SAUE TOWN HALL

Location: Kütise 8, Saue

Architecture: Karli Luik, Johan Tali, Mae Köömnemägi, Heidi Urb / Molumba

Structural design: Laur Lõvi, Triin Sigus / Makespace

Interior architecture: Eeva Masso with Katrin Tammiksaar, Jaana Albert / EEOO Studio, Molumba

Landscape architecture: Molumba

Landscaping: Maarja Gustavson / spatial design consultancy Polka

Special parts: O3 Technology

Construction: Embach Ehitus

Client: Saue Vallavalitsus

Total area: 1300m2

Competition: 2017

Project: 2017–2019

Completed: 2020

Nominee of Cultural Endowment of Estonia in architecture 2020.

Each public competition and design carries in itself both potential and responsibility to make a contribution to the spatial environment surrounding the building.

When entering the new town hall of Saue, the anonymity that one normally experiences in public buildings is stripped away. The global pandemic restrictions require the identification of all visitors. Making everybody’s town hall experience even more relaxed and intimate, everyone is wearing only socks or slippers indoors. The no-shoe policy which the building’s denizens have collectively agreed upon appears to be motivated not by the fear of dirty boots soiling the new carpet, but by the desire for comfort and cozyness—it is the people who have the power over the building and not the other way round.

Perhaps there are others like me who, while observing the photos of the new town hall of Saue, have been struck by the building’s outward majesty—its distinct simple geometrical shape, its symbolic significance, its peculiar but nevertheless imposing colonnade. Yet during my visit to the building, the qualities that came to the fore were of a different sort. The town hall appeared to be exactly of the right size, designed to meet the needs of an office building perfectly, and having a lot of activation potential for further generation of urban space. So, what is the role of an architect in the processes leading to these results? Can we suggest that, perhaps, the architects might benefit from the adoption of a specific conviction or philosophy to drive their work in all aspects, to ensure that they do not run out of steam and inspiration before the end and always see their vision to completion?

Fit-for-purpose design

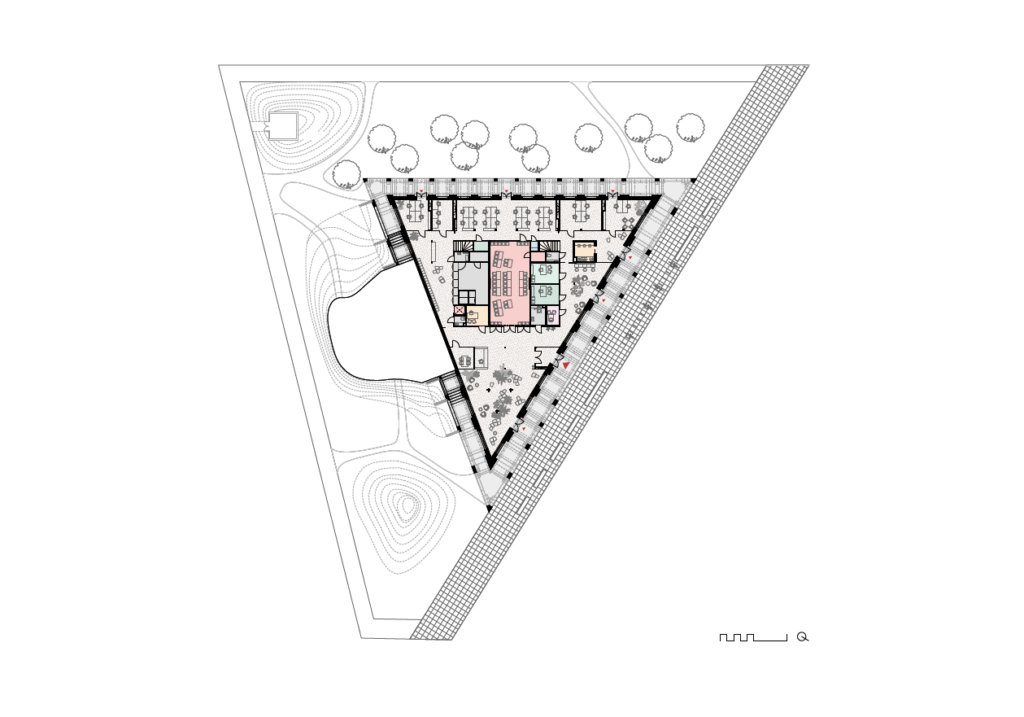

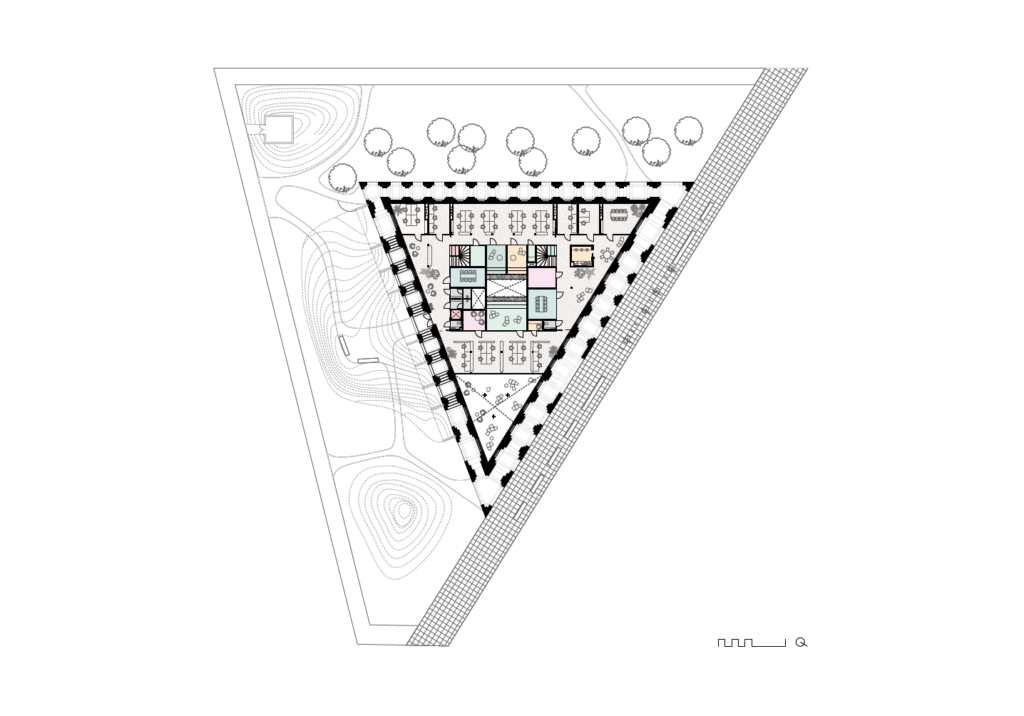

The primary and fundamental purpose of the new town hall, of course, is to be the workplace for the roughly 80 public officials of the town of Saue and the rural municipalities of Kernu, Nissi and Saue that were merged in 2017. Already in the initial phase of the architectural competition, the participating architects were instructed to be ‘contemporary’ in their approach to the working space design, and the solution put forward by the architecture office Molumba was built around the concept of activity-based open-plan office space. Certainly, the idea of open-plan office is hardly new in the 21st century, but ingenuity is to be found in the execution of the building’s floor planning. What stands out is not the novelty aspect, but exceptionally balanced and functional planning that makes the most of the available indoor space without any undue compromises, regardless of the unusual triangular shape of the building itself.

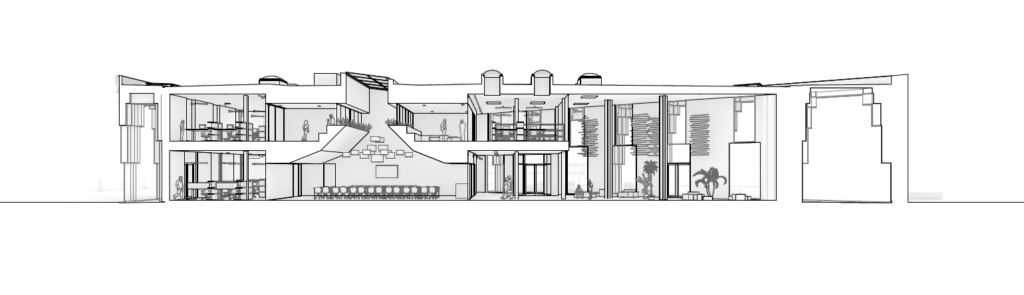

The architects claim to have drawn inspiration for their solution from a common and reliable logic of office planning.1 The arrangement of rooms is based on a simple pattern which puts a rectangular core containing all smaller ancillary rooms, such as toilets, meeting rooms and quiet rooms at the centre of the building’s triangular outer shell. The space between the core and the external triangle is allocated for open-plan offices, shared spaces and the public area. The building’s otherwise simple interior, however, makes a single grand architectural gesture in the shape of the red council chamber at the very centre of the building, spanning across two floors. The room is rather daft, not over the top, and has a cool vibe. Upon entering the chamber, the room cuts through both floors and reaches the skylights in the ceiling, thus providing a vertical church-like contrast to the horizontal plane of office space.

What ‘activity-based’ here means is the absence of permanent workplaces and the freedom to switch from one work desk to another, depending on the project and the team one currently participates in. As I was informed by the head of management and the mayor, the work desks are organised in groups which are attached to specific departments and can serve eight individuals at most.2 So far, most municipality officials have decided to stick to one work desk only. Their choice is rational and does not undermine the idea of the activity-based office space in a longer term, since the town hall office is free of hierarchies and if warranted by any new activity, can be reorganised quickly and effortlessly. There are no cumbersome complications which the officials themselves would have to solve with various ad hoc methods. Such a flexible solution has proven its worth especially well in the context of the pandemic restrictions, which, perhaps, in itself is the best testimonial of its attunement to contemporary trends.

Personalities

Koit Ojaliiv, in his article on Saue town hall that was published in the Estonian cultural weekly Sirp in October 2020, quoted the words of Leonhard Lapin who saw the greatest problem of architecture both in Estonia and abroad as that of abscence of great personalities. As a praise to Molumba office who designed the new town hall of Saue, Ojaliiv then observed that the lack of personality or character is certainly not something that Molumba architects suffer from.3 To me, however, such an admiration and yearning for ‘great individuals’ associates with an unhelpful egoistic practice of the past which should be abandoned. If we do this, we will no longer be blind to the exploitation of other people’s work and to the fact that most ‘great artists’, to produce their work, rely on the help of numerous dedicated people who surround them. We will also be able to have a more long-lasting and positive impact on the society and environment. It appears to me that the great individuals in architecture truly succeed only when they refrain from using their social privilege and personal charisma to rise to the podium, but are willing to put their intellect in a more selfless service that benefits everyone. This would presume an ability to listen to the future users of the project, to realise and acknowledge the contribution that is made by the other parties in the process of co-creation, to involve the clients in such a manner that they also have agency over the building’s spatial design. The myth of an artist-architect whom the client perceives as having no sense of reality, but who in their exalted mind knows themselves to be just too intelligent for the client to understand is there to be broken. Ojaliiv’s words in Sirp made me think of how the presence of Molumba architects’ personalities could be felt when I visited the town hall and what possible roles they could have played in the wider processes that led to the final realisation of the building.

My tour guides in the town hall, Head of Public Relations Sirje Piirsoo, Mayor Andres Laisk and Head of Management Silver Libe were certainly aware of their contribution and responsibility in making the idea of the building a reality. Such a positive and proactive attitude on the part of the client is commendable—one’s responsibility is willingly assumed. My hosts spoke of their collaboration with architects as of a mutually pleasant and beneficial experience, conveying a sense of respect. Not once during my visit did I notice them doubting in any of the spatial decisions that had been made or using jargon with no bearing on reality in their descriptions.

The client’s awareness and the formulation of the competition task which both the town administration and the Estonian Association of Architects worked on certainly benefitted from the earlier conceptualisations of Saue’s town centre that had been put forward before 2017. In 2014, a town-commissioned report had come out after 18 months of prior work by Urban Lab and Väike Vasak Käsi OÜ to offer a vision of the future town centre.4 This was achieved in a novel co-creation process involving the town administration, the land owners and the townspeople, with one of its central being the empowerment of all interest groups and their engagement in a discussion. The vision was finally distilled into a zoning map of the town centre, intended to serve along with the report as a basis of a future detailed plan. The research completed by Urban Lab is a useful information layer, primarily as a process of raising spatial awareness that the town administration and the townspeople had already undergone before the architectural competition of 2017.

Somewhat surprisingly, no-one was invited from Linnalabor to serve on the panel of the design competition of Saue town hall.5 However, the judges did include Egon Metusala whose team had been responsible for the design proposal that had received the purchase prize in the 2016 design competition for the town centre of Saue.6 Thus, the expertise of the architects who had been involved in the earlier conceptualisations of the area was still represented among the panel judges.

Molumba’s design arose in the context of a larger network of processes. I find it remarkable that the work of Molumba architects has been successful in bringing together different interest groups, giving reasonable consideration to earlier planning work, with all coming together in a well-functioning building and its environment which takes account of possible future spatial developments. The architects’ triumph, in this case, lies in their abandonment of purely self-serving practices—without the dilution of their proposal’s central idea to spatial mediocrity .

Ideas

Returning to the question of the greatest problem in contemporary architecture, I would rather suggest that it is the shortage of great ideas and not of great individuals that architecture suffers most from. It is not important if these ideas are born out of individual, community or group efforts, or in any way conceivable. The truth is that each public competition and spatial design carries in itself a potential, or even responsibility, to accomplish something constructive to benefit the spatial environment even beyond the borders of the planned building. For that, we need the ideas that would amplify the significance of the design from that of an inert object to that of a potent space, invested with agency.

The forays of Estonian architects into diagram architecture, such as popularised by MVRDV, or also by BIG, in general remain very much focused on buildings. The minimalist architecture of simple forms that gained momentum in the Netherlands in the 1990s was, among other things, motivated by the desire to make the publicly funded architecture more comprehensible to the general public. However, in 2000s, the Danish architecture office BIG took the idea to the extreme by reducing the spatial design to a linear communication flow. Usually, these designs relate to their environment only superficially and have little regard for the existing space, hiding their vanity behind the argument of the ‘grand idea’. The ‘grandness’ of the idea is normally limited to upscaling a tiny simple geometrical form to a building-sized physical counterpart. Relishing the metaphor, rather than considering the spatial reality, the designs aim to create architectural icons—an upside-down U-shaped building, a house shaped like a ski hill, a W-shaped building, buildings raised on stilts, etc.

My visit to Saue reminded me that a sensitive treatment of a simple geometrical shape can be achieved. One of the tasks which the architects were entrusted with was to organise the spatial structure of the town centre and the application of a clear form is a good idea in an otherwise messy and chaotic town centre. Too many untied knots still remain to know for sure the direction which the development of Saue’s town centre will take, but the new town hall will certainly serve as an excellent focal point for different possible solutions, supporting connections to more distant key places, such as Saue train station and Saue manor (and the manor park) as well as to closer ones, such as the central park and the industrial district in central Saue.

The second central idea is the use of cross-laminated timber as a primary construction material. The choice of materials is frequently included in the architectural design only as the author’s aesthetic preference, or in a better case, also in consideration of possible tactile experiences. However, bearing in mind the extensive environmental impact of the construction industry, it is clear that in the 21st century the choice of construction materials should be a factor of fundamental importance that shapes the design/project from the outset.

Molumba architects had already proposed a cross-laminated timber structure with relatively good CO2 parameters in their initial competition design and thereby the idea was successfully planted in the heads of all involved parties already early on.7 The idea blossomed into a vision that was certainly worthy of the attention of the construction company Embach, gluelam producer Arcwood, not to mention the architects themselves and the client, the town of Saue who had assumed a strong public trendsetter role. It certainly favours the completeness of the building’s realisation that the material itself also shaped the building and amounted to much more than a mere afterthought.

Conviction

However, something appears to be lacking in the final design to be entirely convincing. Nothing is exactly wrong, but the powerful gesture made by the masterful floor planning is slightly diminished by the somewhat aimless interior architecture and by a couple of sloppy details, such as the rough unfinished edge of a CLT ceiling panel appearing in the window. It looks like the design team had finally run out of steam, right before the finishing line. Paying equal attention not only to the general plan of the building but to details as well is important for ensuring the success of the final execution of the idea. Otherwise, the idea remains not fully realised, lending itself to attacks more easily and more likely to decline quicker.

What I mean here is not only taking a more pronounced interest in specific detail solutions which many architects claim to have not much care for, but also the completeness of the entire solution, since any shortcomings in that regard can mar the overall impression. This, on its turn, is a threat to the longevity of the building—the so-called broken window effect8 is caused by very small things that can lead to enormous consequences. Why this kind of completeness has rarely been achieved in Estonia can be blamed on a complex set of reasons and a part in it has certainly been played by the architect, builder, client, dominant market conditions, insufficient resources, etc. For the sake of provocation, however, I also suggest the absence of an underlying conviction or philosophy as an important contributing factor.

Molumba designs appear to share certain common qualities with the designs of Belgian OFFICE Kersten Geers David Van Severen. Both teams are notable for their fondness of architecture that is reduced to simple geometry. Leaving this speculation as it is, I would like to point out the self-descriptions of both offices on their respective websites. Molumba keeps it short and simple: ‘Molumba is an all around architecture office from Tallinn’.9 OFFICE makes a longer statement: ‘OFFICE is renowned for its idiosyncratic architecture, in which realisations and theoretical projects stand side by side. The projects are direct, spatial and firmly rooted in architectural theory. The firm reduces architecture to its very essence and most original form: a limited set of basic geometric rules is used to create a framework within which life unfolds out in all its complexity.’10

The punk ambivalence or the eloquent articulations on the website may do not necessarily capture the whole reality, yet they nevertheless constitute a public position taking. I suggest that it is clearly apparent in the KGDVS designs that they rely on a reference system of their own making, a philosophy or even ideology which guides their designs regardless of their scale or their prospect of becoming built. I draw attention to this distinction and challenge the public for discussion: if Molumba designs were inspired by a specific conviction or philosophy that informed both the general activities of their architects as well as this particular design, would they have achieved a truly complete solution where the same ingenuity that is present in the general planning is also to be found in smaller details?

Success story

Saue town hall is indeed a success story of the Estonian architecture of this decade in more than one sense. The building is notable not only as an architectural object, but also as an element in a larger urban design scheme that both shapes and takes account of the future. The success story is also to be found in the contemporary approach to construction material— promotion and popularisation of the use of cross-laminated timber as a construction material is by itself a challenge enough. The initiative shown by the local authorities is also impressive, as is the tight-knit teamwork that produced those excellent results. Molumba architects do not engage in self-absorbed pursuits, but are spurred by the ideas of meaningful spatial design. It is with excitement that I will continue to observe how the now well-established office will choose to use these capabilities.

LAURA LINSI engages in architecture and spatial production by designing, writing articles, supervising students and carrying out research projects. She is one of the founders of the LLRRLLRR studio.

HEADER photo by Tõnu Tunnel

PUBLISHED: Maja 104 (spring 2021) with main topic What’s happening?

1 Based on the phone conversation with Molumba architect Johan Tali, 11 March 2021.

2 Based on the conversation with Mayor Andres Laisk, Head of Management Silver Libe and Head of Public Relations Sirje Piirisoo, 4 February 2021.

3 Koit Ojaliiv. Iseloomuga tegelane [‘Someone with Character’] in Estonian cultural weekly Sirp, 23 October 2020.

4 More information regarding the work of Urban Lab on the town centre of Saue can be found on its website: http://linnalabor.ee/sauekeskus/ (in Estonian). The final report (in Estonian) can be downloaded from: http://www.linnalabor.ee/failid/n/1f3d2a115a5a1a686569c6d440aed1ad.

5 According to Kristi Grišakov (Vasak Käsi OÜ) and Regina Viljasaar (Urban Lab), whose brief comments on the matter were communicated to the author by Keiti Kljavin (board member of Urban Lab), 1 March 2021.

6 A depiction of the submitted design proposal is available on the website of architecture office MA (in Estonian): Town centre of Saue, architectural design competition, 2016, purchase prize. Authors: Liis Uustal, Pelle-Sten Viiburg (Doomino Arhitektid OÜ). https://www.abma.ee/Saue-linna-keskus.

7 Based on the phone conversation with Molumba architect Johan Tali, 11 March 2021.

8 The ‘broken window theory’ posits that the small bits that are broken or in disrepair can trigger a quickly escalating large-scale breakdown of order.

9 https://www.molumba.com/about

10 http://officekgdvs.com/about/