First, we must look at what qualifies as wasteland. It is fact that wasteland is a part of urban nature where the influence of human activity is clearly distinguishable. We might even go so far as to say that wasteland is manmade. It may include ruins, degraded and broken infrastructure, construction waste among other things. To phrase a definition, we might say of wasteland it is part of land that has been formerly used by humans, stood unused for years on end, and been overtaken by nature as a result. It is quite difficult to draw an exact line between what is wasteland and what is not.

At Tallinn University, we have investigated further into the wastelands of Lasnamäe and the following generalisations have been drawn based on those studies.

The attitude towards wasteland is currently user-based. There are many who do not see or notice wasteland at all and simply drive by it—mostly by car. Wastelands are as if non-existent areas on the map of human psychogeography, they are meaningless and invisible places. Another extremity values wasteland as a refuge for doing things that are normally deemed suspicious in standardised urban parks, such as making a bonfire. Such areas in Tallinn can be found in the Liikuri district and at Paevälja at Lasnamäe. Kurepõllu wasteland was the object of inquiry for Karina Vabson in her Master’s thesis. She has contoured wasteland as feminist space: it features a dovecote, women with strollers, the space itself is more child-friendly and has an open disposition.

Wastelands can thus have different characters: some may seem more dangerous or hostile, others friendly. It is not possible to introduce illumination everywhere, therefore, the presence of humans in a spatial context is one way to create a sense of security.

Wasteland is the destination for people who want to sunbathe, make bonfires, take their kids out for walks in strollers – people go there looking for quiet and a different kind of spatial experience.

Many use wastelands as a park or green area, something they feel is missing from their place of residence. These are people who engage in outdoor sports, walking their dogs, and enjoy sunbathing. Wasteland offers a myriad of alternatives for use. At Lasnamäe, the ratio of park area per resident is low as it is, wasteland is the main park area there.

Despite wasteland remaining rather unregulated and scruffy, the treading paths there filled with holes or missing entirely, people nonetheless prefer to spend their time there instead of strolling on official light traffic routes. Wasteland is the destination for people who want to sunbathe, make bonfires, take their kids out for walks in strollers—people go there looking for quiet and a different kind of spatial experience.

The pandemic of the past year has no doubt increased spatial inequality and showed the necessity and importance of wasteland for humans in particular. We have had to stay indoors for over a year, prohibited from engaging with normal daily activities. Those who have not had the option of fleeing to the countryside or summerhouse have had a rougher time. It was at Lasnamäe that this became especially apparent. Wasteland may well have been the only place where people could go to refresh during the day and get a chance to withdraw from daily routine.

It is quite a common misconception that wasteland is a place for drunkards. It is a belief that people who have missed the boat in life, lying there on their side, drinking beer, are the ones littering, not able to keep the place clean. This is not at all the case. Our students have performed observations at Lasnamäe and it turns out that the people who throw packages on the ground are pupils playing truant from school. Citizens sipping in the shades of the bushes have gone there simply seeking a chance to get away.

The term green gentrification is used in specialty literature. Gentrification aka middle-classification stands for a process where a region formerly occupied by the working class becomes the dwelling and activity site for a wealthier group, mainly middle class citizens. The constant rush to organise, upgrade and middle-classify everything that comes with green gentrification endangers wastelands in particular because of the tremendous pressure it places on building through and civilising everything.

New apartment buildings are being built in the immediate vicinity of wastelands and the concurrent attitude is that while we are at it, let’s tidy up this ‘desolate land’, mow it and make it into a proper park. Often people fail to realise that this already existing green area is more valuable in every sense than golf course lawn and trimmed trees, planted along straight lines.

We should not ignore the freedom that a wasteland provides its visitors: the lack of control, no predetermined guidelines on how the space should be used. Everyone is free to take their own risks.

The wastelands of Lasnamäe are also biologically versatile: they are among the most biodiverse areas in Tallinn. It is the case now as it was before they were built full of houses. Much of this biodiversity is probably gone, for example, at Paevälja.

There have been quite a few investigations into the biota of the wastelands of Lasnamäe that have come back with results indicating considerable versatility of insects, birds, and vascular plants in the area. Why not consider wastelands as the oases of urban nature? Why not direct their evolution toward ever wilder biomes, restoring the alvar grasslands and going from there? Wastelands provide us with an opportunity to detach from everything, to step out of the urban noise that surrounds us everywhere. When you stand in the middle of Lasnamäe wasteland, you do not even realise you are at Lasnamäe.

On the one hand, the building of dwellings endangers wastelands, on the other, large-scale road construction is a major risk. The wasteland near the Liikuri district in Tallinn can be drawn out as an example. It is a significant part of the green corridor, yet according to planning material it will be accommodating a bicycle road, connecting different urban districts. Smaller parts of wasteland that remain are thus highly valuable steppingstones toward the green corridor, connecting the different parts. Part of wasteland conservation is about shaping people’s attitudes. The concept of ‘controlled chaos’ might become useful here. People have fears that need to be resolved. Those who are afraid of snakes and ticks must have places in the wasteland that are accessible with a so-called clean foot, carefree, without the burden of fear. Next to these people there are plenty of others who are in love with this wilderness and chaos, who go out just to seek that and that alone.

In 2017–2018 we carried out a study at Paevälja wasteland in Tallinn where we inquired into the restorative capacity of wasteland for the youth and how they relate to it. Young people took half an hour to walk around there, explore the area and subsequently filled out a questionnaire. One of the questions that prompted an answer was, ‘Do I feel rested?’, and ‘Do I feel like I belong here?’.

We got some interesting results. For example, many of the respondents felt that a slightly dreary and wild environment suits their character. Syringes and pieces of glass were found annoying, but the unpredictable nature of wasteland was assessed as a positive attribute. One of the youths found the surrounding natural messiness and wilderness to be soothing and pleasant. The older the respondents were, the more suspicious they were of the wasteland—younger people seem to have more of an adventurous and open disposition.

We also need to discuss what type of wasteland is the most valuable. Ecologically speaking, the highest value wasteland is the younger kind, less than twenty years old. Versatility, not just in the sense of biodiversity but also in terms of reliefs and landscape form, is also important as it increases the variability of the biota on a broader scale.

I have spent a considerable amount of time discussing the wastelands of Lasnamäe but Tallinn has other large wilderness areas, for example, part of the Paljassaare urban nature reserve has many wasteland identifiers. Many wastelands have the potential to be taken under conservation. Another valuable wasteland in Tallinn is situated at Astangu, Haabersti.

PIRET VAHT s an ecologist, lecturer of Environmental Management at Tallinn University, and member of the Environmental Behaviour research group at Tallinn University.

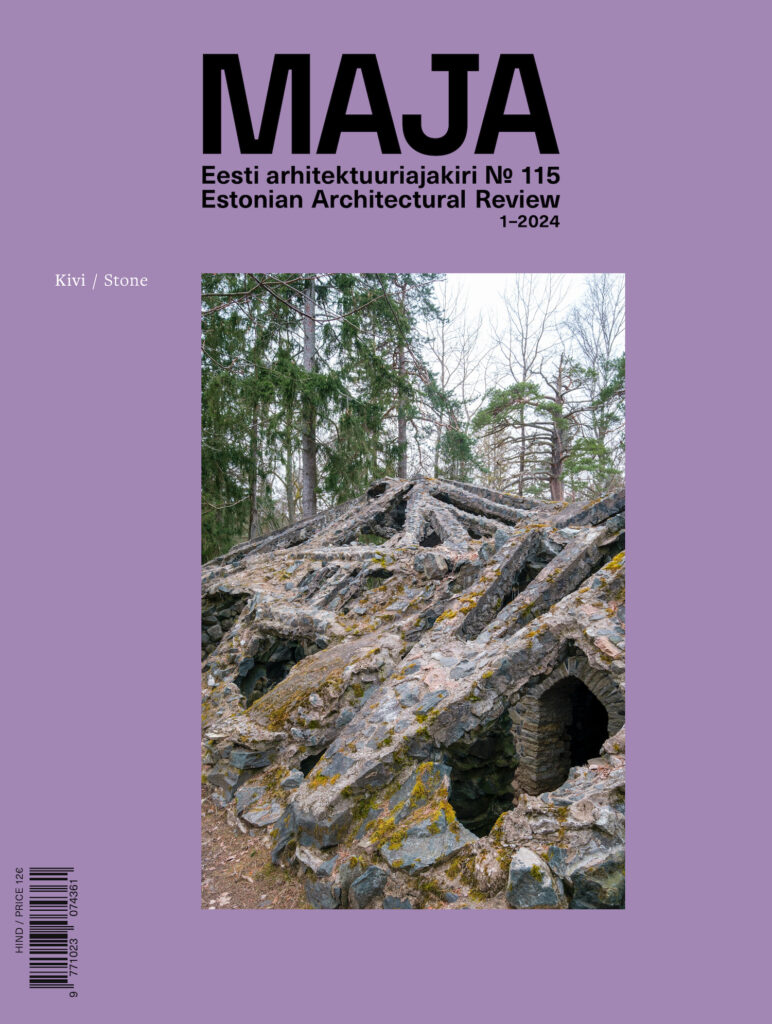

PHOTOS by Paco Ulman ‘Wasteland’

PUBLISHED: Maja 105 (summer 2021) with main topic Landscape Architecture!