Big questions

How to plan and design the city and public space in a situation where every owner of even a tiniest land parcel has its own interests and every public authority or private company has its own needs? How can it be done if every city department has its own concept of urban planning, if architecture and engineering firms expend all their efforts simply keeping their head above water?

Many of us are critical of status quo, yet the wider populace in fact has no idea what they could and should wish for or desire. In such a situation, instead of pondering, “how do we envision the best urban space and how can we create it?” one only thinks, “how can we get this project done and off our backs as quickly and painlessly as possible?”

Design of any new building is subject to either design specifications or a detailed spatial plan, requiring a prior public discussion to be held at least with the immediate neighbours who usually show keen interest in the process. In contrast, public space, including roads and streets, is designed without exceptions by way of public procurement where contracts are awarded to the lowest bidder, a process which no outsider can contest or influence. The resulting urban space is mostly skewed towards favouring car owners, it complies with established requirements and is more or less safe, but often lacks in smart design both from the perspective of pedestrians and car owners.

How then are you supposed to behave if you feel that things are wrong, if you know that something should change and you desire to do something better? If the objective can be perceived, yet the path leading to it is a completely untrodden one?

Following the example of startups

The concept of a ‘lean startup’ is used in the world of fledgling businesses. It constitutes a methodology whereby a new product or service is brought to the market as quickly as possible, to be subsequently improved on the basis of clients’ feedback and released again to the market as an upgraded version, so its development continues in a cycle of feedback and new releases. The initial product astonishingly often nearly completely fails to meet the needs of the market and a failure looks certain. In this situation, however, a U-turn is in order, the old vision is discarded and a completely new one is quickly created on the basis of the lessons learnt. This time, however, the probability of a subsequent failure is much smaller, since now with the clients’ feedback from the previous time, their concept is based on the opinion of a much wider circle of people.

A learning city

As with a starting business, the Tallinn Main Street project involved numerous trials, new lessons and successes, but also miscommunication, fruitless negotiations and failures. We submitted our proposed concept to scrutiny by the public and the companies, we presented and discussed various solutions at different events, we visited people and people visited us, we interviewed specialists, companies, land owners, community members, as well as foreign experts, and invited them to participate in the city forums. A notable guest speaker at the first city forum was Ewa Westermark, Director of Gehl Architects, who gave a lecture on public space strategies. Her team proposed the idea of using temporary activity sites and solutions in new developing urban space for the purpose of its speedier integration in the city’s fabric. Making changes is always difficult and it easily runs into opposition, but through the creation of temporary destinations and leisure sites, it would be possible to “naturalise” the urban space, accustoming the city’s denizens to its new interpretation (read: places of walking, sitting, swimming, etc.), at the same time also receiving relevant feedback from the actual users of the space. It is a learning process, since after the preliminary realisation of the ideas, using relatively cheap materials and equipment, and only a few months of testing, the people’s opinion can be asked, on the basis of which it will be possible to decide whether these temporary solutions should be given a shape more permanent and with better quality, or it is better to return to earlier versions.

Drawing inspiration from these suggestions, we attempted to launch the Main Street Sprouts project which, quite frankly, was largely a misfire. The amount of resources required to get such a project off the ground and keep it going was too significant and our lobbying efforts with city departments were not successful enough either. Yet we tried. The visible vestiges of this part of the project in the city include the bicycle stand under the fire escape of Tallinn Creative Hub (Kultuurikatel), the installation art on the Hobujaama Square and the new Hobujaama Street—Narva Road traffic solution created for the Estonian Song and Dance Festival. I do hope that some of the ideas suggested at the time will materialise as additional experimentations before the full realisation of the Main Street.

I have already participated in about ten city forums and have also helped to prepare them, and it seems that their underlying theme is always the same: urban space that is well-ordered and functional, pleasant, with a human scale, visually thought through and well-balanced between road users. These priorities may appear boringly similar, but actually, during the last fifteen years a quiet but constant development has taken place, taking in the knowledge and ideas of wider interest groups, and I think that we could be on the brink of a paradigm shift.

Model urban space

The core objective of Tallinn Main Street is to be a local Estonian model example that would define the springboard towards new urban space. A similar springboard as for us, when we formulated the core principles of the Main Street project, was the design of Soo Street, proving that urban space can be developed in a balanced manner, without forgetting the pedestrians and cyclists.

Main Street project

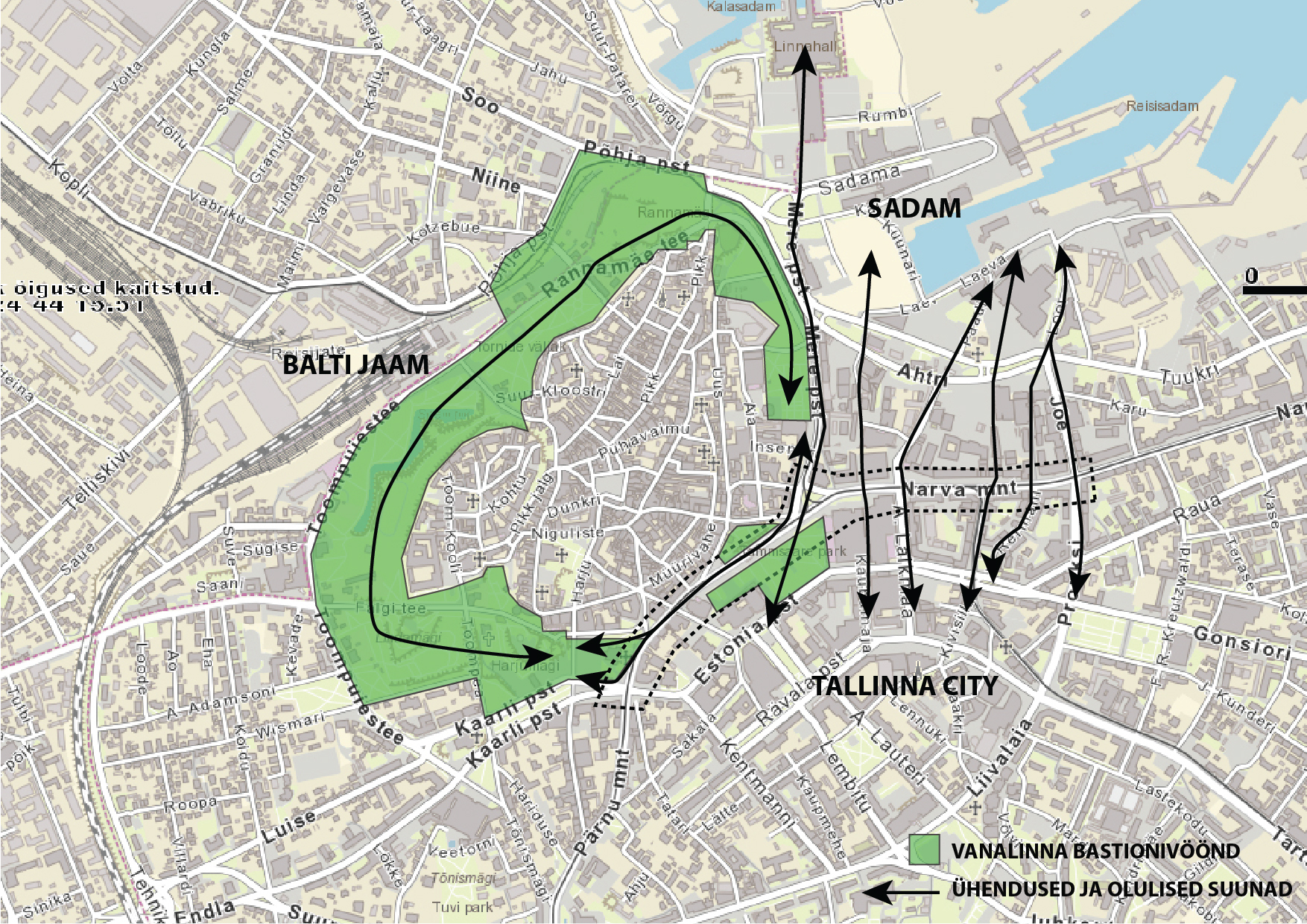

From spring 2016 to spring 2017, the Estonian Centre of Architecture worked on a Main Street project that in truth was but a preparatory phase. The project consisted of two stages—the central Tallinn parts of Narva Road and Pärnu Road, forming the Main Street—and connecting it with the developing urban area at the seafront. The development of the solutions for both stages is outlined in the scheme below.

In preparation for the project, a substantial number of surveys were conducted, thorough and detailed descriptions of the desired environment were prepared and city forums were set up for the scrutiny of new ideas. The surveys were conducted by specialists from professional circles and research institutions. After the city forums, the general competition terms and conditions were created for two architectural competitions, the first of which, the Tallinn Main Street architectural competition, was included among the series of competitions to be held in celebration of the coming 100th anniversary of the Republic of Estonia. The competition terms and conditions were rather detailed and even specified recommendations for traffic solutions.

Main Street team

A fluctuating group of people with different backgrounds and education, knowing each other for different reasons and from different places, in frequent communication with each other and mostly getting along well—such was the core team of the Main Street project. The Main Street team consisted of the mobility expert Marek Rannala, architect Jaak-Adam Looveer from Tallinn Urban Planning Department, Liis Vahter from the Transport Development and Investments Department of the Ministry of Economic and Communications, city architect Endrik Mänd, architect Aet Ader, media expert Lauri Linnamäe, Head of the Estonian Architecture Centre Raul Järg, architect Renee Puusepp and project coordinators Angela Kase and Tiit Sild.

Winning trust

The Main Street project, since its goal was to achieve something unprecedented in the context of Tallinn and Estonia, was definitely a challenge. First of all, although none of us is satisfied with the existing urban space, our outlook to the future is optimistic. The questions which motivated us were simple but important. What are our goals? In which direction and how should we move? It was clear from the beginning that no-one takes us very seriously and the project’s financial backers had doubts as to the ability of our team. Yet, against expectations, we did not disappear, one meeting followed another, larger gatherings took turns with personal encounters, we asked questions and conducted surveys. Our efforts increased our confidence, plans began taking shape, city forums and architecture competitions started being held.

Great communication entanglement

It is required by law that the interested parties must be invited to participate in planning processes. From my days as the city architect of Tartu, I remember that the detailed spatial plans rarely failed to draw out the concerned landowners, whereas the public discussions of comprehensive plans were rather quiet affairs. Larger scale, more abstract talk and less personal interest. How to be more successful in engaging and involving people? A half serious answer is simple: by setting up a city forum! However, it is clear that, in order to reach people, much more effort should be put into communication across many different channels. You must go to your target audience yourself and not wait for people to show up at the meetings. Personal approach is also essential. It should also not be forgotten that beyond involvement, one also faces the question how public opinion can be integrated with professional knowledge. Involving interested parties is important not only for the purpose of exchanging information. It is also crucial that all parties feel assured that they are being heard, that their opinion is valued or, in fact, that they are approached at all. As in a party crowd, modest fellows are invisible, loud talkers are heard, and the really loudest bigmouths are silenced, it is no different in urban planning.

One of the most complicated tasks within the Main Street project was indeed the management of communication. The acquisition of input information from the companies and city’s denizens occurred in parallel with presenting and gathering feedback on the team’s proposals. Several strategy documents were prepared, including a communication strategy and an engagement and involvement strategy. For engagement and involvement, we used several tools and relied on experts’ knowledge. User feedback was obtained using the virtual Sticky world platform and conducting surveys among the city’s denizens in the urban space. For feedback from local institutions and companies, we prepared two thorough questionnaires, with larger companies, we also conducted in-depth interviews. All this took place under the careful oversight of social scientists. Companies were the easiest, they have usually analysed the problems from their perspective and often already have the answers. The larger organisations were trickier, and the communication with the city administration probably took the most complicated and multifaceted form. Our goal was to create the largest area of agreement possible between the city departments, and I am still not entirely convinced that we quite managed to do that. Time will tell.

The project came to a close, the Main Street projects were turned over to the city, yet a lingering feeling of something not quite finished remains… It seems that everyone involved, including myself, has still a lot to learn how to tie up the loose ends of a project. Although the Main Street project has been quite frequently mentioned by politicians, generally in positive light, it seems to me that the connection between politicians and urban space experts remains weak, perhaps more lobbying is needed. Yet, at least partial funding exists for the realisation of the project and I do hope that our determined and persistent work on the project has left its mark and will eventually lead us to our goal.

The Tallinn Main Street project was launched by the Estonian Centre of Architecture, Tallinn City Administration, Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communications and the Environmental Investment Centre. The project participants included the Union of Estonian Architects and a number of private and public developers and experts.

TIIT SILD has worked as Tartu city architect and is currently leading platform katus.eu, which aim is to develop and provide high quality pre-designed houses.

HEADER image by Maa-amet

PUBLISHED: Maja 91 (autumn 2017) with main topic Shared Space