The stories we have heard ever since the beginning of the century about the merchandising of museums and the transformation of all culture into an unending festival are greatly exaggerated. The new cultural buildings are good examples of state-commissioned public spaces that are quite self-aware with no desire to go along with the general trends of commercialisation.

The design and construction of cultural buildings in the past thirty years have been accompanied by media scrutiny and disagreements, with public opinions voiced on the budget, architecture as well as locations. Also the rhetorical dimension is a characteristic feature—the national conservative conviction that Estonians as a nation of culture deserve the given buildings is heard alongside the new liberal doubts whether we can really afford them all. Culture was infamously equated with concrete,1 as the basic infrastructure in the form of concert halls or museums had remained unbuilt in the course of the entire 20th century.

These are without doubt highly important public structures shaping the urban space, functioning as symbolic landmarks as well as moulding the users to consume culture precisely in this kind of environment. Namely consumption is the keyword to be used when speaking about the culture of the period. Reduction to consumers and services no longer designates only the relations governing shopping centres, it has permeated to our public spaces and today nobody frowns upon discussing exhibitions or concerts as well-packaged experiential products. A unique space forms an integral part of the given experience whether in a new-build or a rejuvenated old building.

The commercialisation of culture is also related to the more general issue of the boundaries of culture in the age of symbolic capital—an art gallery in a shopping centre does not turn the centre into a museum but nevertheless allows to enrich the overall product selection. The activity centres gaining ground in various corners of Estonia from the Windtower on Hiiumaa island to the Pilgrims’ House in Vastseliina from the past decade are all hybrid experiential spaces that have become full-fledged local sightseeing objects by transforming culture into an easily digestible form. Opened opposite the National Opera Theatre in Tallinn in 2009, Solaris Centre had been marketed as a versatile building for cultural and leisure activities with retail business playing only a supportive role in an attempt to alleviate the tensions accompanying the design process.2 Even if the scales in Solaris today are tipping the balance to business, it marked a symbolic shift in the general understanding of the autonomy of culture. In 1990s, nobody questioned whether museums, libraries or concert halls were to be separate places for creating culture, however, now that the dough has leavened and things are far less straightforward, culture is just like any other pastime.

Whether our age is called the attention economy or something else, the trend in spatial development includes clustering and bringing various experiences and leisure activities together into one place thus mitigating risks and making people spend more time at their place. A café, restaurant, educational spaces, playrooms, auditoria and outdoor areas—all these accessories define the contemporary cultural institution just as much as its location in a glammed-up zone of former docklands or in a peaceful corner of a park.

New cultural centres

Relatively few new cultural objects in the strict sense of the word, that is, new buildings for collecting, researching, performing or exhibiting professional culture have been built during the independence years.

There are five completely new museum buildings, listed here in descending order of size: Estonian National Museum (2016), Kumu Art Museum (2006), Film Museum of the Estonian History Museum (2017, part of Maarjamäe Palace), Vabamu (2003) and Palamuse Parish Museum (2018, actually its new exhibition hall).

Completely renovated museums are considerably more numerous: the Seaplane Harbour and Fat Margaret of the Estonian Maritime Museum, the Great Guild Hall of the Estonian History Museum, the Storehouse of Pärnu Museum as well as the castles in Narva and Haapsalu.

The only private art collection museum in Estonia in Viinistu got an elegant extension to its existing building in 2012.

Almost all museums have undergone less extensive renovations with new permanent exhibitions added. A considerable role has been played by the EU funding: in 2004–2011, altogether 29 museum developments were financed (including the Science Centre AHHAA and the outdoor area of the Estonian Road Museum), similarly the few dozen visitor centres mentioned above. Thus, most museums are located in historical buildings which is no doubt a worthy function for buildings of great heritage value but at the same time it also shapes the general understanding of the nature of museum spaces while also limiting the developmental needs that the institutions would actually require.

Two new concert halls have been completed—in Pärnu (2002) and in Jõhvi (2005) with the latter including a large-scale reconstruction of the former cultural centre. A concert hall was added to the Solaris Centre in Tallinn which is barely visible next to the shopping centre, also the Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre was given a new high-quality hall.

Arvo Pärt Centre in Laulasmaa (2018) is similarly related to concerts and music bringing together the functions of a concert hall, archive and visitor centre.

The construction of new modern libraries has also halted at two—Pärnu Central Library (2003) and Pääsküla Library in Tallinn (2005). With the dense library network originating from the Soviet era as well as the monumental National Library completed on the threshold of the new era, there was actually no great need for new libraries.

The list ends here as far as new-builds are concerned. In terms of real estate, theatres were in the best condition after the re-establishment of independence—all main cities had completed the construction of their theatres in the 20th century with only minor modernisation required later. The innovation in early 1990s was the black box, a context-free zero space that could be constructed in any room. There have been no completely new theatre buildings, as also the buildings of Vaba Lava theatre in Tallinn and Narva are actually large-scale reconstructions of earlier buildings. On the other hand, for years there have been discussions on the need for a new opera theatre.

Culture also includes cinema that seems to be the only cultural institution not affected by the so-called market failure and all new cinema buildings have been developed by the private sector, always with several auditoria and usually as a part of a larger commercial structure.

Thus, altogether around ten state-funded new-builds and a large number of revamped environments that—excluding the National Museum, Seaplane Harbour and Kumu Art Museum—are not large enough to talk about the hybridization of culture and commerce or a new type of consumption of culture on a large megastructural scale. Then again, the understanding of the position of culture in the society has undergone major changes in the given years, there have been alterations in the audience as well as in their expectations with also fragmentations in the institutional field of culture. Space is bound to keep abreast with the changes, shaping or actually reinforcing the identity of its users—the aforementioned consumers of culture. Looking at works of art in Kumu halls with white walls feels quite different from doing it at the Contemporary Art Museum of Estonia in the deliberately unrenovated former heating plant in Tallinn. In addition to their users, buildings also shape the institution’s identity by reflecting the institutional hierarchy and the operating logic of presenting culture—the kind of spaces needed for the particular purposes. For instance, museums require offices, proper storage solutions, exhibition halls with specific requirements and effective visitor areas, concert halls need facilities with top-quality acoustic features, rehearsal rooms, walking area etc. Concert halls are the bastions of classical music, it would be unthinkable to have a discotheque here. Libraries generally require silence and serious atmosphere with spacious reading rooms, and in this respect, the National Library (architect Raine Karp, designed in 1985) opened in 1993 could be regarded as our most temple-like cultural building.

What kind of audiences are created by the new cultural buildings, what is the message carried by their spaces? To what extent are the buildings reflective of the changed understanding of culture, will they bring the high and distant arts nearer to us?

The competing self-images of museums

I will take a closer look at museum buildings as these have been the most numerous among the completed cultural buildings, with their image taken the greatest developmental leaps during the independence years by becoming increasingly audience-friendly. It is also reflected in the rise in quality: until the independence years (actually up to early 21st century) all major Estonian museums operated in buildings adjusted for the given purpose.3 At the beginning of the new century, the places that had mainly been associated with dust and frozen time became crowd-pullers, educational centres and venues where also space provided a special experience.

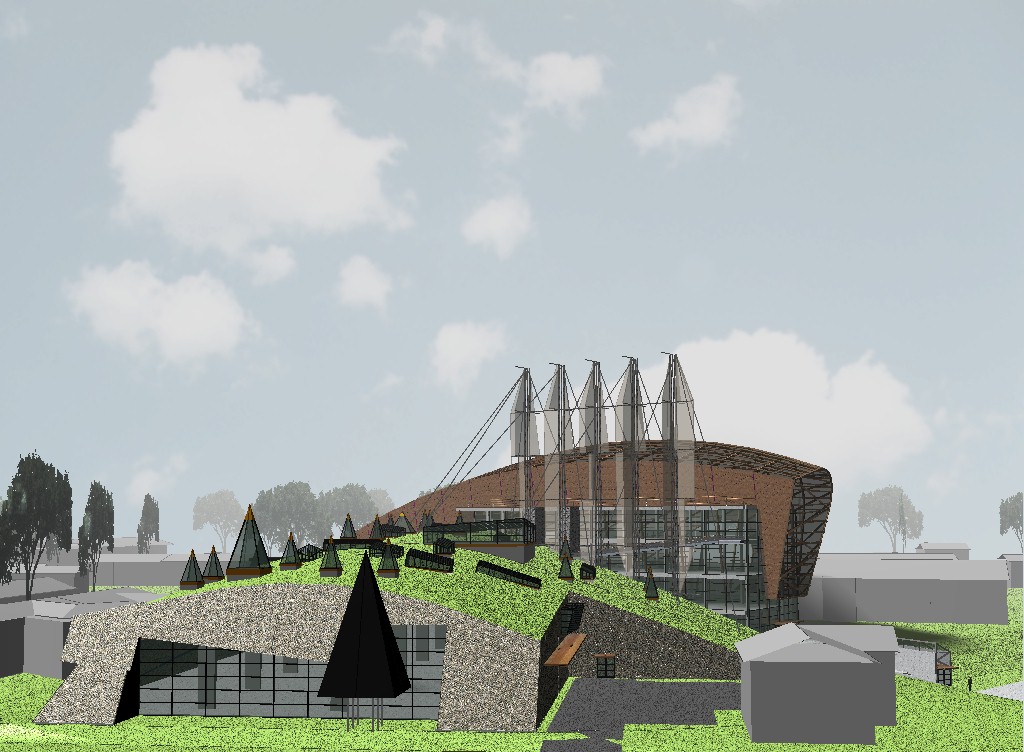

The architecture competitions for the new building of the National Museum (ERM) in 1993 and Estonian Art Museum in 1994 were the first time when architects, specialists and the society at large could explore the idea of a contemporary museum. Another sign of the time is that no more cultural buildings were designed in 1990s as there was neither money nor readiness—culture as the engine of urban innovation and the attractiveness of creative economy became hot topics only in the new century. As the wait had been long and the newly regained independence demanded new symbols, both buildings were to become national monuments and shrines of culture. ERM was initially meant to be located in the centre of Tartu on Toomemäe Hill, with the explanatory statement of the winning entry by Tanel Tuhal and Ra Luhse making a straightforward declaration: it is a monument to Estonians featuring our history, spirit and character, and the Estonian nationalism must be recognisable to all visitors. The given Estonian nationalism obviously had to be invented yet, there were plenty of illustrative features: the turf roof above the exhibition hall for growing crop and making Midsummer bonfires, taller jagged volumes signifying the foreign invasions, interiors with white floors, black stairs and blue-sky ceilings… In terms of space, it still represented the previous decade’s understanding of museums as institutions collecting and researching artefacts, with most of the layout taken up by storage spaces and exhibition halls (the permanent exhibition was called ‘research exposition’), a miniature place on the second floor for a shop or a café and no educational areas. As times were tough, the building extending over 23,000 m2 was obviously never constructed.

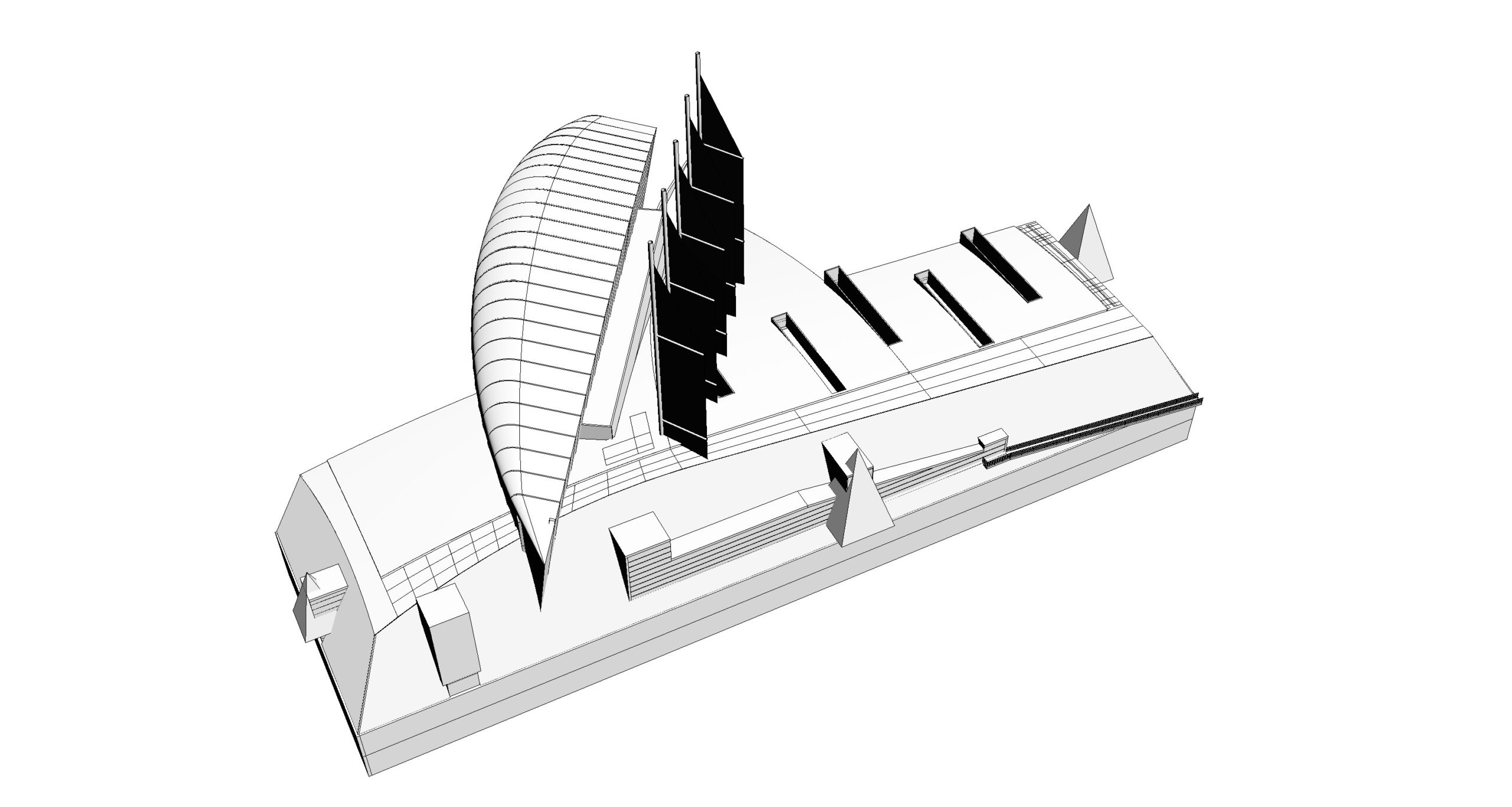

There was an international competition for the somewhat smaller building of the Art Museum with a remarkable number of entries (233), and differently from ERM in Tartu, the location in Tallinn was farther away from the city centre along the limestone klint in Kadriorg. The given competition entries included practically no elements of national myth creation, instead, a neomodernist approach prevailed to a greater or lesser extent interpreting abstract geometry that has come to be seen as an example of the simultaneous existence of various architectural paradigms during the transitional period.4 The building dubbed Kumu after its opening (architect Pekka Vapaavuori, completed in 2006) is indisputably monumental in its geometry and featuring Modernist seclusion—the curve visible only from above cutting into the limestone klint and the terraced courtyard slowly make the arrival at the building more festive.

The architecture of the building leaves no doubt that the museum is a powerful institution with the size of the lobby, height of the spaces as well as the prescriptive spatial protocol for visiting the museum (entrance-wardrobe-tickets-moving around between the floors, the museum shop-cafeteria etc) reflect the mechanism of power and the guiding role of space. In our pragmatic times obsessed with profit-yielding square metres, only state-built cultural buildings seem to afford such spatial surplus, powerful distant interior views or expensive design solutions for details, thus referring to historical palaces that instilled wealth and power in their visitors. It is no coincidence that many of those palaces all over Europe have been turned into museums.

When ERM and Kumu were planned in early 1990s, for instance, there were no such burning issues as climate problems and sustainable management, and the rediscovery of empty industrial buildings as conceptually distinct spaces took almost a decade.5 However, in terms of layout, Kumu is already a contemporary museum where in addition to storage rooms and exhibition halls, an important role is also played by the logistics (through a tunnel from Laagna Road), impressive lobby area, educational facilities and workshops, an auditorium allowing additional revenue, a shop, a cafeteria and restaurant zone—true, the latter are still relatively small. However, the given richness has not been properly used in architecture as all functional units stand separate, exhibition hall visitors have no chance of spontaneous glimpses, for instance, into educational or storage areas, paths do not intersect and do not provide novel spatial experiences in the size L building. It reminds me of our neighbours’ Latvian National Museum of Art opened ten years after Kumu where observing the art collection storage space in the underground extension through safety glass was made an integral part of the visitor experience. Rem Koolhaas as the architect with the most perceptive insights into the trends of 1990s saw large scale and orchestration of chaos by diagram as a way out of the artistically and ideologically worn-out Modernism with ‘hybridizations, proximities, frictions, overlaps (…) The programmatic elements react with each other to create new events.’6

A fresh example of such orchestration is the BLOX building in Copenhagen designed by Koolhaas/OMA (2018) housing the Danish Architecture Centre with exhibition halls but also a fitness centre, penthouse apartments and a major road going directly through it, with all features effortlessly blending in with one another. A density-at-any-cost building that eventually made me feel that people did not come to see the exhibition but other people.

Our vision of the new museum architecture has naturally been more modest, with spaces keeping visitor activities separate and buildings formed as the sum of their spaces. The exception in this respect is the Museum of Occupations (now Vabamu Museum of Occupations and Freedom). The first completed building by architects Siiri Vallner and Indrek Peil only amounts to 1600 m2, however, its pavilion-like structure allows one function to transform seamlessly into another, with people sitting in the auditorium afforded views of the exhibition hall and the memorial in the courtyard while the office is overlooking the main hall. According to the authors, the aim was to create an ideologically neutral building, a so-called physical interim space that would not forbid, order or take too much care of its users.7 It is an essentially non-museum-like building with the semi-transparent glass façade and open plan vastly differing from the traditional museum spaces dictating respect. Vabamu is the first museum completed after the re-establishment of independence and built right in the heart of the capital city as a gift from the Kistler-Ritso Foundation so that the Soviet occupation of Estonia would not sink into oblivion. A quite unusual kick-off for the museum boom in the first decade of the 21st century.

The location dictating the rules

As described above, one of the greatest changes in museum work has been the explosive increase in the consumption of cultural activities that was also reflected in the spatial programme diversification and the growing number of square metres. With the necessary storage facilities (the idea of a separate common storage for various museums emerged only in the first decade of the 21st century),8 buildings grew so large that their location in the city centre seemed impossible already in 1991 when a suitable site for the Art Museum was sought in Tallinn. Paradoxically, neither Kumu nor eventually also the Estonian National Museum constructed at Raadi in the outskirts of Tartu (with the decision on the location made in 2003) could contribute to the densification of the city centre, instead, they either reinforced the existing park area (Kadriorg) or formed the basis for the emergence of a completely new centre (the former wasteland at Raadi). The museum’s location is considered the most influential factor defining its identity. For instance, Ingrid Ruudi has referred to the imagological relations of Kumu and its location: ‘In the wider urban context, it (the art museum—(T.O.) upholds the somewhat conservative vision of a public sphere where museum visits stand for an elitist Sunday pastime and the discussion is kept within prescribed limits.’9 The same conclusion was reached by Mariann Raisma in her analysis of the development of the self-image of museums in 1990s on the example of Kumu and the first ERM project: ‘A new image of the Estonian museum developed: a modern building defending the elitist content in the serenity of the park (…) Standing relatively separate from the society and postulating clear ideological messages, an elitist museum expressly represents the image of the museum as a temple or a shrine.’10 She underlines that it was not so much about the size of the available plots as the concept of the museum—a place outside one’s daily routine where you need to take the time—that relied on the vision of a bastion of high culture. Distancing as a conscious choice is also strongly evident in the identity of Arvo Pärt Centre in Laulasmaa (Nieto & Sobejano Arquitectos, 2018).

ERM’s eventual landing at Raadi in 2016, in the long-abandoned area of the former military airfield brings a new shift to the withdrawal tactics. In the meantime, the reuse of industrial and military heritage and the promotion of the majestic and the original had quickly gained ground in property development, and the Maritime Museum (KOKO Architects) opened in the Seaplane Harbour in 2012 instantly became the superstar of the local museum scenery. The experiential nature of exhibition environments was here to stay and, instead of abstract neutrality, visitors expected to be met by human scale, original stories and performance-like exposition. The winning entry of the new ERM building by Dan Dorell, Lina Ghotmeh and Tsuyoshi Tane made the only possible suggestion for the position of the museum building. They brought the focus on the runway, opened the views of the neglected and unusual landforms, the ugliness that was all of a sudden exciting and cool—primarily in the eyes of the younger generation of Estonians, not to mention the curious foreigners.

The largest of the new cultural buildings (nearly 34,000 m2), ERM is designed as a multifunctional container-type centre where you can spend an entire day. In addition to the exhibition areas, library, partly underground storage facilities (providing stable climatic conditions), offices, educational centre and museum shop, the 350-metre-long building also includes an auditorium seating 250 people, a black box theatre, restaurant and cafeteria, and a giant lobby reception area on the bridge, not to mention the outdoor area. ERM is a site revival project with theatre and conferences and the courtyard hosting rock concerts or international rally competition events. The building is designed awe-inspiringly spacious with the architectonics of the rooms and the refined minimalism of the glass façade joints reflecting both fine subtlety and somewhat sterile anonymity characteristic of non-places. Moving through the prolonged building is a slow procession, reaching all the places takes time. Visitors do not forget where they are—the exhibited ethnographic collections are not high culture in the traditional sense of the word, however, they are served on a polished platter with modern multimedia accessories and technological sophistication on the side.

With its range of subjects and wealth of supportive functions, ERM should attract the widest target group in Estonia, while the architecture of the building and its synergy with the landscape in Raadi feature subtlety that requires concentration. It is neither a Modernist box landed on the site nor conspicuous signature architecture, its spatial programme does not provide Koolhaas-like surprises. If the border areas of Tallinn and Tartu used to be marked by shopping centres and public spaces completely dominated by commerce, then ERM presents a new type of centre with culture as experience forming the core. It is a public space brought under the same roof, a hyper-museum with a lot of effort made to ensure the high quality of space. The location at the edge of the city means that it is not an active forum for urban life but a destination in its own right, a model of a miniature city where people define themselves not so much as consumers but as members of a wider community. Unlike in shopping centres, here we do not create our identity by making decisions within the limited product selection, instead, we can choose to stop consumption for a moment altogether and make use of the option to simply be and let our gaze wander on the dystopian runway, to stare at the mundane material environment in the showcases and look for a different meaning for the world—the museum space does not prescribe who you want to be exactly.

It is safe to say that the stories we have heard ever since the beginning of the century about the merchandising of museums and the transformation of all culture into an unending festival are greatly exaggerated. The new cultural buildings are good examples of state-commissioned public spaces that are quite self-aware with no desire to go along with the general trends of commercialisation. Considerably fewer new spaces for consuming culture have been constructed than rediscovered among already existing ones, the keywords for the past ten or fifteen years have been adjusting, intervention in the environment and project-based activities. The new cultural buildings seem to confirm that culture does not need only mobile project teams but also institutions, and, better still, the institutional buildings should consider the future and cover the surrounding hybrid processes. Kumu and ERM as prominent large-scale buildings but also several reconstructed museums such as the Seaplane Harbour are signs of their time, reflecting the transformed understanding of museums not as mere storage facilities but as places that speak to people and invite them to participate.

TRIIN OJARI is an architecture historian and the director of the Museum of Estonian Architecture.

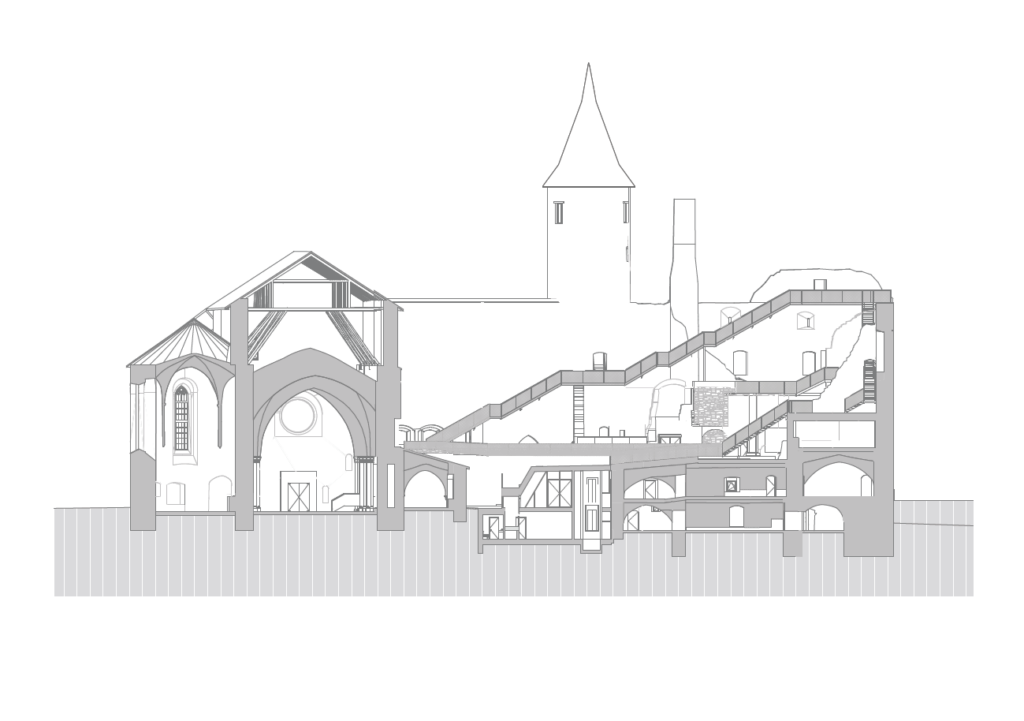

HEADER: Reconstruction of Haapsalu Episcopal Castle. Kaos Architects, 2019. Photo: Tõnu Tunnel

PUBLISHED: Maja 106 (autumn 2021) with main topic Spatial Revolutions

1 1 The most straightforward utterance of the idea originates from Rein Lang, the Minister of Culture in 2011-2013, but it was also expressed, for instance, by President Kersti Kaljulaid in her Independence Day speech in 2020.

See: https://kultuur.postimees.ee/420006/rein-lang-eesti-kultuur-vajab-manedzere,

https://www.president.ee/et/ametitegevus/koned/16450-eesti-vabariigi-aastapaeeval-paide-muusika-ja-teatrimajas/index.html

2 Peeter Rebane, „Uus keskus on väärt vana lammutamist“, Eesti Päevaleht, 10.11.2006.

3 Not a single new museum building had been built before the Second World War, with only two constructed during the Soviet period: Mahtra Peasantry Museum (Tiit Hansen, 1967–1970) and Võru County Museum (Kaarel Pedak, 1977–1983).

4 Ingrid Ruudi, „Visioonid uuest ühiskonnast,“ Ehitamata. Visioonid uuest ühiskonnast 1986–1994 (Tallinn, Eesti Arhitektuurimuuseum, 2015), lk 16.

5 The first stage of the art museum in Viinistu opened in 2002 may be regarded as the first reuse of industrial heritage in the function of art exposition.

6 Rem Koolhaas, „Bigness or the problem of Large,“ Small, Medium, Large, Extra-Large (New York, Monacelli Press, 1995).

7 Indrek Peil, Siiri Vallner, „Okupatsioonimuuseum,“ MAJA, 2003, nr 3, 24.

8 In 2007, a competition for common storage facilities of the visitor and restoration centre Kanut of the Estonian Open-Air Museum in Rocca al Mare was held with Kavakava’s solution selected as the best of the three entries.

9 Ingrid Ruudi, „Visioonid uuest ühiskonnast,“ (Tallinn: Eesti Arhitektuurimuuseum), 16.

10 Mariann Raisma, “Muuseum kui monument. Eesti uued muuseumimajad: unistused ja reaalsus 1990. aastate I poolel,” Eesti Rahva Muuseumi aastaraamat. 59. Tartu, 2016, 131–132.