The role of greenery as a climate hero cannot be measured only by the size of green areas or the number of trees. The Green Area Factor is the ability of the plot or area as a whole to balance the built environment’s climate impact.

Creating and maintaining the balance, variety and appropriate density of an urban environment require a good understanding of the big picture. Construction is fundamentally in spatial conflict with naturalness: one seems to exclude the other while both are needed for the comprehensive whole. Buildings and infrastructure need room and space, and urban greenery has to play its balancing role in rather meagre circumstances. Greenery’s main function is more than the sum of its various parts: comprehensively functioning ecological communities play a crucial role in mitigating the effects of climate change. It cannot merely appear in cities as a fashionable décor, it should be green for real: regulating the microclimate, supporting the water cycle, providing habitats for as many living beings as possible from microbes to urban wildlife as well as people.

But how to assess if we have enough green areas and if they serve their function? There are several methods from the readily available tool greenmeter (rohemeeter.ee) to specialised analyses of land data. Some of these were also explored in the winter issue of Maja focussing on smart cities.1

One of the many tools for determining the green environment quality on the planning level is the

Green Area Factor (GAF) that has also been employed in the current and future comprehensive plan of the city of Tartu.

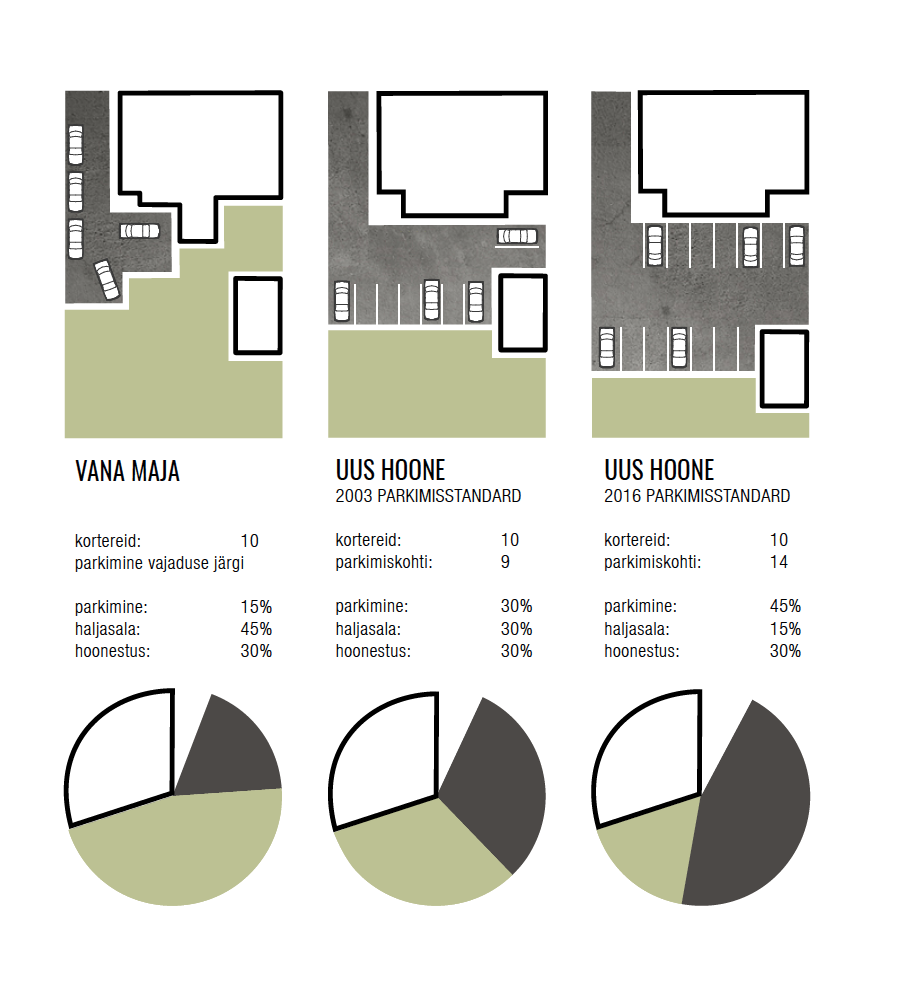

The balance between construction and green areas is currently established by the parking norms set by the city street standard and the living unit per plot area ratio. The latter sets the limits for building volume, more specifically the ratio of the number of apartments and the plot size. The parking norm relates the size of the apartment with the number of parking spaces. Thus, the more numerous and larger the flats, the larger the parking area, in other words, fewer green areas and more pavement. The norms are actually only indicative, however, they tend to be taken as the minimum obligation as the common mindset seems to prefer apartments with unlimited parking possibilities. The above ratio with the additional clause prescribing that the plot must include proportionally more green areas than paved surfaces set limits to the constructional ambitions prohibiting further paved areas. The given values vary by region but the underlying idea remains the same: the construction on the plot must retain green areas to a designated proportion. There may be lofty development aspirations, however, the maximum number of apartments is defined by the index.

The currently valid rates help to establish the basic requirements for a good living environment without interfering in its essential quality. Lawns, swings and hedges do not automatically add up as a high-quality green environment, even if the necessary indicators balance out as required. The total surface area is often presented as fragmented pieces that are too small to function as a comprehensive whole. A developer, project manager or housing association with a sense of mission understand the true value of the investments in outdoor areas, however, the cost of greenery is still often considered ‘impossible’ or ‘excessive’.

The calculation of GAF has been taken over from Helsinki. In 2018, a research was conducted on the possibility of using the method in Jaamamõisa district in Tartu.2 The primary aim of determining the Green Area Factor was to alleviate the negative impact of the construction and the extension of the hard surface areas. The factor has a set point score and the planned construction work must not feature lower indicators.

The effect of climate change is mainly assessed in the water cycle context. Once the impact of vegetation is effective, the burden on the stormwater system is relieved and the threat of flooding reduced. Rainwater is an unexpectedly narrow focus, however, it does justify the means. Green area surfaces and their variations mitigate the threats accompanying downpours. The fact that it is only one of the services of a functioning ecosystem has no significance in terms of the big picture. If an effort is made to create diverse green spaces in the name of an effective water cycle, it is a win-win situation.

For the calculation of the green area factor, the plot size is compared to the green area free of construction. The so-called points are entered in the spreadsheet, assessing and mutually connecting 43 possible elements related to the green areas, and in addition to the foreseeable trees and bushes also natural rock outcrops, grasslands or ground cover, green roofs and walls, ditches and deadwood. The equation assesses the value of the existing as well as the planned green areas on the plot and draws up the total sum that is compared to the plot size and location and the planned construction.

However, we will actually have good results once top quality is upheld and demanded by as many stakeholders as possible. Full appreciation of green aspects still requires propaganda, education and preaching. Nevertheless, in appreciatively many institutions, groups and communities it has become a part of everyday work with numerous good examples and counting. In addition to constraining built-up areas, green values need to be backed up also in green areas, streets and industrial landscapes. Informed adjustment to climate change benefits not only our economy but primarily our health and years lived happily.

ANNA-LIISA UNT works a day job as a landscape architect at the public space department of Tartu City Government, at other times she dwells, studies, and works from her home office in Karlova district.

Comment

INDREK RANNIKU

Urban planner at the Spatial Design Department of Tartu City Government

The GAF assessment method is connected with a particular measure that primarily aims at filtering rainwater into unpaved surfaces with as rich vegetation as possible, however, achieving the goals is accompanied by numerous values starting from insects to aesthetics.

The formula is not ready yet for public use as we still need to consider some issues. We wish to avoid the threat of it becoming merely a tool for developers allowing them to tune up poor indicators by installing a few nest boxes. With the work commissioned in 2018 (Eesti Veeprojekt OÜ and AB Artes Terrae OÜ), we adjusted the wording of the aims and tools, and if the current comprehensive plan includes a very general description of the GAF method, then the new comprehensive plan will have the prescribed minimum point score that must be exceeded. At the same time, there are also all the current recommendations and requirements for keeping the green balance, that is, the living unit per plot area ratio and parking norms together with the green area requirements in the street as a separate section.

In general, however, everybody understands the importance of greenery in a city. In my childhood in the Old Town of Tartu, we used to play up in the trees and down in the mud. And all of a sudden, there was no longer a single blade of grass left in those courtyards. Thus, keeping plots green is very important to me. It is now gradually starting to come back but there is still a long way to go.

These self-evident principles of green zones – lawns alone are insufficient, shades provided by trees prevent overheating, rich plant communities offer habitats etc – are currently being presented as a new ideology that mostly sounds either very naïve or very radical. Those whose activities or way of thinking is in conflict with it instantly feel defiant or superior. But trains always take their time.

HEADER photo by Mana Kaasik

PUBLISHED: Maja 105 (summer 2021) with main topic Landscape Architecture!

1 Grišakov, Kristi. Elupõhiste andmete kasutamine linnaplaneerimises. – Maja, talv (103) 2021

2 Jaamamõisa linnaosa keskkonnasäästliku planeerimislahenduse ja selle alusel sademevee säästliku käitlemise üldiste põhimõtete väljatöötamine Tartu linnale. OÜ Eesti Veeprojekt, AB Artes Terrae OÜ, 2018. www.tartu.ee/sites/default/files/research_import/2018-05/1769DP3_Jaamam%C3%B5isa.pdf