The Estonian Association of Interior Architects is celebrating its 30th anniversary this autumn. Is Estonian interior architecture only so young?

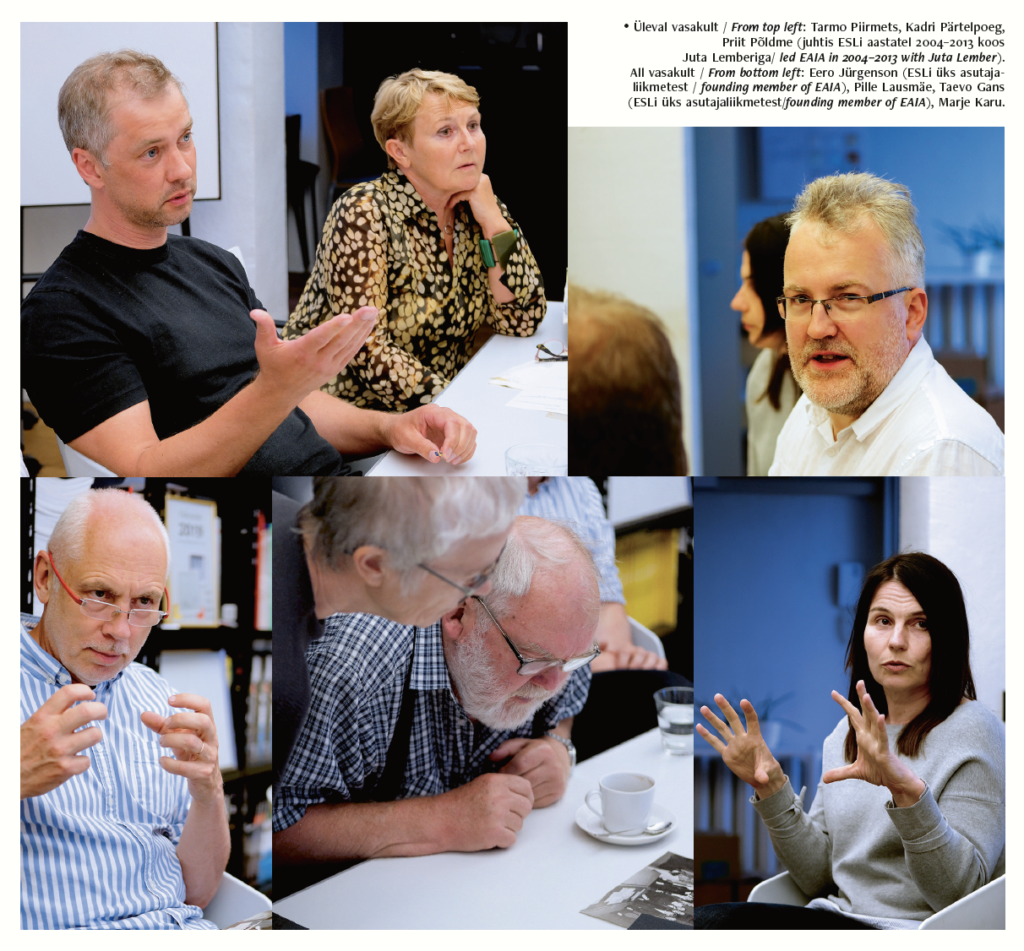

On a July evening, interior architects of various generations Taevo Gans, Kadri Pärtelpoeg, Eero Jürgenson, Pille Lausmäe, Priit Põldme, Marje Karu and Tarmo Piirmets came together at the association’s office in Rüütli Street to discuss the establishment, needs and current issues of the organisation. The discussion was led by Eero Jürgenson.

This autumn the Estonian Association of Interior Architects (EAIA) is celebrating its 30th anniversary. Against the background of grand centenaries, this number shows they have reached adulthood and the organisation has certainly proved its worth.

We can talk about professional Estonian interior architecture already in mid-1930s. Interior architects have been provided higher education for more than 80 years. It dates back to 1938 when the speciality was established at the State School of Applied and Fine Arts.

The post-war generation of interior architects was sturdy, some had begun their career already before the war (Maia Laul and Maimu Plees). One of the first Estonians to be educated as an interior architect was Teodor Ussisoo who later became the head of the State School of Industry. Teno Velbri and Väino Tamm created a comprehensive and professional atmosphere in the department. Having practised in Finland in the second half of 1960s, Väino Tamm returned with considerable experience that came to define the new directions in Estonian interior architecture. It was his experience in Finland that shaped the understanding of interior architecture as we understand it today. Interior architecture projects became more detailed and more thorough. We could say that there was a crucial breakthrough in the project graphics in 1960-1962: envisions and draft ideas (in pencil/ watercolour) were replaced by proper projects.

Before the establishment of the association, interior architects were distributed between the Estonian Association of Architects and the Artists’ Association. The division was based on the type of projects they were mostly concerned with. The applied arts and designers’ sections of the Artists’ Association were joined by those who primarily designed exhibitions and trade fairs while the Association of Architects was joined by those who worked on interior design projects on a larger scale. There were around ten interior architects in both associations. In retrospect we can say that we had in a way two schools of interior architects with different competences—firstly, interior architects who worked for the design institutes EKE Projekt, Tsentrosojuzprojekt and Tööstusprojekt on extensive projects covering the entire Soviet Union and thus communicated with large teams, and secondly, exhibition design creators whose strengths included skilful improvisations and solutions to technical problems.

Why wasn’t the association founded earlier?

In late 1980s, there were so many strong impulses coming from every direction that we felt it was time to do it. The main reason perhaps was the general increasing construction volumes in 1980s. Interior architects had more work, there were more construction projects with greater challenges. This was the time of longstanding unique interiors. Interior architects felt that they had less in common with the artists and thus working under a subsection of the Artists’ Association was considered constricting.

The development of EAIA (and the emancipation of interior architects) was also affected by closer contacts with the Finnish Association of Interior Architects (SIO) in late 1980s that actually had been established already in early 1960s. The Finnish colleagues sincerely wanted to help us and their assistance was gladly received. So, for instance, the Estonian representative was included in the Nordic (Finnish, Swedish, Norwegian and Danish) interior architects’ meeting in Sweden in 1989. The chairwoman of SIO at the time Lena Strömberg is today our honorary member.

We considered our association as a universal instrument allowing us to have a say in public matters, conceptualise the role of interior architecture in the architectural scene and organise events related with the field. The founding members were Vello Asi, Leila Pärtelpoeg, Leo Leesaar, Taevo Gans, Eero Jürgenson, Aet Maasik, Juta Lember, Krista Roosi, Teno Velbri, Rein Laur, Ivi-Els Schneider, Mati Leon, Malle Agabuš and Taimi Soo.

The ESL foundation meeting was a festive event held in the Town Hall on 20 November 1990. What did the foundation of the association change and what were your first achievements?

EAIA immediately became very popular with new members actively joining. There were many trained interior architects who needed information and support regarding the international information space. The association cooperated with umbrella organisations and searched for ways to relate to the society and communicate with the state. When EAIA was founded, both private clients and companies seemed to value interior spaces that created also a new identity, and as a result, numerous high-quality and clearly distinguishable environments were built.

The speed of information flow changed. Thanks to the emergence of EAIA, information on new materials and opportunities reached interior architects more quickly. Many material manufacturers and sellers are still our supporters and through various activities we have jointly contributed to the creation of great spaces over the years.

In this context, a special role was played by the series of exhibitions RUUM & VORM in 1990s founded and mentored by Bruno Tomberg. This in a way became a powerful demonstration of the meaning and creative effort of Estonian interior architecture in a general state of scarcity and shortage. These highly popular exhibitions had a strong impact on the aesthetics of an entire generation, spatial education as well as on the requirements for environment. They also proved that material restrictions should not delimit creativity. As most people at the time still lived in the bleak reality remnant of the Soviet past, high-quality design furniture in this context acquired an artistic air capable of changing the society. The exhibition featured a culture of living that was so different that it seemed to speed up the Estonian accession to the EU even if the political factors predicted the inevitable long-windedness of the given process.

The legislative issues found their way in the EAIA agenda in the second decade. In the early years there was no such thing as regulation by law, not to mention over-regulations as we commonly understand the notions.

How does EAIA present the role of interior architecture? Which interiors have acquired a symbolic or landmark impact?

From the very beginning, interior architects considered architects as their key partners. In this tandem, interior architects are responsible for the human scale: solving those interior details that people are immediately surrounded by in their daily activities.

The most visible and lasting example of our promotional work is the annual award series with its history extending over 40 years (reportedly among the longest running design awards in Europe). The image and media coverage of this event have become increasingly important over the years.

The annual award nominees primarily include environments that are relevant in their time and predict imminent changes in the society. Good interior does not merely follow the global trends—it relates to them locally by generating wider discussion in the society on values that find expression in people’s changing lifestyles.

The winning entry of the Citizens’ Hall of Tallinn Town Hall by Leila Pärtelpoeg prompted a strong response in 1973 for showing utmost respect for the building’s history while also creating a clearly contemporary solution: the oak furniture with simple construction and black chrome tanned leather details as well as the minimalist geometric form of the unique bronze lightings clearly reflected the formal language of the time. Today, this kind of an honest artist’s position has become a generally accepted approach in the renovation of architectural heritage—in case of interiors under heritage protection, historical imitation is discouraged while the existing layers are exposed primarily by subtle addition of new details.

The social changes of the 1990s were accompanied by the rapid development of new communication platforms: in addition to the club KUKU (interior architects Eero Jürgenson and Toivo Raidmets), the club culture was given a further boost by the bar Corrida designed by Maile Grünberg and restaurant Eeslitall (interior architects Toivo Raidmets and Taso Mähar).

As most people at the time still lived in the bleak reality remnant of the Soviet past, high-quality design furniture in this context acquired an artistic air capable of changing the society. The exhibition featured a culture of living that was so different that it seemed to speed up the Estonian accession to the EU even if the political factors predicted the inevitable long-windedness of the given process.

The service centre of Eesti Telefon (Pille Lausmäe) with its low counters and dim spotlights from early 1990s came across as a somewhat surreal business card for the monopolistic company but clearly predicted the diligent capitalist attitude to service provision.

The winning entry of Viimsi School (2003, architects Illimar Truverk, Eero Endjärv, Priit Pent ja Raul Järg and interior architects Kristi Lents, Hanneloore Pihlak) gave form to a learning environment that supports children’s development by focussing on their age-related differences as well as their need for spending free time in an environment contributing to their mutual communication. In addition to the flexible layout, the innovative aspects included also the need to open the building for the community after the daily lessons—this way the atrium, assembly hall and the sports centre at the back of the building become a public zone in the afternoon.

Skype head office (2006, interior architect Tarmo Piirmets) changed the local perception of a work environment—soon there was an increasing demand for informal work environments meeting the needs of the digital cloud era à la Skype that shook the functional anachronism from the 19th century and considerably blurred the work-home boundaries.

Spatial experience changes people’s habits—as certain spatial environments are perceived more modern, these become people’s preferred places for conducting their daily activities and spending free time. For the same reason people throng the current high-quality public places: Baltic Station Market, Seaplane Harbour, Estonian National Museum, Memorial to the Victims of Communism etc. When striving for carefully reasoned environments, it is worth following the lead of countries where the legislation values spatial culture, for instance, we still have a lot to learn from Finland and Denmark.

For years already, EAIA in cooperation with its supporters has drawn attention to the poor condition of the interior architecture in kindergartens—after all, spaces determine children’s development. Such activities have gradually increased the role of interior architects in designing public spaces.

At the turn of the century, the association’s position changed. Joint activities were followed by public relations and cooperation with various partners. How did they all take shape and what are your relations with neighbours and the world like in this volatile year of 2020?

Several traditions begun under the leadership of Priit Põldme and Juta Lember in 2004-2013 are still continued. We started to record the history of interior architecture with the publication of books such as ‘Pööningul’ (Leila Pärtelpoeg, 2005), ‘Tööraamat’ (Leila Pärtelpoeg, 2011) and ‘Sajand sisearhitektuuri’ (Karin Paulus 2016). In 2005, we published the first yearbook ‘Ruumipilt’ which brings together the top examples of interior architecture to this day inspiring also the publication of the current architectural award collection. In the same year, EAIA was also registered as an artistic association allowing its members to use the respective benefits in the form of creative scholarships and support measures to this day.

At the time, EAIA had professional as well as good neighbourly relations with the Department of Interior Architecture at the Estonian Academy of Arts (with EAIA office located in the same building in Suur-Kloostri Street). Having worked as the head of the department for several generations of young interior architects, Toivo Raidmets is still concerned about the fate of (interior) architecture in the society.

The application to join the European Council of Interior Architects was signed during the ECIA board meeting in Tallinn in 2012.

EAIA is a member of two umbrella organisations—the European Council of Interior Architects (ECIA) and International Federation of Interior Architects and Designers (IFI). Good relations with the umbrella organisations were rekindled in 2013-2015 when EAIA was led by Urmo Vaikla. There is now an Estonian representative in the board of either organisation (Urmo Vaikla in IFI, Tüüne-Kristin Vaikla in ECIA) so we are included in their daily activities and have a say in important matters.

Every year, EAIA participates in selecting the winners of the Lithuanian architecture awards, Lithuanians characteristically do it in a very thorough and festive manner. We have contributed to the work of Latvian colleagues mainly through professional journals.

The relations with the Nordic countries are currently curated by Reio Raudsepp (vice-chairman of EAIA). We have several common issues—the position of interior architects in the labour market, higher education and principles for public procurements. It seems that compared to the Nordic countries our position is somewhat better—separation from architecture, strong architectural basis and professional qualifications system give us an advantage in reconstructing public spaces.

What can the association do to ensure better interior architecture and more conceptualised spaces also in the future?

Although not always acknowledged, spatial culture is part of Estonian culture. The task of EAIA is to draw public attention to the fact that in a world driven by profit we must also invest in long-term processes such as spatial culture that does not immediately yield revenue. EAIA is primarily an institution driven by creative rather than business aspirations, giving voice to its members as well as non-members. The world is changing and we are ready to react to the changes. The role of the association is to act as a compass needle providing a steady reference point.

In the early years, the work was in a way easier: direct contacts worked smoothly and agreements held. Today, the members need increasingly more legal assistance, support and advice in communicating with clients and partners. Good space always requires the synchronicity of several things—a good architect, interior architect, construction company, client etc. If the interior architect thoroughly considers also the functionality of spaces, it is a form of sustainability and saving. For instance, the optimisation of space by means of parallel and cross-usage has now become a standard practice in public buildings. In terms of sustainability, it is important to make decisions on the prevention of wasting primarily on the state level, for instance, by preparing respective project briefs, and this is where we can come to assistance as a dialogue partner.

Many of the association’s activities stem from public pressure, for instance, the interior architect’s signatory authority. As a result of our recent work in elucidating the professional qualification standards, interior architecture has acquired a professional orientation and warranty. EAIA has increasingly closer contacts with its partner organisations—the Associations of Architects and Landscape Architects—as there are various topics requiring joint interventions, for instance, the style guide of Rail Baltic. We also cooperate together with local governments—all in the name of providing better spatial experience.

EAIA plays an important role in initiating discussions and creating various platforms for presenting the sector. Our longest running tradition is the above-mentioned series of annual awards featuring good spaces. Every other year we organise the international symposium SISU largely inspired by Tallinn Architecture Biennale (first TAB was organised in 2011) with the aim of offering a more fruitful platform for discussions related with our speciality. EAIA academy provides training for its members as well as other people interested in the field. The training topics are based on current needs, for instance, the changing work environment, public procurements, acoustics, special needs etc. The series of visits to public spaces ‘SISSE!’ (‘Come In!’) takes visitors to the interiors nominated for the annual awards to explore the best Estonian interior architecture together with the authors and clients. We are glad to state that landmark interiors are hunted out. It is moments like these that are allow us to define what is important for us.

As long as interior architecture receives state funding, it is considered important by the state. This, in turn, means that interior architects serve a social function carried by the association. EAIA has a duty to the local spatial culture.

EERO JÜRGENSON is a founding member of EAIA and ARS Projekt.

KRISTIINA RAID s the office manager of EAIA.

HEADER: Exhibition ‘SPACE & FORM’, 1984. Exhibition design: Maile Grünberg. Photo: Priit Põldme archive

PUBLISHED: Maja 101-102 (summer-autumn 2021) Interior Design