We are asking how the European Union, local government and the architectural office can contribute to the development of architectural thought?

VERONIKA VALK-SISKA

Chair of the EU Member State expert group on ‘High-quality architecture and built environment for everyone’, adviser on architecture and design at the Ministry of Culture

Kaja Pae: What are the priorities in spatial development in the European Union and the European Commission, and how is their implementation supported? Are there any new topics on the table?

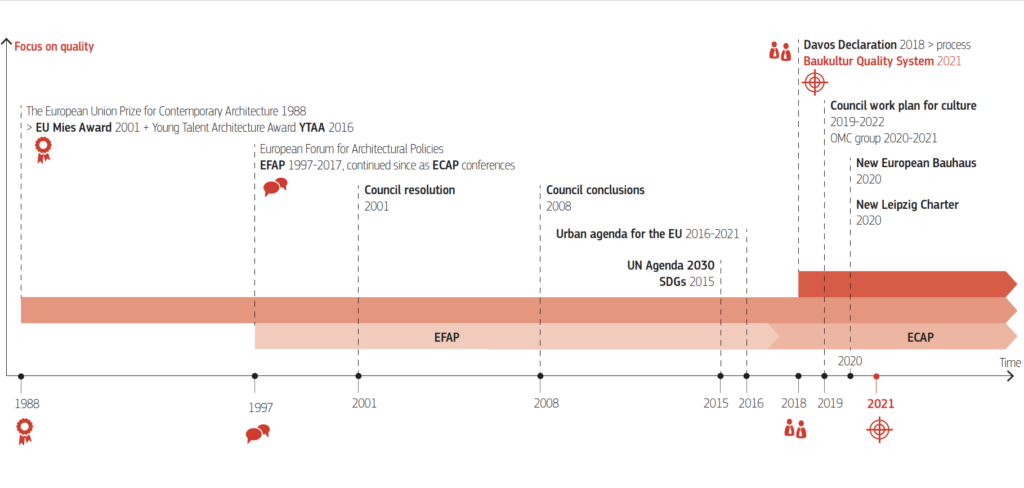

Past decades have paved the way to a more holistic approach to the quality of the living environment.

The New European Bauhaus (under the slogan: beautiful, sustainable, together) is on that timeline a recent initiative to accelerate the implementation of the Green Deal by making the solutions more appealing and accessible. The New European Bauhaus is significant because it highlights the role of architects and designers in bridging the knowledge and skills of different fields of life. The New European Bauhaus is not seen as a separate policy or program at EU level, but it can be seen as an awareness-raising campaign that reinforces itself through other ongoing activities.1

Kaja Pae: Architects have complained that design competitions are no longer a place to present visionary ideas for the living environment. Real estate developers do not tend to ask for them, either. Research and experiments in universities are mostly at the level of prototypes, and at best we see them displayed in architectural exhibitions. Where and how can spatial design visions be born today? How can the institutions of the European Union and the Estonian state support the creation of visions for the living environment?

The answer depends on what is considered a visionary idea, and whether it is important to present it or also to implement it. One of the important features of a visionary idea is that it has a cultural dimension. Architects are those who carry the cultural dimension in creating the living environment, just as designers do in developing products and services. It would be good if the clients always valued the living environment as a carrier of culture, but we are not there yet as a society.

Who supports the development of the cultural dimension in spatial design or in entrepreneurship? So far, the Cultural Endowment has gratefully supported the organisation of architectural competitions and events, and to a certain extent creation of experimental projects. The question is whether only these exhibitions, publications and experimental projects are sufficient to properly develop the cultural dimension in architecture and design, to advance a space of thought and spatial culture.

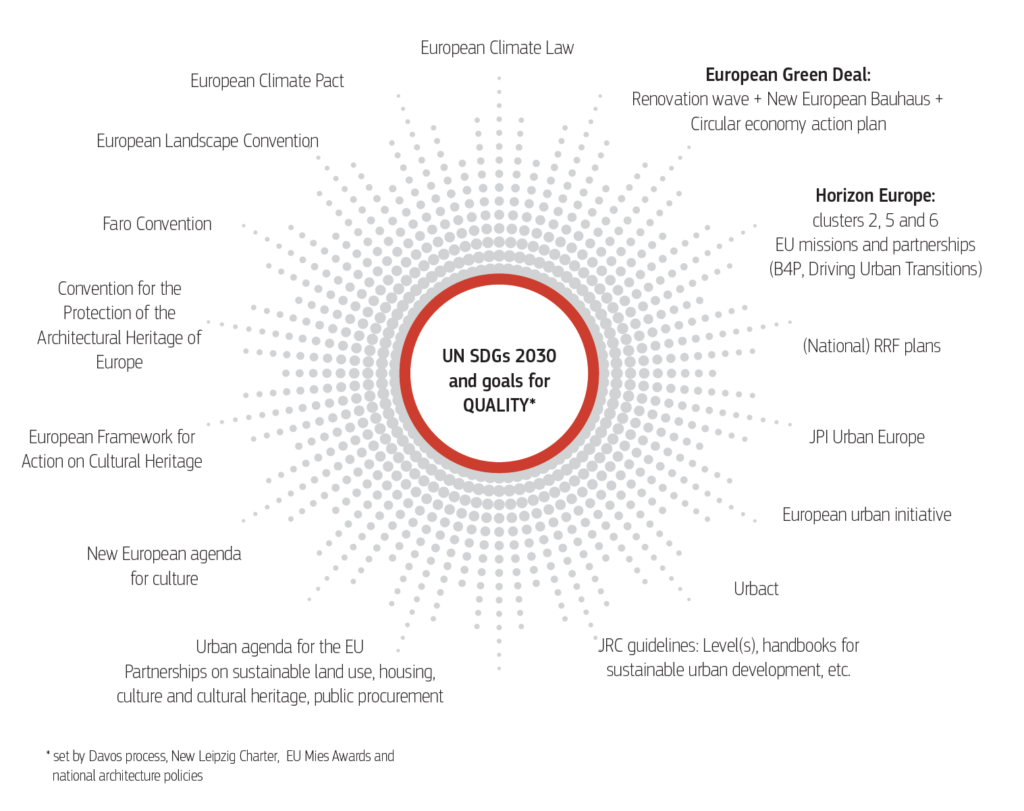

What about the implementation of visionary ideas? It is tied to urban (or, design) governance, i.e., planning and use of resources (time, human, financial, material, etc.) to improve the living environment. This process can have visionary outcomes when the parties—the client, the architect, and the user (inhabitant)—dare to make bold decisions. Such spatial decisions can be born when there is a holistic approach to making spatial decisions that integrate the cultural dimension of the living environment with other quality aspects. For the first time at European level, such an integrated approach is now available in the form of the Davos Baukultur quality system, published in May 2020.2 The EU and the state can support quality-driven placemaking by contributing to the spread of a value-based procurement model and the broader adoption of a comprehensive evaluation system in spatial decisions in both the public and private sectors, thus promoting the cultural dimension.3

By Estonian regulation, the local government has extensive autonomy in shaping its spatial development, as it should take place close to the inhabitants. At the European level, it is thus important to foster capacity building within all administrative levels, especially the local governments, and share international experience and best practices. It is difficult to underestimate the role of city and municipality architects in implementing well-informed and holistic visions for the living environment. In 2021–2022, the Estonian Centre for Architecture has undertaken an extensive spatial development training programme for both state and local government officials. As described in Estonia’s development plan for culture 2021–2030,4 local governments would also need a national competence centre to support decision-making processes.

Kaja Pae: What spatial development topics that need to be addressed and that would also create new opportunities would you like to emphasise? Both on a global scale and for Estonia?

First, we need to mention the ‘green shift’, which in the broadest sense means the reversal of anthropogenic climate change. For people’s behaviour to become more environmentally conscious, a cultural shift is needed, which can be driven by the public sector as well as the cultural sector. So far, the impact that the field of culture could have on changing the thought patterns of society regarding the ‘green shift’ has not been properly considered in Estonia. Changing the consumer (or, prosumer) culture also affects companies. Viewed in that light, as a cultural shift, it is a question of spatial education and awareness. Both the School of Architecture in Estonia and other similar ventures elsewhere in Europe (e.g., Poland, Finland, Norway)5 give the new generation the opportunity to imagine and shape a better living environment.

Estonia directs significant investments to the housing stock, railway, road, school, healthcare, and other networks, etc. Culture and heritage should be emphasised much more in the procurement processes, support instruments’ selection methodology and project evaluation criteria. All investments, regulatory frameworks, and allocation of EU funding programmes (cohesion policy funds, the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development, Horizon Europe and its relevant missions, Creative Europe, and Erasmus+, among others), along with national, regional and local funding and investment opportunities, must contribute to the quality of the living environment. This can be done by integrating the Davos Baukultur quality system in the procedures and implementing a value-based procurement model. It is crucial to include a holistic approach to quality in all spatial decision-making processes.

In Estonia, the ‘percentage law’—Commissioning of Artworks Act—, which currently regulates the commissioning of art at public buildings, should also be amended. This law should be extended to urban and infrastructure projects, so that a specifically designated part of their construction budget is spent on landscape architecture, as is the case in many parts of Europe.

Kaja Pae: Please highlight a project that you appreciate for its ability to meet today’s challenges and that is visionary in the best sense of the word.

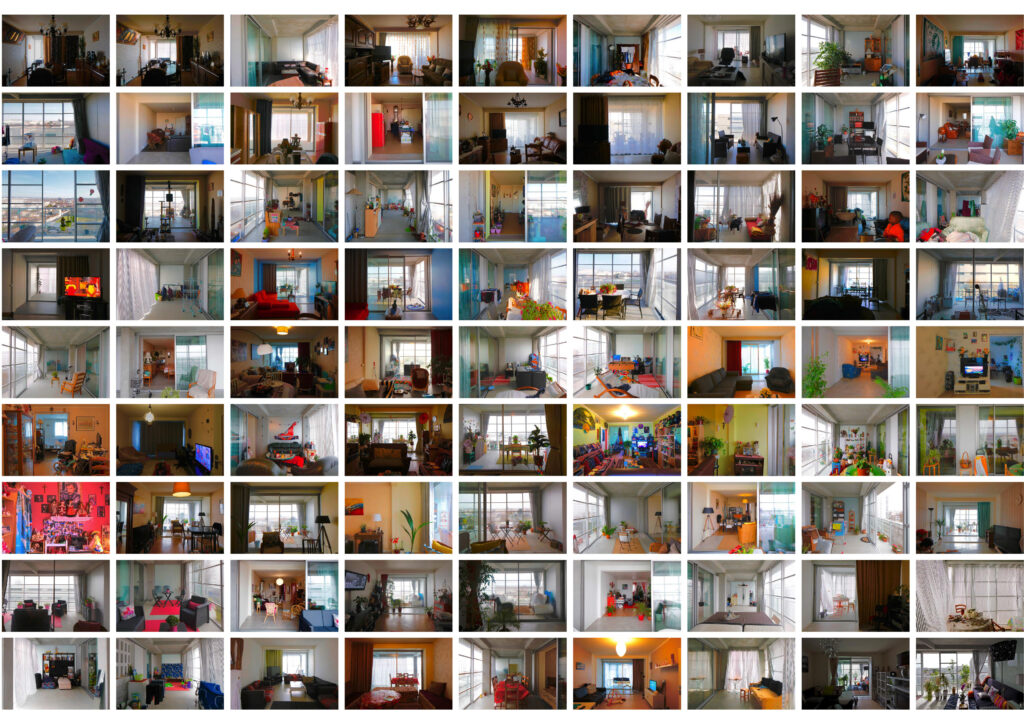

Recipient of the EU Mies Award (2019), the transformation of three social housing blocks from 1960s in Cité du Grand Parc in Bordeaux, France, shows how to align the needs of the community with the renovation process. Tenants of 530 homes were not moved out during the reconstruction that was based on the quality of the interior, resulting in more space, light, better views, an upgrade of facilities, and a significant improvement on energy efficiency without increasing rents. Lacaton Vassal architects won the Pritzker Prize in 2021 for commitment to high design quality and success of the participation model, replicable throughout Europe.

Approximately 700,000 dwellings await reconstruction in Estonia, as the reconstruction rate will double in the next 10 years. Regarding prefabricated housing areas, it is important to involve the residents in co-creation processes and to apply a holistic value-based approach in ensuring the integrity of the living environment.

PACO ULMAN

Architect at the Competence Centre for Spatial Design at the Tallinn Strategic Management Office

KAIDI PÕLDOJA

Executive manager of the Competence Centre for Spatial Design at the Tallinn Strategic Management Office

Kaja Pae: Architects are voicing their concerns about architectural competitions having changed so much that bold concept proposals no longer have an outlet. Real estate developers are not too keen on organising vision competitions, either. Research conducted at universities mostly remains prototypical, with the main output being architecture exhibitions. Where is the modern place for visionary spatial design and how does it come to fruition? How does the Competence Centre for Spatial Design at the Tallinn Strategic Management Office see its role in the development of spatial vision concepts?

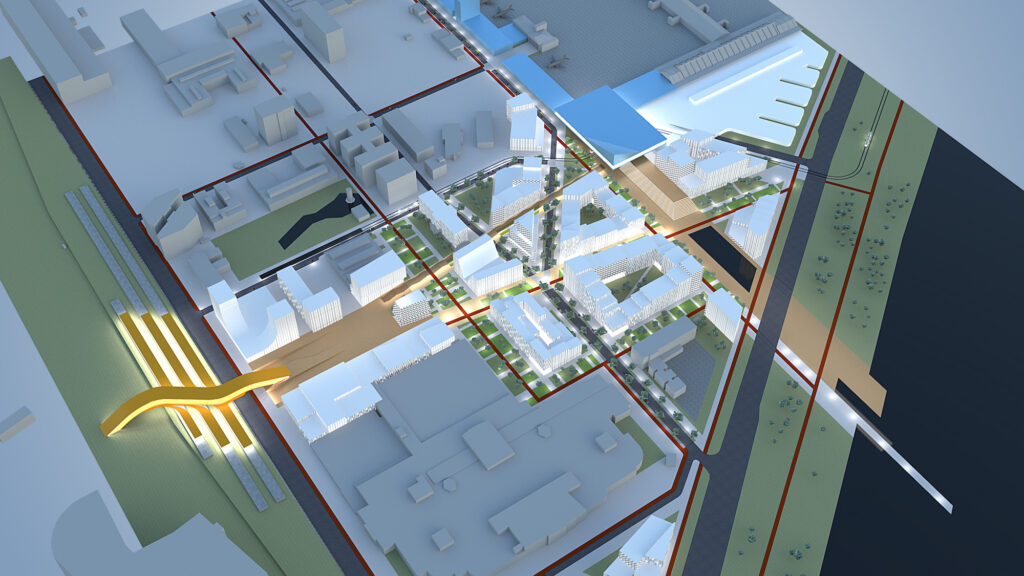

Tallinn’s Competence Centre for Spatial Design is an interdisciplinary practice for spatial planning and architecture. We work across a variety of scales: from supra-regional collaboration to themes covering the entire city (planning of the blue-green-network), from compiling general design plans to consultancy work regarding specific sites. Developing spatial visions and organising architectural competitions enable to improve the quality of urban space in a short time. Equally, the guiding principle of the team is to deal with long-term strategic planning topics as well as everyday spatial decision-making. We maintain international collaboration with other cities and research establishments, developing novel methods of public participation such as the community engagement application AvaLinn and the virtual reality application AvaLinn AR. We have several ongoing projects where collaboration with universities does not remain merely prototypical: these are the modular kindergartens in North-Tallinn (the vision competition will be announced shortly), ongoing collaboration with the Estonian Academy of Arts in the form of the ‘City Unfinished’ project, as well as Tallinn’s Participation Hub which is planned in collaboration with Tallinn University of Technology.

As practicing architects, we understand the criticism towards architectural competitions. We can identify several problem areas, firstly, the contests have indeed become extremely regimented which does not leave much room for more creative interpretations of the brief. Secondly, architectural offices are under economic pressure to win as many competitions as possible. For the average Estonian architectural office, time invested in participating in a competition is an investment that is most likely not to yield a return. In order to circumvent risk, solutions that are familiar and which have worked before, end up being repurposed. Additionally, now there are so many architectural competitions taking place and the organisers of the competitions are not getting high-quality results since participation levels are low. Worst of all is that architectural competitions have oftentimes become the basis for legitimising bad strategic planning decisions.

One possibility to retrieve contemporary and high-quality solutions is to start from higher up, i.e., by getting involved in the discussions and decision-making on what to plan and where to build.

One of the key roles of the Competence Centre for Spatial Design in Tallinn is to ensure better decision-making regarding the selection of sites for public buildings and spatial conceptualisation of extensive development areas prior to the start of the competitions.

We have a clear desire to support politicians in making better spatial decisions looking farther, and deeper, into the future. The intricacies of Tallinn and the sheer pace of the city’s growth require both a wider view of the region as well as intervention on a one-to-one scale. It is also important to acknowledge that decisions seemingly made outside the realm of spatial design (e.g., a decision to establish a state high school) can have significant and complex effects on the built environment.

Kaja Pae: What are some of the novel topics and projects currently in the works at the Tallinn Strategic Management Office? Please elaborate on an ongoing project at the strategic management office that you value based on its precision to tackle contemporary challenges, one that is visionary in the best sense of the word.

Short-term actions are influenced by the need to conceptualise the transition towards green economy and challenges revolving around climate change. This ensures that all significant ventures are tied to these topics in one way or another. Informing the green corridor concept from both the point of view of sustainable modes of mobility as well as biodiversity has been one of our most successful endeavours so far. For example, the Pollinator Highway joining the bastion zone green areas with Hiiu district helps insects find their way to the city centre. It has turned into somewhat of a symbolic project, generating plenty of interest and positive feedback. The project is composed of numerous elements, including collaboration with both local and international partners. I also noticed my neighbour using approaches advocated by the Pollinator Highway: when I asked why he is leaving part of his garden unmown, he replied this is what they do on the Pollinator Highway.

The strategic management office is also working on Glint Park that runs along the limestone glint of Lasnamäe from Tartu highway to the eastern city border. Such projects where detailed design is preceded by thorough analysis by city officials with one of the key inputs being community engagement may become the go-to approach when taking on complicated and large-scale urban development projects. Equally important are the implementation of the bicycle strategy, the vision for an intra-Tallinn commuter-rail, the concept of extending tramways, and creation of various mobility solutions: hubs and microhubs, or nodal stations, connecting trains, trams, buses, bicycles, and kick scooters.

Kaja Pae: What themes in spatial design would you like to highlight that need attention and which would generate new opportunities, both globally and locally for Estonia and Tallinn?

It often comes as an unpleasant surprise to owners and developers when the City deems necessary to intervene and commences urban planning in certain key places where urban grain and spatial development are muddled. It is seen as harassment, i.e., intervention into what is otherwise a liberal market economy. It is difficult to say what causes this—is it the habitual nonchalant attitude of the city government when it comes to implementing change, namely the City reacting to urban developments already in progress or, instead, a perpetual fear carried over from the Soviet planning practices. However, it is clear that no entity aside from the City or the State is able to implement substantial change in contemporary Estonia.

The current situation in which spatial visions are created by the City is considered innovative in Estonia’s context. Up to now, it’s been accepted the City merely assesses planning applications and its involvement ends with the creation of comprehensive plans and design specifications. For example, we consider ensuring the high quality of urban streets, a key element of the public realm, to be one of the daily battles of the Spatial Design team.

The city should actively participate in spatial design along with other parties, not as a stagnating agent to processes via legislation, but rather, as an innovator. City departments are larger and potentially more capable than other stakeholders and the City government is the partner that can actually implement change.

This requires a change in the City’s attitude, who oftentimes act as if they are ‘under siege’, but also change from the society at large where there is often a lack of understanding as to the reasoning and origins of certain decisions. Additionally, changes in legislation would enable more higher requirements of spatial quality from every decision.

ALVIN JÄRVING

Partner at architectural office Arhitekt Must

Kaja Pae: Architects are voicing their concerns about architectural competitions having changed so much that daring concept proposals no longer have an outlet. Real estate developers are not too keen on organising vision contests, either. Research carried out at universities mostly remains prototypical, at best showcasing the best results at architecture exhibitions. Where is the modern place for visionary spatial design and how does it come to fruition?

Spatial visions with serious potential to shape society are not project-based occurrences that can be brought to life in a short-term project-type approach. Ideation takes time and its components have to be tested, incubated and polished in all possible kinds of architectural media—that is, in collaboration with the client of the architecture, at architectural competitions, at university studios, and in writings on architecture. All these media have their own specific weaknesses—in practice, short-term goals and the urgency of the present moment are too dominant; at exhibitions and the forced scenarios of academic work, the constructed reality is often subjective. Next to spatial solutions, it is the preparation of the soil that is sometimes even more important so that the vision would have a place for landing.

Preparing the soil comes in many forms, a big part of it is public exposure—partaking in exhibitions, architects’ writings, published project concepts, the work done by the associations of the specialties, formulation of project briefs, architecture criticism. Throughout our practice at Arhitekt Must, we have repeatedly hidden the actual agenda of our competition entries, because the soil for the desired results is yet to be created. Pouring cream gravy over our projects has helped to win contests—at the same time, the cream gravy ends up being smoothly removed during the subsequent design and communication work, and we give our all to ensure that the desired core concept translates to a built product that generates the positions embedded in it.

Kaja Pae: What themes in spatial design would you like to highlight that are in need of attention and which would generate new possibilities, both globally and locally?

Architecture has not really responded to the pressing concerns of climate change—this is where we should be cultivating an entirely different mode of thought throughout projects than what we are currently doing. It is a time frame issue—at the moment, we are still circling around a 50-year life cycle for buildings when in fact we need dialogue on meeting requirements for perspectives as long as 500 or 1,000 years into the future. With regard to the resources necessary to construct buildings, a 50-year life span on the functionality of a building is like fast fashion that is basically incapable of meeting long-term requirements, be it made out of wood, concrete, or steel. Energy savings and energy production are much more easily solvable as issues compared to the functional and moral perseverance of the building. I believe this is where we need new terminology to describe the functionality of buildings, according to adaptable and non-adaptable programmes. A few steps further from here, we really should start considering long-term effects again—what defines a city throughout centuries, what makes up the spirit of a place, and what should architectural form be like when the content is in constant flux?

Kaja Pae: So, are revolutionary, i.e., disruptive changes even possible in architecture? Or is it that architecture can be evolutionary, or at best, maybe mildly revolutionary: where change is gradual and relatively painless for the participants, but consequences—total?

Exhibition, school, or competition works that remain on paper only may end up having great impact on later projects and/or the work of other architects. Since the direct effect of architects’ work through completed projects is relatively small, it is better for architects to think in terms of indirect impact. In my opinion, architects could have use for the term weak revolution (analogous to the concept of a weak place). That way, architecture enables itself to provide a spatial seed for producing change, not necessarily create a revolution, per se. Architecture can be a reason and a beginning point for action, but for this to occur, it should be consciously proffering weak place / weak vision, so as to instigate conflict in mental constructs and elicit use and action, further cooperation, and change.

Kaja Pae: Please elaborate on a project that you value based on its precision to tackle contemporary challenges, one that is visionary in the best sense of the word. I mean projects where the new is not new for the sake of newness, but something qualitatively new.

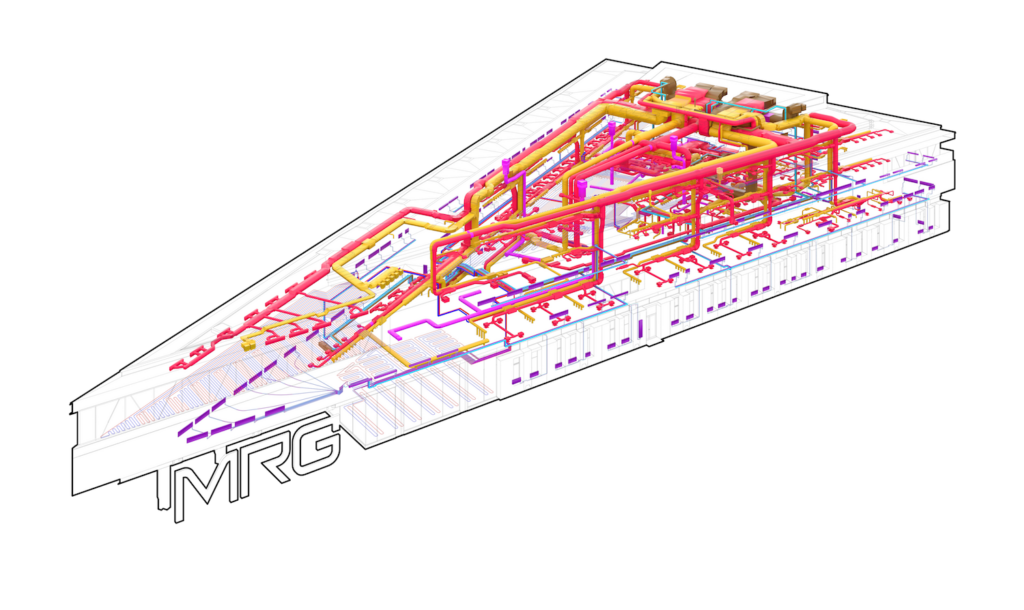

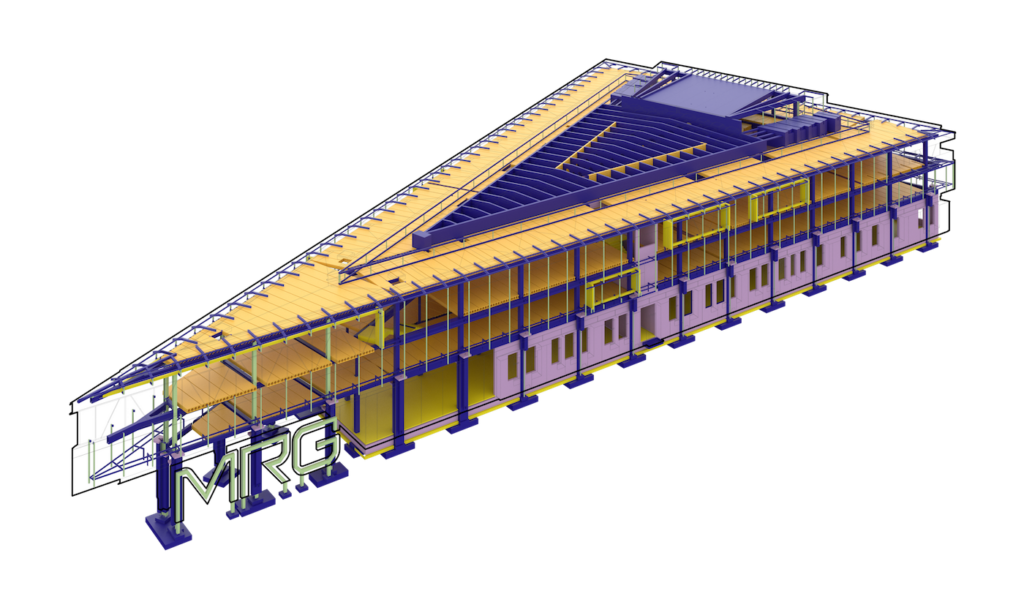

In our practice, our office has dealt with the abovenamed topics throughout several projects, but perhaps the most pertinent example would be Mustamäe State High School currently under construction. In a way, it is a very ordinary project—a school building planned onto the campus of Tallinn University of Technology, with quite a few of the conventional rooms. At the same time, it is a project designed to last in the fabric of urban space and programmes based on principles that are different compared to other modern schools: of all the rooms of the building, only the auditorium, the sanitary spaces of the assembly hall, and the kitchen servicing the diner have been designed as programmatically invariant typologies; all other spaces have been designed by capacities, and to capacity, to accept change. That is why ventilation injects into the building from the roof and the entire perimeter of the edifice is solved as a structure built of non-load-bearing walls, sensitive to a broad range of spatial programmes during the life cycle of the building. In so doing, the form of the building does not follow function as is customary, but form follows image and a pattern of motions that could define the urban space of the area for a long time to come. The spaceship-type design bounces off the technological bias of the school but is designed to shape thought patterns of the end users and provoke critical thought on the (built) environment and knowledge as humanity’s main vehicle into the future. All these ideas were covered under a veil of creamy visualisation during the competition entry phase but received emphasised focused attention during the design work that followed.

PUBLISHED: Maja 107 (winter 2022) with main topic Evolution or Revolution?

1 Further info: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2021%3A573%3AFIN&qid=1631781368249

2 Davos Baukultur Quality System offers the following eight criteria to assess the quality of a place: Governance, Functionality, Environment, Economy, Diversity, Context, Sense of Place and Beauty. Further info: https://davosdeclaration2018.ch/quality-system.

3 EU Council Conclusions 14534/21, https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-14534-2021-INIT/en/pdf. Also, in the recommendations by the EU Member State expert group, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/88649

4 Further info: https://www.kul.ee/kultuur2030.

5 See the EU Member State expert group report, p. 65, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/88649.

6 For instance, the Estonia’s recovery and resilience plan, https://rrf.ee.

7 According to the ‘Long-term strategy for building renovation’, https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/documents/ee_ltrs_2020.pdf.