Preservation has achieved cultural significance as a lens through which various urban experts have come to imagine what a socially and environmentally sound future might look like. As an approach, preservation has been applied to disparate phenomena ranging from historic neighbourhoods and natural environments to democracy and identity.

The Urban Studies programme in the Estonian Academy of Arts (EKA) has been unpacking some of the critical questions surrounding this discourse in a studio called ‘Preservation: Architecture, Nature and Politics’. Studio tutors Maroš Krivý—Professor of Urban Studies at EKA and Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellow at the Canadian Centre for Architecture—and Sean Tyler—a PhD student at EKA exploring the discourse of stewardship in contemporary landscape architecture—sat down with Kaija-Luisa Kurik for a discussion about the politics of preserving built and natural heritage.

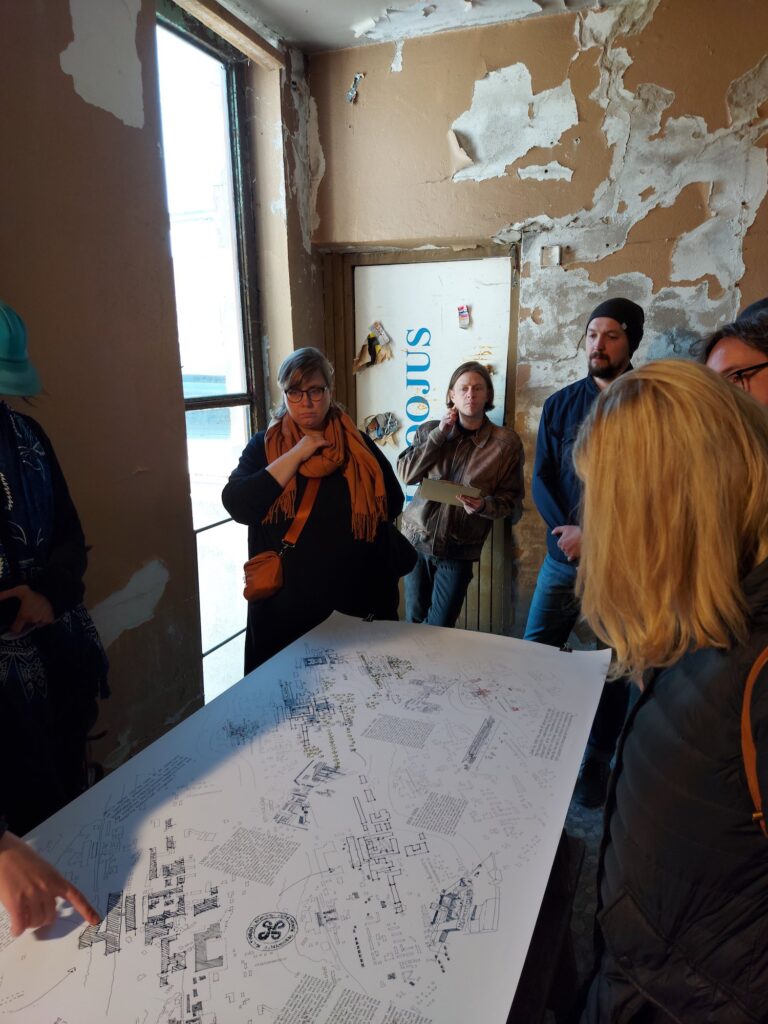

Kaija-Luisa Kurik: We have been running the studio ‘Preservation: Architecture, Nature, Politics’ in the EKA Urban Studies programme for three years now. When did the question of preservation become such a relevant framework for understanding contemporary urban issues and why? Are there any further educational potentials for architects and urbanists in this realm yet to be explored?

Maroš Krivý: With the studio, we emphasise that it is important to view preservation, conservation and related practices critically. For example, when something is preserved, who benefits and how? There are always decisions made about what should be preserved and how, and what shouldn’t be preserved. Decisions made by preservationists as well as the institution of preservation as such are shaped by ever-changing imaginaries that see certain objects as more valuable than others, but rarely provide space for reflecting on the criteria underpinning these judgments. From the perspective of critical heritage studies, heritage is a relational concept, and I would welcome the popularisation of this perspective in the Estonian arena. In other words, what we are preserving is not a physical object, but a relation of specific people to that object.

Sean Tyler: I think these ‘relations of specific people to an object’, as you put it, often play out where an institution that imagines particular historic and aesthetic significance and value to an object or ensemble of objects, but can be detached from the social relations and practices of those local people that inhabit them. I have been experiencing this actually first-hand where I live. It’s a 19th-century timber building that fronts onto the town square, where this one front facade is ‘protected’ and the municipality has argued that it has value as a kind of ‘postcard backdrop’ for the town. A small washing and sauna house was built, as there was originally no plumbing in the main building. The municipality argues that this smaller bathing house obstructs this postcard image and should be demolished. It also represents an image not necessarily attractive to some—something slightly ad hoc and Soviet. But this building has for many years been an integral gathering point of social relations, and without it, a number of residents would have nowhere to clean themselves.

How does someone decide what is kept and what is not, especially when you are talking about these social aspects? How do you measure these things? This is something that has intrigued me.

MK: Exactly—this is a very good example. One of the founding books of critical heritage studies, Uses of Heritage by Laurajane Smith (2006), touches on what Sean just said.

Smith introduces the concept of authorised heritage discourse—a professional discourse privileging expert values in the way we construct our relation to, and knowledge about, the past and how that past is manifested in the built environment. It is through that authorised heritage discourse that a sense of what heritage is, gets constructed. For Smith, authorised heritage discourse naturalises the ‘[i]mmutable and inherent nature of the value and meaning of heritage within the practice of heritage conservation and management’.1 I would emphasise that this discourse constructs equally a sense of what is not heritage (and thus the category of what we could call ‘non-heritage’ or even ‘anti-heritage’). In any case, the idea of authorised heritage discourse calls attention to what is outside of it, and thus to a range of other counterdiscourses or popular discourses not associated with or backed by professional experts authorising what is or is not heritage. Here, meanings are derived from peoples’ everyday lives and their experiences, such as—to return to Sean’s example—building a bathhouse because there were no bathrooms in the main building.

Kaija-Luisa Kurik: I wonder what would be some other really explicit examples of this—not necessarily from Estonia? Or is Eastern Europe or Estonia special for trying to impose certain aesthetically driven ideologies through preservation? Or is it like that everywhere?

ST: During the studio this year, we compiled a compendium where each student proposed an article on a topic that interested them. One of our students, Paula, contributed an excerpt from the book Shanzhai: Deconstruction in Chinese by Byung-Chul Han that explored Chinese and Japanese philosophy towards preservation. The excerpt explored the meaning and value of a copy. According to Han, the Chinese concept of a copy, fuzhipin (複製品), is very different from how we Europeans understand it—in fact, it has no negative connotations at all, and a copy in this sense is considered to have equal value to the original. Han describes the origins of preservation in Europe, where the preservation of historical monuments begins with the museumisation of the past, and cult value giving way to exhibition value. This goes hand in hand with the rise of tourism and the so-called Grand Tours that began in the Renaissance period, where ancient buildings and artworks acquired this kind of exhibition value and were presented as attractions.2 Han argues that this was when the first measures to preserve ancient structures were taken. Before that, we can find many examples of alterations of and removals from famous statues or structures. Han uses the example of the Colosseum, from which large sections were removed and repurposed for new buildings, alongside statues that, rather than being faithfully restored to the original form as is the tradition today, were in fact modified with additional elements and interventions to ‘improve’ them. This historical connection was interesting—the image of the building and that kind of museum value is highlighted as particularly Western phenomenon.

MK: Exactly. Since the late 19th century, the process of museumisation has gone hand in hand with the institutionalisation of preservation in national legislations. At the same time, the notion of heritage monuments belonging to the entire humanity is constructed through various international charters and agreements. Lucia Allais’ recent book Designs of Destruction: The Making of Monuments in the Twentieth Century examines the colonial legacy of this process.

One of her points is that the idea of heritage monuments became mainstream during the Second World War, when art historians and others compiled lists of objects that military bombers were instructed not to bomb. Yet again, one can ask how these notions of heritage operate against a kind of wider background of what is not heritage. It is interesting to trace historically how these assumptions change. Consider the case of industrial heritage. ICOMOS’s Athens Charter for the Restoration of Historic Monuments (1931), for instance, states that unsightly telegraph poles and all noisy factories need to be removed from neighbourhoods with artistic and historic monuments.3 So how does this square with the culture of preserving industrial buildings that has risen over the past half-century, first in the UK and more recently also in Eastern Europe? The irony is that the field of historic preservation is rather oblivious to its own history as a profession. Allais’s Designs of Destruction is one of the groundbreaking works that explores this history and how to build a bridge between histories of built environment and histories of expert practices centred around judging built environments as more and less valuable.

Kaija-Luisa Kurik: It seems almost self-evident and essential that in order to understand preservation practices, we need to look at historic processes, but also possibly consider future heritage. How are some of these ideas reflected in nature conservation, which is also relevant in the studio?

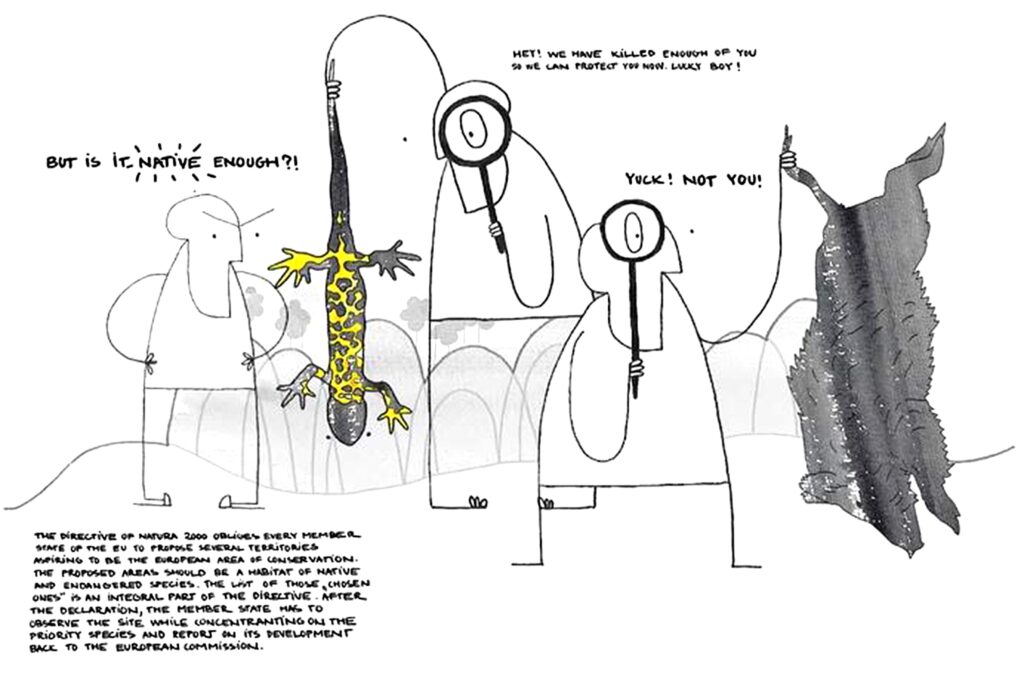

MK: Many experts and institutions see nature conservation as separate from architectural and urban preservation. Matthew Gandy discusses the case of London’s Abney Park, a socially and ecologically unique former cemetery threatened by development pressures.4 He shows that regulatory agencies involved in nature conservation such as Natural England don’t have the expertise or interest in protecting unconventional forms of nature, and recounts how the recent discovery of a rare species of fly in the park gave a boost to the grassroots campaign to protect the park.

Kaija-Luisa Kurik: Does this mean that the question of authenticity that runs through preservation of built environment also rises with regard to nature protection, leading us to these national debates such as, what is real Estonian nature like, what are the main local species and what is that valuable nature that is to be preserved?

MK: For a couple of decades now, the field of nature conservation has been questioning the paradigm of conserving natural areas for their beauty and moving towards the idea of conserving areas that are ecologically valuable. While assessing the value of natural areas on the basis of their function within larger ecosystems is clearly more scientific than using purely aesthetic criteria, ecosystems-based approaches to nature conservation are equally, if not more, implicated in the process of displacing indigenous people from the land deemed ecologically valuable. Bram Büscher and Robert Fletcher’s Conservation Revolution indicts the global nature conservation movement for its neocolonial and capitalist bias, and puts forth what they call convivial conservation as an alternative. Their idea of convivial conservation moves beyond both purely aesthetic and purely scientific approaches to nature conservation to address the role of economic and political frameworks within which conservation operates, and the question of socio-environmental justice. The goal of convivial conservation, Büscher and Fletcher write, is ‘not setting nature apart but integrating the uses of (nonhuman) natures into social, cultural, and ecological contexts and systems’.5

Kaija-Luisa Kurik: Some of these topics we touched on in the first year of the studio, when we focused on wastelands and wetlands as landscape typologies. Student projects compared how the term ‘wasteland’ is understood in different cultures and languages; explored the interplay between wetland restoration programmes and the oil shale industry in neoliberal Estonia; traced the socialist origins of revegetating spoil banks in Czechoslovakia; examined how John Locke’s labour theory of value, settler colonialism, and commodification of nature have intersected in Charleston, South Carolina; and addressed other political, institutional and technological complexities of revaluing nature.

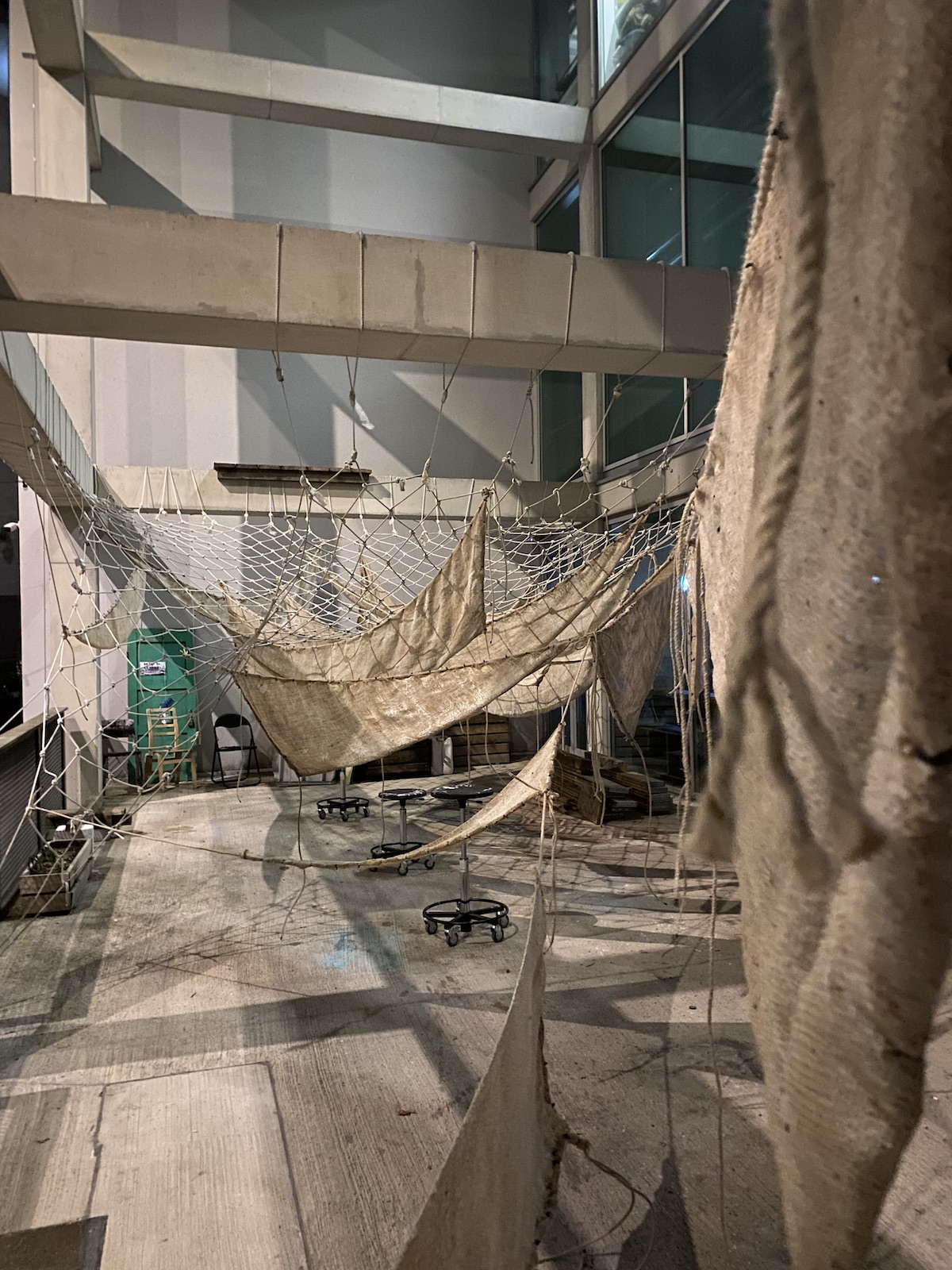

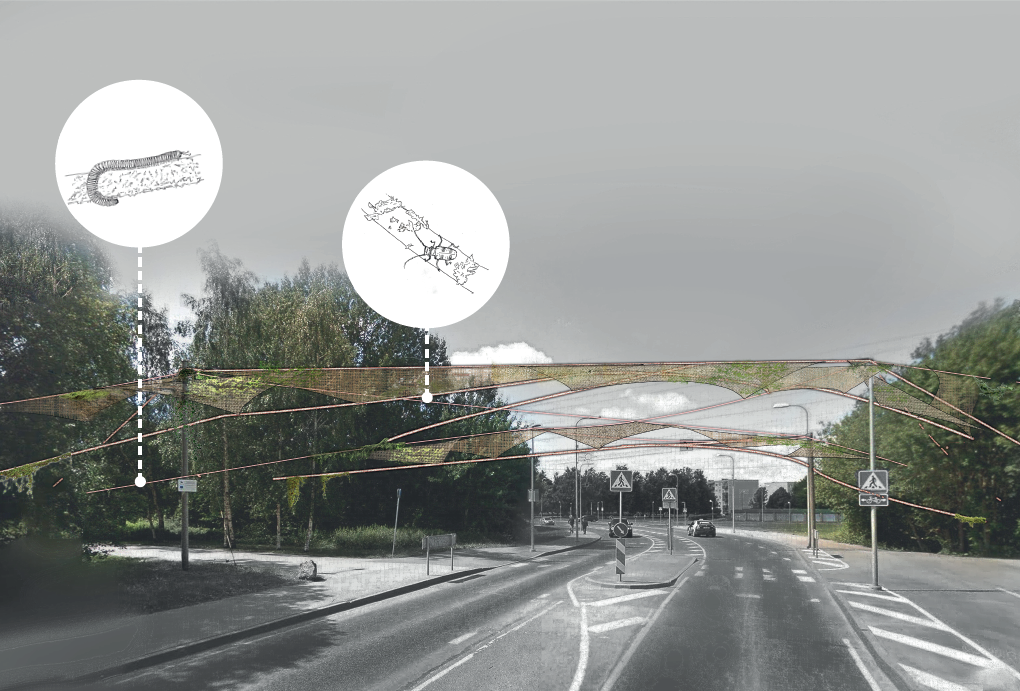

In the course of the studio in 2022, students were asked to participate in an installation project titled ‘Place Buzz’ for Putukaväil (Pollinator Highway), and approach it through the lens of preservation. One of the student installations that envisaged a path for insects across a busy road was recently built. Where do you think the case of Putukaväil more broadly sits in these debates?

ST: It’s a loaded project. While it is promoting real estate development around the site, it is also providing a large attractive public space for citizens. It is difficult to navigate between the project’s intentions and outcomes. It is a tricky thing to talk about, let alone do a proposal for. The students managed to produce some interesting projects in a couple of weeks. The ‘Interspecies Crossing’ project played with the appeal of Putukaväil as a seamless mobility highway, and despite the conceptual attraction, there are a number of busy intersections that create disconnects along it.

Kaija-Luisa Kurik: I guess it is an ideal example of an attempt to bring theory and practice together that demonstrates how difficult and quite often problematic it is.

MK: Putukaväil is an interesting case that I would like to do more research on. It is emblematic of a ‘green’ shift in how municipalities think and act. Specifically, the idea of a less intensive mowing regime—which echoes initiatives such as NoMowMa, the idea of not cutting grass in the month of May—reflects the growing appreciation for the presence of spontaneous nature in cities. Yet, it also opens up tensions among and between residents and urban professionals. For many residents, unmowed equals unkempt, neglected or even dangerous. Urban professionals must avoid looking down on these residents from a position of supposedly superior knowledge—rather, they need to consider the role of class, age, ethnicity and gender in shaping aesthetic preferences and everyday urban environments.

The potentially negative social impact of environmental projects such as Putukaväil is an important concern. Whose imaginaries about what a good city is like shape the project? Who stands to benefit, and who loses from it? Scholars have introduced the concept of green gentrification—‘The creation or restoration of an in situ environmental good [that] will increase environmental inequality, as the amenity drives up property values, physically displaces those at the lower end of the stratification pyramid, and attracts new residents at the higher end.’6 In Tallinn, a discussion of these issues has been launched by Bianka Plüschke-Altof and Karina Vabson, but more work is needed to foreground social and environmental justice questions in the urban arena.

Kaija-Luisa Kurik: How do you, Sean, relate to this working in the field? I imagine a lot of projects involve these dilemmas on the urban scale.

ST: Yes. Being aware of the potentially uneven transformation of neighbourhoods that comes with a large-scale project and attempting to negate some of these effects is the bare minimum I think that professionals should undertake. There are many positive qualities that can be realised with a project that brings together such a large public space. There is the potential to regain control over food production and provide subsistence if the city were to designate areas of Putukaväil open to urban gardening. More than providing food security, these areas can act as centres of knowledge and cultural production and exchange. Perhaps most importantly, they generate value not for commercial purposes, but for the residents. This has been done effectively throughout Tallinn, but at a much smaller scale, and there is at least one community garden (Pelguaed) already established on Putukaväil.

Maroš was talking about that 1970s moment of ecological value being prioritised over aesthetics. I think these meadows can be seen as a modern-day archetype. They produce biodiversity, reduce labour costs associated with mowing, and the gardens no longer require uprooting of annual plants as these are replaced with perennials. However, this shift also requires specialised knowledge and centralised management of working within these landscapes, which can accentuate existing inequalities within the maintenance workforce.7 Balancing these predominantly performative landscapes with areas for social exchange such as urban gardening or projects like the seedball proposal could be an effective method for producing more just socio-environmental relations.

Kaija-Luisa Kurik: I guess this links preservation and heritage practices more generally to the question of gentrification. We discuss gentrification in classes with young urbanists and theorise over it in our academic texts as well, but it presents a huge dilemma. Some kind of change management is needed, but at the same time, how do you also manage the harm you cause? Who benefits and who doesn’t, and how do you bring about that awareness? These questions are also discussed in the studio.

ST: This also reminds me of one of the student group proposals for the ‘Place Buzz’ competition at Putukaväil. They proposed to initiate cooperation between local kindergartens, schools and an educator/ecologist to conduct workshops on creating seedballs that would be distributed in seedball machines. The objective was to create a participatory intervention that encourages people to learn about the important ecological benefits of urban meadows while at the same time engaging with local stakeholders through the building, self-planting and maintenance process.

MK: We are witnessing an interesting moment. Another example is Männi park in Mustamäe, originally a byproduct of an abortive project for a neighbourhood centre, which recently went through a substantial transformation. It is widely frequented and integrates diverse groups of users. It’s not an ‘avant-garde’ design, nor a destination you’d visit if you live downtown. But perhaps this is what makes it special. The case highlights the potential of mikrorayon landscapes to function as a form of public space, and the fact that residents indeed use and care for them. As architectural historian Christina Crawford argued, there is heightened significance in maintaining what she calls ‘socialist space’ as ‘an alternative bodily experience to the enclosed and exclusionary spaces of neoliberal capitalism’.8

KAIJA-LUISA KURIK is the project manager of the partnership project between the Estonian National Heritage Board and Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage titled ‘Historic Town Centres Revitalised Through Heritage-led Local Development’. In addition, she is an acting coordinator of the Urban Studies programme in the Estonian Academy of Arts, and also teaches urban studies and architecture students in the Manchester School of Architecture.

HEADER: A historic timber building and later addition of a bathhouse/sauna. Photo: Sean Tyler

PUBLISHED: Maja 109-110 (summer-autumn 2022) with main topic Built Heritage and Modern Times

1 Laurajane Smith, Uses of Heritage (London, New York: Routledge, 2006), 6.

2 Byung-Chul Han, Shanzhai: Deconstruction in Chinese, tlk Philippa Hurd (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2017), 66.

3 ICOMOS, „The Athens Charter for the Restoration of Historic Monuments (1931)“, http://www.icomos.org/en/167-the-athens-charter-for-the-restoration-of-historic-monuments.

4 Matthew Gandy, „The fly that tried to save the world: Saproxylic geographies and other‐than‐human ecologies“, Transaction of the Institute of British Geographers 44 (2) (2019): 392–406, https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12281.

5 Bram Büscher, Robert Fletcher, The Conservation Revolution: Radical Ideas for Saving Nature Beyond the Anthropocene (London: Verso, 2020), 295.

6 Kenneth A. Gould, Tammy L. Lewis, „The environmental injustice of green gentrification: The case of Brooklyn’s Prospect Park“ raamatus The World in Brooklyn: Gentrification, Immigration, and Ethnic Politics in a Global City, toim Judith DeSena, Timothy Shortell (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2012), 113–146: 114.

7 Marion Ernwein, ‘Bringing Urban Parks to Life: The More-Than-Human Politics of Urban Ecological Work,’ Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 2020), 12

8 Christina E. Crawford, „The Case to Save Socialist Space“, Research Companion to Landscape Architecture, toim Ellen Braae, Henriette Steiner (London: Routledge, 2019), 260–274: 261.