The Urban Forum held on June 14th–15th was looking for the subtle balance between the activities of visitors and locals as well as the old and the innovative new.

Tallinn Old Town is a clearly defined urban space. Distinctly marked by defensive walls in the past, the historic merchant town is still a city within a city, and not for its physical city walls but primarily for its status as a UNESCO World Heritage site. With age, the dense urban fabric with its medieval structure has become an attraction which, in turn, in order to maintain its authenticity, has clearly also determined the possibilities for organically innovating and updating the urban space.

Keeping the Old Town as an attraction is quite an expensive habit in more than one respect. To start with, the restoration of historical buildings and maintaining heritage sites is more expensive as today only a small number of accomplished craftsmen can manage to make many of the restored parts or details, while building with novel materials and technologies is feasible for just about everyone. The technical installations of most buildings in the Old Town are outdated, and sometimes also the structures supporting the building need a complete overhaul as the centuries-old houses often do not measure up to contemporary living standards. The conservation of the Old Town will eventually also run counter to the inner need of every viable and active urban space to constantly renew and regenerate itself in time. This explains why many people still living in or already moving out of the Old Town find modern conveniences in the urban space so attractive. A contemporary city functions differently than allowed by a firmly established old town.

One of the key aims of contemporary urban development is to make things better than they were earlier, and that is why new architecture is not designed in medieval terms. This is also the reason why people tended to move from their flats in the Old Town with cold water as the only mod-con to modern pre-fab apartment buildings in Mustamäe equipped with baths and hot water from the tap. Coming back full circle, the Old Town lifestyle also includes numerous admirable features. However, it is a cause for major concern that the greatest question marks of the development trends of Tallinn that historically has radiated out of the Old Town lie precisely in the initial convergence point area. In a city district that is taken over by tourists, where motor vehicle traffic is highly uncomfortable and you live in constant fear of some potentially bursting pipe.

It is ironic that our protected and authentic Old Town is mostly affected by one of the manifestations of globalisation—mass tourism. People all over the world spend a lot of money to come here and admire the former ambience without having to turn into medieval people themselves. This gives rise to a particular cacophony in the urban space as the scenic medieval streets are marked by romping boozy bachelors, wealthy pensioners or lifestyle influencers equipped with selfie sticks as well as other weirdos stepping off cheap flights or cruise ships to roam through the city behind a tour guide and snap up souvenirs of dubious origin. There are no craftsmen and merchants clad in medieval outfits living in the Old Town, however, they are prominently visible in the streetscape inviting tourists to buy knitwear or try out a tasty bear roast. On the one hand, the invasion of foreign tourists has elevated Tallinn to the heights next to Venice, Bruges and other old towns, then again, it has also made it surrender to the pressures of modern tourism and thus mutated the daily life led in the city. The Old Town has not yet been declared an open-air museum, there are still some traces of real life hidden beneath the surface.

The suppressed and shrivelled state of the local culture in the Old Town oriented to mass tourism became painfully evident during the COVID pandemic when the tourist flow halted almost overnight. The streets were left empty and all the lights turned off. There was practically no life. In the previous years, life in the Old Town had been increasingly tourism-oriented and similarly, the current post-pandemic era with the monopoly of McDonald’s shaken only by Viru Kebab settling in the medieval gatehouse and Burger King sprawling across the road is tearing the local people’s heart out. Something must be done to save the delicate living environment from the trampling feet of mass culture. Similarly, contemporary Tallinn needs to have its historical centre back, although the medieval town originally had little to do with native Estonians.

The Old Town Urban Forum organised at Von Krahl Theatre (that has wound up its activity in the Old Town by now) on June 14th–15th was searching for solutions how to develop and administer the Old Town so as to keep it as a diverse city centre and a functioning living environment instead of a city district marked by tourists and parties.

The main discussion topic of the participating architects, urban designers, local residents, business owners operating in the Old Town and representatives of other interest groups1 was how to connect the Old Town again and better with the contemporary city and lessen the priority development of tourism without having to ban tourism in the Old Town altogether. It is important to find the fine balance between the activities of the locals and the visitors as well as the valuable old and the innovative new.

The recommendations can be roughly divided into two: regulations, prohibitions and conditions for organising life in the Old Town and potential development trends by means of implemented projects and activities. Based on the presentations, the leaders of the working groups Triin Talk, Sille Pihlak, Villem Tomiste and Johan Tali formulated eight main goals that could be reflected in all future development documents regarding the Old Town and city centre area of Tallinn.

1. The activities in the public space in the Old Town are primarily meant for local residents, there is considerable freedom to operate as well as public space for use free of charge.

Public events (Christmas market, Old Town Days etc) and street trading should be organised in a way as to meet primarily the needs of local residents, not tourists. Instead of selling amber, there should be events and attractions for children, community fairs, farm food stalls, art events etc. The Town Hall Square should be used mainly as a venue for events, while the markets should be moved further away from the centre of the Old Town to the streets and bastion belt.

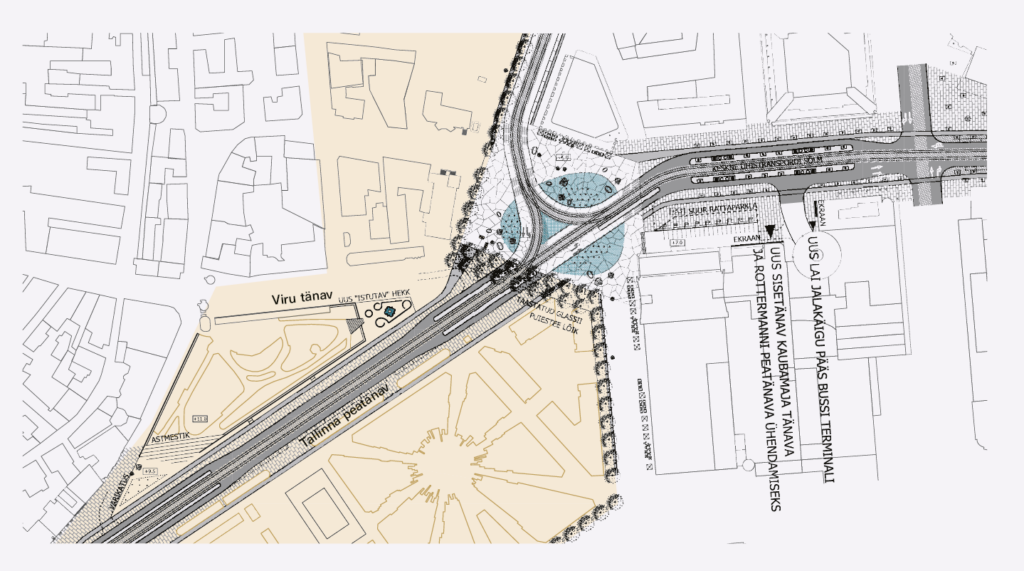

In order to bring more local life to public spaces, there should be more possibilities for sitting and spending time with no obligation to consume, for instance, more benches (also ones that could be folded to ensure peace in quiet hours) and community terraces (or contemporary versions of medieval porches with plant containers instead of café terraces). There should be no bureaucratic procedures required for organising temporary events in public spaces that do not harm the heritage objects (snowmen, art performances, small-scale events, unattached benches etc).

2. The use and interim use of buildings in the Old Town are curated.

Entrepreneurship in the Old Town tends to lean towards tourism industry as there are more tourists than local residents. The locally targeted use of spaces owned by the city and the state allows to keep the city centre functionally dense and diverse. One possible solution would be the establishment of a municipal company responsible for administering real estate in the Old Town and thus leading the value-based use of municipal property. Successful areas (Telliskivi, Noblessner) are characterised by curated entrepreneurship: selecting their tenants allows them to create their own identity and keep the different types of business in balance. For the given purpose, forcefully differentiated pricing is implemented with lower rent prices offered to companies who enrich the ambience and contribute to the local identity. One of the first tasks should be conducting an audit of the property in municipal and state ownership and making the political decision about the buildings that should be retained in public ownership as well as considering carefully in which cases the sale of property might be feasible instead. It is better to seek and allow interim and temporary uses for unused state and municipal property than keep the buildings empty.

3 There is more housing in the Old Town for economically diverse resident population.

High property prices tend to have a segregating effect, furthermore, the majority of residential premises in Tallinn Old Town are used for tourist accommodation thus further reducing the availability of housing. It is common in European countries that short-stay rental accommodation is licenced and restricted, with affordable municipal housing retained in urban centres to maintain diverse permanent population, for instance, by establishing rental houses or art residency and residential incubators that would bring more creative people into the area. The outskirts of the Old Town would also be a suitable site for a care home for the elderly.

4. The Old Town is accessible to all.

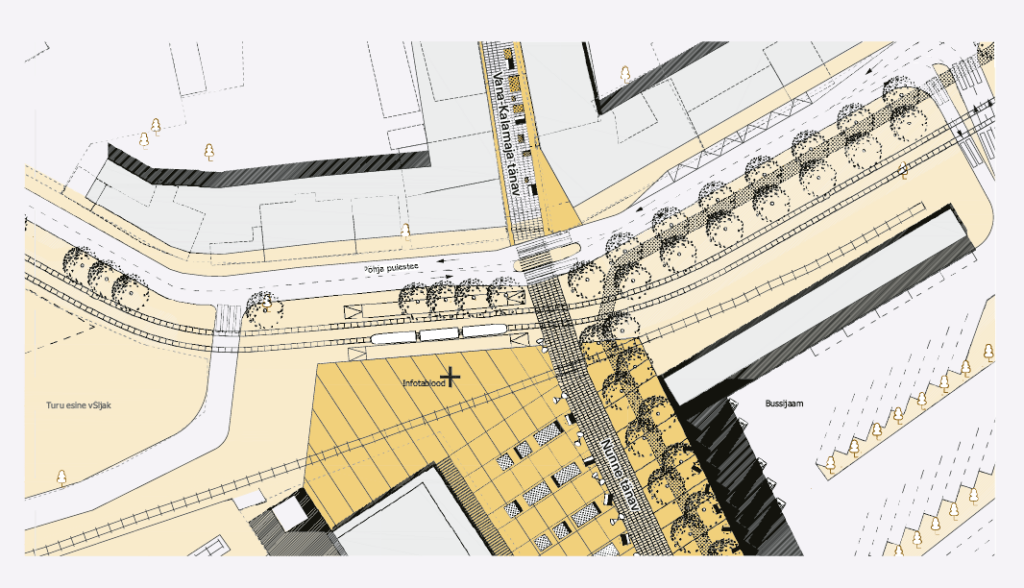

In order to make the Old Town a safe and pleasant living environment for people moving around with a pram or a wheelchair, the streets should be reconstructed with the sideways brought to the same level as the roadways. This will also lead to a more active use of basement rooms and a more accessible single-level street space. In order to reduce motorised traffic, gates could be installed licence-plate recognition cameras allowing only the residents’ cars and emergency vehicles to enter.

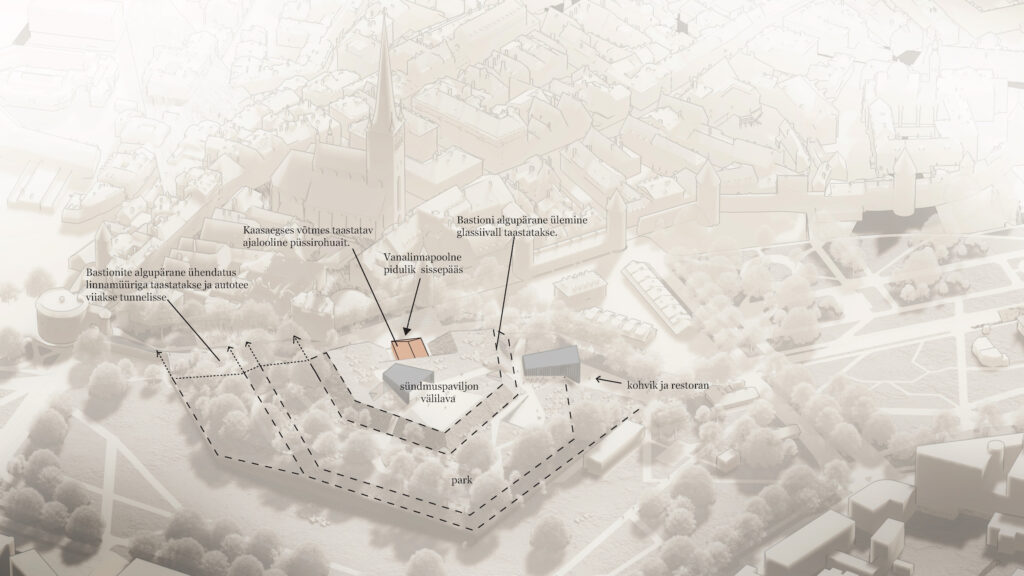

Establishing rental car parking areas around the Old Town is of primary importance in making the residents of the Old Town and the city centre prefer rental service to private cars. The parking lots around the medieval centre could offer discounts to local residents as well as customers of the restaurants and cultural institutions located in the Old Town. The main development potential of parking, waste management and logistics primarily lies underground in the bastion belt. The new underground constructions should be flexible allowing their functions to change over time, while the surface on the current ground level could be activated with various recreational activities.

5. Quiet hours in the Old Town are ensured by leading the nightlife elsewhere.

In order to ensure public order and quiet hours at night-time, the police and municipal police should patrol the city on foot rather than by car. It would also be useful to run an information campaign on window displays, sign a goodwill agreement with local businesses and even hire a night attendant helping to discipline the troublemakers. A long-term perspective should include leading night-time entertainment away from the Old Town as there are residential buildings in every street while the improvement of soundproofing is rendered almost impossible. There are far more suitable party venues in former industrial areas and similar districts where the buzz would not disturb the residents.

6. The Old Town is connected with the surrounding areas through the actively used bastion belt, thus forming an integrated spatial whole.

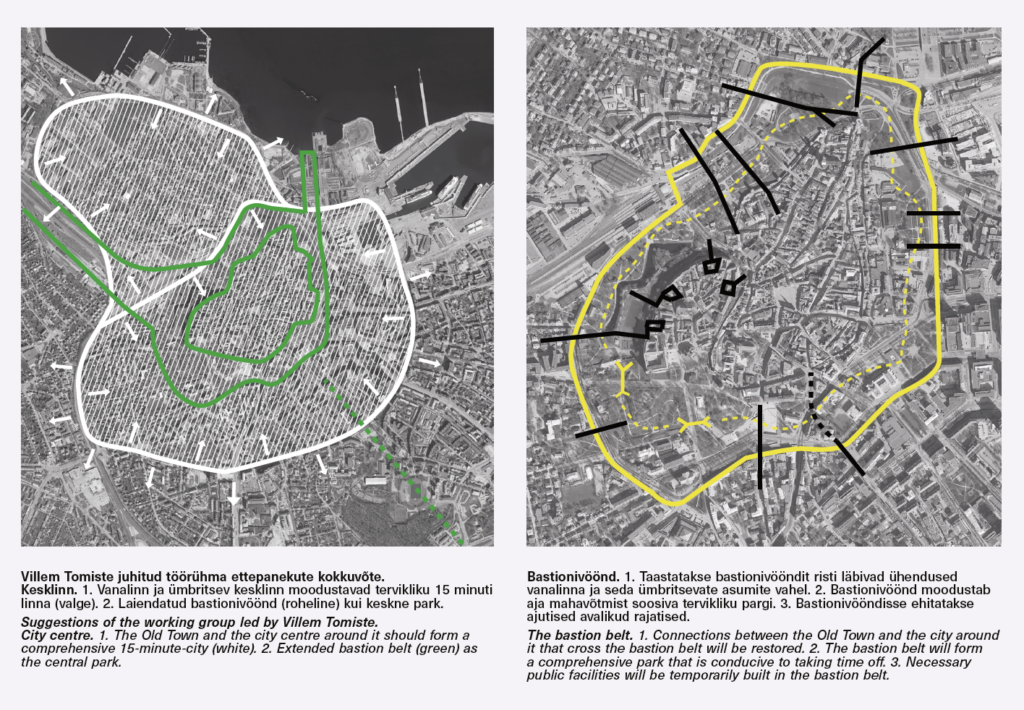

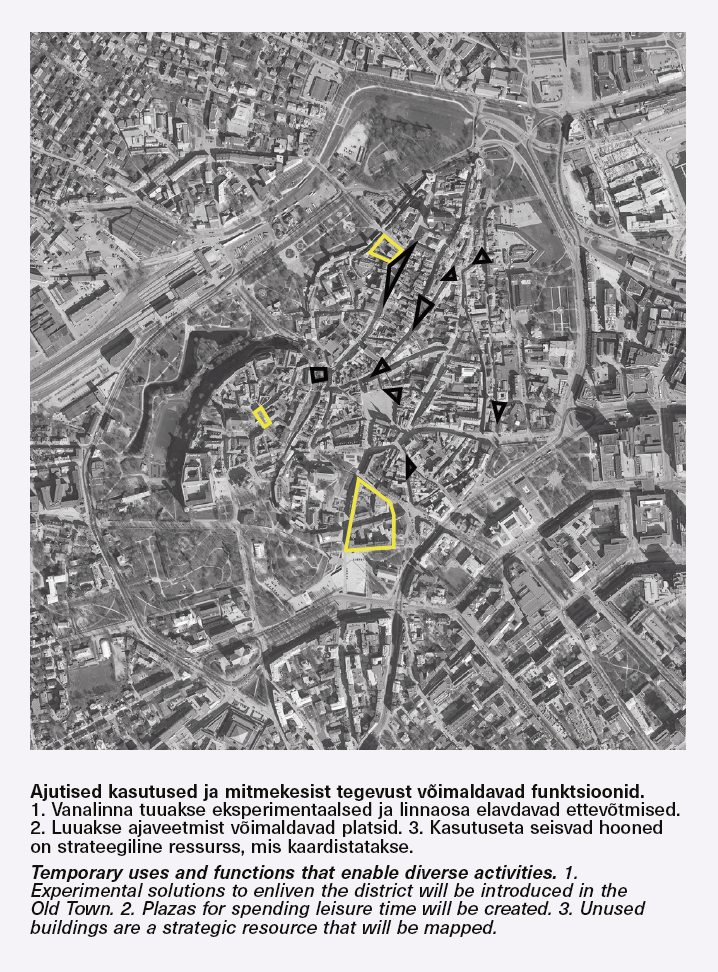

Connecting the Old Town with the surrounding urban areas is the best option for creating a dense and walkable 15-minute city in Tallinn.2 The bastion belt which currently tends to generate interruptions in the urban space could play a key role in this attempt allowing to create a spatially coherent small city. Pedestrians should be provided connecting routes to the surrounding areas, including steps down from all viewing platforms in Toompea and the extension of Pikk Street to the passenger port. In order to interlink the Old Town with all surrounding urban areas to form a central city space, there should be a tram roundabout at its outer perimeter with the entire area taken into more active use by means of particular spatial elements (for instance, trading areas, public toilets, sports fields, water taps, picnic tables, pavilions, stages, sledging slopes, skiing tracks, ice rinks, outdoor swimming pools, saunas, boat rentals). In the future, the bastion belt zone should be a place where something new takes place every day and all year round, including in the gloomy month of November. Just as the local parks have historically hosted various outdoor events, the green areas should be available for daily public events on a local or national scale in the future. Taking the souvenir market from the Town Hall Square to the bastion belt would allow to disperse tourism and avoid the overcrowding and intense focus on tourism on the central square.

7. Tourism is dispersed without overcrowding the Old Town.

Tourism must be directed away from the Old Town to allow also other city districts benefit from it and to avoid overcrowding the area and turning it into a strictly visitor-oriented zone during the tourist seasons. This could also be dispersed in time, for instance, by organising events enhancing cultural and sports tourism mainly off-season. It would not be reasonable to increase the capacity of cruise ship visits, instead, pursuant to relevant analyses, a respective cap on concurrent cruise ships should be agreed on. Visitors who leave the ship only to see the Old Town should be led there on foot along a footpath with as few disruptions as possible (that is, along the extension of Pikk Street to the port). In serving the cruise ship tourists, the public transport system should be preferred connecting the cruise ship harbour with the main gates to the Old Town. The stops and parking areas for tourist buses should be taken away from the centre, for instance, to Ahtri Street.

8. The Old Town has a representative and responsible entity.

In order to fulfil all the above aims and coordinate the activities, the position of an area curator should be established to lead the local development (including monitoring and encouraging the development plan implementation) and handle the local problems. The Old Town could be a pilot project to test the model and potentially extend it also to other urban areas in Tallinn. The curator should similarly involve the local community in the decision-making process, including residents, entrepreneurs as well as representatives of educational and cultural institutions.

* * *

The Old Town has evolved over a long period of time, so it is not possible to fix it all with a snap, instead, we should lead our life here systematically and to the full. The main message put forward at the urban forum was that the activities and rules of the city should focus on the common good (maintaining local life and culture in the Old Town) rather than financial profit (lining the city coffers, focusing on tourism). Having lived long in the Old Town and worked there in various roles, I can safely say that in my opinion the Old Town still needs to be (re-)discovered also by the local community.

JOHAN TALI is an architect at the architecture office Molumba, a doctoral student and lecturer at the Estonian Academy of Arts as well as the co-curator of the Open Lecture Series of the Department of Architecture.

HEADER: Small changes on Pikk Street. Kristel Akerman, Vello Leitham, 2022.

PUBLISHED: Maja 109-110 (summer-autumn 2022) with main topic Built Heritage and Modern Times

1

Working group 1: Johan Tali (leader of the working group, architect), Priit Pärtelpoeg (City Property Deparment, commercial premises in the Old Town), Liis Ojamäe (urban sociologist), Katrin Paadam (urban sociologist), Jaanus Juss (Telliskivi Creative Hub) , Toomas Paaver (architect), Vello Leitham (entrepreneur in the Old Town), Pille Kivihall (artist, Katariina Gild) , Anni Martin (Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communications, responsible for heritage issues), Jaak-Adam Loover (architect, Tallinn Strategy Centre).

Working group 2: Villem Tomiste (leader of the working group, architect), Kristiina Aasvee (architect), Siiri Valner (architect), Indrek Peil (architect), Siim Tanel Tõnisson (student of architecture), Priit Raud (Kanuti Gild SAAL), Kaire Tooming (National Heritage Board), Kristjan Hallik (ERSO), Peeter Erik Ots (Harjuoru), Kalle Komissarov (State Real Estate AS, architect), Kristel Akerman (conservationist).

Working group 3: Sille Pihlak (leader of the working group, resident, architect), Veiko Vahtrik (architect), Eva-Maria Aitsam (Tallinn Strategy Centre, Competence Centre for Spatial Planning), Peter Pääso (Ministry of Finance), Henri Kuningas (National Heritage Board), Kersti Nigesen (Vanalinna Hariduskolleegium), Eero Kotli (resident), Pertti Neero (State Real Estate AS), Kiur Lootus (resident), Andro Mänd (Estonian Association of Architects), Ville Jehe (local entrepreneur).

Working group 4: Triin Talk (leader of the working group, conservationist, researcher), Tõnis Savi (architect), Kersti Lootus (landscape architect), Oliver Alver (Urban Planning Department, architect), Evelin Tsirk (Tourism Department, Entrepreneurship Board, Tallinn Strategy Centre), Natalie Mets (the adviser for nightlife of Tallinn City Government), Katrin Roomet (Tallinn Guide Association), Roosi Aarma (local resident), Kerli Nõu (local resident), Rait Talvik (Estonian Centre for Architecture).

2

Siiri Vallner, Indrek Peil, ‘A Compact City Centre—Seven hypotheses with case studies for rediscovering Tallinn city centre’ in The City Unfinished: Urban Visions of Tallinn, ed. Pille Epner (Tallinn: EKA, 2021), 99–118.