How can we explore the authenticity of interior space? Semele Kari moves to a barrack at Tondi and describes a pop-up interior architecture office inhabiting the desolate spaces as a methodology with the aim of finding the most suitable upgrade for them.

Notes on interpreting space

The unnoticeable yet impactful objectives of interior architecture find unique manifestations in each person in a room: the senses of an individual present in a space are addressed by its matter, eliciting different kinds of sensations and behaviours.1 A professional approach to space should not set aside sensitive matters or blur the properties of space that surface in the environment, independent of the designer.2 To assess the influence of and necessity for the designer, we must better understand the hidden aims of the space.

Unlike the daily practical tasks of an interior architect, setting goals from an artist’s perspective is for an interior designer a creative subliminal act, touching upon his or her own intuitive strings. An empirical approach as such yields the emergence of space as hyper-object. At this point, let us recall a performance by the German artist Joseph Beuys titled ‘How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare’,4 at the time of which the doors of the Schmela gallery were closed to the public and the spectators could only follow the artist in action through the windows of the gallery. Throughout the performance, the artist’s face was covered in a golden mask of honey as he was holding in his arms a dead hare who he would move around the room with, taking it from one work of art to the next, explaining to it each work. For Beuys, the purpose of the performance was to establish contact with the audience by means of their attention. The artist’s position was that humans are not capable of the same level of direct contact with the physical world as hares and bees, but that humans have the ability to think which is what the gold with honey was implying. Beuys considered the ability to think, analyse and interpret the greatest strength of mankind.5

The aims of the performance provide a base for a comparison to interior architecture and how active engagement may be the means to amplify hidden spatial values. While spatial awareness has rapidly expanded over the years, as creators of space I tend to think we have rather neglected the purposefulness of our innovative practice. We need to recreate the hyper-object that would enliven in us a boldness to feel doubt and be mistaken.

In a sense, every spatial dimension is grounds for a hyper-reality, but in Joseph Beuys’ performance I am referring to the spirited joy of discovery within the communication between the author, the audience, and the work (read: the space). In this case, the space does not prescribe answers but encourages one to wander and create one’s own spatial relations. The willingness to embark on such a journey is, however, dependent on the previous contribution of the creator.

Working with the detritus6 of past interior architecture, it is my goal to create unpredictable borderline space that would unwrap itself over time. The space being created then does not provide answers but instead rouses us to explore and ask questions. For the person inside the interior, both the pragmatic and the aesthetic spatial needs are put to the test, rendering individual perceptual experience as the reference point.

The interior architect is consciously creating a space for use but experiencing and internalising the space may remain on the borderline between the conscious and unconscious awareness. Space does not only create environment but does something more7—space addresses and guides the subject, creating a platform for perpetual discussion. It is possible to assign space a designated role in relation to the person in it—the space as protector, the space as partner, the space as healer, etc.—that means that the space actualises in conjunction with, and for, the person in it.8 The interior is not just an expression or exertion of the designer of the space, but rather a joint language of all the participants in the space where sensorial means of communication merge into one.

Pop-up as architectural mining/planning

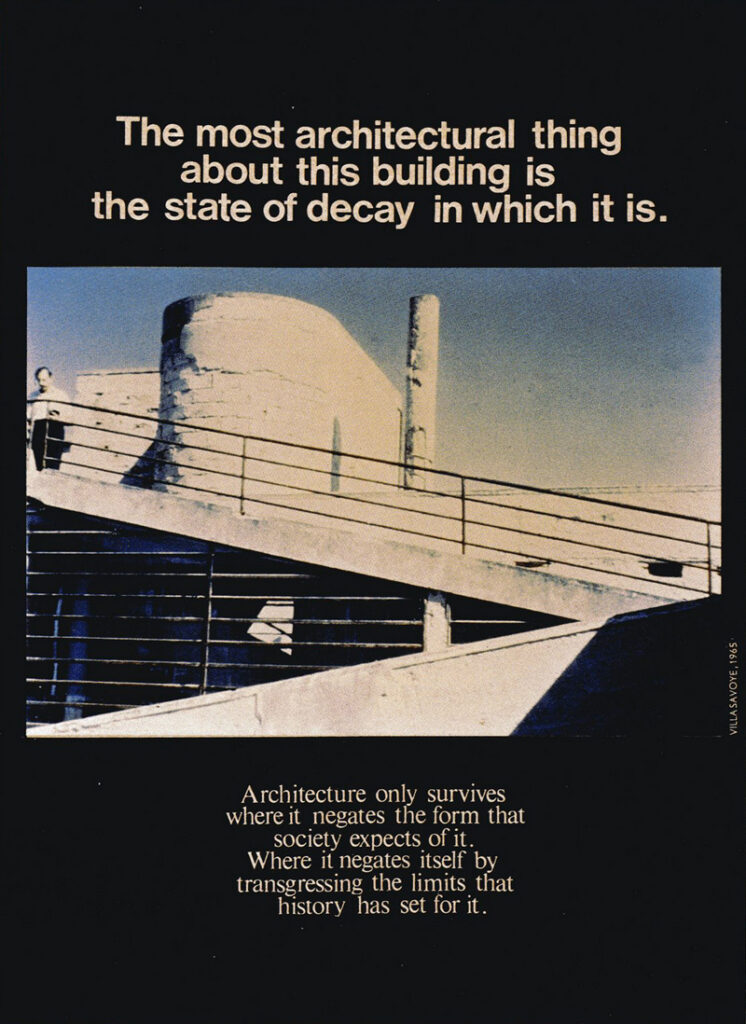

When designing space in a building whose architecture largely originates in the past, it is the ethical responsibility of the interior architect to pass on a quality that cannot be artificially reproduced. It is important to notice the possibility and make it visible to others as well.

Values inherently present in an old building impact strongly on the subconscious while often remaining inconspicuous for the person in the room. The term ‘restorative’ is used in environmental psychology which refers to a psychological or physiological restorative process that is contingent upon a certain environment and its qualities.9 An abandoned interior fits the criteria that I wish to emphasise as a spatial designer: an aesthetic experience, distance, wide openness, coherence, and compatibility between the needs of the person and the properties of the room.10 Irregularity and imperfection characterise the view that has the potential to attain these criteria.11 Space that is not finished to a fault, feels cosy and allows the person to feel comfortable inside it.

The drift-engagement strategy is about temporarily and seasonally repurposing desolate buildings, while offering alternative work environments for (interior) architects. Each project is a new location to be viewed and examined. The primary objective of intermediate use is to create better contact between the abandoned space and to learn about its potential for reuse. My concept proposal is about moving into the existing building, collaborating within its conditions, and introducing the current state it is in to the public—the purpose of which is to find a suitable solution for the building. The primary aim of this type of intervention would be to establish more effective construction activity and better-quality results, with architectural heritage in mind. Renovating a building should mean added value but not on account of existing value.12

The other aim of the concept of being driftingly engaged in intermediate use is to break the barriers that keep us confined in everyday life. By travelling to unforeseen places, we subject ourselves to unforeseen sensations. We become mentally engaged with a space when we can intervene in it, by discovering or changing something in it.13

In a collective unit, we can achieve this through shared spatial design. Spatial design is a democratic intervention at the core of which we find active inclusion of interested parties.14 Anthropologists are drawn to spatial design for the practices it entails that reveal how an anonymous space might become a significant one for an individual or a group of people. Proper orientation in the strategies of spatial design is a useful skill for a spatial designer who wants the new space to be used as a positively charged one.15 An important part of the action plan of intermediate use is communication with the community by means of spatial interviews—visual interviews carried out during my fieldwork provided important input for further informing the space. Contact with the visual aesthetics of an abandoned environment in my experiments has proven that the public is receptive to and positively attuned to such spaces. I noticed my role as interior architect, as cognisant of the space, played a critical role. A spatial designer must practice and actualise her intuitive sense. Temporary solutions are in fact research methods for a better understanding of space.

Cultural memory is always tied to the current needs of the collective, which is why it is more profitable to not consider it as a possession, but rather as a process.16 Spatial design as collective activity is one of the most effective means to release daily tension.17 Contributing in an unknown atmosphere by way of personal intervention allows an individual to open up. Personal and public space intermingle; what was once a blocked connection between different people has become unblocked and the space is accommodating of comfortable and public behaviours at the same time.18 Due to organic communication, space expands for open disagreements, for understanding, for caring. Space that brings together while also enabling seclusion.19

***

Endnote

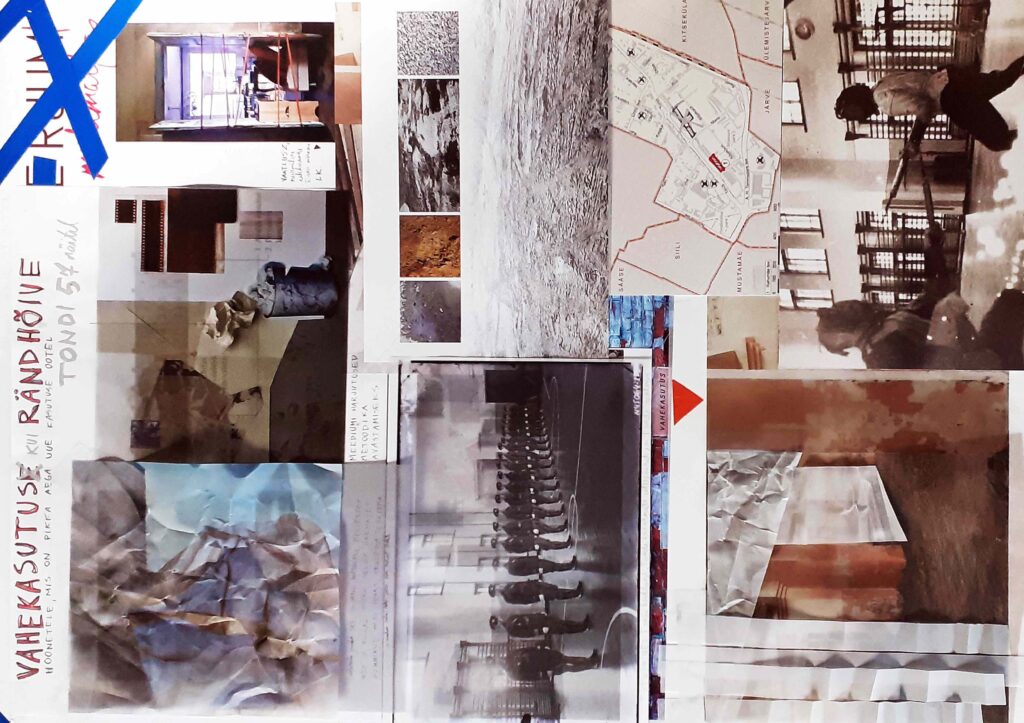

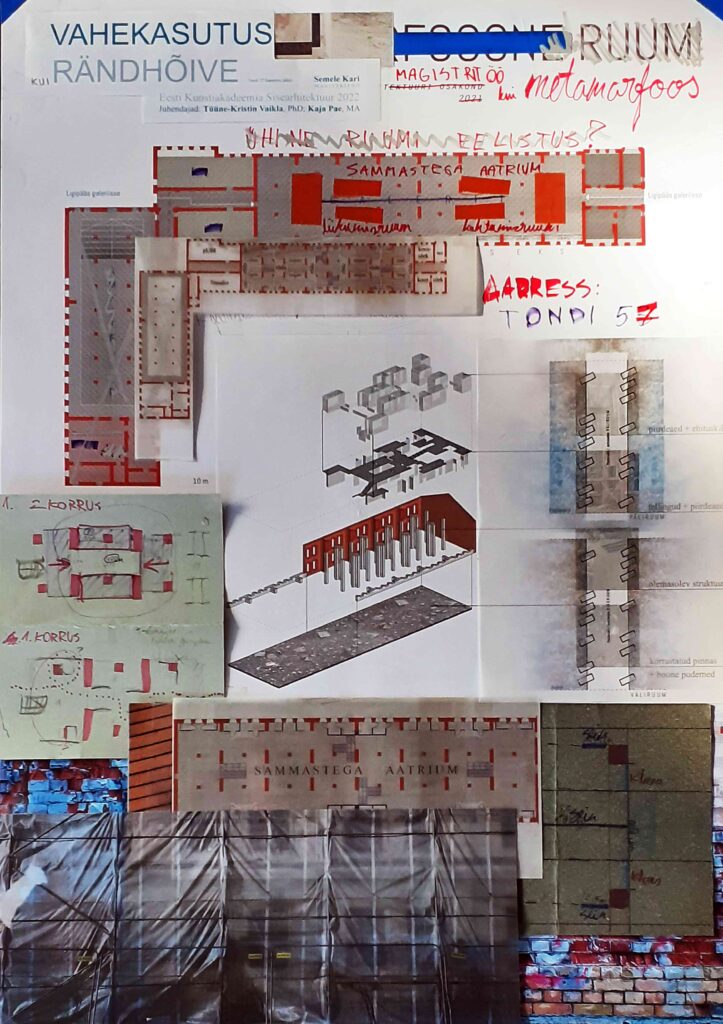

Rearranging posters as collage and assemblages evolved into a medium in its own right as the project advanced. I started adding layers on top of one another in the process of the theoretical and visual work. This type of method is contextually more in tune with the content of my research. Reinvigorating an existing space can be further valorised by purposefully using existing materials in the building. The same applies to my posters. The resulting visualisation must be a stratification of previous ideas and visions.

The text is based on the recipient of the Tallinn Town Hall award Master’s thesis ‘Driftingly Engaged in Intermediate Use’ defended at the Department of Interior Architecture of the EAA in 2022, supervised by Tüüne-Kristin Vaikla and Kaja Pae.

During the years in interior architecture, SEMELE KARI has learned to notice details and appreciate irreplaceable values in our cultural heritage. Planning her ideas in various media provides the freedom to express her fantasy that can later be eloquently transposed into spatial design.

PUBLISHED: Maja 109-110 (summer-autumn 2022) with main topic Built Heritage and Modern Times

1 Christele Harrouk, „Psychology of Space: How Interiors Impact our Behaviour?“, Archdaily, 20.03.2020.

2 Bernard Tschumi, „Space, Event, Movement“, Pigeon Digital (kõne, 14.11.2014 ), https://dezignark.com/blog/bernard-tschumi-concept-notation-november-10-2014/.

3 A hyper-object is a complex perceptual multidimensional object. The term has been addressed by Timothy Morton in the book Hyperobjects where the concept is used to denote things which ‘from the human perspective are massively dispersed over space and time’.

4 Balasz Takac, „Joseph Beuys and How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare“, Widewalls, 28.01.2020.

5 David Craven, „Conceptual art“, Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online (2003).

6 In Eesti keelt seletav sõnaraamat, ‘detritus’ refers to something miniscule and insignificant. The word has been used to describe debris found in nature such as leaves, branches, also lamb wool. That is why the word is suitable to describe the unapparent value of my object, because similar to nature, the life cycle of the seemingly meaningless scrap of artificial environments is a value in its own right.

7 Juhani Pallasmaa, „Keha, mõistus ja arhitektuur,“ SISU-LINE 2 (2015): 23.

8 Suzie Attiwill, „Nägemus+haridus,“ Maja 101-102 (summer-autumn 2020): 176–177.

9 Silver Sternfeldt, Aksel Part, Marju Randmer-Nellis, Julia Trunova, „Keskonnapsühholoogia sisearhitektuuris,“ Maja 101-102, (suvi/sügis 2020).

10 Ratcel Kaplan, Stephen Kaplan, The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989).

11 Grete Arro, „Suured pisiasjad linnaruumis“, Arhitektuurimuuseumi loengusari: Elav ruum (märts 2021).

12 Laura Elisabetta Malighetti, „Four renovation strategies for reconsidering buildings,“ Materia 71 (2011): p. 152.

13 Kadri Kallaste, „Sisekaemuslik rada – Kolga mõisa vahekasutus“ (Master’s thesis, Interior Architecture Department of EAA, 2020), pp. 27–29.

14 Madli-Johanna Maidla, „Kohaloomest kohahoidmiseni? Kuidas kodanikke püsivamalt avaliku ruumi korrashoidu kaasata?“, EU: UrbAct, veebr 2018.

15 Sigrid Solnik, „Argikultuur ja linnaplaneerimine“, Sirp, 22.01.2021.

16 Linda Kaljundi, Helen Sooväli-Sepping, Maastik ja mälu. Pärandiloome arengujooni Eestis (Tallinn: TLÜ Kirjastus, 2014), p. 20.

17 Madli-Johanna Maidla, „Kohaloomest kohahoidmiseni? Kuidas kodanikke püsivamalt avaliku ruumi korrashoidu kaasata?,“ EU: UrbAct, veebr 2018.

18 Ronald Reema, „Kes tegi?“, Maja 98 (sügis 2019): p. 20.

19 Juhani Pallasmaa, „Keha, mõistus ja arhitektuur“, SISU-LINE 2 (2015): p. 14.