Interview

It seems that in architecture, the only way to ensure high quality is to rely on commitment, consideration and precision. Tomomi Hayashi and Hanno Grossschmidt do their work in a composed manner with professionalism and commitment. And their architecture speaks for them.

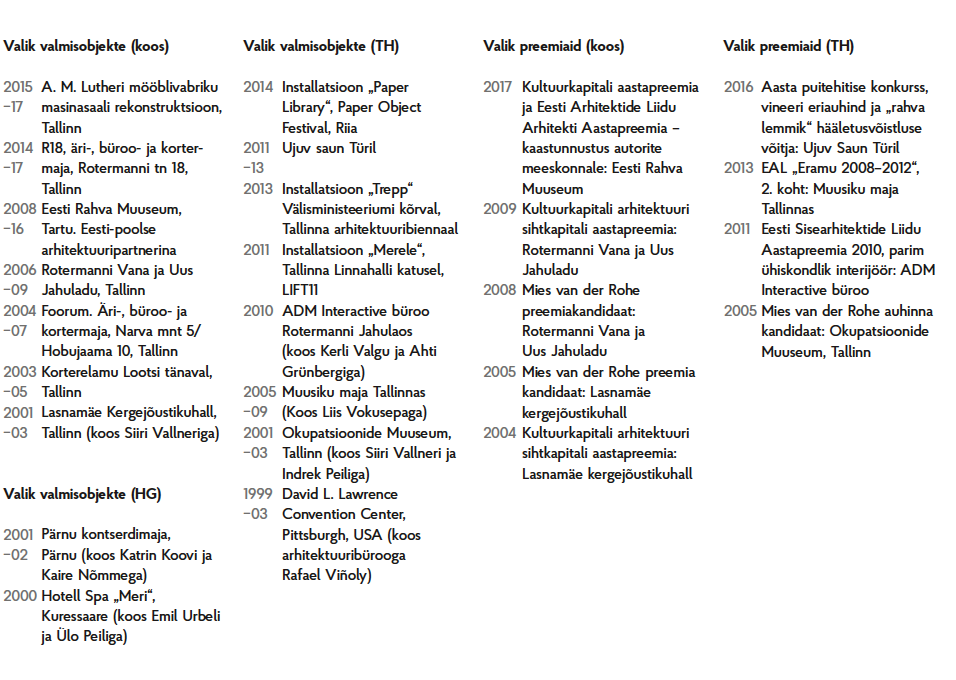

TOMOMI HAYASHI (1971) studied architecture at Yokohama National University in Japan and Virginia Tech in USA. After graduation, he worked briefly for Maki and Associates in Tokyo and Rafael Viñoly Architects in New York. In cooperation with Siiri Vallner and Indrek Peil, he established the architecture office Head Arhitektid in 2001. In 2003, he worked with architecture office Kosmos and in the following year joined Coo Arhitektid that later grew into HGA (Hayashi Grossschmidt Arhitektuur). Since 2012 he has worked at the Architecture Institute of Tallinn University of Applied Sciences, since 2016 as an associate professor.

HANNO GROSSSCHMIDT (1973) studied at Tallinn University of Technology, Estonian Academy of Arts and the Washington-Alexandria Architecture Consortium of Virginia Tech in USA. He has worked for AS Entec, Urbel and Peil Architecture as well as McAllister Architectural Consulting Services in Alexandria, USA. Together with Kalle Komissarov, Katrin Koov, Kaire Nõmm, Rene Valner, he established COO Arhitektid in 1999 leading to the establishment of HGA (Hayashi Grossschmidt Arhitektuur) in 2004. He was awarded the Young Architect Prize in 2010.

Kalle Komissarov: What makes you come to work in the morning? What drives you? I, for instance, still believe that I can make the world a better place.

Hanno Grossschmidt: I suppose we all want to do everything as effectively as possible and if it delights or benefits someone, then the world is better. This is my job and I have to do it well.

Tomomi Hayashi: In my case the driving force is self-fulfilment, but I would also like to improve the surroundings and the environment where I live.

KK: What is the starting point for your designs? Do you need theories?

HG: As long as it helps, yes. Theory is one fragment of the more extensive frame of reference that you sometimes need, but not always and not necessarily.

The client’s brief is of primary importance – who needs the building and what for. It is also important to consider the public interest, as the neighbours as well as the general public should have the opportunity to express their opinion during the design process.

Similarly, the location is highly important. And if it happens to be a boring place, you can turn it into something challenging and intriguing.

TH: We find inspiration in the location, but design is a complex process. For instance, last year a new law came into force in Lithuania listing all the quality requirements that need to be met in high-quality architecture. There are 10 points giving you an overview of the diversity of architecture: integrity in terms of urban design, sustainability, high-quality construction, innovation, cultural heritage, universal design, the comprehensiveness of the architectural idea, functionality, aesthetics, and rationality.

The Concept

KK: An architect cannot just wander around discovering the world, at one stage you feel you have some experience and preferences. Does HGA have its own DNA?

HG: I believe we are quite flexible. The customer assumes that the architect has his own position regarding more general issues as well as specific questions. He then either agrees or disagrees with them, it doesn’t really matter. However, the architect should be able to give advice and engage in a discussion.

KK: When I studied, the concept was everything. Both in architecture and in visual arts. If you have no concept, you have nothing!

HG: Concepts are naturally very exciting, but they tend to speak only for our profession. As a rule, the users who the architecture is designed for have no clue of the given concept, they are more concerned with the practical and aesthetic aspects. If architects are only interested in concepts, it will result in detachment and isolation.

KK: Sometimes the concept is aimed at improved communication. A well-known example is the contemporary school of Danish architects who are very good at international marketing. It is said that they spend a week for thinking and a month for the visualisation. They emphasise their concept that is in the form of a simplified and even rather banal diagram. It has nothing to do with space.

HG: This is clearly an issue of sales – and isn’t that perhaps one of the most important parts of the work of an architect – how to give form and package to your ideas.

TH: Hanno said that the concept has no sales appeal to people outside the architectural profession. But we need the concept for ourselves: why we do things, why it is an interesting project for us. You need a concept to drive you. And it sometimes happens that the concept becomes clear only at the end of the project. And the concept could open up new perspectives for the clients.

The Author

KK: We’ve spoken about architecture in general, but let’s talk about the architect too.

Another topic that we should discuss in greater detail in the society as well as in the field of architecture is that of an author. The issue of copyright, its protection and authorship. What is your relationship with authorship, what is the role of the architect?

Here, our two giants Raine Karp and Toomas Rein would serve as good examples. At one point, Raine Karp declared that his active career was over, but he understood that life went on and he would not oppose if somebody wanted to adapt his buildings to the new requirements. Toomas Rein, on the other hand, says that each architectural object is a comprehensive work of art, he is the author and if he doesn’t change it, nobody else will either.

HG: My sympathies are with Raine Karp. I would simply conflict with myself if I started to pursue copyrights. Works of art include drawings and images, this is what the author does. The author does not construct the building with his own hands. We can’t say that it is his – there have been other people involved in drawing it, designing the structure, pipes etc. The title block of our drawings includes all the people participating in the design, so it is joint authorship.

KK: But what if some of your buildings needed reconstruction?

HG: So far, the client has first turned to us. It is natural, nice and understandable, but we can’t blame the client for saying that our architecture no longer suits them.

But if I had to redo some of my old projects, then in case of Jahuladu, for instance, it would be highly difficult. It would be no problem in case of a building that came out poor.

KK: Do you see your office as a studio or atelier? The latter has a clear hierarchal form.

TH: I would say a studio but each project has a leader who is responsible for seeing it through. In that case the process management is no longer so horizontal. That is only natural.

At present, there is ten of us and there was also ten of us during the previous boom years. This way we can still keep our finger on the pulse and keep track of the ongoing projects.

Boom!

KK: Architects are doing well at the moment, is the Estonian architecture also doing well?

HG: The whole country is doing well – economy is strong and if customers have money, they can also invest more in architecture.

KK: Are you saying that architecture is a luxury and you cannot do architecture when times are bad?

HG: Of course you can, but there are fewer possibilities. Some typologies disappear and resources are scarcer.

TH: Much of Potsdammer Platz in Berlin was designed and constructed at once. The entire environment there exudes the feel of 1990s, there is no rich diversity, for instance there are no old or new buildings. So it lacks variety and different scales.

HG: Both extreme ends are dangerous, the best option is tranquil development.

KK: Having designed the largest building in Estonia – the Estonian National Museum, do you have any other dreams? Something in the superlative degree department?

HG: The Estonian National Museum is not the largest building by far, not even in Tartu. In terms of square meters, even the shopping centre Kvartal is bigger. And in terms of length, Tallinn City Hall precedes it – 500 metres from staircase to staircase. The museum is actually a small compact building. Even in terms of construction costs, it is not the largest! Everybody is stunned – oh, how expensive, oh, how large! But to compare, in the same year that the museum’s construction procurement was held, the national airline Estonian Air was declared bankrupt. And the loss made by this state-owned company in one year was 81 million euros! Now consider the Estonian National Museum with its building taking 100 years to prepare and complete: the mere construction costs amounted to 40 million euros and the total costs including the interior furnishings to 70 million euros!

TH: The Estonian National Museum is often taken as a unit of measurement, however, it’s important to remember that its end-customer is the Estonian nation. I feel truly happy to have been a part of that process.

KK: What else would you like to do, what kind of typology would you like to try?

TH: Designing on various scales is very healthy. I feel tired after completing a large project and I would like to do something smaller. Installations, for instance. With them you get instant feedback.

Competitions

HG: At present we are in the middle of several invited competitions that usually have 4-5 participants. There are no architects in the jury of such competitions – that is the harsh reality of competitions organised by developers. If there are no architects in the jury, the results are unpredictable – then again, architects themselves do not really buy anything in such developments either or pay for their solutions. So in this sense, it’s fair business.

KK: In the Estonian Association of Architects, we are trying to bring some order in the architecture competition culture and provide all participants with equal opportunities. But in case of private competitions, our hands are tied. How would you explain the fairness of a competition where the participants are paid for their entry and there are architects in the jury?

HG: There are also examples of the reverse with architects in the jury but the competition still failed! Let’s say that there are ten criteria to ensure a good building, but among these only perhaps two or three are close to the architects’ heart. It is hoped that the remaining ones would also somehow be solved, but tough luck!

KK: When speaking with architecture competition jury members, they have said that the main focus has now shifted to the visualisation of the entry. And the assessment is naturally largely based on the image – with all the attractive images, it later takes some explaining that the design is actually quite poor.

TH: The visualisation is certainly important, but the jury must also see behind the picture.

HG: And they need to consider how it is possible to construct it, how it suits the users, and how it will function also in 10-20 years. I’m not saying that images are not important. Some of our good projects have not succeeded because there was not enough time for the packaging. It is particularly evident in competitions where the winning entry has poorer content but a better packaging.

BIM

KK: The tools that the architect uses also have an effect on the final result. When the work of an architect was largely manual, buildings were different from those created after the invention of computers. Do you think that digital architecture will solve all the problems in the world?

HG: We have used BIM for our projects already for 12 years. It’s not a magic wand but a regular tool. Formerly, people used to have BIM inside their head and they managed just fine. It can happen also in today’s modelling that people claim to work in BIM but the pipes are still a mess.

TH: At school I see that when students work in 3D modelling, they no longer think of sections and the section becomes the result of the modelling instead of a reasoned and constructed idea. Earlier they drew the plan and the section, combining them in their head. Modelling makes you lazy as you leave out one stage of checks.

KK: Older architects have commented on that by saying that the plan shows the spatial system while the section shows the emotion of the space. If you don’t think about the section, you will not achieve any emotional quality with the space.

Tomo, as you work at the university, can you make use of your academic experience in your daily practice?

TH: Working at school trains the eye and it helps you to find mistakes or potentials in the projects faster. At school, you can also work with several solutions at a time, allowing you to select the best one.

Information

KK: Do you keep track of what is going on in the field? Do you read blogs or do you prefer printed media?

HG: There’s no time to follow blogs, we are overflown with information. At one point we subscribed to the German magazine Detail. It featured the high quality and elaboration of technical solutions – how well it is all done and you aim at reaching the same level. The magazine is a collection of the best professional examples featuring their current level.

TH: Magazines have editors who put together a comprehensive whole under their own name. Blogs are like taps that simply flood you.

In the fall semester, I will assist in supervising the first-year interior design students at the Estonian Academy of Arts. In the preparation one of the students said that previously after getting a task they rushed to browse magazines. But now there is so much information that students first need to clear the information – to look for inspiration within themselves, their surroundings, experience or past. When studying in Yokohama, I also felt that there’s too much information in Tokyo.

Material

KK: Let’s talk about materials too, as you go to the smallest details in your projects and deal with technical design to the joint level – in other words, you think in terms of material. I think it is admirable and commendable. I’m sure that the next goal in improving the quality of Estonian architecture should be better knowledge of building materials and designing on the level of details. Fancy images have exhausted themselves with no contribution to building quality.

Have you developed some signature materials over time?

TH: No, I haven’t found my signature material yet. We use wood, concrete, steel etc. We haven’t used only one building material throughout an entire project, but we know which aspects of the material would lead us to an interesting result. In the Estonian National Museum, for instance, the use of reinforced concrete was included already in the initial concept. Similarly, concrete has an advantage in Estonia compared to steel, as it is simply less expensive. But getting a beautiful authentic concrete surface is extremely difficult, as the human factor cannot be fully excluded when building by hand.

KK: As an observer, I can say that there are architects whose works can be immediately recognised by their use of material. Material plays an important role in your projects and your works can also be determined by it.

HG: Ten years ago I personally felt that the entire local mainstream architecture was cold and cool with stylish grey tones and metal surfaces in a palette of cold tones. But we found the given approach highly monotonous and that’s why we have attempted to design buildings in warmer hues. We feel free to use brown and green tones!

KK: As life in Estonia has considerably improved in the past ten years, also architects have more room to experiment with material.

HG: Estonia is still a small provincial country. Clients travel around the world and see buildings made of exclusive materials, that is when the question arises if they dare to make such an investment here. Or if there is no point in spending on high-quality materials as it will never pay off here. Usually, the developer states the price per façade square metre and it turns out that it isn’t even enough to cover the entire building.

The rationality of the plan is highly important. If you can make it so rational that there is some reserve in the Excel table, you can spend it on better building materials. For instance, in case of the apartment building in Lootsi Street, the façade cladding material was 2-3 times more expensive than its analogues. However, the ratio between the saleable and constructed gross area was 90% instead of the usual 75% and so we could use better materials in the façade.

Thinking back to the completed projects, we have been bold in selecting cladding materials.

The façade of Jahuladu uses cor-ten steel that hasn’t been used to such extent in Estonia. During the construction, we even tested with a mock-up façade panel to check the visual impression and the reliability of fastenings.

Prior to the building in Lootsi Street, there had been no apartment buildings with glass or plywood facades of such scale in Estonia. It is actually natural wood veneer that is laminated and thus very sturdy.

The building at 18 Rotermanni along Ahtri Street is clad with aluminium composite panels. The round corners were used to open more views towards the quarter and the dark tones to provide a background to the historic facades. There’s a small square behind the building that gets no direct sunlight. To bring more light to the street, the reflective balcony surfaces are placed at an angle. The reflections were modelled earlier and also tested in the lighting technology lab at Tallinn University of Technology. So, the place is worth visiting at midday.

TH: As everything reflects, the building itself remains invisible!

HG: In the interior of Luther’s Machine Hall, an important role is played by plywood. As the façade required the restoration of limestone and plaster, we added a lot of plywood surfaces in the interior. Interiors generally tend to use light Nordic birch plywood, but we wished to achieve the tone of a hundred-year-old plywood. We deduced the caramel tone from the varnish coating from that time, reminiscent of the furniture manufactured back then by Luther factory. The Machine Hall interior was designed by our office, some details were done also by interior architect Kadri Tamme.

The aim with Luther’s Machine Hall was to reach Class B energy efficiency, however, the building is old, the interior spaces high, with glass ceiling and massive stone walls. We went to Tallinn University of Technology to ask about the options for the limestone walls. They couldn’t make any recommendations, which is kind of ridiculous, as the entire Old Town is full of houses with limestone walls, and actually until the czarist period, they built houses with massive stone walls. Today, the calculations consider it as a cold wall, but in practice we know that such a wall can function very well as an exterior enclosure. We have similar walls in our office. Heating costs of flats and offices in such buildings are perfectly reasonable. Limestone walls can actually be good – stone is inert accumulating warmth in the summer and thus postponing the heating period. Air humidity is right. The engineers at the university suggested that they measure the given wall. We should have built an isolated cube of 3×3 metres within and outside Machine Hall wall to create a field laboratory for taking measurements all year round. The question itself was actually simple: does humidity move in or out? So eventually we did nothing with the walls and it was still given energy efficiency Class B according to the project. As the building is large and wide, the wall areas were not very numerous and had no effect on the calculations.

In all the projects that we have talked about today, we have deliberately selected uncommon colours for window frames and the metal parts: they are often either pearly-gold, pearly-beige, brass or blackish-brown in hue. In Estonia, architects blindly go for anthracite in all their objects – in this sense, we are more prone to experimentation!

KK: Tomo, did they teach architecture through materials or concepts in the schools that you attended?

TH: When I studied, Yokohama school was very theoretical and concept-oriented. Buildings were mostly white and the main building material was reinforced concrete with a thickness of 20 centimetres. They only stressed the aspects related with urban design, not the spatial experience or poetics.

At Virginia Tech, they taught materials and talked about tectonics. I would highlight professor Marco Frascari. There were very good workshops where you could experiment with materials yourself. And tectonics is a topic that attracted me then and attracts me to this day.

KK: I feel that in terms of conceptual level, we have world-class architecture in Estonia. However, when we compare ourselves with neighbouring countries Sweden or Denmark, then in terms of the quality of the built architecture we are lagging behind. There is room for improvement in materials, details and quality. We cannot take that leap in education, so we must invest in practice.

HG: But it isn’t entirely up to the architect to decide, as high quality and details actually cost quite a lot. The question is whether the building is mass production or a custom-made unique object. And if the client has the necessary awareness as well as interest, you can also ask for quality.

TH: If general public thinks that a plastered house is a sure thing, there will be buildings with no details everywhere. White plaster!

KALLE KOMISSAROV is a freelance architect. He has been a member of the Estonian Association of Architects since 2007 and a member of its board since 2016.

PUBLISHED in Maja’s 2018 summer/autumn edition (No 94).

HEADER photo by Renee Altrov.