Toomas Paaver admits that solving some problems of spatial planning may indeed seem impossible, however, the self-same impossibility has always intrigued him. His way of thinking is marked by spatial structuredness and ability to find causality in complex connections providing his perception and argumentation with a particular grasp. Would it be possible to work with such a versatile topic as a functioning common space in any other way?

Interviewed by Kaja Pae

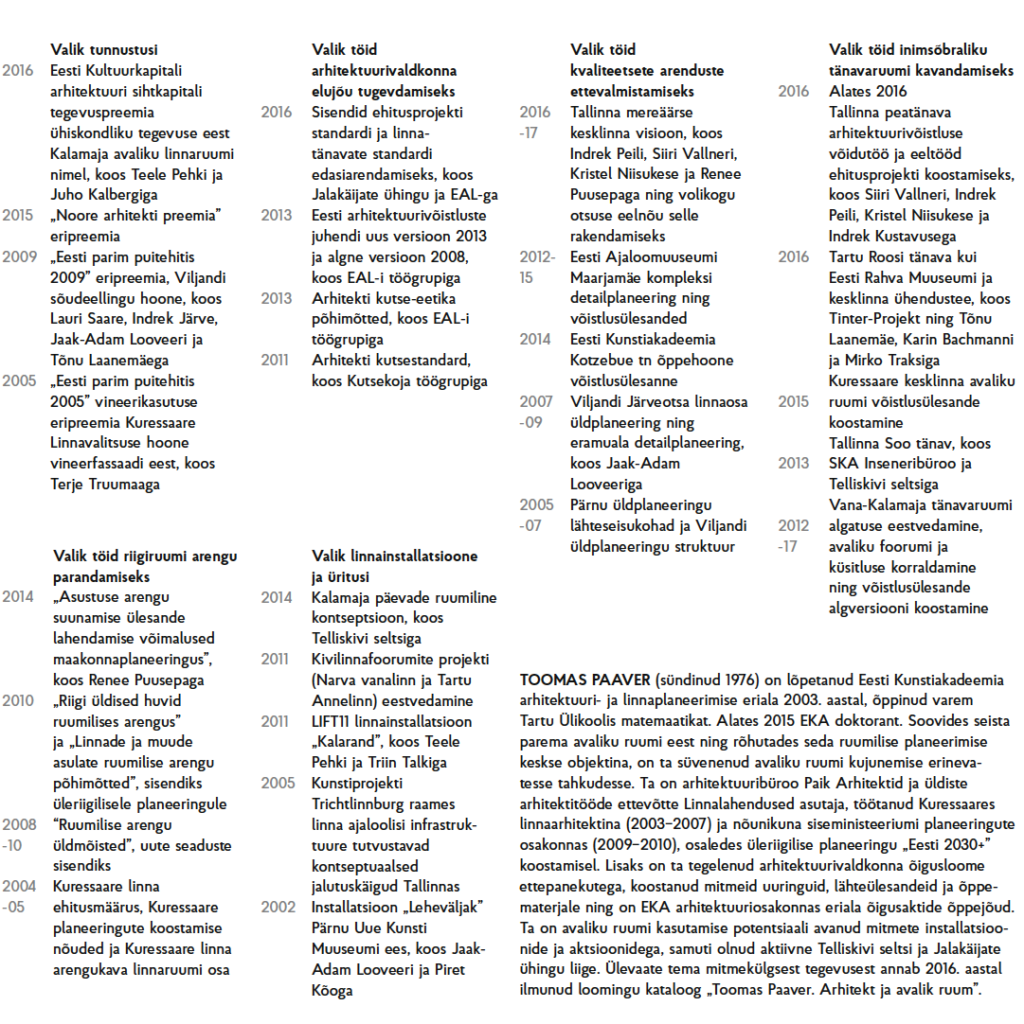

TOOMAS PAAVER (1976) graduated from the Department of Architecture and Urban Design at the Estonian Academy of Arts in 2003 having earlier studied mathematics in Tartu University. He began his doctoral studies at EAA in 2015. With the aim of standing for better public space and stressing it as the core object of spatial design, he has delved into the various facets of the development of public space. He is a founder of architecture office Paik Arhitektid and more general architectural service provider Linnalahendused, he has worked as the city architect of Kuressaare (2003-2007) and an advisor in the Planning Department of the Ministry of the Interior (2009-2010) participating in the development of the national spatial plan “Eesti 2030+”. He has also been active in proposing legislative motions in the field of architecture, conducted various research studies, terms of reference and study materials, and worked as a lecturer of speciality legislation at the Faculty of Architecture at EAA. He has similarly investigated the potential of the use of public space in installations and campaigns and been an active member in civic associations Telliskivi Selts and Jalakäijate Ühing. An overview of his versatile activities is provided in the catalogue „Toomas Paaver. Arhitekt ja avalik ruum” (“Toomas Paaver. Architect and Public Space”) published in 2016.

Which spaces (I mean exterior spaces) in Estonia do you consider important and pleasant? Why do these spaces speak to you, where does their value lie?

When thinking about exterior spaces, I tend to consider the structure of spaces rather than a single space. When thinking about the question in detail, I came to a comparison. A building may also be considered as a structure of spaces. You can look for a highly pleasing interior space there, but architects do not usually view buildings like that. Also, a good exterior space consists of numerous different and interactive smaller spaces. The broader structure of small spaces is more important than the small space alone. Compared to buildings, it is important to understand in the design and construction of exterior space that the latter is not created as a result of a single construction. Some parts of the exterior space may be built and re-built, but it will still continue in so many directions and also inside the buildings. The construction, demolition, reconstruction or change of function of any adjacent building will also shape the exterior space. It’s interesting to note that when I try to name some examples of good places, I get images of various spaces in the structure of old city districts, either streets, courtyards or squares.

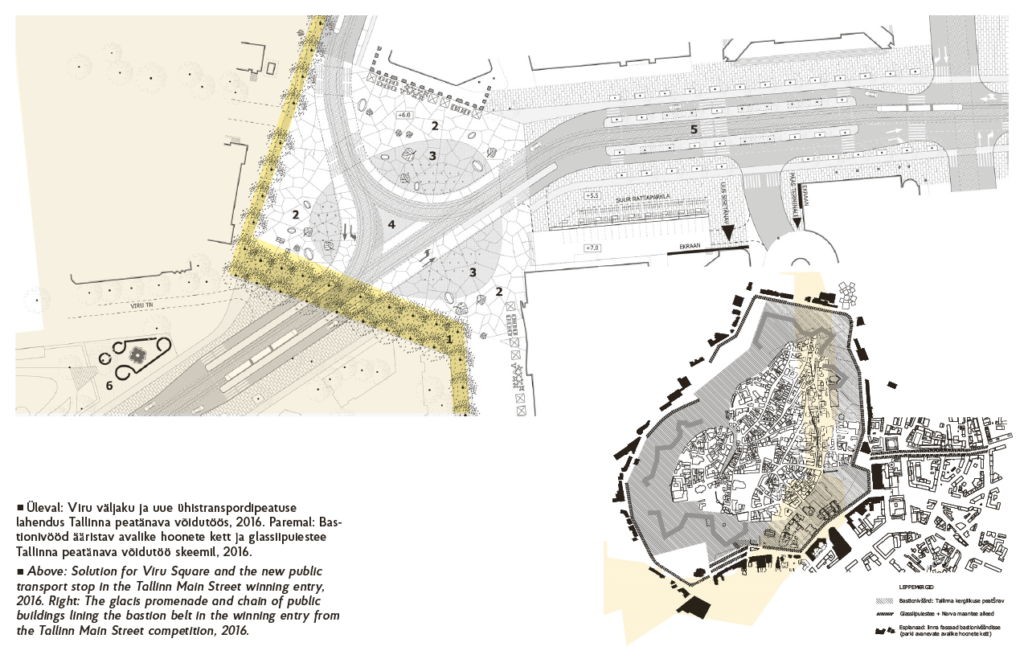

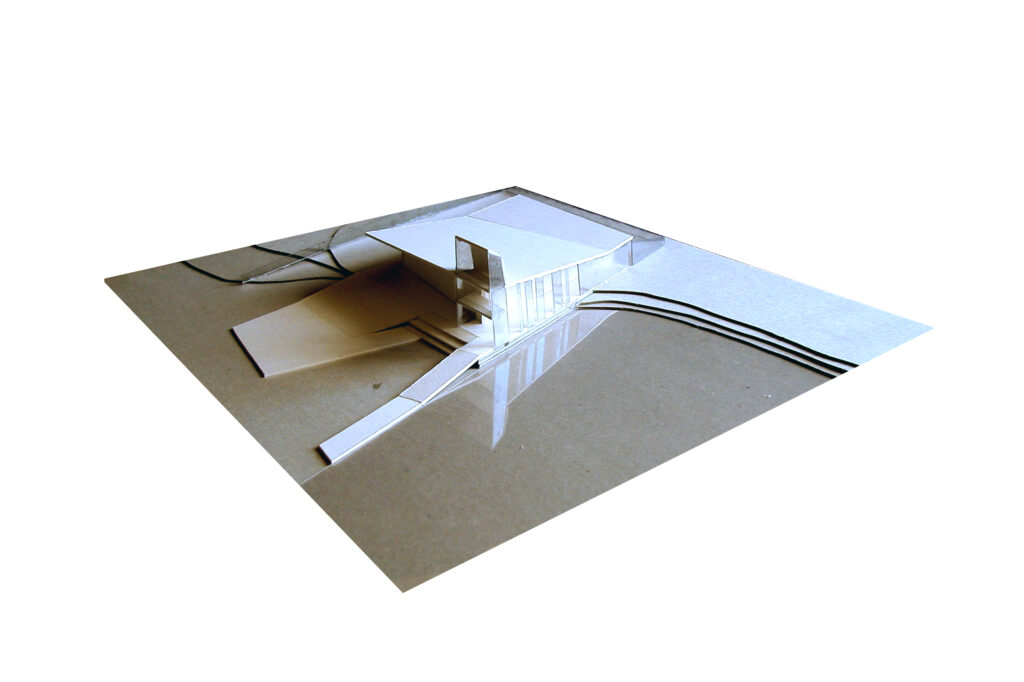

You have mentioned the glacis promenade1 in Tallinn as an important connecting space, and it also plays an important role in restoring the original comprehensiveness in the Main Street of Tallinn project that you participate in. It seems to me that distinctive connecting and structuring spaces are not acknowledged on a large scale and it is also difficult to implement them gradually by single projects in the contemporary spatial design practice. Could you explain and give some examples of the value of connecting spaces and the key issues in their design?

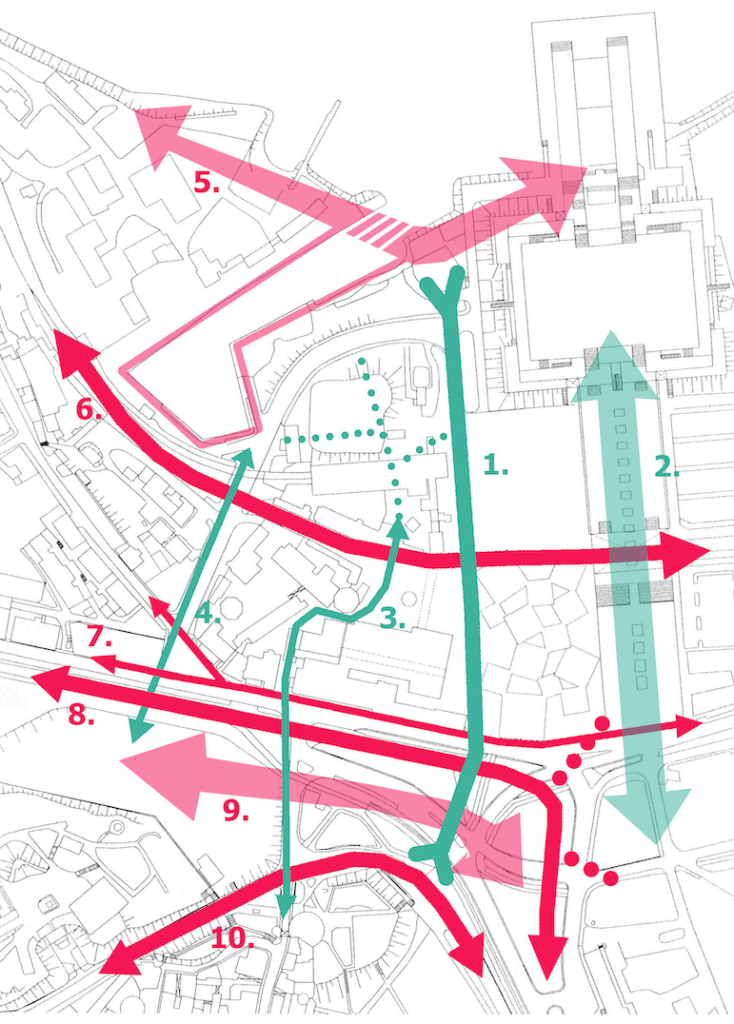

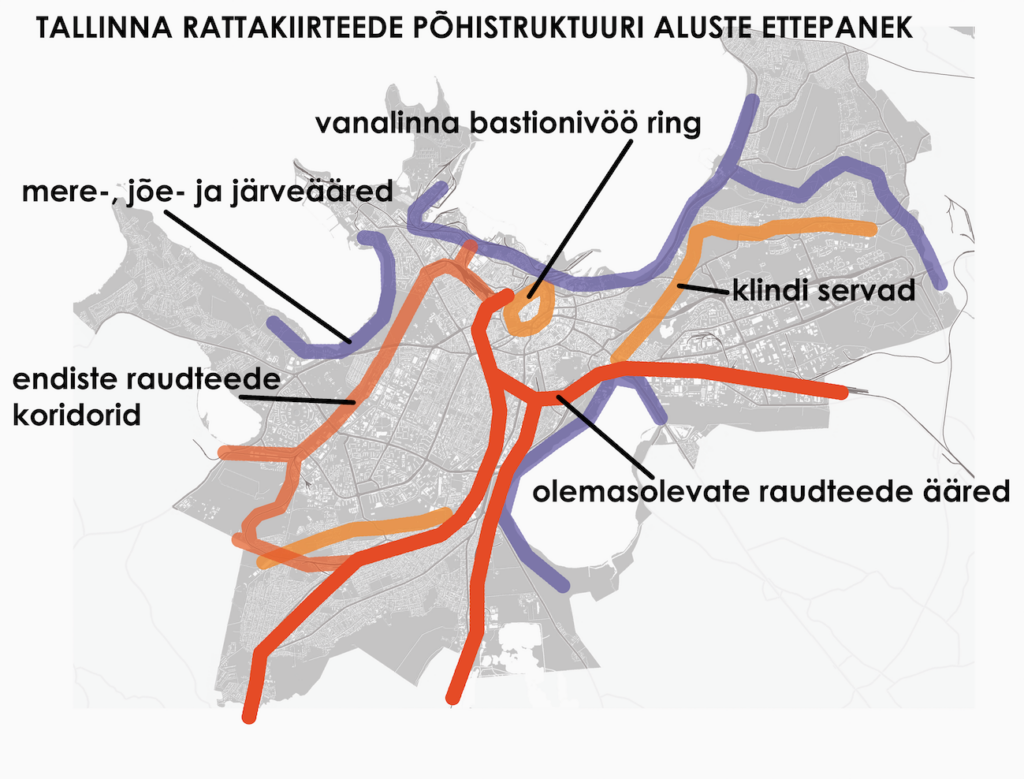

In the rediscovery of the glacis promenade on the bastion belt perimeter, the role of Kavakava architects is much more important than mine as they know how to notice such spatial elements and their potential in the future space. I have also instinctively considered the parts of the promenade sacred, but before our cooperation in the main street vision composition, I had not acknowledged it as such a forceful element. Now I have become an ardent fan of the glacis promenade. With its mere existence, it has quietly created the structure of the city centre for more than a century and had an unobtrusive influence on a large number of single projects that the authors may not have even been aware of. Its primary value for the future lies in the fact that with the help of the present connections, the central part of Tallinn could be turned into an almost human-scale city with very inexpensive moves. I think that in the development of a good city, it is crucial how the space with its comprehensiveness allows to guide people while also providing change. It seems that when people do not have to think about finding their way and they are not bored, the distances become shorter. The surroundings of the glacis promenade already offer forceful variety, but its comprehensive continuity can be perceived only in sections, for instance, from the Creative Hub to Balti Railway Station. It is now important to mend the former mistakes, that is, the disruptions in the junctions by underlining the crossings along the promenade. Viru Square is one of the disruptions. The next step is to create a unanimous and consistent sense of space on the roundabout by improving the present avenue with matching pavement, urban design elements and missing trees. Once we do that, we will bring several symbolic buildings of Tallinn closer together, for instance, Estonia Theatre, Viru Centre, Rotermanni Salt Storage, City Hall, the Creative Hub, the new building of the Estonian Academy of Arts, Balti Railway Station, the National Library, City Government etc together with the whole Old Town. In order to implement the vision efficiently, every single branching road must be cleverly connected – including, for instance, also Soo Street which was completed as a kind of an example. Anyhow, the key question in case of implementing such a connecting and structuring space cannot be a plan or a single construction project, it can only be the determined and longstanding work by someone who has the opportunity to interfere with each respective activity as they arise.

You are a rare breed of architects in the sense that you have searched for various means for working with public space in various positions. Your activities clearly reflect the need to find ways how an architect could be involved in the design of public spaces in a more fruitful and versatile manner. What are in your opinion the main bottlenecks today in Estonia obstructing the design and realisation of good public spaces?

It seems that individual bottlenecks cannot be highlighted as there has been no significant, conscious and comprehensive work done on the development of public spaces in Estonia. It has often been used as a rather lofty statement to make something look better. Good things have often resulted from lucky coincidences or the work of individual enthusiasts, architects or officials. in terms of the development of the society, I have considered it important and also as my mission that citizens or officials have a better understanding of the essence of the work of an architect. And at the same time also that architects would foresee better what would be important for a common citizen. Perhaps it could be said that the most discouraging aspect is the prevalence of incomprehensibility and old obsessions.

Could you describe your work as a mediator between architecture and society some more? What makes the given interpretation difficult?

For instance, when I worked as a ministerial official, I heard numerous suspicious statements about the profession of the architect, such as “the architect always wants to build a monument to himself” or even “the architect wants to be God” and at the same time also lines like “the architect is just a whore in the arms of the developer”. It is obviously difficult to explain the essence of the profession to a person with such convictions. Although there might sometimes be a trace of truth in such statements, these people cannot suggest anything better that could replace the work of an architect in the society. Architects themselves do not really bother to argue with outsiders but calmly continue with their work. Then again, people with no understanding of the architect’s profession write documents organising the architect’s work or thoughtlessly change the living environment. In my opinion, it is important to deal with this issue. For instance, already a while ago I worked up enthusiasm for looking for verbal formulations corresponding to the essence of the work of an architect to use in various documents and to passionately stand up for them. Because if the society is imbued with misconceptions and suspicion, there is no way to make it function properly and improve the space as a whole.

On a more positive note, I do also see signs of some slow improvement in the society. For instance, I would like to applaud the series “Ruum” (“Space”) on ETV (by the Estonian Centre of Architecture and Ylle Rajasaar, content editor Piret Jürman, director Marta Pulk)persuasively conveying that the work of an architect is not so much about creating works of art or taking commissions, but clearly directed to people and the whole society. And finally, I must add that I have attempted to get the social consciousness abandon the obsession with the architect as an almighty planner, as there can never be such a thing. Instead, I have tried to suggest a notion that in addition to buildings, architects also work with public space with all the mutual interconnections, set the respective tasks and perceive the spatial connections at large.

When talking about public space, we sometimes hear a legitimate concern for Estonia turning into a so-called boring Nordic country, for instance, the standard bicycle and pedestrian roads next to the streets have a monotonous effect – albeit planned with the good aim of allowing healthier ways of travel, they seem like non-places – and due to the anonymity you do not necessarily know if you are on Saaremaa or in Võru county. Then again, our colourful history provides plenty of material for a more individual approach to public space considering our layers imbued with Finno-Ugric, Nordic and East-European features. What would you underscore as the characteristic features of the Estonian public space? How could we avoid the formalisation of public space that has taken place in several welfare societies?

Development projects could naturally be made more versatile if we add the creative contribution of architects in the engineering-based approach taken in the public space design process, it is definitely necessary, however, it would be a common answer with little signification. I would begin with a wider principle: a specific era produces a specific kind of space. It seems to me that at least in some sense it is indisputable and perhaps even more defining than choosing the architect. I feel that the most important aspect in creating the peculiarities of the place and the variety of the space is the relation to the previous eras, as there was already something everywhere. Eras must complement one another. I also believe that it is futile to wish that the whole space be new and so to say proper. Just as there are people of various ages in a healthy city, also the built environment should exhibit versatility in age. A part of the space should be deteriorated, overgrown and old to a varying degree. It can apply to both buildings and cycling and pedestrian roads. Everything always develops slowly in Estonia and before some extensive planning solutions are completed, a whole new era has begun. This has considerably increased the diversity of our environment, but sometimes perhaps also created some confusion in the space. This leads me to the illustration, I have nothing against or rather I even like it when a new cycling or pedestrian road at one point continues as a simple old gravel path that was perhaps used for the same purpose already decades ago. It is important to do it so that roads would not end with a so-called temporary dead-end. If we think that every new building added at any time always ties the space together, then that is how we connect eras and avoid formalisation, as we cannot possibly build or even renovate everything together, but the space must improve. So, all in all, I believe that Estonia could easily and bravely highlight its small size and poverty because appreciating what we have is actually our strength. Thus, we could verbalise a proper principle for the development of the Estonian space, accentuation of its peculiarities and avoidance of formalisation: let’s move on in small but sensible steps.

Your reply highlights what a great resource the passing of time is to an architect and how valuable are layers of time due to their inherent diversity and linkages. And yet we cannot handle the temporal dimension well in the present planning system.

In my opinion, the present planning system is not suitable for that. The greatest essential controversy lies in the adoption decision following the long and lofty processing procedure. It seems that such a decision-making model wants to stop time. As we know, time cannot be stopped no matter how powerful the laws. The actual space lives on and changes, people’s perceptions develop, architects’ visions progress and even the paper written in stone lives and transforms through its interpretations. In practice, the interpretations are based on and thus also the adoption is mainly influenced by someone’s legitimate expectation of something but not of a good space as this is too vague for the system. But most people do not know that the building rights and intended uses are even vaguer, albeit seemingly highly strict. Due to these adoptions, the society is under the delusion that this is how a space is created while the reality is somewhat different. Well, actually I have also experience that you can live with these adopted documents. But only if the interpretations are made by officials who think spatially, creatively and skilfully in general interests. What I want to say is that most of all we need more creative officials in the public sector. Spatial planning will remain necessary also in the future and it must become freer in form, but in legislation I would discard the long-term building rights arising from the adoption decision altogether as these seem to be remnants of the 20th century. At present, the society is not mature enough to understand it, but I’m sure we will reach it one day.

Continuing with the dimension of time – the protection of historic architecture is relatively well acknowledged here, however, we cannot protect their relation to the network of contemporary connections and functions (including the city network) which is highly important for the user and through the usage also retains the relevance of the object.

Let’s take a random current example that has not been discussed much. Tallinn recently initiated the preparation of the detail plan for the construction of a large hospital in Lasnamäe that would eliminate all the former hospitals which were carefully fitted into the city structure. Does anyone ever think what a serious impact such a decision would have on the city structure and urban life and how small and insignificant is actually the detail plan of one plot in Lasnamäe? The latter will give us the number of floors and the surface area under construction, but who cares about that? People are interested in the fate of the old hospital network, convenient routes to hospitals and whether they now have to travel to a huge suburban medical factory to see a specialist.

What have been your most interesting or significant activities in the area of public space? Which results have surprised you?

If we take the activities related to the roads within the district of Kalamaja as a significant example, I have been surprised that the changes in Soo Street were noted to such extent. When I was conceptualising the street issue some time in 2012 during the most active period of the neighbourhood association Telliskivi Selts, I primarily concentrated on Vana-Kalamaja Street as the main representative object that the change could draw attention to. A good connection between the Old Town and the sea would be relevant for the whole city. It now seems that the city has taken the initiative of Vana-Kalamaja over, although it indeed took a while. At the time, Soo Street seemed like a quick solution to an elementary problem, much like tidying up your neighbourhood. Soo Street was completed in 2013 and it partly served the same purpose that I had set for Vana-Kalamaja initiative in my mind.

Soo Street has become a symbolic example of how to make the street space suitable for various users and how small polished nuances can make a street comfortable for people. What was your initial aim for Vana-Kalamaja Street initiative and what is the essence of the architecture of Soo Street?

The mission of Vana-Kalamaja initiative was to make the society acknowledge the need for working with comprehensive street spaces that was non-existent at the time. The street design process did not include any cooperation with architects or citizens although the majority of public space consists of streets. I am glad to see that in the past five years at least there has been more discussion of the topic. Soo Street was built cheaply at the time, street furniture etc were completely out of the question. It may be surprising that there is actually not much else except asphalt, but the space works. In hindsight, it is a validation that as an architect I was doing the right thing with a little detail requiring also a battle in my own circle, the non-architect members of Telliskivi Selts. It is the row of low streetlights in the middle. I dare to think that if you remove or rearrange the lights now or even make them higher, Soo Street would seem just another street with a wide pavement with no symbolic effect. Streets need some kind of a pervading spatial idea with the right proportion that allows you to recognise the particular street. Sometimes a few simple elements are enough, especially if you are building on a low budget. Perhaps the architecture of the street space means that the spatial solution, greater pervading ideas and small nuances have been envisioned at the same time with sensitivity and care.

You have researched public space as a scientist in a sense that you have carefully studied the various forces shaping it – you have delved into legislation, participated in the active civic association Telliskivi Selts and worked as the city architect in Kuressaare. What are the questions and issues that interest you most at the moment? Is there anything else that makes you want to understand how it functions?

I have begun compiling my practise-based doctoral thesis with the aim of combining the various activities and setting them in a wider context. Its working title is “Architect in Social Roles”. It could be said that my work and activities began in planning and I understood long ago that plans actually do not function in the way they are described. The practise so far has shown that the important moves are made otherwise. These could be investment and funding decisions, selections of location, land purchases, development plans, general standards, coalition agreements or terms of reference, draft plans of building projects, terms of architecture competitions, the decisions by competition committees, some civic activities, agreements between important stakeholders etc. Very rarely of course also something significant is achieved with a plan, but mostly they are made merely for formalisation. At least in Estonia. Plans are presented to citizens as a means of cooperation, although the draft plans would actually be a much clearer basis for cooperation. Plans have a highly important role, for instance, in creating the ownership structure, it could also be so in creating the general structure of public space and agreeing on the principles, but it still constitutes only a small fraction of spatial design. It is important to consider all factors all the time, before and after each plan. For instance, the current Tallinn Main Street development has not been a part of any plan, instead it could be considered contradictory to the earlier valid plans. Yet, we believe that this is precisely what we need and this time also the city interprets the plans within public interests, which should be the elementary course of action but in Estonia rather innovative. The remaining issues are solved by cooperation and the construction project. It is my understanding that in Estonia there is no point in dreaming about a system where carefully processed and adopted detail plans would form the basis for spatial development. It will not work anyway and in case you wish to make it work, it will be highly forced resulting in the creation of too monotonous spaces. Now we come to the most important question – if plans do not work, what could we suggest instead. There is no easy answer to that, however, I have a hunch that I will develop in my thesis.

Could you shed some light on your hunch? What could help us towards more thoroughly reasoned public spaces? The conscious creation of public spaces requires activities on various scales – from the details shaping the spatial experience to the big picture on the national scale as well as recognising and combining various areas influencing the space. Public space is such a structural issue that I sometimes feel we need some kind of a common denominator or a wider comprehensible preconceived idea to join and shape various scales and areas while also remaining actually understandable to all stakeholders.

Isn’t “public space” itself a sufficiently strong common denominator when used in the sense of physical space and conceptualised as a network connecting all constructions? Our legislation and practise have not been able to use the word, but such an object exists in space and should be understandable to everybody. Anyhow, public space as an object with vague borderlines and connections requires both very general and very detailed continuous work by an architect with a very long and short perspective in time. It is somewhat different from the work resulting in a construction project that builders use to construct the building. When analysing my own work so far, I found an umbrella term in English – public architect. Here I see in practise the common features and general aims across various roles, scales and timeframes. One common feature is that all the roles are bound to be connected with the public sector. The other is that working with public space in depth, sensitivity to the society and rights as well as the architect’s sensitivity to space all combined can replace the functions of bureaucratic documents.

I know from experience that without analysing and solving buildings thoroughly at school you will not develop a sufficient feel of public space solutions. The architecture education at the Estonian Academy of Arts is highly valuable and necessary and it must be retained as it provides the basics for spatial design. In my doctoral thesis, I can think about ways to add social wisdom to the education of architects allowing them work in the public sector and the changing world around us. In a way that we would have enough architects who feel at ease in the 21st century institutions transforming them bottom-up, in their daily work with public space in private ownership, with structuring it and creating connections, taking the right steps at the right time and in the right place, in consideration with people’s lives, rights and expectations and everything else that is essential and timeless.

You have pushed the boundaries in so many ways and proven with your activities once more that there are different ways to work in architecture, I believe you do not make any drawings at the moment? What are you doing and what are your plans for the future?

I usually envision drawings in my imagination. I believe I am not an architect in the conventional sense of the word, however, the fact that you ask me this question allows me to believe that a person like me is necessary for architecture. I would perhaps even make some drawings, but my hand movements are no longer precise, much like my legs. Therefore, my personal future is a rather difficult issue, as my possibilities will be increasingly limited with time. Fortunately, I can still write on keyboard and think positively. I have been forced to decrease my workload, but I intend to complete the Main Street of Tallinn project and my doctoral thesis. As to the form of my future work, I can say that I have acquired enough experience how to do architecture in a free-spirited atmosphere also with words.

HEADER photo by Mark Raidpere

PUBLISHED: Maja 91 (autumn 2017) with main topic Shared Space

1 The promenade at the perimeter of the fortification zone.