is admirably forward-thinking, utilizing European Regional Development Funds to bring big city design skills to rural areas, while sparking discussions on the future of small towns facing increasingly uncertain economic futures.

Public space today appears ‘public’ in contrast to the increasing privatization of space and the perceived capitulation to the demands of the market. Ostensibly for everyone due to its accessibility, there is a distinct undertone of political idealism embedded in contemporary notions of public space. Inspired by a legacy that ranges from the agora of ancient Greece to the Baltic Way, to Occupy Wall Street; public space is seen as vital to the functioning of a democratic and free society, its openness allowing the possibility of assembly. In an era where architects are wary of being out of touch as the domineering master, public space has seen a marked emergence as the de facto site of their good intentions. Designs for public space inevitably lay claim to some form of indeterminacy for the will of the people to be exercised, allowing overt gestures of form-making to be reconciled as moments of urban delight in the service of the public good, not merely the whimsy of the designer. Public space is at once everything and nothing. Its emptiness makes other things possible: a place for a family to relax and have ice cream, the site for the latest pop-up market, a venue for community discussion and gathering. As Rem Koolhaas remarks, “Where there’s nothing everything is possible. Where there is architecture nothing (else) is possible.”

Urban ambitions

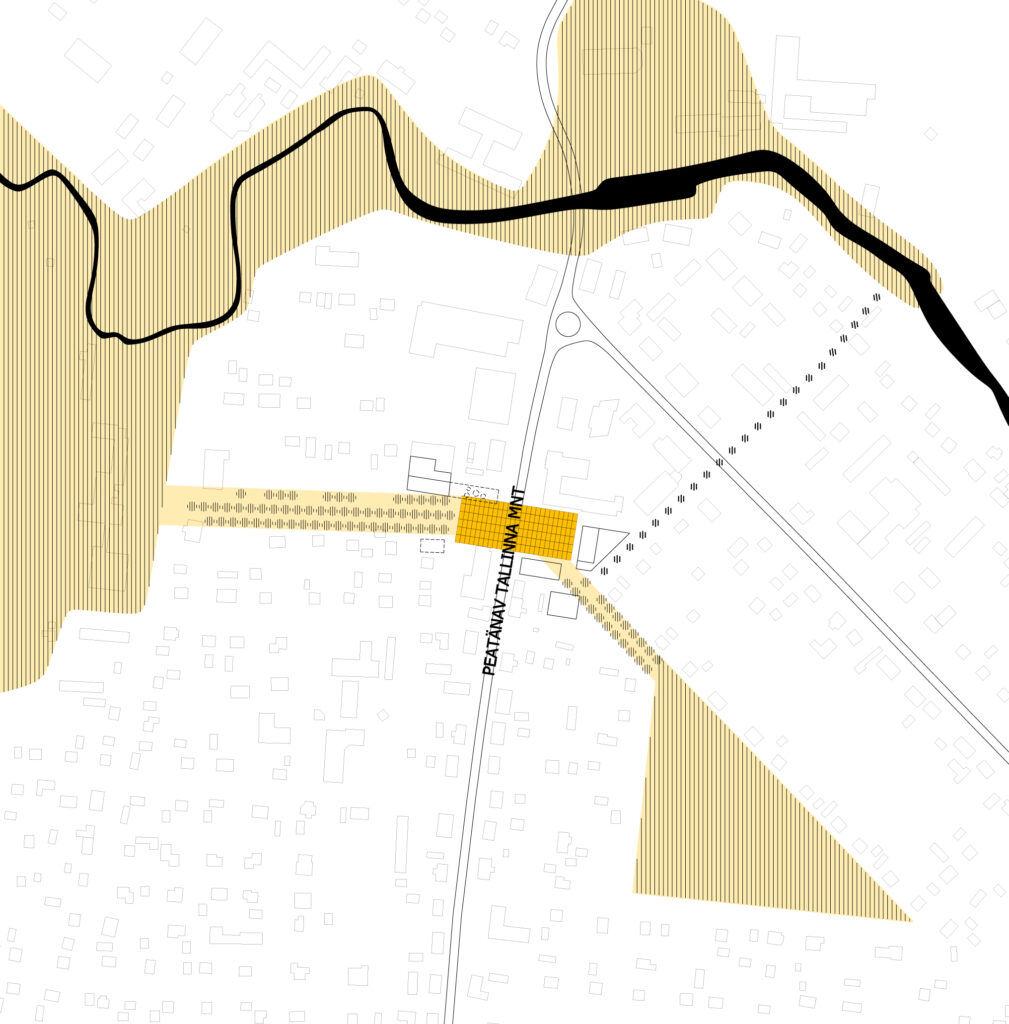

This ambiguous character is well embodied in the square in Rapla, won through public competition in 2015. The design by Kavakava, led by Siiri Vallner and Indrek Peil consists of a 40x100m public square cutting through the main thoroughfare of Rapla. The architects’ ambition runs high, seeking not only to create a new type of outdoor space for the community but also to create urban connections between the municipal centre, future children’s park and the Vigala river. The project faces one of this paradoxical predicaments of design that one sees so often, aiming to bridge two sides of a town that has been divided by a street that connects it.

The proposed solution is remarkably simple, a grid of concrete pavers that runs east to west, the deliberate nature of the gesture revealed through an inlay of dark granite that establishes grid lines corresponding to different widths — a larger grid composed of a smaller 5×5 grid of pavers. The grid is an effective choice, as even though the square is cut through by a street, standing at any point gives a unified field of lines revealing the logic of the grid and uniting the two squares into one. The real success of the project lies in how it has been able to produce such an explicitly absolute gesture (one that is so easily seen as unfashionable) by mediating the explicit geometry of the grid with playful deformations that gently slope to form smaller spaces with landscaping, benches and water features. Perhaps more than any of the other completed EV100 projects, it succeeds in operating as a form with urban ambitions, creating a strict geometry that operates as an ordering form in anticipation of future development. Indeed, this is the goal mentioned in the project description by the architects, with the rigidity and clarity of the square’s edges acting as a substitute for buildings yet to come.

Can pedestrianization save a small town?

Given the explicit aim to address small towns and to speculate on their economic futures, one can be forgiven if the ‘Great’ of the Great Public Space programme reads more like the great of Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again” than to the greatness symbolic of ceremonial public spaces of the past. As the programme website reads: “By making the hearts of the cities a more philanthropic and pleasing living environment, it will be possible to enhance entrepreneurship and avoid dilution of cities.” The public space investments are seen as a deliberate attempt to make small towns more attractive, producing the kind of lively streetscape that is so amenable to future development. This is the kind of ‘win-win’ scenario that is so frequently espoused by architects and policy makers when dealing with urban design. The intangible qualities of public space perform as both a social balm and as a stimulant for potential future development that can remain purely abstract. One can imagine the ideal outcome of such an endeavour, a renewed and lively pedestrian streetscape for cafes and nice restaurants, attracting the urban commuter or tourist traffic that would secure the town’s economic future.

This distinctly urban approach to public space has always seemed to clash with the reality of small towns. The urban reality for a city of 100,000 is very different to that of a town of 5,100, with only one bus that runs every 25 minutes. That is not to say the proposed economic benefits are impossible but probably unlikely to appear in this form. It is a tall order to claim that through the improved design and pedestrianization of public squares and streets, small towns will be saved from their uncertain futures. The challenge when architects get involved so explicitly with economic expectations is that they risk being held to their promises. As the young move to urban centres in pursuit of jobs and opportunities, their migratory decisions are unlikely to rest in some masterpiece of public space design. With declining tax revenues and reduced municipal budgets, the scale of the challenge facing the rural/urban divide requires an altogether different level of intervention.

A simple gesture

One can already see some of the pitfalls at the square in Rapla given the changes to the design from the competition phase to the completed project. The ambition of the design has been scaled back, the gentle curves now localized primarily on the east side of square where the grid descends into a water feature flanked by a series of steps that also double as benches. The overall effect is very different from that of the competition images, which had appeared as a sweeping topography that had been run through the subdivision command on the computer. At once abstract, yet delicious, it remains as designs often do, better on the computer screen and on paper than as executed in reality. The level changes of the terrain, previously shifting as much as two metres, have now been dialled back, most likely due to a combination of budget constraints and accessibility requirements. Formerly dramatic in relation to the scale of the human body, the effect now appears more as a series of accidental bumps on an unlevelled site. The subdivisions of the grid, now at odds with the requirements of the concrete paver size, operate at a different scale, the smooth lines of the flowing grid now instead draw attention to the slightest mistake in misalignment.

Given the simplicity of the gesture, one would have wanted perfection. The gentle curves calculated in unison with the dimensions of the concrete and granite, an Eladio Dieste masonry realized in landscape—understandably impossible without serious changes to the budget. The design may have been more effective if the architects had scaled back their ambitions early on in the design development phase: focus on creating the abstractness of the grid, a perfectly flat surface that reads so well in contrast to the loose and unplanned nature of the surroundings. The west side of the square, therefore, appears more successful despite lacking the flourishes of water features or steps. The relatively flat surface of the concrete paver grid punctuated around trees and plots of landscaping, a clarity of conceptual intention executed with simple techniques and materials to produce a spatial character that stands in contrast to the surrounding areas of the parish. In this manner, the design succeeds where the EV100 program has succeeded, it has created a distinct spatial intervention of a not insignificant scale, realized within a limited budget.

Public space as a modern coat of arms in a small town?

Rather than considered in terms of potential future economic benefits, we should consider the EV100 Great Public Space programme in terms of what it has delivered, a series of modest infrastructural upgrades to small towns, realized with some finesse by skilled designers. Its potential may rather lie in the open competition format which has succeeded in producing public spaces unique to each small town without needing overt symbolism or reference. Perhaps we should consider the EV100 Great Public Space programme as a contemporary version of a tradition that lies close to home, the municipal coat of arms. The one in Rapla used to depict a bridge set against a background of blue, a reference to Rapla’s historic limestone bridge, the only one of its kind in Estonia. Due to its historical significance and singular character, the bridge has become a matter of national concern, receiving regular repair and maintenance to its structure. It is also the backdrop to the festivities on Rapla day, where everyone gathers along the river.

This may be the kind of politics that begins to rally around the public spaces in these small towns, nothing as noble as the democratic decision-making of the agora nor as violent as the clashes of Euromaidan or Occupy Wall Street. But in a political climate of austerity and rhetoric around economic competitiveness, the EV100 Great Public Space programme serves as a modest reminder that these small towns have not been forgotten. The crest for Rapla was changed in 2017 after administrative reform added three parishes to the Rapla parish. As populations continue to concentrate in major urban areas, this move reflects an increasing tendency to group small settlements into ever larger administrative regions. We should remember that the rural/urban divide is not just a question of economic concerns, but as we have seen globally with the elections around Brexit and Trump — a political one as well. There may well be a need to ward off the political despondency that comes with the shrinking of small towns and cities, and as political representation becomes increasingly dispersed for small towns, the diverse spatial identities being produced through the EV100 programme in Estonia may be a place where politics can begin.

When I last visited the square in Rapla, it was one of those beautifully crisp winter days where the landscape is almost impossibly bright when the sun reflects off the snow. It was a Saturday, and there were a number of people out on the street bustling from the supermarket to their parked cars. The square was nowhere to be seen, the only indicators it was ever there were the linear rhythm of the steps leading to the flagpoles and tables on which someone had gathered the snow together into an impressively phallic mound. The roads were cleared of snow, easing the slow traffic of the bus and the occasional car. Maybe next year the square will be cleared of snow as well.

LEONARD MA is a Canadian architect based in Helsinki, he is a member of New Academy and teaches at the Estonian Academy of Arts.

HEADER photo by Siim Solman

PUBLISHED: Maja 97 (summer 2019), with main topic Architecture is an Art of Space