Questions by Sille Pihlak

Now, as the process of the rough diamond becoming an alluring (architectural) gem is complete, it is time to explore the fine cuts made to achieve it. We discuss the project through three generic terms: vocabulary – defining the key terms for the building, urban – contextualising it in micro- and macro-scales, and internal – from the interior ambitions to domestic relationships.

VOCABULARY

You often use the phrase Architecture archeology in your lectures. Is that what a museum is for you, or how would you define it? Furthermore, what does the term national museum mean for your office?

Per definition, the term museum originates from the word Mouseion, a temple dedicated to the muses, the divinities of arts in Greek mythology. The evolution of museums is also linked to the relationship humans establish to material culture, to the perception and significance of artifacts. Throughout history, museums gained various forms linked to the act of collecting, swaying between religious places (churches as places for the patronage and display of arts) to secular cabinet of curiosities or ‘wonder rooms’.

Inheriting a distinctive architectural aura, ‘wonder rooms’ opened to the public, and museums became places dedicated to the collection, preservation and display items of artistic, cultural, or scientific significance, for the education of the public. The last century, with the rise of the capital economy, more than a container of artifacts, we have also seen Museums become objects themselves, Architectural artifacts carrying the same name or brand in any country or city. Architecture became the tool to facilitate the setting of such status quo. While such museums allowed brands to leave their mark on any ad hoc territory, they also stigmatised the rapid digital transformation of our societies and questioned the relevance of art displayed through the growing focus on experiential, immersive artwork.

It is in this context that I arrive at questioning what can a museum be today? What role does it play in our societies? What position in our cities? How do they contribute to the manufacture of cultural capital?

I think museums as institutions have an important role to play in our cities, in the growing impoverishment of the public realm they act as engaging public places, able to operate as micro-cities, they have the capacity to be hybrid and multifunctional, functioning as social and cultural incubators of their context. In this sense, museums cannot be simple containers of objects, nor can they be allowed to be passive places for the consumption of culture, they are productive places of interaction, able to initiate action. They are also places where our senses shall be heightened and solicited.

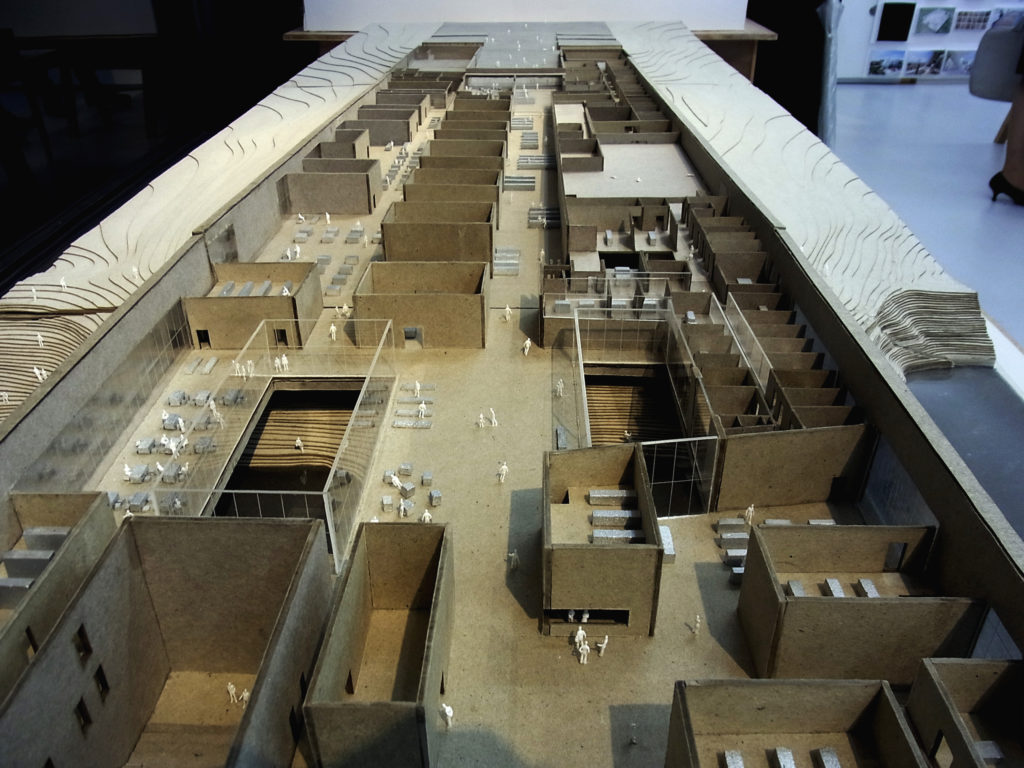

Today, it is in museums that we can question, discuss, play, talk, dwell, encounter, work, make, educate, disseminate… It is from this standpoint that I thought about the Estonian National Museum as an architecture that should belongs to its land, able to act upon the city’s scale and its social context. The building is designed as an urban generator, that can operate on the territorial scale, it links to a 1km long platform blurring the limit between what could be an urban gesture, an architectural project, or land art. It offers a new territory for cultural production and expands the program of the museum to house multiple educational and interactive ‘un-programmed’ spaces. The museum is thought to open new perspectives on the architectural as well as on the cultural level. It expresses an evolving contemporary world anchored in a specific territory. It simultaneously draws on the past, on the present, and on the future of Estonian culture.

You pointed out in your lecture in Tallinn, the idea of memory and place in time and space – could you elaborate on this?

I think Architecture has the magical capacity to reveal the aura, the genius loci – it is the protective and rejuvenating spirit of a place. A piece of architecture gains a stronger sense with the extent into which it is able to push the dialogue within its environment (social, cultural as much as physical or climatic/environmental). This is where the design process plays an important role, for me, every design is similar to an Archeological work that invites me to dig down, reveal traces, unveil stories, understand dynamics, in order to reconstruct new stories. A project does not happen ex-nihilo, and this is where a new edifice is able to withhold the memory of a place, of its people, of its geography; of its history. It is a new image, a new Architecture, that expresses through its being the infinity of time, the universality of space, the specificity of place, and the poetics of memory.

Please describe the several building stages of the Estonian National Museum, what you call them, and what are the categorisations based on?

When the museum was under construction it revealed different personalities, different postures, and established a transformation of the environment. It was fascinating to see the multiple facets of this Architecture revealed during construction. They become hidden, subliminal, when the building is completed. That is why I wanted to write the story of the construction, to depict every stage with a new state for the building.

At the beginning it was about “Constructing the Future”, as the piling of the building uncovered a mysterious and fictive archeology; “Building an environment” was possible with the first concrete skeleton of the museum; here we could see the large openings framing the poetic landscape, the museum was redefining the context and being redefined by it.

“L’homme qui marche” portrayed the workers moving along the 350 metres long building, the body scale inhabiting the spaces. In 2015, the building revealed its “monumentality”, we could see the cantilever of the entrance, the glazing covering the outer skin.

In 2016, “the city within one building” crystallised the maturity of the museum, the construction of all the inner volumes, these paralleled small family houses set under one roof. The museum was hence open for interaction.

If we talk more precisely about the workflow – how difficult is it to work with local architects, curators, museum keepers, was it different from your previous collaboration partners? Were there any cultural conflicts?

This building would not have been possible without the great support of local architects, HGA, PLSAB, KINO, and all the teams. A project of this scale and quality is impossible if the curators, the keepers, do not believe in the vision. Time was the only struggle throughout the process; the time to understand, the time to make, the time to build.

URBAN

It was positively surprising to understand the dual scale urban gestures, the small and the large – in one way the family houses repeating inside as white boxes, and then the overall landing/takeoff gesture. All those conceptual moves happen in the building, keeping the surrounding landscape rather minimal…

The position of the Estonian National Museum in the modest city of Tartu is rather surprising and impressive. I cannot imagine this building in any other possible context, any other site than the site of Raadi, as it draws on the history of the whole institution; the building is rather an impressive structure in terms of scale and size considering the small city of Tartu; The museum hence reinforces its role as a micro-city. The functions of the museum are articulated within volumes articulating a generous open space.

Furthermore the existing landscape of Raadi is very special, and historically fascinating in the contradiction it incorporates. It is a former military site, yet it has the poetics of nature that took over its history, it is the place where the first Estonian museum was established, and mixes both history as well as an atemporal feel. It was essential to keep the spirit of this place, and to intervene as little as possible in its beautiful and wild landscape. Walkways are simply drawn within the surrounding, interacting with the design of the museum and inviting one to wander around as the building reveals multiple identities through the varying heights of its site. It is a bridge, a line, a surface, a vanishing triangle from its side…

I learned there was also a programmed roof – what would it have added to the museum and was it a hard to abandon?

The building is 350 km long, it takes off from the runway. It opens up its limit, the beginning is an end and the end a new beginning at this specific point of the museum (entrance B), in the original design we intended to make the whole roof of the building accessible. Reinforcing the blurring of the limits between the past that the runway represents, and the future-present that Eesti Maja triggers. Due to budgetary and technical reasons, the roof of the museum could not be made accessible to the public, but I think that does not take away from the experience of the building, as one feels on the roof when on the airfield.

The idea of nature coming into a building and cutting the monumentality – is it still apparent or did it get lost on the way?

It is the essence of the interior experience of the building. For me this is quite present and conserved. Once you enter the museum, one encounters a first courtyard where a stone timelessly sits. The building’s monumentality disintegrates simultaneously with the many views framing the outer landscape. These views define the voids occurring between the volumes, carvings that suspend one’s body between the functional spaces and the poetics of the Estonian landscape.

This experience is heightened on the part where the building becomes a bridge. Occupied by the restaurant, the library and an un-programmed multifunctional space, this area is suspended and completely embraced by the outside. Wide voids open into the lake that smoothly runs underneath our feet. At this point, many public functions converge and play with the outside. In addition to the visible functions opening into the outside, the enclosed ones such as the conference hall slopes down to frame the pond running beneath the building. Here the landscape gains a new dimension, a cinematographic one, capturing the spectator in front of a picturesque moving painting.

Into the exhibition, the relation with the outside is pursued through the few openings in the ceiling. The ceiling dramatically lowers, leading into a darker space, spilling the visitor into the large expanse of the airfield.

INTERNAL

The interior is the incubator of culture. How much of the exhibition space did you manage to curate? (I noticed that all the public, intuitive free space is talking about the overall concept, but as soon as you step into the main exhibition hall, the space changes. It gets messy and intense, dominated by objects).

The exhibition scenography was designed by 3+1 architects. We didn’t have a say on that, it clearly talks another language.

One of the strongest spatial experiences of the building is the exhibition hall. One feels the tension of history, of the roof moving slowly down into a new beginning, the new entrance. I think there should be a strong dialogue to orchestrate between the spatial quality of the museum and the objects, their sizes, their density.

I’d like the idea of showing the objects as butt naked as possible, with the least visible vitrines, discrete showcases. The collection of the museum is fascinating, every object has a long story to tell, and you need silence, space to hear that story.

How important is the relationship between the exhibition in relationship to the overall shape itself?

I would describe the central exhibition space, mainly the permanent exhibition, as the spine of the building. It is the skeleton that holds and justifies the length of the building – the distance between the past and the future.

HEADER photo by Tõnu Tunnel

PUBLISHED: Maja 89-90 (summer 2017) with main topic Changing