Planning in Norway is strongly guided by strategic approaches and broad state-set goals directing the local level. This is also reflected in the management and development of local cultural heritage. Vignir Freyr Helgason, senior advisor at the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage (Riksantikvaren) gives an overview of how strategies are developed and implemented in collaboration between the state, municipalities and communities.

Complex contemporary challenges across Europe have, over time, called for a shift in the way we approach planning. In Norway, as well as many other European countries, urban planning practices are largely project-based and initiated by private actors. This has called for a strategic approach in planning and development as well as heritage management. In order to help maintain urban cultural heritage, the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage (Riksantikvaren) published a combined strategy and policy for management of urban heritage in 2017.1 A revised strategy was published in 2021 in response to the new Cultural Heritage policy from the Norwegian Parliament.2 The new strategy describes how cultural environments are an important resource for developing sustainable cities and places. At the same time, it signalises the Directorate’s policy of planning and building cases related to the management and development of cultural environments. In what follows, I will explain the need for this kind of strategic approach, and how cultural environments can and should be seen as integrated parts of planning and development.

What are cultural environments and how are they managed in Norway?

The Norwegian Cultural Heritage Act of 1978 introduces the term ‘cultural environment’ and defines it as an area of cultural-historical value where cultural monuments are part of a larger whole or context. Since then, the term has acquired an even broader meaning. A new report on the cultural heritage field addressed to the Norwegian Parliament establishes ‘cultural environment’ as a collective term for cultural monuments, cultural environments, and landscapes.3 The report is a so-called white paper that describes the work carried out in a particular field and its future policy. The revised Strategy for Management of Norwegian Urban Heritage, launched by Riksantikvaren in 2021, explains how a cultural environment can include both built and natural elements. It also describes how cultural environments affect our experience of belonging and well-being, and how they relate to the social aspects of sustainability. This signalises a change in how heritage is defined and managed—a shift from focusing on singular objects to focusing on larger environments and how the experiential values of heritage are relevant to both users and managers of a heritage site.

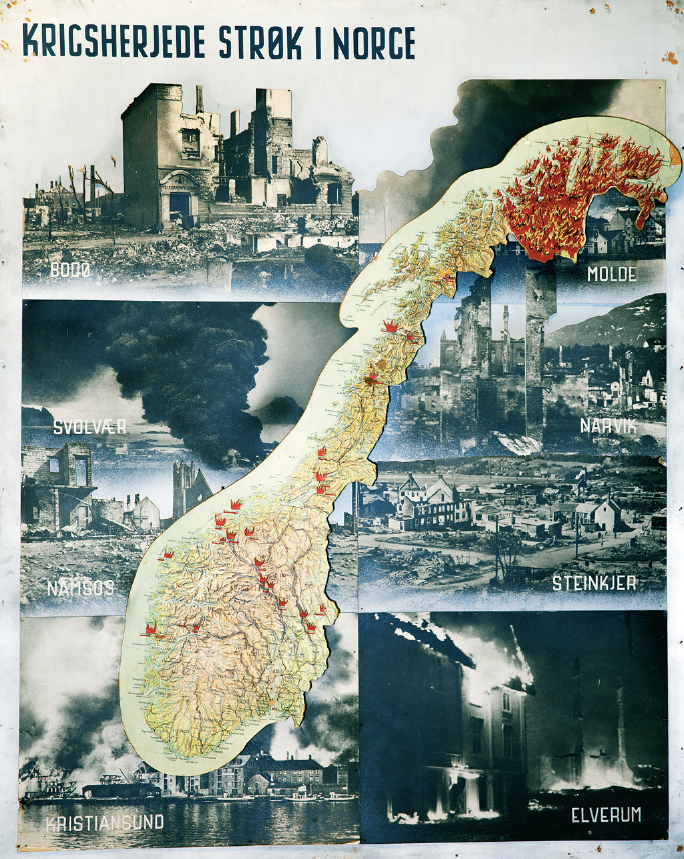

In 2006, Riksantikvaren introduced the ‘NB!-registry’, a knowledge base with overviews of over a couple of hundred cultural environments of national interest.4 Many of the identified cultural environments of national interest carry stories and knowledge-, experience- and use-values. One example consists in the many reconstructed cities that tell the nation’s post-war history following the bombings and fires of World War II. Another example would be the wooden houses along the southern coast of Norway, which have historical connections to the sailing ship era that lasted from the 1400s to the early 1900s. These places have a distinctive character and convey both knowledge and experiences of life in the past. Municipalities have a central role in ensuring that the heritage values of these areas are maintained in the face of development processes, whilst regional and national levels of cultural heritage management have the possibility to object to planning proposals that are in conflict with regional and national interests.

The need for new approaches to urban cultural heritage management

A principal change in planning processes occurred in the 1980s, when development became neoliberal, project-based and developer-initiated. At the same time, the role of government and public administration changed from being a planning authority to being a managing authority. In Riksantikvaren’s view, this situation called for a new approach to managing urban heritage.

Strategic planning has emerged in recent decades as a tool to meet complex challenges in European planning. Strategic planning differs from traditional planning forms in being more flexible and open to influence by other actors. Whilst a traditional plan often presents expert solutions to previously defined problems, a strategic plan puts forth a vision with a course of direction that can deal with future uncertainties. This change in planning is visible in the Norwegian context in the Planning and Building Act of 2008, which introduced planning strategies and area regulation as new planning forms.5

Strategic planning is often characterised by broad and inclusive visions, which are often difficult to translate and put into practice. In Norway, there is a strong culture of local governance in the municipalities, and the challenge for the state is to stimulate regional and local involvement without taking control and to get different actors committed and involved.6 At the same time, Norway has international obligations stemming from agreements such as the European Landscape Convention of the Council of Europe and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. A need has emerged for strategies from the government side that would outline the challenges and give recommendations to the regional and local governments in the municipalities on how to achieve these goals.

Since the 1990s, cultural heritage management authorities in Norway have focused on developing tools to cope with this new context of planning, as well as on contributing to capacity and network building. This involves establishing networks like the Forum for Place Development (Forum for stedsutvikling) that bridge different sectors in planning. The Forum was established by the Norwegian Ministry of Environment in 2006 and has since focused on sharing knowledge across sectors and different levels of planning at regional and national conferences. Riksantikvaren has also financed value creation projects within the heritage field that stimulate development of local businesses and inspire knowledge sharing.

Strategies and tools for sustainable management of Norwegian cultural environments

Several strategies have been published by the Directorate over the last couple of decades dealing with different areas of cultural heritage management in Norway as well as collaborations abroad. The Strategy for Management of Norwegian Urban Cultural Heritage differs from the others in that it functions as a policy linked to the management of more than a couple of hundred cultural heritage environments of national interest in cities and towns found in the NB!-registry. The combination of the registry and strategy has helped to focus on these areas as important in municipal planning.

Densification is a topic that has been given a central place in Riksantikvaren’s strategies. This is because compact urban development has been highlighted as an important climate measure in state-level planning guidelines and expectations for planning.7 However, in some cases densification is not compatible with sustainable management and development of cultural environments. Urban transformation often involves extensive redevelopment and renewal, while urban regeneration is principally based on developing the existing context and place qualities.8 Reuse is a common principle in Riksantikvaren’s Climate Strategy for Cultural Environment Management (2021) and the new Strategy for Management of Norwegian Urban Cultural Heritage (2021). Preserving and reusing existing buildings and urban environments is important for the experience of place identity and the perception of belonging in general. It is also advised that new buildings adapt to the existing environment to strengthen the values of the cultural environment.

In the face of the challenges mentioned above, Riksantikvaren’s revised Strategy for Management of Norwegian Urban Cultural Heritage has gathered tools and recommendations on how cultural environment values can be safeguarded in the course of development. One of the main tools for cultural heritage management in Norwegian planning is the Cultural Heritage Plan. Such plans are an important tool for municipalities and counties for gathering knowledge and getting an overview of cultural monuments and sites of local, regional and potentially national interest. Thus, Riksantikvaren has since 2011 had a strategic focus on helping the municipalities (in collaboration with the counties) to build up systematic knowledge using Cultural Heritage Plans as a tool in local planning.9

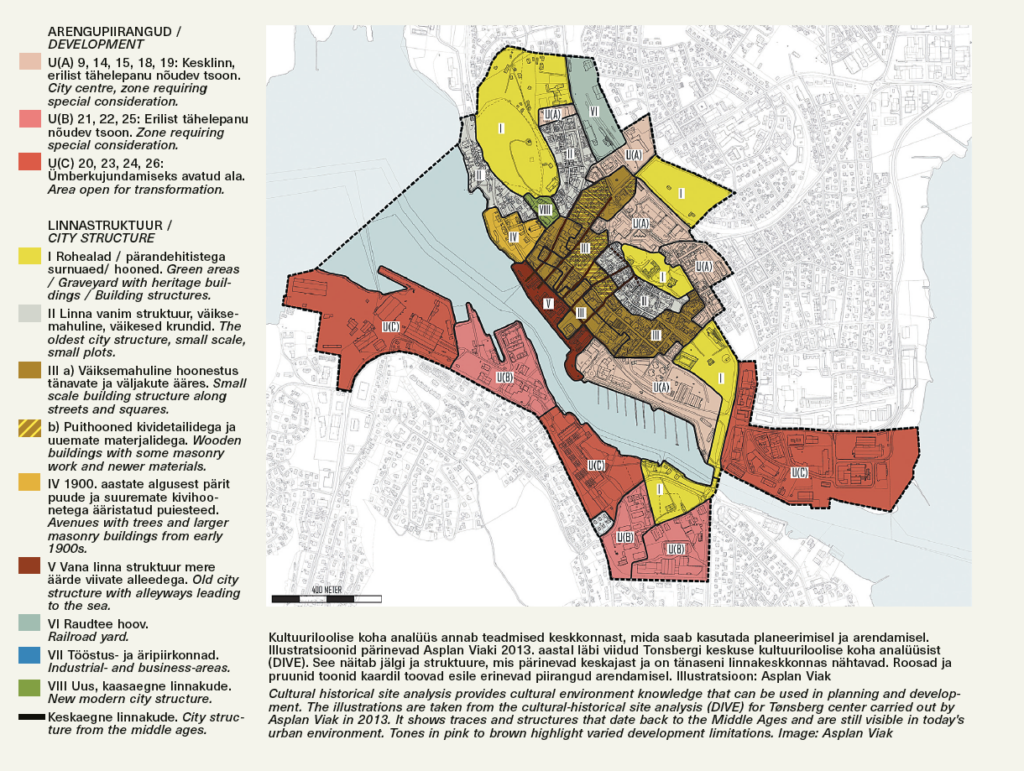

One way to gather knowledge is to carry out urban cultural heritage/place analyses by using Riksantikvaren’s DIVE Urban Heritage Analysis.10 The method is divided in four steps—describing, interpreting, evaluating and enabling. The core idea is to involve local communities in all the steps—in gathering knowledge about the history of cultural environments, evaluating it and using it in local planning and development. The method has been important in places like the Norwegian town of Tønsberg, where the outcome of such analysis is actively used to inform planning decisions today. In 2020, this kind of analysis was also carried out for Midtbyen borough in Trondheim, where private and public actors participated in the work of ascertaining conservation values and clarifying the scope for development in the district.11 The report constitutes an important knowledge base for further planning of the cultural environment.

Existing knowledge may be accessed and used for both publicly and privately initiated planning proposals. The Directorate puts emphasis on sharing knowledge with both private and public sectors through online databases such as Askeladden.ra.no (for actors that deal with cultural heritage management) and Kulturminnesok.no (for the public). The NB!-registry mentioned above is integrated in both solutions.

The strategy emphasises that cultural environments can be planned and developed in ways that either strengthen or weaken heritage values associated with social, environmental, and economic dimensions of sustainability. The culminated experiences that are described in the new strategy and the tools mentioned above show that knowledge about cultural environments and the values that they consist of is important to ensure their sustainable development.

Building and sharing knowledge is important

Demands for efficiency and simplification of cultural heritage management in Norway have led to many tasks within cultural heritage management being transferred from Riksantikvaren to the counties. At the same time, the new white paper on cultural heritage policy (from 2020) sets ambitious goals that revolve around the social aspects of sustainability. One of these goals states that ‘everyone shall have the opportunity to get involved in and assume responsibility for the cultural environment’. This goal is similar to the ideas in the European Landscape Convention of the Council of Europe, which actively promotes involvement of communities in planning and development. The same convention acknowledges built and natural landscapes as an important quality in people’s lives. This broad approach to landscape as well as the emphasis on participation, all the while having fewer resources in the public sector, has influenced the way Riksantikvaren approaches the work with urban heritage. This has resulted in new working methods and a reconsideration of how to utilise resources, including an emphasis on knowledge building and collaboration across planning and development sectors and management levels to get good results.

After various reforms, Norwegian municipalities have been given a greater responsibility for cultural heritage and they are now one of the most important actors in planning. Therein lies also a possibility to use cultural heritage in planning strategically to support the attractiveness and liveability of cities and places. To do this, it is vital to build up, use and share knowledge across different sectors and private and public actors. Key actors in management of cultural heritage who are often overlooked are the owners themselves (both public and private), and voluntary organisations that work on building and sharing knowledge as well as monitoring and influencing the development of cultural environments.

Using cultural environments as a premise in planning and development means being aware of the social, economic, climatic and environmental aspects of development that the cultural environments are a part of. It is often said that cultural environments are a common good, and that it is a shared responsibility and opportunity to take care of them. As described above, there are many ways to access or develop knowledge about cultural environments—the difficult part is to make different actors aware of these ways and use them in planning. Based on my own experiences with management of cultural environments of national interest in Norway, I find that successful are those who understand this shared responsibility for the management and sustainable development of cultural environments.

VIGNIR FREYR HELGASON is an Icelandic-Norwegian architect who has been working as a senior advisor at the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage (Riksantikvaren) since 2018. He is currently also a PhD student at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design (AHO).

HEADER: Piers in Trondheim. Use of environment has changed over time and new buildings have adapted to the existing surroundings, which provides historical continuity. Photo by Lene Buskoven, Riksantikvaren

PUBLISHED: Maja 109-110 (summer-autumn 2022) with main topic Built Heritage and Modern Times

1 Riksantikvaren. ‘Strategy for management of Norwegian urban cultural heritage 2017-2020’. (Riksantikvaren, 2017). https://ra.brage.unit.no/ra-xmlui/handle/11250/2568021

2 Riksantikvaren. ‘Riksantikvarens strategi og faglige anbefalinger for by- og stedsutvikling’. (Riksantikvaren, 2021). https://ra.brage.unit.no/ra-xmlui/handle/11250/2827016

3 Ministry of Climate and Environment. ‘New goals for Norway’s cultural environment policy—Meld. St. 16 (2019–2020) Report to the Storting [white paper]’. (Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2020). https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/meld.-st.-16-20192020/id2697781/

4 Riksantikvaren. ‘NB!-registeret’. (Riksantikvaren, December 14, 2021). https://www.riksantikvaren.no/prosjekter/nbregisteret-kulturmiljoer-av-nasjonal-interesse-i-byer-og-tettsteder/

5 Toril Ringholm og Hege Hofstad ‘Strategisk vending i planleggingen?’ [chapter] in Gro Sandkjær Hanssen & Nils Aarsæther [book]. ‘Plan- og bygningsloven 2008: En lov for vår tid?’ (Universitetsforlaget, 2018), pp. 109-110

6 Toril Ringholm og Hege Hofstad ‘Strategisk vending i planleggingen?’ [chapter] in Gro Sandkjær Hanssen & Nils Aarsæther [book]. ‘Plan- og bygningsloven 2008: En lov for vår tid?’ (Universitetsforlaget, 2018), pp. 121

7 Kommunal- og moderniseringsdepartementet. ‘Nasjonale forventninger til regional og kommunal planlegging 2019 https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/cc2c53c65af24b8ea560c0156d885703/nasjonale-forventninger-2019-bm.pdf

8 Vignir Freyr Helgason, ‘Transformasjon og byomdannelse – ulike planprinsipper for vern og utvikling av industrimiljøer i København og Oslo’. (ArkN, 2021-3), pp. 104–113.

9 Simen Pedersen, Kaja Høiseth-Gilje, Sigrid M. Hernes and Bjørn Ingeberg Fesche. ‘Evaluering av satsingen Kulturminner i kommunene (KIK) – erfaringer fra kommunene’ [report]. (Menon Economics, 2020). https://ra.brage.unit.no/ra-xmlui/handle/11250/2683672, pp. 3

10 Riksantikvaren. ‘Urban heritage analysis. A handbook about DIVE’. (Riksantikvaren, 2010). https://ra.brage.unit.no/ra-xmlui/handle/11250/176994

11 Trondheim kommune and Asplan Viak. ‘FramtidsTrondheim—DIVE-analyse av nordøstre kvadrant’. (Trondheim kommune, 2020) https://sites.google.com/trondheim.kommune.no/framtidstrondheim/plan-for-sentrumsutvikling/omr%C3%A5deplan-for-nord%C3%B8stre-kvadrant-i-midtbyen/dive-analyse-nord%C3%B8stre-kvadrant