At 9 Rüütli Street among the small wooden buildings in the heritage area in Paide old town, there is a three-storey reinforced concrete Goliath—the old pharmacy warehouse. Due to its inappropriate scale in the environment, it has also been called an eyesore and disgrace to Paide. On a reinforced concrete frame, the extensive building with a full underground basement was initially constructed as a shelter and special-purpose warehouse. Currently, there is an appropriate institution operating on the ground floor—a reuse centre. The owner of the building, RRK Logistics Parks, has its reservations about the future value-in-use. They have considered reconstructing it as an apartment building but the plans have been stalled. Even getting rid of the building is tricky as the massive reinforced concrete structure renders its demolition by implosion complicated and costly. Although the initial use of the basement level as a shelter has become a topical issue again, a function must be found also for the upper floors. Fortunately, both the owner of the building and the local government are open to new ideas.

How should we define heritage in a paradoxical situation where both the building and its surroundings could be regarded as heritage objects? Our editorial board asked architects to muse on the future of the building.

Heritage repository in Paide

Roland Reemaa

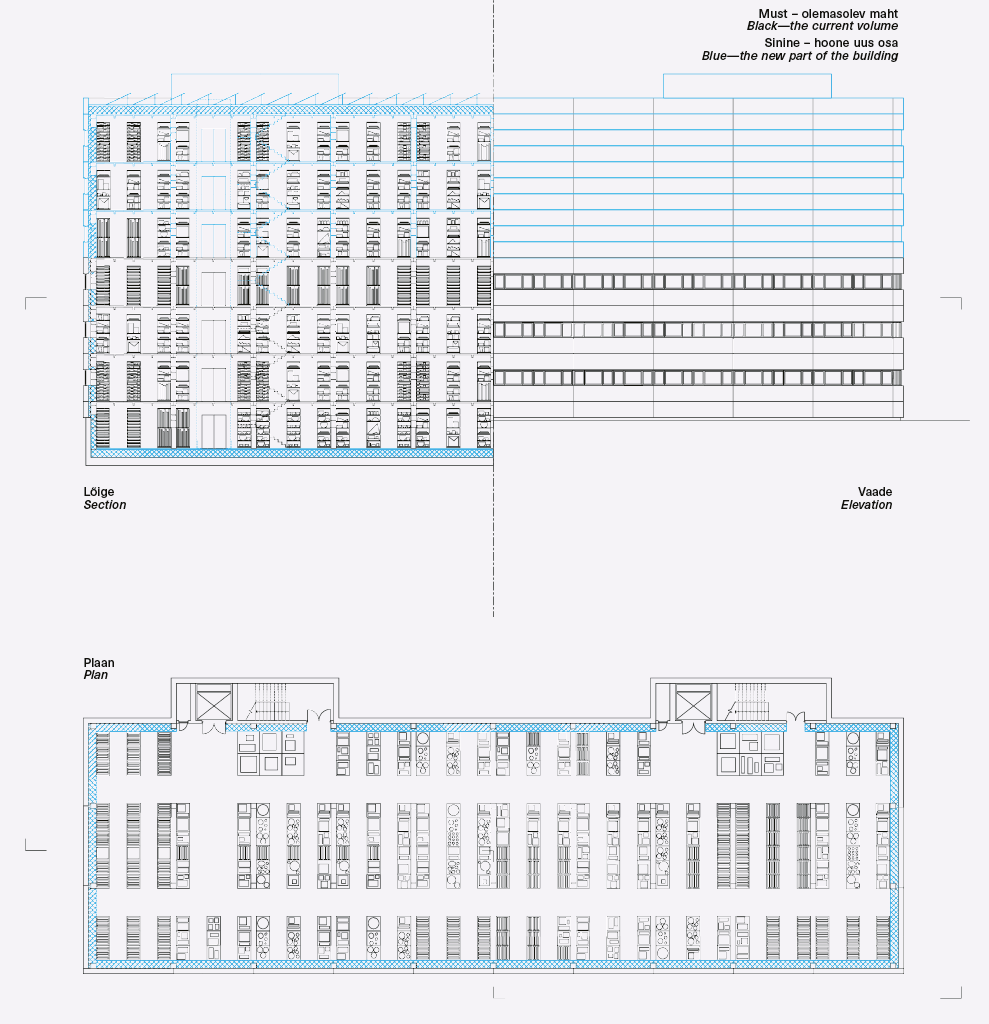

The blank walls of the former pharmacy warehouse and new heritage repository towering over Paide have formed a shelter for irreplaceable objects. Instead of condemning the size and aesthetics of the building as inappropriate in a small town, the project considers the current space and distinctiveness as an opportunity.

Much like the granary towers in Tartu or Zurich, also the new heritage building will be a landmark civilian object—something that we take pride in, maintain and exhibit with dignity. Located at the geographical heart of Estonia, the heritage repository is easily accessible from everywhere across the mainland. While so obviously ignoring the aims of the heritage protection area in Paide old town, such as the conservation of the wooden details, the reinforced concrete building paradoxically imposes the same values within itself. The given spatial heritages—the town and objects—are separated by the concrete shell. It appears that the building must be further expanded in height as well as in the thickness of its walls. Altogether three floors must be added to the present building to reach the repository’s necessary size of about 7,100 m2 that due to the heat capacity of the current and new material would restrict and reduce the fluctuation of room temperature and humidity and also provide the optimal indoor climate for storing heritage objects.

Material dreams, useless uses

Ulla Alla, Mari Möldre, Merilin Kaup, Margus Tammik

Three alternative present states emerge in the concrete building sprawling among small houses in the heart of Paide. These could be regarded as useless uses as it is difficult to implement them for the purpose of making money. The ‘profit’ and practice of the scenarios will appear in other spheres of life. Instead of striving for growth, our project is based on degrowth and shrinkage.

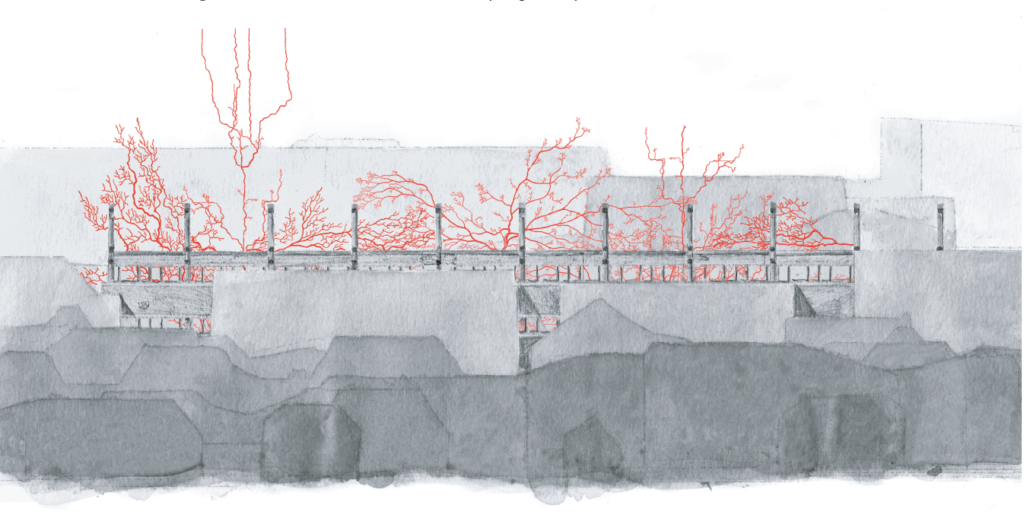

A thicket that we need

Giving the building a chance to grow roots and shed the roof

A refuge for rats, wanderers and others

Those who want to escape the watchful eye of practical people

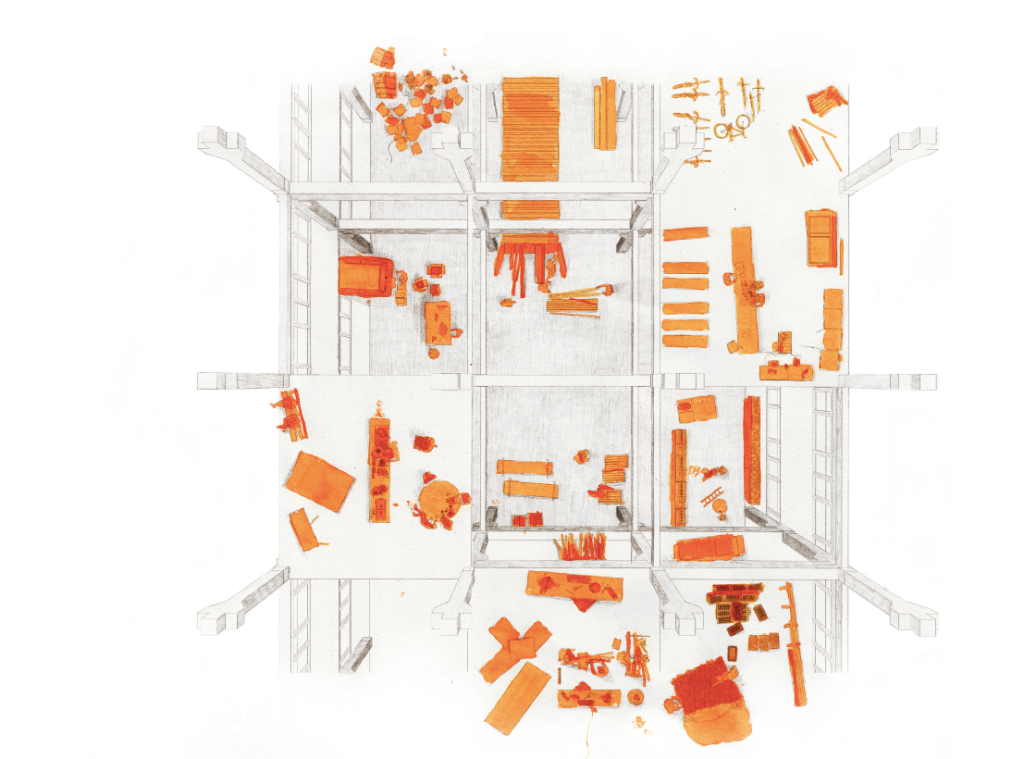

The house of everything

A shelter for abandoned things

Gathering, piling up and taking away

Switching on a homeless cooker, baking a cake and having a birthday party

Between piles, heaps and stacks

Freedom of things, freedom of space, freedom of action

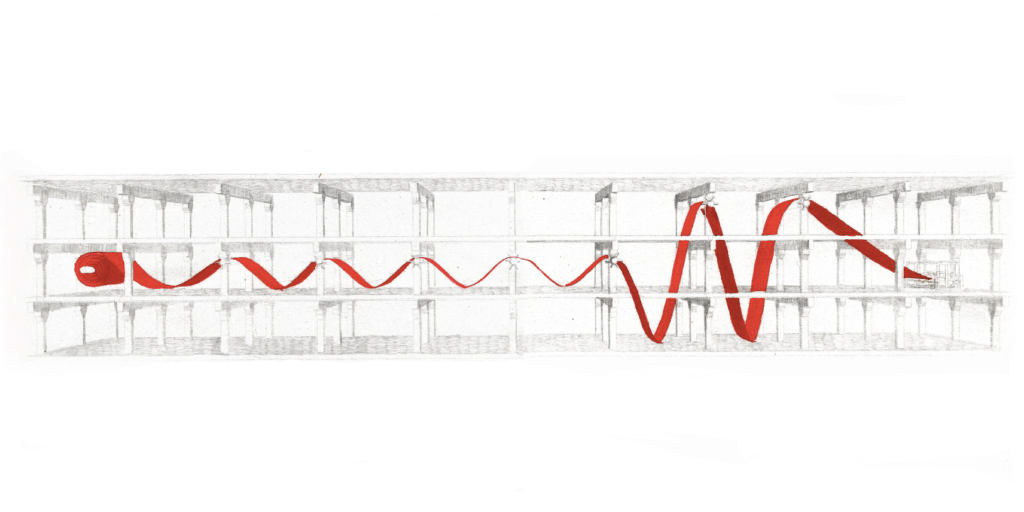

An endless carpet

Weaving, knitting, decorating together

Carrying on the tradition

Cardiogram of a small town

Our old rags at one end, those of the third generation at the other

Moths in the middle

Illustrations by Ulla Alla, Mari Möldre, Merilin Kaup, Margus Tammik

HEADER illustration by Ulla Alla, Mari Möldre, Merilin Kaup, Margus Tammik

PUBLISHED: Maja 109-110 (summer-autumn 2022) with main topic Built Heritage and Modern Times

1 See Tartu grain elevator (August Komendant, completed in 1941) or Swissmill in Zurich (Harder Haas Architects, completed in 2016).