After the slow-burning and partly contestable success stories of Rotermann Quarter and Telliskivi Creative City, the eyes of Tallinners interested in urban design or just longing for a better urban space turned to Noblessner—the privately developed waterfront set to become one of the first chapters on the road to open the coastal areas of Tallinn to its citizens. Though far from complete, the lively quarter already offers a chance for a status report and an insight into the entrenchment of certain spatio-social tendencies in the Estonian real estate landscape.

Humankind is transforming the planet into a vast infrastructural project serving its economic system. Landscape architect Hannes Aava explores how this development is reflected in critical theory and discusses what must be done to prevent the metabolism of humankind from becoming a metastasis.

As a country that has experienced Europe’s biggest increase in real estate prices, we will soon face the question: how to avoid reaching the top in segregation and spatial inequality too? Hannes Aava explores.

Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, collectively known as the Baltics, are three small countries that most of the world finds pretty much indistinguishable. As a geopolitical term, ‘the Baltics’ took root only in the 20th century. The more distant past and cultural history of the three countries differ on several levels.

Perhaps it is namely in defiance against externally imposed homogenising simplifications that we tend to turn to more distant places for inspiration and view local trends and tendencies as something confined only to national borders. However, anxious times encourage unity, urging us to discover and interpret our identities ourselves instead of letting others define us. In order to be carried and consolidated not only by fear, but also joy, pleasure, and curiosity we invite to discover commonalities and peculiarities of the Baltic countries!

Wide breadth, blurred boundaries, ambiguous endings and beginnings—the charm of the Baltic condition is not easy to grasp. But as Latvians say, per Reinis Salins: ‘Katram savs stūrītis’ (‘Everyone has their own corner’).

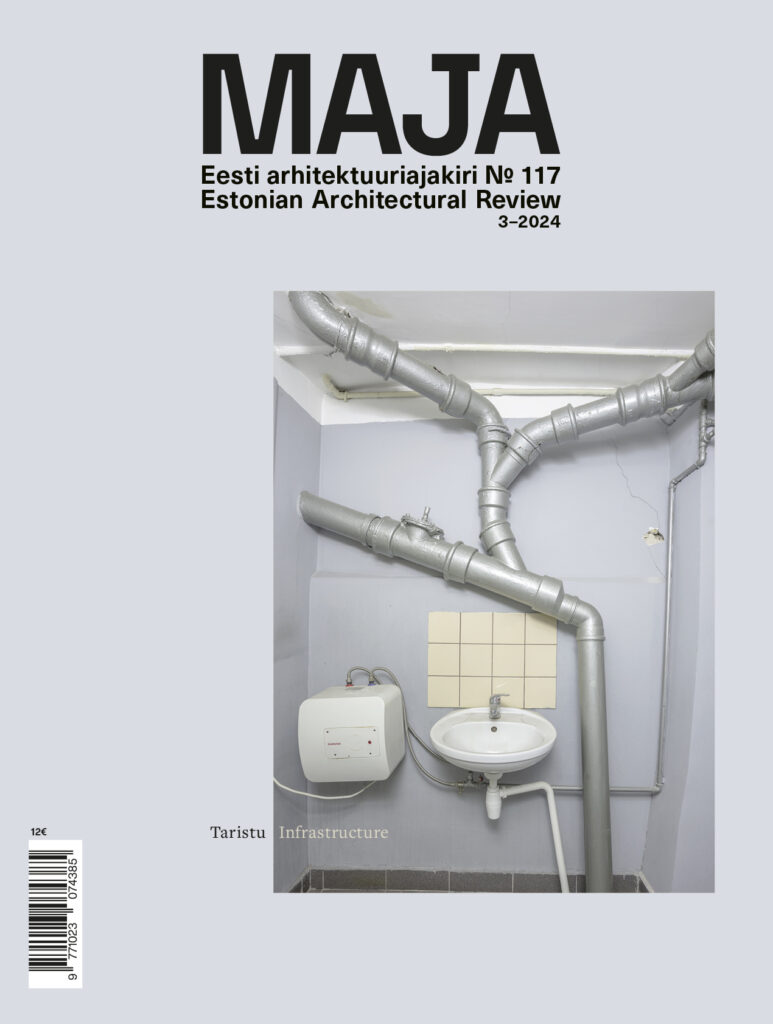

These days, to be is to be connected. Electricity, heat, road and street networks, internet connections, and water supply—it is as if all these intersecting and sometimes overlapping networks have become basic human rights. If these networks function well, our dependence on them goes unnoticed—we rarely take a moment to acknowledge the energy that travels across the sky, through underground and underwater pipelines, through wall cables, into millions of devices. On the other hand, when something disrupts the functioning of these networks, be it military aggression by a tyrannical neighbour, a sharp rise in prices, or catastrophic weather events, the political, economic, ethical, and often also spatial dimensions of these structures suddenly become apparent.

In order to compensate for the bureaucratic inflexibility and sluggishness that is burgeoning in spatial design, a new methodology has evolved that enables to operate in a more democratic, playful, experimental and cost-effective way.

Spatial design of a city is not a project with a clear beginning and end, but a continuous process, and a wickedly slow one at that.

The nominees and winners of this year’s Maja and Sirp Publication Award were selected by historian, cultural critic and assistant professor at the University of Southern California Aro Velmet, who highlighted the articles’ bold takes on broader social issues.

No more posts

ARCHITECTURE AWARDS