Architect Johan Tali, landscape architect Merle Karro-Kalberg, architect Siiri Vallner, project manager Priit Õunpuu and interior architect Hanna Karits discuss their experiences of using limestone in recent projects.

KURESSAARE DAYCARE CENTRE ANNEXE

Architecture: molumba

Engineering: Klamber OÜ

Area: 300 m2

Function: event space

Competition: 2020

Built in: 2021

Location: Kuressaare, Eesti

Cost: ca € 500 000

Client: Saaremaa Municipality

Photos: Tõnu Tunnel

The extension of Kuressaare Daycare Centre has a limestone wall on one end, which feels crucial in determining the form of the entire project.

The exterior of the daycare centre annex in the old town of Kuressaare was determined first and foremost by the historically settled urban context into which we humbly tried to fit the new building. If you are asking whether limestone was the conceptual starting point for the design process, then actually, we moved in the opposite direction—from the level of an urban design idea to the material. The limestone wall rounds the building complex off.

In the old town of Kuressaare, yards play almost as important a role as buildings. We shifted the placement of volumes determined by the construction area and stretched the new building part to the edge of the plot. This resulted in a sunny and wind-sheltered yard amidst the daycare centre, which can be used in nice weather for indoor activities, and which you can enter also directly from the street. Kuressaare has very little of the dense urban space that characterises Tallinn Old Town, where buildings are packed tightly together; rather, the street space dimension here is held together by stone fences on the edges of plots, often cobbled together from limestone. With our limestone wall, we paid respect to a stone fence which we quite rudely ploughed into with the façade of our new building. We borrowed the idea of a hip-roof shaped end wall from the buildings at Tolli street that have side façades of the same shape.

Is limestone masonry merely a heritage thing or does it have untapped potential also for contemporary architecture?

In molumba, we seek to involve original material strata in our projects, but we do not directly take over traditional techniques or materials in the design process. Instead of copying these things one-to-one or engaging in renovation, the important thing is to create contrasts. This helps to clearly distinguish and value what has been and what is now. It is easy to go on about how people in the olden days really knew their business and how the quality of construction was something else. Of course we would like to build only with logs that have been harvested at a proper time and limestone that has been quarried locally, but you have to stay pragmatic when building with the tiny coronavirus relief funds designated for the elderly in Saaremaa Municipality—most of the old material-based techniques, which often relied on skilled craftsmanship, are too labour-intensive and expensive for the modern public procurement system, which is why they can be applied only partially. Even then, they need to be tagged as conceptually vital so that no one would dare to cross them out.

Who was it, then, who ultimately built that wall?

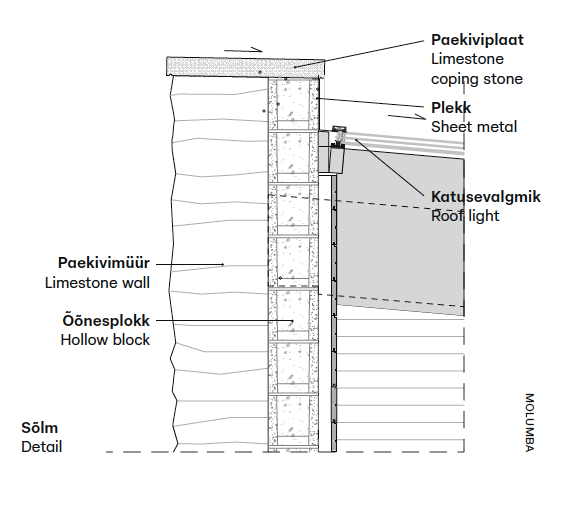

The wall was laid by local stonemasons. Although the result turned out well, we had a long argument over the rendered base of the building. In our view, the end result loses the initial illusion that made it seem as if the building grew out of the stone fence. And yet, the craftsmen were indeed laying a wall for a building, whereas a stone fence would have required a different kind of solution. The masons knew this from their experience, and it was careless of us not to draw out this node in a clear way. As we tried to take these sorts of technical nuances and specialised skills into account, we found ourselves making decisions that went against the initial concept, e.g., to use dry stone for the fence in order to preserve the original appearance, and distinguish it clearly from the new part which required lime-mortar masonry to stop the spread of humidity.

Johan Tali, architect

TONDIRABA PARK

Architecture: Artes Terrae

Engineering: Klamber OÜ, Roadplan OÜ

Area: 27 ha

Function: public park

Built in: 2021

Location: Tallinn, Eesti

Cost: € 9 000 000

Client: Tallinn Urban Environment and Public Works Department

Photos: Heiki Kalberg

In what form does limestone figure in the park? Does it play any role in determining the park’s character?

The entire district of Lasnamäe was built on limestone, and limestone forms a significant part of the environment there. When we went to Tondiraba for the first time, we were enchanted by the wild look of the place. There was once a natural environment there–a bog and limestone outcrops–but then, after Lasnamäe was built, Tondiraba was used for disposing of concrete waste. The place was subsequently forgotten for several decades and could mature and self-organise on its own. Our task as landscape architects was to clear the valuable parts from the mess that had developed. In the course of diligent clearing out it turned out that in addition to peat, wasteland, forest and waterholes, one important component of the park is also limestone. It occurs in the park in the form an outcropping by the parkside road as well as a plateau in the very centre.

Limestone and peat have an equally important role to play in the park. Limestone is strong and firm, peat is soft and swaying. There are places in the park where you are standing on four metres of peat, but only a couple of steps away, there is a limestone outcropping and the face of the park is suddenly completely different. Limestone gives an atmosphere and tonality to the park. Thanks to limestone, there are several waterholes in Tondiraba. In one case, the limestone keeps water from seeping into the ground; in another, the waterhole developed in the depression from which limestone was once quarried.

In the course of building playgrounds, some limestone had to be excavated. However, all of it was reused in the park. Some of the stepping stones for crossing a ditch, for example, are made of limestone. Limestone was piled near the habitats of lizards so they could warm themselves on the stone and hide in the cracks. Limestone was also used for decorating new green islands in the cafe area of the park. Limestone from the park was also embedded into the design of the mountain bike trail.

What do you mean by clearing the limestone cropping in the park?

From the heart of the park, we found a limestone plateau—basically, a floor made of natural stone. Usually, limestone gets covered with vegetation, resulting in species-rich alvars, which used to stretch also from Lasnamäe to Pirita. In Tondiraba park, however, the limestone lied bare. Scraggy, but all the more exciting plants were only present in the limestone cracks. We were immediately charmed by this open space. In the course of construction works, it was not tampered with any further than cleaning the top surface of the dirt that had accumulated there. This revealed a light grey limestone, while the microcosm of life within the cracks was left intact.

There was plenty of thought put into how to protect the fragile environment during the construction works. On the one hand, the hard limestone surface provided a good place for storing building materials; on the other hand, the ecological communities there were very important to us—it would be impossible to achieve anything like them simply with planting anew. The most fragile spots were marked as a no-build zone. Just before the park was opened, the builders brushed the limestone plateau once more. The plateau became the centre of the park, a meeting ground of nature and people.

Merle Karro-Kalberg, landscape architect

MOONSUND HOUSE

Interior architecture: Hanna Karits

Architecture: Happy Home

Area: 250 m2

Function: rural house

Built in: 2022

Location: Moonsund archipelago, Estonia

Client: private owner

Photos: Tõnu Tunnel

Why did you decide to use limestone in the Moonsund project?

It began with our decision to use a lot of wood in the project at the request of the client. I chose thermally treated ash wood for the purpose, whose warmth and heaviness needed a balancing material to go with it—something cold and robust by nature. I planned to use wood for many different extra-precise details, such as handles and thin slats, profiled boards and their endings. This wealth of detail likewise required something more archaic by its side.

In rural houses, I have set myself the task of achieving a symbiosis of the historical and the modern. Use of limestone creates a sense of timelessness, and there is a lot of this stone on islands. For the Moonsund house, I chose to use Lasnamäe limestone, whose tonality and other properties worked very well with this object. I knew its wear-and-tear characteristics and durability, especially when used in surfaces that see a lot of movement. It is also important to know the client—some are pleased with the material changing over time, while others are very much not. I myself am especially fond of how natural materials change—how they age in a dignified manner and how paths are worn into them after a long period of time. Even if natural materials get scratched, you will not see some other material layer underneath. It is the same both on the inside and outside.

What properties of limestone would you highlight as opportunities and/or complications for interior architecture?

I always emphasise with regard to natural stone that there needs to be a natural stone specialist on site. The craftsman also needs to have a good eye—he needs to be able to follow the patterns of the stone and tonality of the pieces. I draw all the details in a very precise manner, but even if it is all millimetre-by-millimetre on the paper, what counts at the end of the day is whether the craftsman is able to actually piece it together in this way. In the case of this particular project, everyone was invested in achieving a good result. This was in a way facilitated by the fact that the site was remote and people stayed there for longer. Thus, for instance, the solution for the back wall of the kitchen was born on-site. I saw some stone offcuts and we decided to cover the wall with them. Narrow limestone slabs gave the wall a rhythm very different from the rest. The material is the same as elsewhere, but its effect is much more refined.

When we create order in architecture, we also need to find disorder within it. I have discovered that natural stone invites you to follow its patterns. These patterns have not been created by humans, but have naturally emerged. You can look at natural stone over the years and keep finding new aspects of its pattern. This has an interesting effect on the brain. For instance, some limestone pieces have very splendid fossils in them. This reminds me of another nuance. Surface finishing is very important with natural stone—it is one thing when polished, and something completely different when sanded or flamed. Polished surface, which is the most common one, strikes me as suffocatingly luxurious, whereas sanded surface looks much more natural, velvety and soft.

Is the local origin of the material important to you?

For now, I do not want to limit myself to choosing only materials that are available here at home. But it is also the case that after you open a certain door—say, start working with local limestone and get to know it—then you will find very many other opportunities for using it. It is the same as with inspiration—you just need to work, and then it will come.

Hanna Karits, interior architect

RECONSTRUCTION OF THE NATIONAL LIBRARY

Design: Sirkel & Mall

Contractor: Ehitus5ECO

Area: 45 000 m2

Function: library

Built in: 2022–…

Location: Tallinn, Eesti

Cost: ca € 90 000 000

Client: Riigi Kinnisvara

Does the extensive use of limestone in the National Library building pose an additional complication when renovating?

The works to be done were known beforehand, so limestone presented no additional complications. The only difference from usual façade works is that limestone should not be worked on in late-autumn and winter conditions, so this should be taken into account when planning work. In the late autumn and winter, we worked on the limestone walls inside the building.

It has been 30 years since the National Library was built. How has the material withstood the test of time?

The façades were in a fair condition. In some places where water had run through the roof and parapet, the situation was somewhat worse, but even these parts could be repaired. The interior was in a better shape. We used intact old stones from the new openings that we created to seal up and replace parts of the façade. The limestone in the amphitheatre walls was replaced in full because the base structures needed additional reinforcement. We sorted out better bits of limestone from what we had torn down, and these could also be used for repairing the façade and older walls within the building. In balustrades, however, only about 70% of the old material could be preserved. The rest of balustrades had to be built with new material. Overall, the project did not add a significant amount of new limestone, but consisted rather in extending certain walls or making them taller. Limestone is now more visible in the interior, however.

What prospects do you see for similar uses of limestone in contemporary buildings?

Personally, I do not believe that future buildings will be using limestone in such large quantities as in the National Library building. The main reason is that working with limestone is labour-intensive, time-consuming and seasonal, and high-quality limestone products are scarce. Admittedly, architects have never found these arguments decisive, and never will. Smaller volumes of limestone will surely be used in buildings also in the future, because it is a good and nice material, and also happens to be our national stone. If the name given to a building includes the word ‘national’, then it is likely that limestone will find some place there.

Priit Õunapuu, construction project manager

VANA-KALAMAJA STREET

Architecture: Kavakava

Project: K-Projekt

Lenght: 1,1 km

Function: tänavaruum

Competition: 2017

Built in: 2022–2023

Location: Tallinn, Eesti

Cost: € 10 000 000

Client: Tallinna Urban Environment and Public Works Department

What is the difference between paving the streets with natural stone, concrete (pavers), asphalt or something else?

In a city where the main issue is still whether the streets are passable at all, the material used in paving does not seem much of a priority for pedestrians. But perhaps this is precisely why the choice of material sends such a strong signal, indicating a certain attitude towards the users. In Kavakava, we are of the school of thought according to which every material has its place and no single material should be idealised at the expense of others. For example, if there would not be all this excessive asphalt around us, then asphalt would seem as an absolutely brilliant dream material. Without any natural stone, however, it is hard to achieve a beautiful paving—stone introduces texture, colour and everything that makes a surface come alive. Natural stone has the advantage of everlasting durability and reusability. Since natural stone is more expensive than other materials, it also provides a simple way of indicating the importance of the place or showing your respect toward the user.

How do you take the origin of (paving) materials into account when choosing them?

In case of paving, we have never thought of using any exotic materials, because the ground surface has a particularly close connection with the nature of a place. The choice is between concrete, asphalt, brick, and (in case of sufficient funds) granite—materials that are theoretically available in the vicinity. In practice, though, the architect has currently no leverage to decide the geographic origin of the material. Our reference granite might have been from Kuru quarry in Finland, but if the contractor is able to find sufficiently similar stone from China, then this is where it will come from.

Could or should paving be symbolically significant or unique to a city?

No paving typical to Tallinn has developed. The first widely used type of pedestrian road in the outskirts was made of 1 × 1.5 arshin-sized limestone slabs (71 × 107 cm) that were laid between cobble stones. An advanced version of a similar paving is still prevalent in Copenhagen, for instance. Given that they use durable granite in Copenhagen, they have continued to pave the streets following the same principle, and in its modest way, this is indeed something that is deeply associated with Copenhagen. The limestone slabs that were used in Tallinn were more fragile and got replaced with asphalt, so no typical kind of paving has spontaneously developed. Limestone is not a good paving stone by nature. Good paving stone is one that can be used again and again for hundreds of years, like the cobble stones in the Old Town—just tear them up and put them back down. We placed a sample limestone slab on Vana-Kalamaja Street, which Kalamaja Museum guides can go to and use it tell stories about the history of paving in Tallinn. There we can also observe how limestone will fare, and unless someone accidentally sprinkles salt on it, it should last a while.

Paving being unique does not necessarily mean that it is fancy and striking in the way of the famous black-and-white stone patterns of Lisbon. Uniqueness might also consist in nuance—for example, in the squares on Vana-Kalamaja street, we treated the surface of natural stone by chipping it, drawing inspiration from the hand-chipped slabs under the arcade of the Town Hall. Nowadays, the chipping is done with machines, but the result is nevertheless much richer in nuance and pleasantly rougher than the usual flamed surface.

Siiri Vallner, architect

HEADER: Kuressaare Daycare Centre Annexe, molumba. Photo: Tõnu Tunnel

PUBLISHED: MAJA 1-2024 (115) with main topic STONE