Rotermann Quarter stands out for the diversity of its new-builds and reconstructed former industrial buildings. There is probably no other area in Estonia awarded with as many prizes as this one. Mathilda Viigimäe and Kristi Tšernilovksi shed light on the architectural development of Rotermann Quarter.

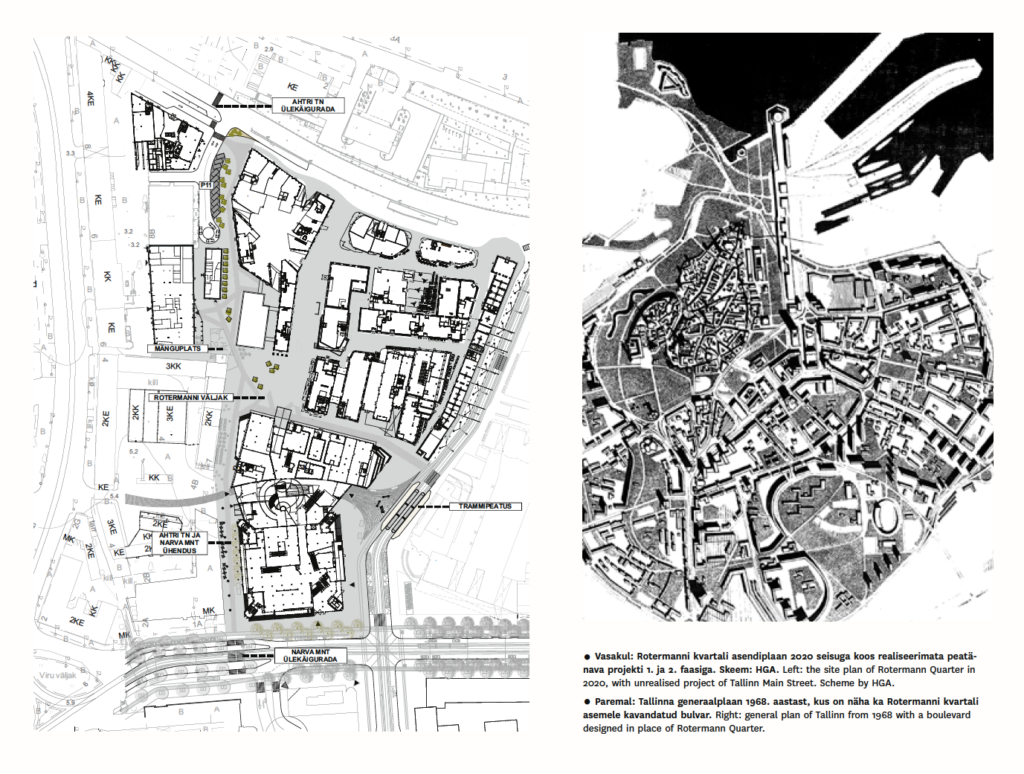

In the heart of Tallinn between the port and Viru Square, there is a well-preserved industrial district dating back to the early 19th century. The trading courtyard of the building material export and import company established by Christian Abraham Rotermann became one of the largest industrial areas in Tallinn in the early 20th century including factories and facilities of various business sectors. Over the years, food factories were constructed in the area and also one of the first car dealerships in Estonia. The heyday of the quarter was perhaps the beginning of the 20th century when the area kept expanding in the wake of the urbanisation process.1 It all came to an end with the Soviet occupation when the successful large private company was nationalised and production restricted. In 1970s, there were plans to eliminate the district altogether to make room for an extra-large pedestrian avenue from the harbour directly to Viru Hotel. In the same decade, also the scenes preceding the zone entrance in Andrei Tarkovski’s film ‘Stalker’ were filmed in the already decaying complex. As the Soviet period had a devastating effect on the industrial district and buildings were in a truly miserable condition, the reconstruction of the quarter was considered unlikely. In 2001, the multiplex cinema Coca-Cola Plaza was opened between the post office building and the quarter and in the same year the entire area was declared a built-up area of cultural and environmental value.2 This marked the beginning of the rejuvenation and reconstruction of the quarter into a more welcoming area.

The basis for the perception of space

In the early 21st century, it was decided to give the abandoned quarter a new lease on life with a proper purpose. In her article in 2002, Epp Lankots expressed her concern that in the light of the new bold ideas and plans, Rotermann District would probably lose its mysterious and Stalker-like feel. The modernisation of industrial areas might have been a common practice in Western Europe but it was an entirely new concept for Estonia. The whole project tarried also because of the local investors who did not consider the renovation plans sufficiently convincing.3

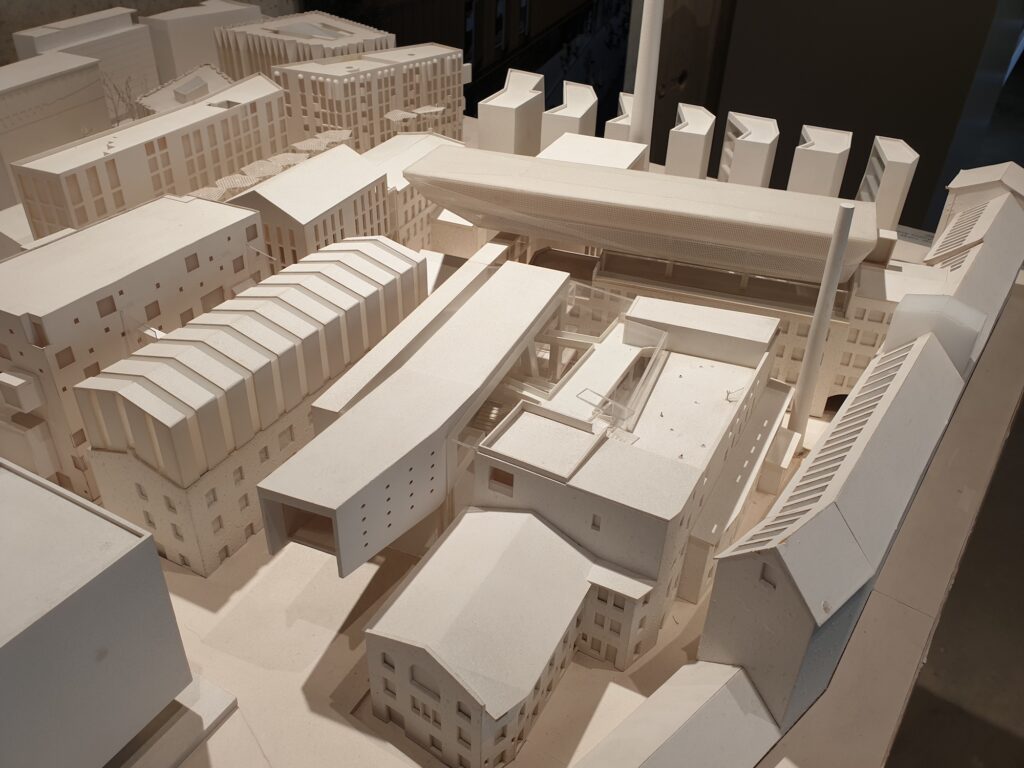

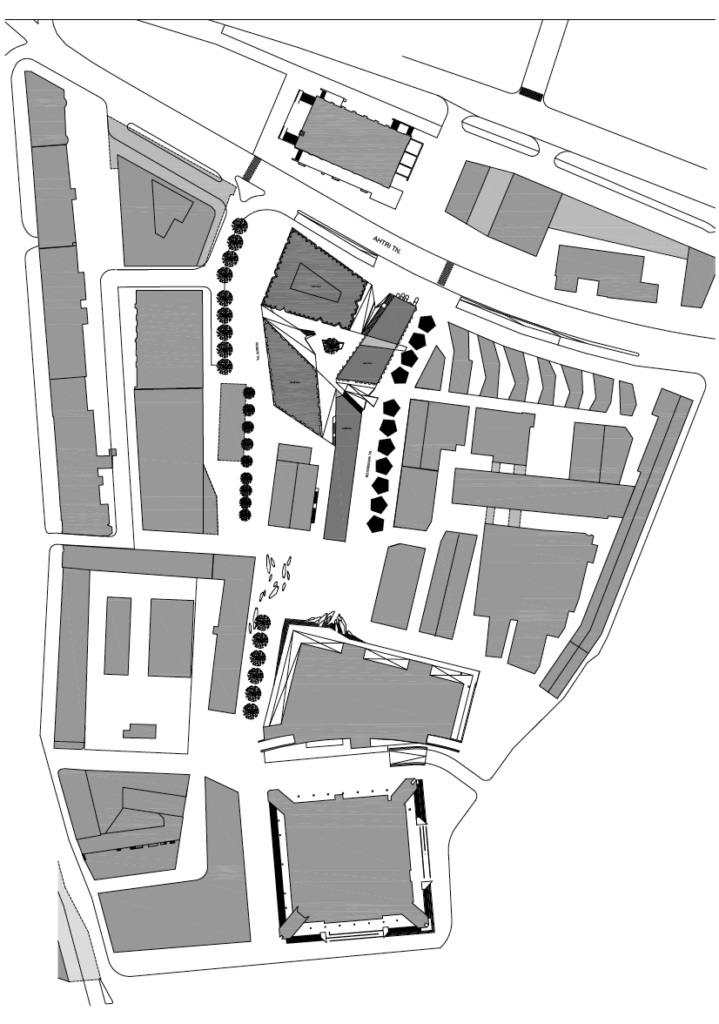

In 2002, the zoning plan of Rotermann Quarter compiled by Andres Alver and Veljo Kaasik and commissioned and assisted by the management board of the Estonian Association of Architects was approved. The first two floors of the buildings were to have public functions and open to the street. The zoning plan also provided that vehicles are allowed to the area between the buildings only in case of emergency: it was primarily meant for pedestrians and vehicles were to be parked either underground or on the top floors of the buildings. The new Rotermann Quarter could thus become denser than the Old Town. According to Alver, it was facilitated by highly flexible regulations that ruled out only single particular aspects. It was important to retain the unique structure of the quarter—its fragmentation, density and diversity.4 The rules of the zoning plan were put together in cooperation with the developer Manutent OÜ and heritage conservation specialists who determined the protected buildings as well as the height of the new-builds—24 metres pursuant to the ventilation chamber dimensions of Coca-Cola Plaza.5 The given zoning plan and building regulations formed the basis for the construction of the entire quarter and provided a good overall picture of the area in the future while reconstructing the original buildings.

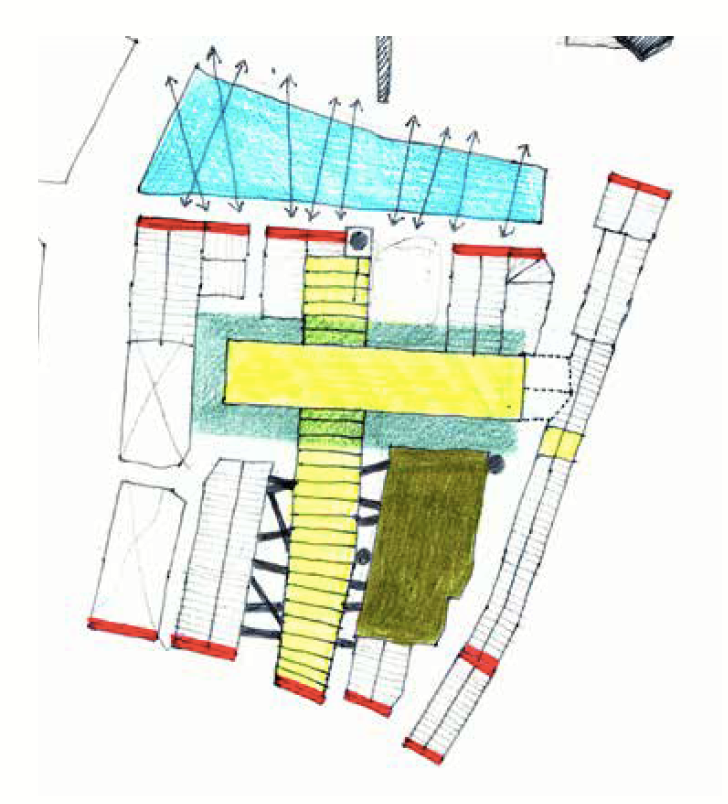

In 2005, commissioned by the developers, Alver Arhitektid drew up the general spatial development plan that for a long time formed the conceptual basis for the spatial development but came to be abandoned in case of the more recent buildings.5

The continuing searches and new breathing

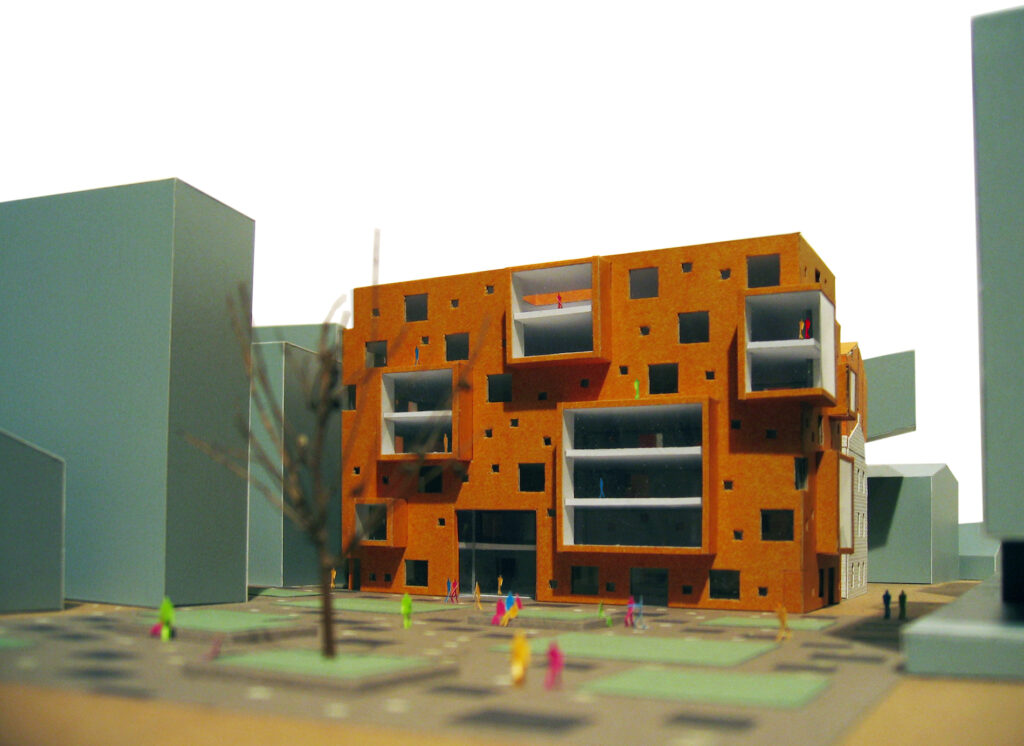

The first new-builds at Rotermanni 5 / Roseni 10 were completed in 2007 (architects Ott Kadarik, Villem Tomiste and Mihkel Tüür). Although the detail plan provided one large building volume on the site, the architects decided that the area would benefit from a more sensitive approach. As a result, four smaller buildings: Orange, Black, White and Brown Building were constructed. According to Tomiste, the entire project came to be affected by its proximity to the Old Town and the general use of street space similar to Mediterranean towns.6 The emphasis in the design was to provide flats of various typology that would allow the residents to match them to their needs and wishes.7 The ground between the apartment buildings was raised by one floor to increase the number of commercial premises open to the street front. For their experimental approach to the four town houses, Kadarik, Tomiste and Tüür were awarded the State Cultural Award in 2008.8

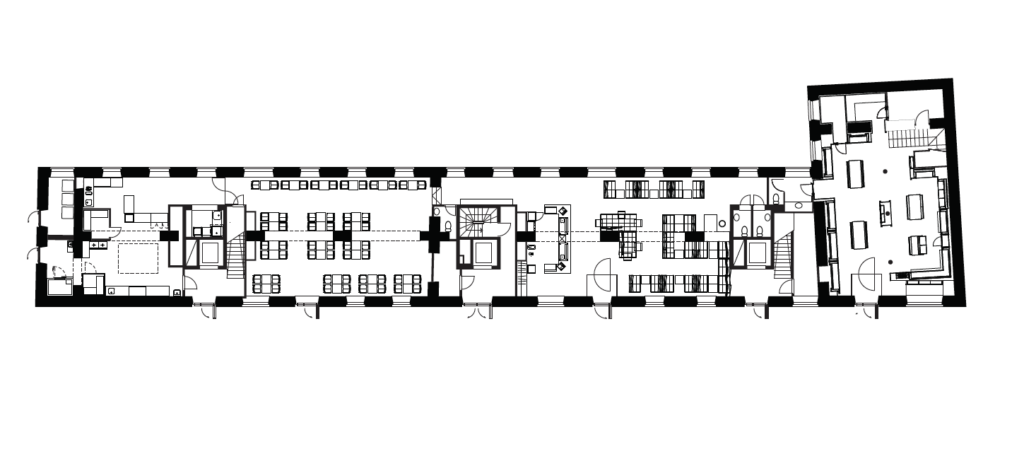

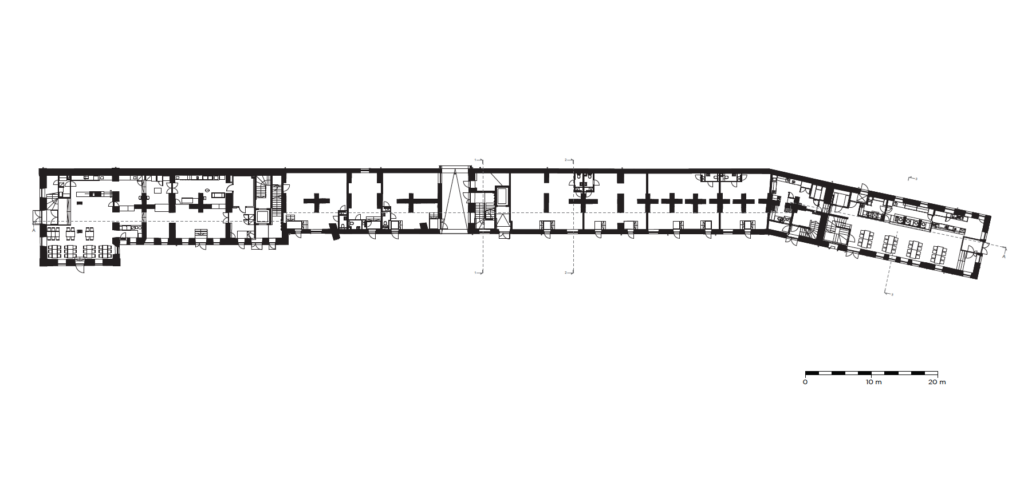

In 2007, the former barley mill (Teigar Sova Arhitektid) and a year later also the sampling mill (Emil Urbel ja Ainar Luik) were reconstructed, both in keeping with the original architectural solutions and without adding anything innovative to the buildings. The former mills now accommodate commercial premises and offices.

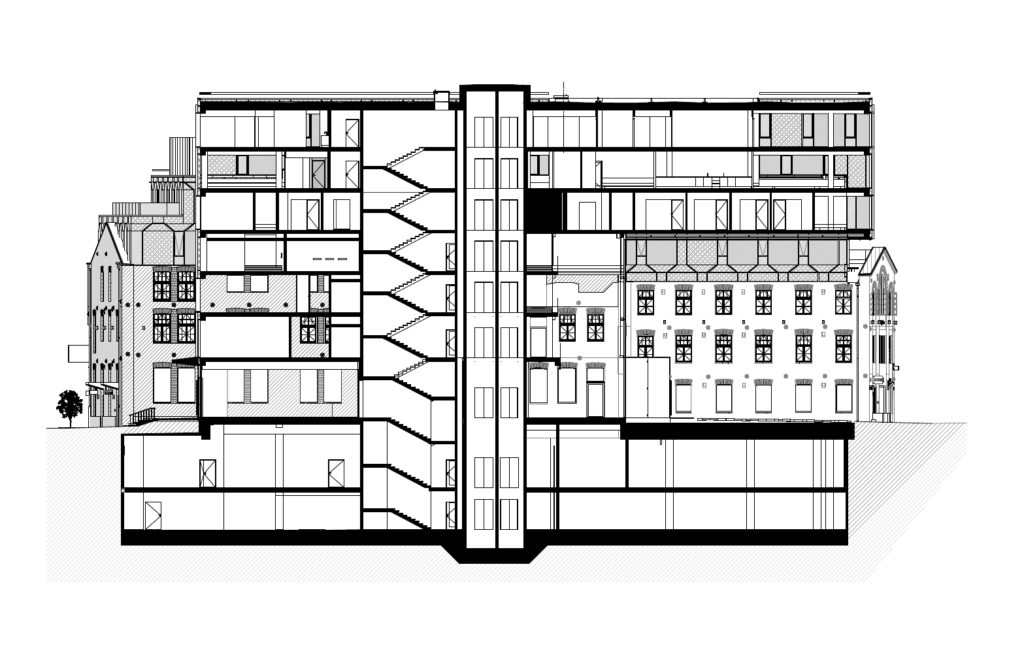

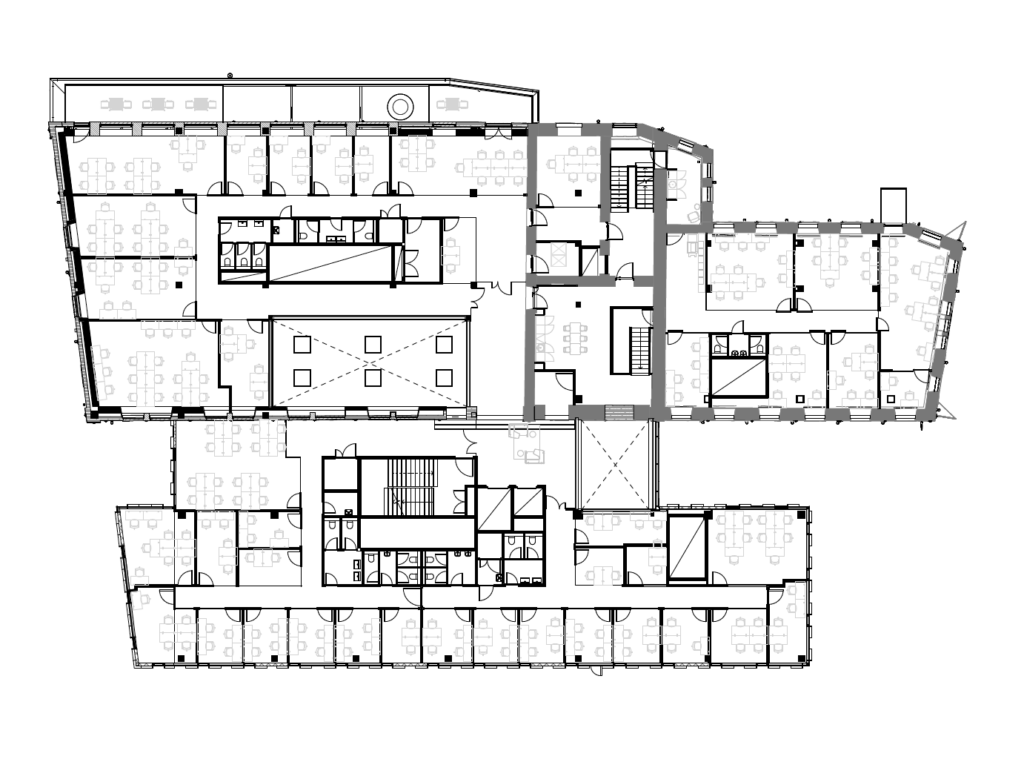

The next major stage was the reconstruction of the southwestern part of the quarter.9 In 2009, the construction of commercial and office buildings in the New and Old Flour Storage (HGA) was completed with the proportions of the various openings in the abstracted façade solution relating to the old industrial buildings of the historical district.10 The façade of the Old Flour Storage built in 1904 is under heritage protection much like the facades of all other industrial buildings in the quarter. According to the special conditions of heritage conservation, all limestone facades had to be maintained and restored to their original appearance.11 The historical flour storage building is connected to the adjacent newly constructed office building with a glass section, while on upper floors there are ramps leading to the historical openings in order to retain the original substance of the historical construction as much as possible. The main façade was clad in weathering steel suggesting the building’s original function as a factory and also relating to the rustic materials of the surroundings. Limestone walls, brick lintels and oxidised steel details were meant to pay homage to the area’s industrial past.11 The new and old architecture have been carefully combined into a comprehensive whole featuring a fine perception of the shared density. The architects’ vision was awarded the Annual Award of the Cultural Endowment of Estonia in Architecture in 2009.

The same year also witnessed the completion of the Carpenter’s Workshop by KOKO across the square, which according to Raivo Kotov relies on its bold architecture to entice people from Narva Road and between the former post office building and Nordic Hotel Forum into the quarter. The Carpenter’s Workshop is the tallest office building along the square as the architects placed glass towers containing office facilities on top of the historical building with new reinforced concrete posts. The three polygonal techno-futuristic volumes are inspired by the endless repetitive elements of industrial landscapes and also by the Nitrofert cooling towers seen during the visits to factories in Ida-Viru county.12,13 The office towers were originally supposed to be covered entirely by glass, however, the economic recession put brakes on the idea. At one point, the developer had even considered leaving the towers out altogether but fortunately there was no need for such drastic measures. According to Kotov, time has shown that the triangular windows were actually a better solution than the full glass façade, especially when considering the indoor climate. The tapering towers designed with red light have not left people indifferent either—some call them Christmas trees, but also architecture historian Mart Kalm has highlighted their airiness characteristic of industrial architecture.14

According to architecture critic Carl-Dag Lige, ‘the reconstruction of the Carpenter’s Workshop as a protected limestone building reflects the highpoint of the economic boom era when private clients had the desire and courage to carry out also the more extravagant solutions. On the other hand, the reconstructed workshop reflects the attempt of heritage conservation institutions to reconceptualise the relations between historical and contemporary architecture’.15 Bold choices and the reconstructed buildings were acknowledged also in the international architectural arena: in 2009, it was shortlisted for the Mies van der Rohe Award, an achievement so far unsurpassed by Estonian architects.

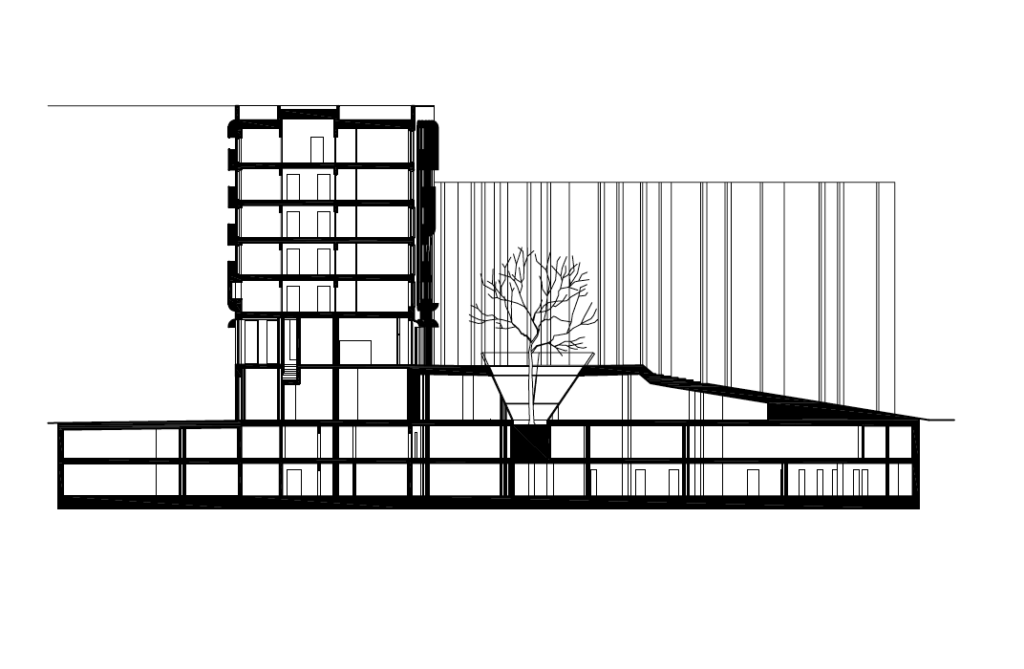

In the same year, KOKO completed also the Metro Plaza building along Viru Ring Road that used to be the department store of Rotermann Quarter. At present, it is an office building featuring contrastive architecture right along the city’s artery. The building was initially supposed to become a V-shaped hotel but the developers were not too keen on the idea and eventually agreed on a large-scale office building. The building at Rotermanni 10 (Alver Arhitektid) completed in 2013 is a good example of the densification of an existing environment based on the earlier constructional concepts. The building aims at forming an integral part of the organic whole of the quarter and create new spatial situations among the old buildings.16

In 2016 and 2017, a number of new and reconstructed buildings were completed in the quarter, including the Elevator Building along Hobujaama Street (KOKO). The former grain elevator was probably the most complex building to renovate in Rotermann Quarter as in order to retain its authentic appearance, it was not allowed to add any doors and windows on to the outer perimeter. Due to the meagre light conditions, it took a long time to find a suitable function for it. The initial idea to turn it into a spa was abandoned for a combination of commercial premises, dance studios and offices. The elevator building had been long without a roof and by the time the design process began in 2006, the condition had become critical. Due to the economic recession a couple of years later, the project was put on hold and revived only in 2013. According to KOKO architects, the main (interior) architectural starting point was to ‘maintain and expose the building’s historical appearance, to make a clear difference between the old and new structures, add new details of minimalist style and primarily take the building itself as the basis in everything’.17 In the interior, they focused on the maintenance of the concrete bunkers together with the limestone posts between them, they also wished to retain all the metal straps with the numbers painted above the hoppers. A considerable part of the technical equipment was retained in the tower at the northern end of the elevator. It was decided to keep the authentic stone surfaces and concrete constructions exposed. The Grain Elevator building was awarded the best restored building prize by the Estonian National Heritage Board in 2016.

The glassy look of Rotermann

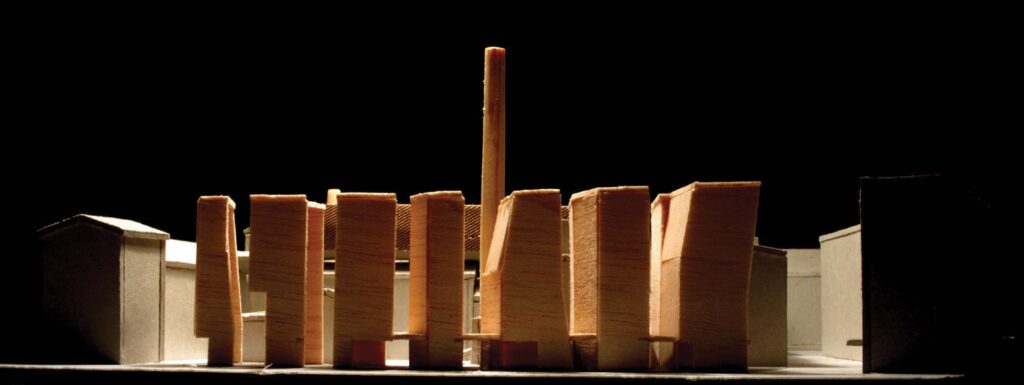

The buildings constructed since 2017 are marked by noticeable deviations from the initial zoning and development plans and instead feature a more commercial feel. The large complex at Rotermanni 14 (Arhitektuuriüksus, 2017) including the former power station, the rye, wheat and flour mills and the chimney was completed in 2017. The formal features of the new restored complex differ considerably from the historical buildings and include offices, apartments as well as various commercial and service facilities open to the street front.18

Also the two large buildings, Gold and Red Building, were completed at Rotermanni 18 (HGA) in the same year, marking the seaside border between the quarter and Ahtri Street. The modern and airy glass twin building provides its users with a new and more private area within the quarter but at the same time also separates the environment from the rest of the city. Both Gold and Red Building primarily accommodate apartments and offices. The most recent building in the area is Ajamaja (KOKO) with its office premises largely defining also the eventual layout plans. It relies on the dramatic effect of its glass façade to attract people’s attention already from a distance in Laikmaa Street.

The buildings constructed after the Grain Elevator no longer search for innovative and perceived relations to their historical environment. The stakeholders’ courage to experiment with architecture and urban design that used to characterise the development of Rotermann Quarter prior to the economic recession in 2008 seems to have faded in the changed economic climate.

A layover 2022

According to architects Raivo Kotov and Ingrid Viskus (KOKO), the development of the quarter as an organic whole has been consistent—starting from the zoning plan by Alver Arhitektid and the bold attitude taken by AB Kosmos up to the developer’s decision to make every building a separate work of art and thus avoid the modular copy-paste buildings that you usually come across in innovative industrial areas. Kotov also says that none of the buildings in the quarter has been motivated by the will to upstage the previous ones, instead, each building has its own characteristic function, prominence and historical background. On the other hand, one of the authors of the zoning and development plan Andres Alver states that the full potential of the urban design plans allowing a lot of freedom and possibilities is far from being fulfilled.19 The unique feature of the quarter lies in the juxtaposed worlds bringing together dense housing and the fragmentation of the particular features of the buildings with all the accessible areas and nooks. Perhaps the attraction of the quarter is indeed ensured by its initial experimental and subsequent commercial spirit.

However, the constructional assembly and all the other forceful features have left the particularities of public spaces in the background, including planting and outdoor terraces that today form an essential part of a well-functioning urban space. At present, the functioning of the new centre as well as the public spaces in Rotermann is mostly affected by accessibility. If in Tomiste’s opinion, the streets within the quarter are occasionally too narrow leading the logistics to the outer perimeter of the quarter and thus partly separating the area from the surrounding city, then Kotov has always been annoyed by Coca-Cola Plaza, as the closed large volume does not fit the historical feel of the quarter and even obstructs accessing it.

We may, thus, ask if Rotermann Quarter is a set of awesome buildings rather than an ideal public space. It is up to us to decide on the appropriateness of the metaphor of a city within a city is or on the current efficiency of the quarter, however, it remains a fact that the urban design plans dating back to the early noughties had the potential for the development of a highly versatile and unique space. Rotermann Quarter is definitely one of the most complex and intriguing spaces developed in Estonia during its independent years.

MATHILDA VIIGIMÄE is a third-year student of architecture and urban design at the Estonian Academy of Arts.

KRISTI TŠERNILOVSKI is a third-year student of art history and visual culture at the Estonian Academy of Arts.

HEADER: Model of Rotermann Quarter. Alver Architects, 2005.

PUBLISHED: Maja 108 (spring 2022) with main topic Opening Tallinn to the Sea

1 „Meie lugu“, Rotermann City, kasutatud 15.12.2021, http://www.rotermann.eu/ajalugu/.

2 Karen Jagodin, Robert Nerman, Jalutaja teejuht – Tallinna kesklinn, (Tallinn: Solnessi arhitektuurikirjastus, 2013).

3 Epp Lankots, „Mida teha varemetega?“, Sirp, 19.04.2002.

4 „Rotermanni kvartal“, Alvar Arhitektid, http://www.ata.ee/lens_portfolio/748/?lang=et.

5 Andres Alver, e-mail correspondence with the author, 21.03.2022.

6 Villem Tomiste, e-mail correspondence with the author, 11.03.2022.

7 „Rotermann house“, Archello, retrieved 18.03.2022, https://archello.com/project/rotermann.

8 „Kultuuripreemiate laureaadid“, Ministry of Culture , https://www.kul.ee/kultuuripreemiate-laureaadid#item-15.

9 Kalle Komissarov, „Rotermanni saaga“, KMG ehitus, retrieved 27.06.2005, http://ehitus.kmg.ee/kmgehitus.ee/meist/index7d89.html?content=86&itemId=16&subId=110.

10 „Rotermanni Vana ja Uus jahuladu“, HGA, http://hga.ee/rotermann-old-and-new-flour-storage/.

11 Tallinna kultuuriväärtuste amet. Rotermanni 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 14, Ahtri 4C, 4D. Detailplaneering. Muinsuskaitse eritingimused. Koost. L. Välja. 24.02.2006, lk 6.

12 Andrus Kõresaar, Raivo Kotov, KOKO arhitektid: 15 aastat (Tallinn: Tallinna raamatutrükikoda, 2014), 179.

13 Karin Paulus, „Eesti hetke menukaimad arhitektid“, Eesti Ekspress, 18.05.2012.

14 Mart Kalm, Eesti arhitektuuri 100 aastat. (Tallinn: Post Factum, 2018), 145.

15 Carl-Dag Lige, „Laudsepatöökoda. Intrigeeriv büroohoone ajaloolises tööstuskvartalis“, http://www.kokoarchitects.eu/et/project/96-roseni7-carpenter-s-workshop-reconstruction.

16 „Rotermanni 10 kortermaja“, Alver Arhitektid, http://www.ata.ee/lens_portfolio/rotermanni-10-kortermaja/?lang=et.

17 Eesti Arhitektuuripeemiad 2017. Interview with KOKO architects.

18 „Rotermanni korsten; jõujaam; rukki-, nisu- ja jahuveski“, Arhitektuuriüksus, https://arhitektuuriyksus.ee/rotermanni-14.

19 Andres Alver, e-mail correspondence with the author, 21.03.202