I last visited Riga right before COVID-19 swept over the globe taking all meetings to the virtual space. All borders were suddenly closed and we only heard about the life in Latvia through our public broadcasting reporter Ragnar Kond in the late night news programme.

During that last trip to Riga, I noticed spirited landscape architecture in the generally quite chaotic street setting of the capital of our southern neighbours. When taking a closer look, it all seemed to be originating from the same office–landscape architecture office ALPS founded by Helēna Gūtmane, Mark Geldof and Ilze Rukšāne.

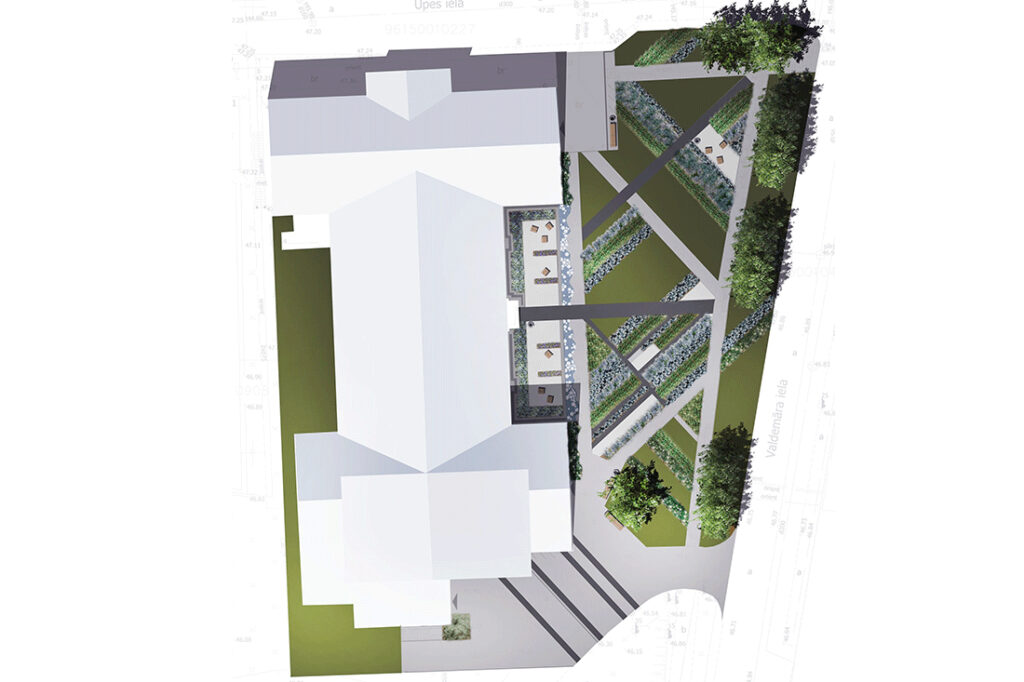

My first impressions of their work came from the outdoor area for New Teika district. It is a commercial and residential district with the landscape around the buildings turning the otherwise bleak environment into a favoured place to live and work in. New Teika appealed to me with its elaborate (small) details as well as its spaces of varying nature that were mostly brought out by the skilful use of landscaping materials. After my trip to Riga, I kept seeing more and more works by ALPS in my social media feeds: competition entries superbly capturing the natural surroundings, projects aimed at turning important streets in Riga (and elsewhere too!) into pedestrian-friendly environments, sensitive courtyards around apartment buildings and playful public spaces. All marked by excellent designer work while remaining socially sensitive and enviably rich in landscapes. However, landscape projects are not the signature move of ALPS, they also focus on community activism and strategic urbanism. At the time of the interview in early summer, they were busy with creating a community garden and reorganising one of the most important arteries in the centre of Riga as a temporary leisure area.

There are altogether 15 employees in the office, qualifying as a huge office in the Estonian sense. In addition to landscape architects, the team includes an architect-urban planner-urbanist, landscape contractor and illustrator. A separate team is put together for each project with one of them focussing on the big picture, one on details, one on feasibility etc.

It seems that the success of the office relies on its diversity. Helena has studied not only landscape architecture but also philology and philosophy, Mark is an architect and urban planner from Belgium and Ilse is a landscape architect advocating the healing properties of landscapes.

We are discussing landscape architecture with Helēna Gūtmane, Mark Geldof and Ilze Rukšāne online although I initially planned to go there and visit their works together with the authors. In addition to Helēna, Ilze and Mark, also the senior landscape architects Indra Ozoliņa, Mētra Augškāpa and landscape architect Sendija Adītāja joined our discussion around the table (and behind the screen).

Let’s start from the very beginning. How did you start the landscape studio ALPS? How did people with such different backgrounds end up together?

Ilze Rukšāne: There was an architecture competition for Riga Botanical Gardens in 2007. I saw the work by Helena and Mark and I recognised something in it. They had a contemporary broad and social view of the space and the ability to solve bottlenecks on large scale. I heaved a sigh of relief as I had finally found somebody who thinks the way I do. I had a feeling that people tended to have a very narrow approach to landscape architecture and consider it as horticulture. Mark and Helene’s attitude to landscape and public spaces was not stuck in one discipline. They showed how a botanical garden can bring together people from all over the city and it can be turned into a community space.

Helēna Gūtmane: In Latvia, as probably also in Estonia, landscape architecture is a relatively new speciality. Its instruction was revived in the Latvian University of Life Sciences and Agriculture only in 1995. There has been a lot of soul-searching: is it something between horticulture and architecture, or what does a landscape architect do exactly? We could say that Mark brought urbanism to Latvia, something that we all lacked. We never thought about mobility, how to plan it, how to make the city function as a whole, what public space is, how to communicate with other stakeholders of the space such as property owners. Mark was and still is our teacher, he showed us how to approach a city that is such a complex phenomenon full of various processes.

Ilze Rukšāne: I was also fascinated by their metaphorical approach. Metaphors are similarly important when talking about landscapes, spaces and places and Helena could translate words into landscapes and spaces.

Helēna Gūtmane: I have studied also philology and philosophy and so thinking in metaphors comes naturally to me. When I look at a landscape, I tend to think in images. Mark gave us the tools how to turn words and metaphors into spaces.

Mark Geldof: I began working in Latvia already in 2003 when I consulted local governments and dealt with issues of regional planning. At the time, planning was taken as zoning in Latvia, my colleagues and I had to work hard to make spatial planning more strategic. Similarly, detail plans were too much concerned with defining zones. Even today, I think detail plans are too concerned with details and too complex compared to Belgian practises. We should ask if it is all necessary. We do not need to define all details, especially in a situation where the given details tend to change very quickly.

How has your approach to landscape architecture changed over the years at ALPS? You mentioned earlier that landscape architecture used to be taken as horticulture, just garnishing and decorating with greenery rather than public spaces or urbanism. This has been the practise also in Estonia. When did it all change in Latvia?

Ilze Rukšāne: It seems that it is still an ongoing process. Landscape architecture was actually in a good situation during the Soviet period. Once the Soviet Union collapsed, there seemed to be some confusion. They did not know how to set goals: in what direction should they go and how should they think about landscape architecture. Many people asked why we need landscape architecture in the first place, does it give any added value or is it merely a waste of money. When I look back now, I see that these doubts have not disappeared but there is definitely more appreciation for public spaces.

The first big step towards changes came with the economic crisis in 2008. After the crisis we saw how the projects we had designed in 2006 came to be constructed. When something is realised, you can actually experience the space and see how landscape architecture can make environments considerably better. Once they see that it is much better than before, they can and want to commission similar projects also in the future.

COVID-19 pandemic marked a similar turning point proving once again that well considered public spaces and outdoor areas contribute immensely to the quality of life in cities and relieve tension. We also see how important spaces of various scales and functions are: large and small, intimate and public, places for seclusion and gathering etc. Also real estate developers now appreciate outdoor spaces as valuable additions to the living environment. Local governments require that projects include a landscape architect. Ten years ago, it was primarily about buildings and it was assumed that spaces are created by architects. Nevertheless, I think that we are about 10-20 years behind Belgium and Mark’s experience.

For instance, we truly lag behind in road construction. Roads play a considerable role in the environment, however, road engineers design them without landscape architects. Legislation and regulations do not include the concept of a landscape architect, officially only road engineers can design parks.

Indra Ozolina: 15-20 years ago, I was one of the few landscape architects who worked for an architecture office. At the time, landscape was the last thing to be constructed, if at all, as usually they ran out of money at this stage and I often did not see the realisation of my work. This has changed now, however, coming from the Soviet times, we still tend to appreciate the personal space more and thus leave the public space in the shadows.

Metra Augskapa: When I began my studies in landscape architecture ten years ago, the speciality was still considered mainly as horticulture. What I was taught is very different from what I do now.

Despite the difficulties you describe, your portfolio still includes a pretty impressive number of projects. What do you think is the secret of your success?

Ilze Rukšāne: It is the magic of teamwork and hard work. We believe in teams, I like to think of APLS as the dream team. Public space projects include a project manager responsible for meeting the deadlines and assigning tasks, a leading landscape architect and a landscape constructor. If needed, we also involve mobility experts, sculptors, engineers etc.

We also enjoy participating in architecture competitions. It helps to maintain creative freshness that tends to wear off with pragmatic commissions. This year we have also had several environmental art projects that are particularly interesting as they make you think about landscapes from a new angle and you need to think how the landscape can highlight the work of art. Cooperation with artists is naturally an enriching experience.

What is the underlying concept of your work?

Ilze Rukšāne: I believe that many of our works are based on the principle of healing landscapes, combining the spatial and social aspects. Healing gardens are usually designed to be perceived by all senses, we add our own nuances: memories both in the direct and figurative sense of the word, balance and proprioception, that is, the perception of the body or muscle sense. Spaces need to be designed in a way that their users have options–either to move forward or stop, meet others or withdraw. For instance, small alcoves for sitting apart from others or larger pockets for gathering together. Another important feature is safety, both mental and physical. Spaces must not confuse you but give clear signals of what is happening and where you should go.

We are currently cooperating with the psychiatric centre in Riga, however, we implemented similar principles, spatial solutions and plant selections also in the New Teika project.

Metra Augskapa: We design for people. Also when designing the environment of commercial districts, we do not think of businessmen but people in general. We try to take the best features of the landscape and interlace them with its healing properties.

Helēna Gūtmane: Landscape architects are often like doctors–we do not heal people and we do not eliminate viruses from the world, but we do have the tools to create spaces for healing. Especially for mental healing.

Here also the social aspect plays a considerable role, how the space can bring people together. We have conducted workshops that draw neighbours together and we are happy to see that they still come together and active neighbourhoods have given rise to spatial activists. We are currently the only Latvian landscape architecture office that works with all stakeholders, including businessmen and children, by means of systematic inclusion and participation, in other words, we want to make sure that the spatial project is not only about renewing and reorganising the space but also a tool for activating the residents and creating a network.

Ilze Rukšāne: It seems to me that we all have this need to do social work, that is, to do unpaid work. During the Soviet period, we all attended subbotniks, so contributing to social welfare seems to be an innate need. And not only for the older members of the office but also our younger employees tend to be active citizens. This is something that encourages our team, brings us together and sometimes even lights up our eyes more than the paid work. Such projects tend to have a very long and lasting impact: you have the chance to meet people that you would otherwise never interact with and such meetings are always warm and refreshing. For instance, we are participating in the revival of Rotermann Quarter in Riga by promoting a community garden project. People who first met there now wave and smile at each other in the street. They used to be strangers to one another.

Landscape architecture has become very normative: there are strict rules about streets, playgrounds and public spaces that should primarily serve the function of user safety but at the same time make environments repetitive and even boring. When you ask the users what they would like to do in the outdoor space, it is clear that their wishes vary from one end of the spectrum to the other, starting from new fountains to no change at all. How do you maintain your creative freshness in the context of such prescriptions and multiplicity of wishes and stakeholders, how do you create landscape architecture that still entails a higher artistic output?

Indra Ozolina: It comes with experience. We learn from every project and the more we design, the smarter we become. Young people come to our office usually with crazy ideas and non-existent experience. It can all be daunting and scary at first, but fresh and crazy ideas are actually refreshing. Even if you cannot implement them immediately, they will linger on in your subconscious, perhaps in the form of a detail, and might influence your next project.

Metra Augskapa: It is about balance and teamwork. If you have team members with various skills and knowledge, then also the solutions are more balanced and versatile. One of you checks the regulations, one deals with inclusion and co-creation, one works on the concept, one sees the big picture and one has the knowledge how to build it. All participants play a highly important role in achieving the best result. Similarly, we should not forget that getting an excellent creative solution often requires doing more than asked, going the extra mile.

Helēna Gūtmane: Landscape architects are mediators. We try to listen to the place, understand what the space needs, find a balance between the interests of the stakeholders. This is our strength. You cannot approach landscapes with a big ego and solve situations on the basis of criteria such as ‘I like it’ or ‘I don’t like it’. Every situation is unique and every space requires an entirely personal approach, you need to listen to people, landscapes, rocks, dogs, children, architecture etc. You need to be a kind of space whisperer. You need to listen to all the voices and this is the highest form of art. In case of public spaces and landscape architecture you cannot let your ego dominate the space.

What drives you to act?

Metra Augskapa: Landscapes themselves, their layers and potential. The idea that you can study the space layer by layer and bring out the most important features.

Indra Ozolina: I am inspired by details. Whether it is illusory or something physical in the space. I also try to add some unexpected details in my own solutions.

Ilze Rukšāne: Love. Love is the greatest inspiration. When you see people smile in the space designed by you.

Mark Geldof: I am driven by community, finding and formulating common interests. I am allergic to the arrogance of investors.

Helēna Gūtmane: Harmony. I always look for balance in space.

MERLE-KARRO KALBERG is a landscape architect and the editor of the architecture section in cultural weekly Sirp.

PHOTOS by ALPS ainavu darbnica

PUBLISHED: Maja 105 (summer 2021) with main topic Landscape arhitecture