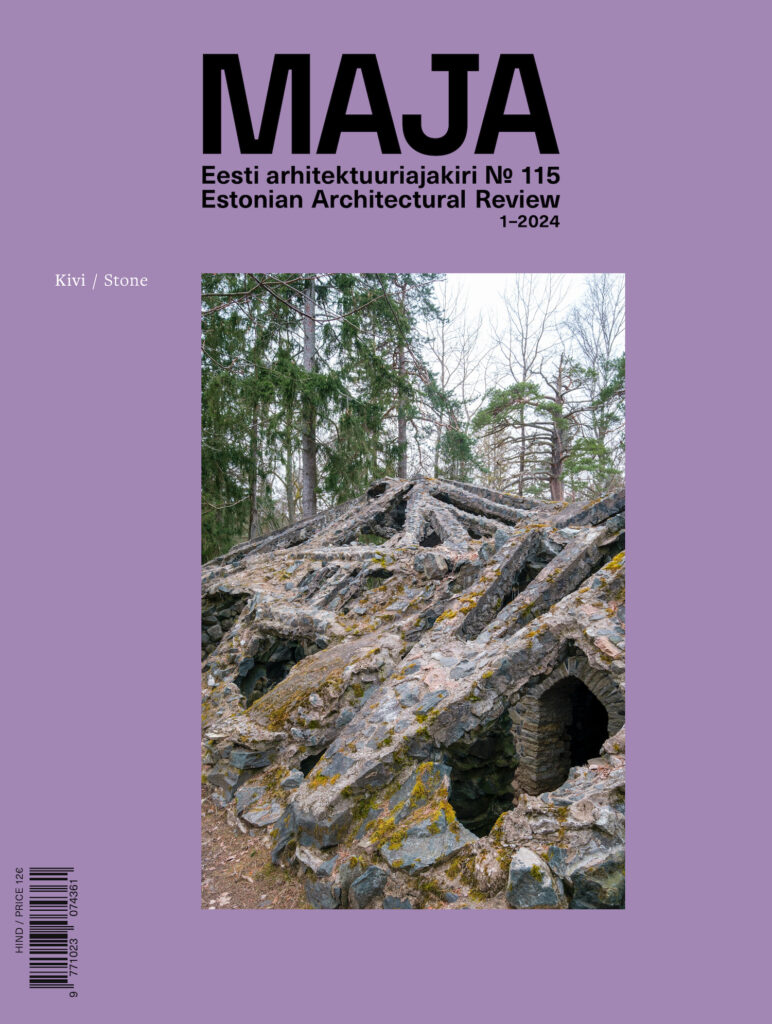

The Rotermann Quarter was the first ambitious attempt in independent Estonia to create a comprehensive and architecturally high-level urban space. 20 years have passed since the confirmation of the zoning plan that underlies the development of the area. Urbanist Mattias Malk examines what lessons could be drawn from the formation of this emblematic and groundbreaking space.

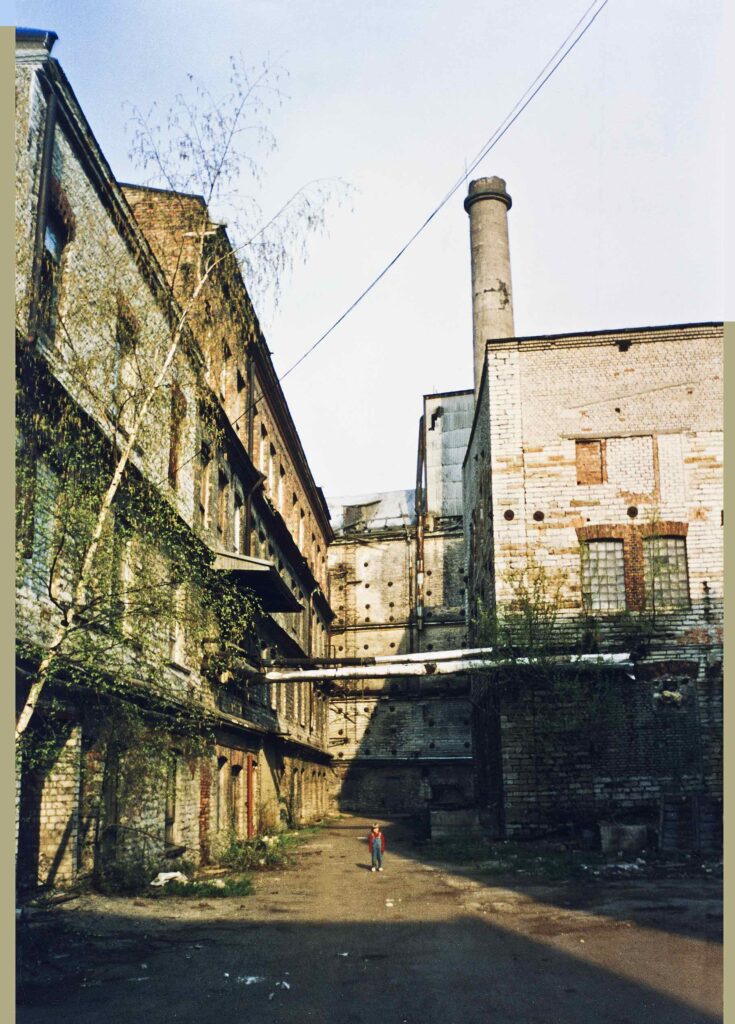

The first buildings of the reconstructed Rotermann Quarter were opened in 2007. The future seemed bright. Estonia had just joined the European Union and NATO. The peak of economic growth had not yet been reached. Ecstatic consumerism in the post-independence society was turning the economy from the East to the West, from the industrial sector to the service sector. Construction seemed to be happening everywhere—especially in the fields around cities, where single-family shell homes, funded by liberally provided home loans, kept popping up amid deficient infrastructure. Urban life began to seep away from public spaces and concentrate in shopping centres, and cars became an inextricable part of the everyday mobility of the middle class. At the same time, a car-free quarter was being developed in Rotermann, which strived for urban density and considerate construction. It has become one of the most emblematic and successful urban space developments in Estonia, but nevertheless remains foreign to the average city dweller for a host of reasons.

Strategic and accidental successes

In part, the success and distinctiveness of Rotermann were driven by architects Andres Alver and Veljo Kaasik, who worked with various municipal authorities in Tallinn to put together a zoning plan, which was confirmed in 2002. This document was, in a way, a groundbreaking precedent in the urban development of Tallinn—the first to clearly acknowledge the duty of the city in steering its spatial development, and the first to delimit private interests which had come to reign supreme. The city declared for the first time: ’whether you own the plot or not—urban space belongs to everyone’.1 In addition to acknowledging the dangers of exploitation by developers, the architects had a good understanding of the social and historical value of the Rotermann Quarter, as well as its potential to connect the city and the seaside, which had been drifting apart in their development for decades. The plan laid down clear rules in terms of height restrictions, building rights and protected views.

It also set the general priorities for the development of the area:

– creating a diverse, attractive and public urban space for pedestrians, which would be serviced and framed by the surrounding private capital buildings;

– ensuring the preservation of and visual access to any heritage objects;

– achieving a consistent look and suitable spatial solution for the area.2

The plan was nevertheless developer-friendly and accommodating on the part of the heritage board, allowing all plots to be 100% built-up. Still, the 24-metre height restriction thwarted the intention of OÜ Aswega, which administered the plots by Mere pst., and architect Ülo Peil to build a high-rise by the Viru Square where Metro Plaza stands today. The dispute became quite heated—Aswega accused the city authorities of wilfully misleading the plot owners and claimed that the whole zoning plan is void.3 However, the planners together with architects Alver and Kaasik held the line and parried the developer’s protests, and thus, the zoning plan became a significant proof of the city’s growing backbone.

From there on, the development of Rotermann has been largely in the hands of Urmas Sõõrumaa, who owns most of the plots bordered by Hobujaama and Ahtri street. At first, Sõõrumaa operated together with Märt Vooglaid under the company name Manutent, but in September 2005, the enterprise’s assets were divided, and Sõõrumaa’s U.S. Invest was left with Rotermann. Unlike Aswega, Sõõrumaa clearly understood the long-term potential of Rotermann, embraced the zoning plan without protest, and gradually began implementing it. One of the leading principles in the plan was that every building constructed in Rotermann should be the result of an architectural competition, and created by different architects if possible. Endrik Mänd, who was the city architect at the time, is convinced that this is why all the buildings in Rotermann have architectural significance, rather than being just some buildings of their time, in a city of their time.4 Mänd recounts that other developers found the architectural and spatial solutions in Rotermann to be overly vain. They felt that money was being thrown into things that lacked any direct economic value. On the other hand, unaccustomed buildings and forms of life might have also scared away the regular clients of the time, for whom Rotermann seemed too elitist and luxurious. Part of this image was surely down to the boutiques that had been opened in the quarter which catered to the wealthy. Nevertheless, as Mänd adds in praise of Rotermann, the focus on the quality of public space and novel architecture has remained consistent from the start. It must be kept in mind that elsewhere, regular commercial architecture still dominated, focusing on maximising the saleable area, and liberally pouring asphalt everywhere. Rotermann should also be commended for having faith in the projects of several young architects.

Some of the first new buildings in the quarter, the so-called City Houses, were designed by AB Kosmos architects Ott Kadarik, Villem Tomiste and Mihkel Tüür. They were still in their twenties when they won the competition. Regardless of their young age, they claim to have been up to the challenge.5 It is likely that they succeeded in the competition namely due to their youth, boldness and clarity of vision—their winning design partly disregarded the 100% building rights given by the zoning plan, and also the detailed plan that foresaw one large building volume for the area. The architects felt that the site needed a more delicate solution, and designed four smaller buildings instead, taking cue from from buildings in the nearby old town and the streetscape of Mediterranean cities.6 Even though they competed in the second round against more experienced 3+1 Architects, and the authors of the detailed plan Aunin and Melioranski, the keywords that they used in their project—plurality of lifestyles, diversity of environment, sustainability, urban density and appreciation of public space—were so intoxicating for the committee that the winner was announced quickly and unanimously.7 Note that from the developer’s side, the committee did not include Sõõrumaa, but rather Märt Vooglaid and Heiki Kivimaa from the management of Manutent.

From the point of view of the entrenched way of life in Estonia, the City Houses are not the best kind of residential real estate, says Mänd.8 At the same time, such a model of downtown development, where location and services are considered more important than parks and playgrounds, is globally widespread. I was able to talk to a couple of early residents of the City Houses who fit this model well—young, at the start of their career, without children and preferring to spend their free time outside the home much time outside home. They were attracted by the distinctiveness and well-considered design of the new buildings—private balconies, lockable street-level spaces for bicycles and strollers, comfortable elevator connections to the underground parking space and waste disposal point.9 They also enjoyed the central location, safety and possibility to live without a car. On the other hand, they bemoaned the mediocre landscaping and poor connectivity of the area. In addition, they particularly highlighted the issue of the commercial spaces on the 1st and 2nd floors of the buildings, where the vision of the developer and of the architects diverged.

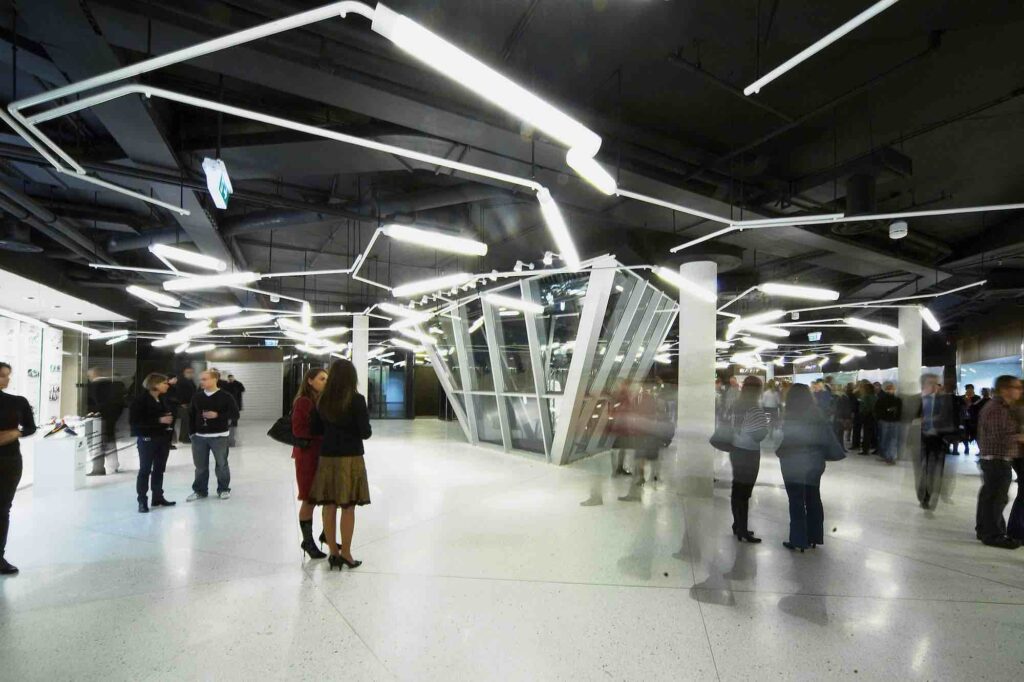

In order to increase the volume of streetward commercial spaces, AB Kosmos architects raised the common area between the four City Houses to the second-floor level. The second floors of the buildings could thus be accessed from the street, and the first floors gained additional volume. The resulting multi-plane landscape associates with the Mediterranean image promised in the competition entry, but it is quite unusual for Tallinn. Raising the surface helped to increase the functional density of the area, and surely also the rental prices of second-floor businesses. But the function and fate of this bulge changed significantly in the course of the design process, when the client wished to add to the initial plan two larger entrances. The idea behind this proposal was to use the first-floor common area to create something like a shopping centre. Tomiste explains that the architects never planned for a shopping centre or mall, but simply apartment buildings and an environment essentially similar to Roosikrantsi street.10 The area, which became known as the Rotermann Atrium, was not embraced by the city dwellers and languished half-empty for years before it was repurposed. Scarcity of commercial spaces, lack of choice and the recession certainly played a role. Furthermore, nearby Kaubamaja, Viru Centre and Norde Centrum (today Nautica) were more clearly defined as shopping centres. Today, one of the entrances has been closed and the other leads to a gym that now fills the former common area. The rest of the entrances to commercial spaces are where the architects initially envisaged them to be. According to Tomiste, all this fuss in the intermediate years might have been skipped if only the client had trusted the architects more.11 There have been several other similar lessons over the course of the development of Rotermann.

Failures and fixes

Rotermann is a fitting poster boy for the daring reconstruction of limestone-built industrial heritage—a good place to bring foreign guests when introducing them to the city. Its location between the city centre, old town and port also makes it an ideal area for guest apartments. And yet, ordinary citizens of Tallinn still do not find their way to Rotermann very often. According to the residents and the architects, this is due to three specific reasons—the focus on consumerism, mediocre public spaces, with little greenery and few options for sidewalk life as described by Jane Jacobs, and poor connections with the rest of the city.

Optimism is, of course, the engine of capitalism,12 and we certainly cannot accuse the developer of Rotermann of pessimism. Nevertheless, time and shifts in the economic situation have made their corrections to retail in the Quarter, and boutiques are today complemented by fast fashion and streetwear stores. Fore example, the luxury watch shop in the southern end of the Orange Building has been replaced with a cafe with views onto the area’s main square. Anticipating that the initial plan might fail, the architects prudently placed a 1×1-metre chimney there, running through all the floors, so a kitchen could be built if needed.13 The image of Rotermann is slowly becoming less elitist and more accessible, but its general reputation is still tilted towards consumerism. There are few opportunities for sidewalk life: improvising and just idling. The latter kind of Telliskivi-like flavour was best represented in Rotermann by the cafe-club Protest, which had the semi-serious motto ‘live and let live’. Protest itself did not get to live long, however, and the building of the club was demolished in 2016. Today, it has been replaced by Metropol Spa Hotel, which was developed by AS Landeste.

The network of public spaces in Rotermann improved significantly with the opening of Stalker passage, and the breach from there to Hobujaama street. This led to more internal connections, different passages and avenues of exploration of the narrow streets. Unlike with the former shopping centre, life is no longer concentrated indoors, and more functions are left to public spaces. The cafes of the passage have begun to extend the terrace season with outdoor heaters. Aavo Kokk, the chairman of the board at U.S. Invest, has noticed that by a lucky coincidence, the glossy facade of the newly completed Ajamaja also reflects more daylight there. This cosiness has not yet been reproduced in the main square of the quarter, which still feels like a sparse thoroughfare or backyard of the cinema. The bleakness is amplified by exposure to wind and a lack of permanent landscaping.

In the early years of the development, some bushes, patches of grass and spontaneous urban vegetation could still be found between the buildings, but most of it has been rooted out by now. Over the years, there have been attempts to add value to the square with various events and design solutions, including artificial grass. Although the main square is on municipal land, it is administered by U.S. Invest, just like several other public areas in Rotermann. Kokk explains that permanently landscaping the main square is complicated by the fact the whole area under the pavement is a car park, which makes it difficult to plant any greenery. Although cars have been banished underground, the square still bears the consequences of the choice between parks and parking. In order to make the square more cosy, there is a plan to further develop seasonal landscaping in containers, including potted trees According to Kokk, they have considered larger plants like blossoming cherry trees, but have been hindered by the lack of necessary expertise in Estonia.14

The yearning for greenery was also mentioned by the residents of Rotermann, who found that there was too much paving.15 On the one hand, the cube stone, which has been massively used in the quarter, is another quality mark of Rotermann—especially considering that most footpaths in Tallinn are still made of asphalt. On the other hand, it was soon realised that cube stones are not very user-friendly in large surfaces—they are uncomfortable to walk on with heels or crutches, as well as for strollers, wheelchairs and bicycles. Square-side cafes have preferred to place terraces on the cube stone paving so your chair would not rock when you sip your cappuccino. The mistake gradually dawned on the developer, and the main movement routes were paved with granite slabs instead. The cube stone islands still left in the quarter could be good places for experimenting with greenery in the future—and why not also with curated biodiversity?16 But since we are talking about municipal land where the building rights are rented to the developer, the city itself should also take a stronger stance in regard to landscaping requirements—especially considering that in other places, the developer has been allowed to fully build up the plots.

Rotermann’s problems with mobility also present a role and opportunity for the city. The connections of the quarter have been pushed to its edges at Mere, Hobujaama and Ahtri street, which are hard to reach for the pedestrians. Architect Tomiste adds that these few access points have turned into cargo loading and waste disposal sites, which renders them similar to the unpleasant backsides of supermarkets.17 Approaching from the port, one needs to negotiate several traffic-heavy crossings on Ahtri street. Access to the old town is available only from the corners of the quarter. Tallinn’s Main Street project, which was supposed to enhance the connections from Narva street and Viru Square, was shelved by the city so it could continue its focus on creating car-centric rather than human-centric spaces. There is still some hope that the project will be revived during the term of deputy mayor Madle Lippus, the former head of the ‘Living Street’ initiative.18 The connections of the area might also be improved by the planned tram line between Vanasadam and Ülemiste, but in spite of several written suggestions, a stop for the Rotermann Quarter is not included in the plan.19 The developer is not sitting idly, however, and is already planning the next building on the edge of the quarter, which could become the new golden gate to Rotermann.20

Mere buildings do not amount to a city

The development of the Rotermann Quarter has in many ways been emblematic and revolutionary in Estonian urban design. The radical land reform of the 1990s put many plots that were important from the urban planning perspective into private hands, so the zoning plan for Rotermann was a significant step towards long-term spatial planning. Architecturally, the quarter is exceptionally dense and varied. Certain eclecticism comes from the fact that the area has been developed in a piecemeal fashion for over two decades. Kokk sees it as an advantage over the usual district development projects, which tend to be built all at once, and where the result can appear artificial regardless of all the effort.21 Even though the initial zoning plan has been largely observed, the architecture of the more recent buildings in Rotermann is creepingly commercial, and less and less worthy of introducing to foreign guests. On the other hand, we should commend the courage of the developer as well as the heritage board to experiment with new forms, which have today become Estonia’s calling card in the world in terms of repurposing industrial heritage. Mänd adds that one of Rotermann’s greatest contributions to Estonian urban development has been proving that car-free spaces are possible when you bring enough density and added value to the public sphere.22 Unfortunately, these principles have yet to be adopted more widely in the city.

Rotermann also teaches us that sumptuous buildings do not yet amount to a city. In order for the residents to feel at home, and the visitors to feel welcome, the public space between the buildings must offer basic amenities that are not purely premised on consumption. Shops and services are also necessary elements of the urban space, which serve as destinations for visitors. But the basis of any sustainable long-term planning must be a well-considered mobility plan and the potential for spontaneous street life. The relation between the developer and the municipal government in developing the city is also something that needs further consideration. There is not much municipal land in Tallinn, but even this little has often been sold to developers without any guidelines in terms of social beneficence. It is high time to shift our focus from our personal lives and wealth to appreciating biodiversity, and to learn from the plants, animals and people besides the consumers who are all important participants in any sustainable urban environment. Live and let live.

MATTIAS MALK is an Estonian urbanist, co-founder of the Urbiquity project, lecturer at the Estonian Academy of Arts and freelance photographer. He divides his time between Tallinn and Munich. He is currently working on his PhD thesis in the Faculty of Architecture at the Estonian Academy of Arts, which focuses on mobility and infrastructure, and more specifically on the development of Rail Baltic.

HEADER: view of the square at Rotermann Quarter. Photo by Kaupo Kalda

PUBLISHED: Maja 108 (spring 2022) with main topic Opening Tallinn to the Sea

1 Epp Lankots, „Kellele kuulub Rotermanni kvartal“, Postimees, 20.03.2002, https://arvamus.postimees.ee/1928385/kellele-kuulub-rotermanni-kvartal.

2 Martin Melioranski, „Rotermanni kvartali kirdeosa detailplaneering“, Maja, 2-2003.

3 Andres Kärssin, „Rotermanni ehituskava tõi kaasa protestid“, Delfi, 12.03.2002, https://arileht.delfi.ee/artikkel/3251729/rotermanni-ehituskava-toi-kaasa-protestid?.

4 Endrik Mänd, in conversation with the author, 17.03.2022.

5 Villem Tomiste, in exchange with the author, 17.03.2022.

6 ibid.

7 See: Kalle Komissarov, „Rotermanni saaga“, Maja, 2-2005.

8 Endrik Mänd, in conversation with the author, 17.03.2022.

9 Two early residents of Rotermann in exchange with the author, 03.2022.

10 Villem Tomiste, in exchange with the author, 23.03.2022.

11 Villem Tomiste, in exchange with the author, 17.03.2022.

12 Daniel Kahnemann, Thinking, Fast and Slow (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2011).

13 Villem Tomiste, in exchange with the author, 17.03.2022.

14 Aavo Kokk, in conversation with the author, 22.03.2022.

15 Two early residents of Rotermann in exchange with the author, 03.2022

16 Tartu 2024 – European Capital of Culture project, which is led by landscape architects Anna-Liisa Unt, Karin Bachmann and Merle Karro-Kalberg.

17 Villem Tomiste, in exchange with the author, 17.03.2022.

18 Marko Tooming, „Tallinna peatänava projekt saab edasi liikumiseks töörühma“, ERR, 12.03.2022, https://www.err.ee/1608501893/tallinna-peatanava-projekt-saab-edasi-liikumiseks-tooruhma.

19 Mattias Malk, „Avalik arutelu Tallinna moodi“, Sirp, 21.01.2022, https://www.sirp.ee/s1-artiklid/arhitektuur/avalik-arutelu-tallinna-moodi/.

20 Priit Liiviste, „Ahtri tänavale arendatav büroohoone saab nimeks Golden Gate“, Pealinn, 02.02.2022, https://pealinn.ee/2022/02/02/ahtri-tanavale-arendatav-buroohoone-saab-nimeks-golden-gate/.

21 Aavo Kokk, in conversation, 22.03.2022.

22 Endrik Mänd, in conversation, 17.03.2022.