Little was built following the re-establishment of Estonian independence in the early 1990s, however, the debates held and practices established largely came to set the foundations for the dominant issues in the architectural field in the past decades.

For Estonian architects, the first years of regained independence marked a period of comprehensive and complicated readjustments. In fact, the adaptation processes had actually begun a little earlier. Work conditions and opportunities for architects were influenced by the economic and political reforms accompanying the perestroika movement initiated by Mikhail Gorbachev in 1986, similarly the demand for sovereignty among other things over space spurred by national awakening as well as the sudden possibilities to communicate with the ‘free world’. All of a sudden, they needed to navigate not only in new intellectual currents but also among vastly expanded range of building materials. On top of that, there were new tools—in early 1990s, there was a gradual transition from hand drawings to computer-aided design, where available. With the land reform dragging on and investments rendered problematic, there was very little actual construction—the first new landmarks of the new era were completed only in the middle of the decade, for instance, Nissan Centre by Andres Siim and Hanno Kreis (1994) and the gallery café in Viru Street by Peep Jänes (1995). Actually, the most optimistic times in terms of design had been in the very last years of the Soviet period with several influential architecture competitions held and various designs for new commercial, office and public buildings commissioned. Due to the unstable political situation and legislative restrictions, most of them unfortunately remained only on paper. Nevertheless, this was the period shaping the ideas, expectations and practices that came to have a strong impact on the architectural practice and spatial design for the decades to follow. The processes of change are reflected in the unbuilt projects, architecture criticism and the opinions voiced by architects in the media, similarly events such as the Nordic-Baltic Architecture Triennial and also art projects ranging from visions of future cities to artistic performances.

A city of liberal society

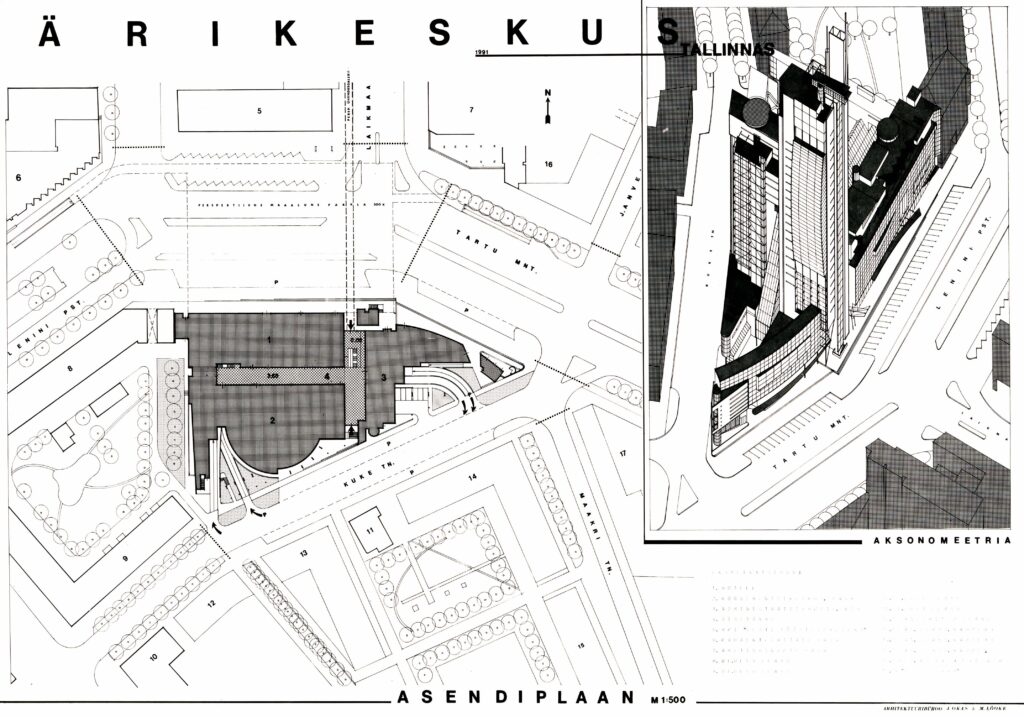

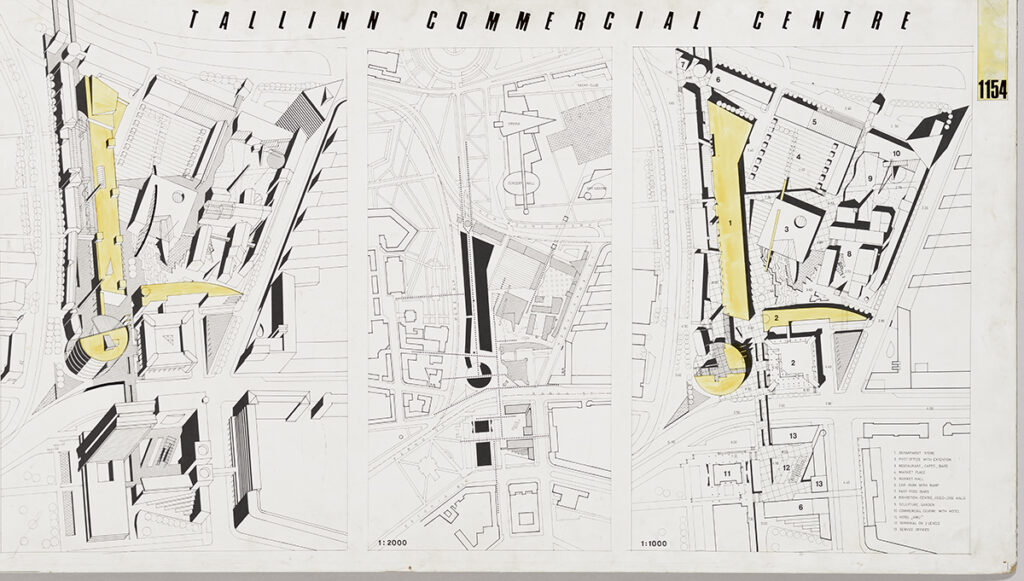

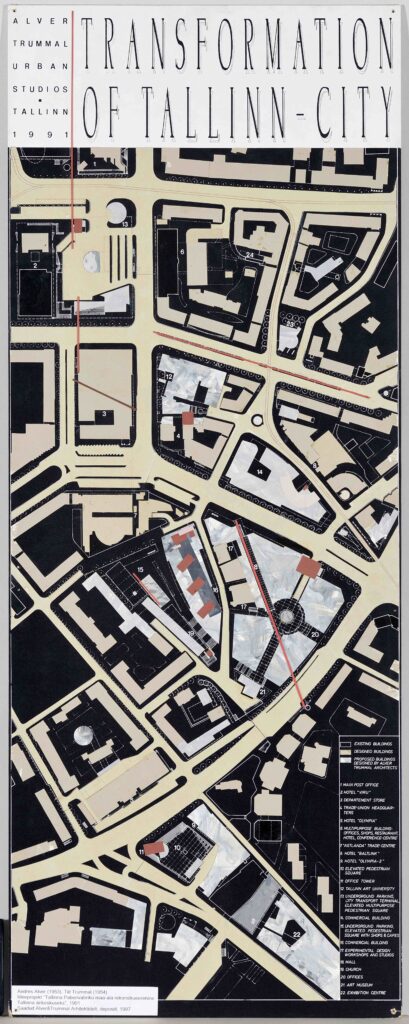

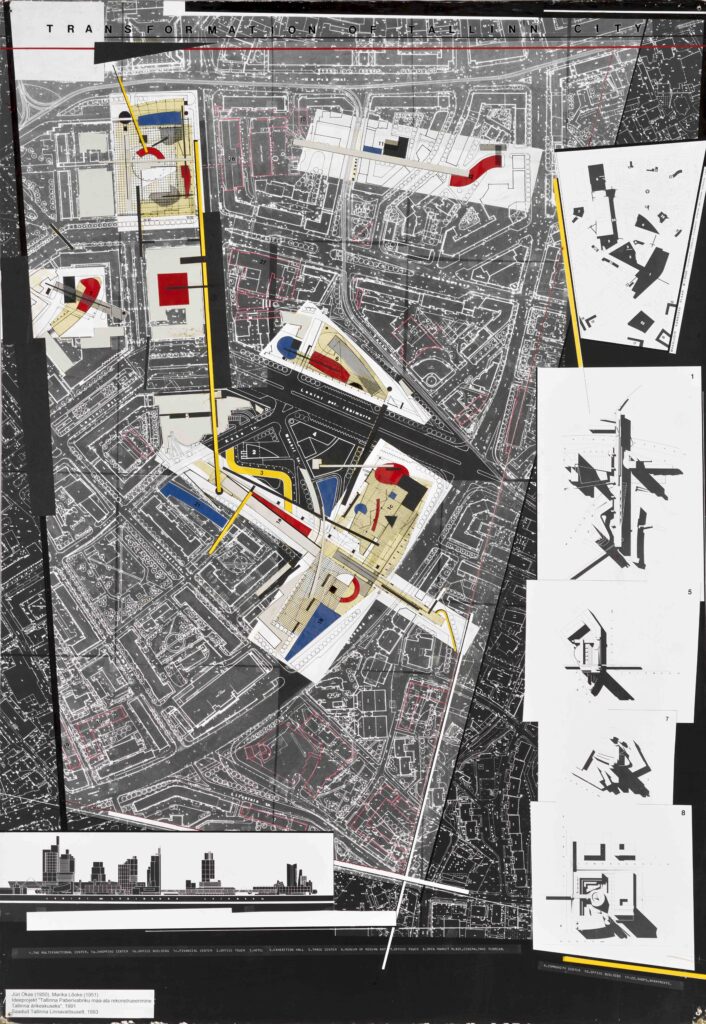

One of the signs of changing conditions was the architects’ rekindled interest in the urban scale. During the Soviet period, urban planning tended to be bureaucratic and ideological thus leading to a situation where individual buildings were considered as the architect’s real creative output. The competitions held in late 1980s seemed to reflect a shift in mentality. The competition entries of both the shopping centre in Mere Avenue (the current Rotermanni Quarter) and the area near Süda and Tatari Streets (both in 1989) included visions of dense, open and multifunctional spaces dominated by commercial, cultural, recreational and administrative buildings. The solutions ignored the Soviet norms and restrictions, thus, for instance, Emil Urbel and Ülo Peil boldly suggested that the new opera theatre should be located near the Admiralty Basin which, at the time, was a strictly restricted zone. Then again, urban design was not research-based or data-driven, as authors relied on their intuitive estimations and uninhibited visions of the appearance and functionalities of public spaces in a democratic society. So, it was no wonder that, inspired by the Western examples, the new public spaces were largely envisioned essentially commercial—they lacked the kind of utopian dimension featured in the late Soviet visions, as the new environments no longer strove for the complete transformation of human experience but for enjoyable, busy and affluent everyday life. Similar tendency is observable in the urban visions devised for the Milan International Architecture Exhibition in 1991 with Alver and Trummal, Okas and Lõoke as well as Künnapu and Padrik exploring the potential development of Tallinn city centre. The Milan projects also comprised the development proposals submitted to the city government at the time, including several high-rise projects such as Astlanda Business Centre, Olümpia 2 and Baltlink Hotel, with architects adding their ideas. In the vision of Alver-Trummal and Okas-Lõoke, the area between Viru Square and the paper factory in Maakri Street was to function as a single megastructural development with elevated walkways—the new keywords to describe the city centre were ‘polyfunctionality, horizontal and vertical multidimensionality, structure, density, communicability, centrality, convenience, scale and humanity’.1

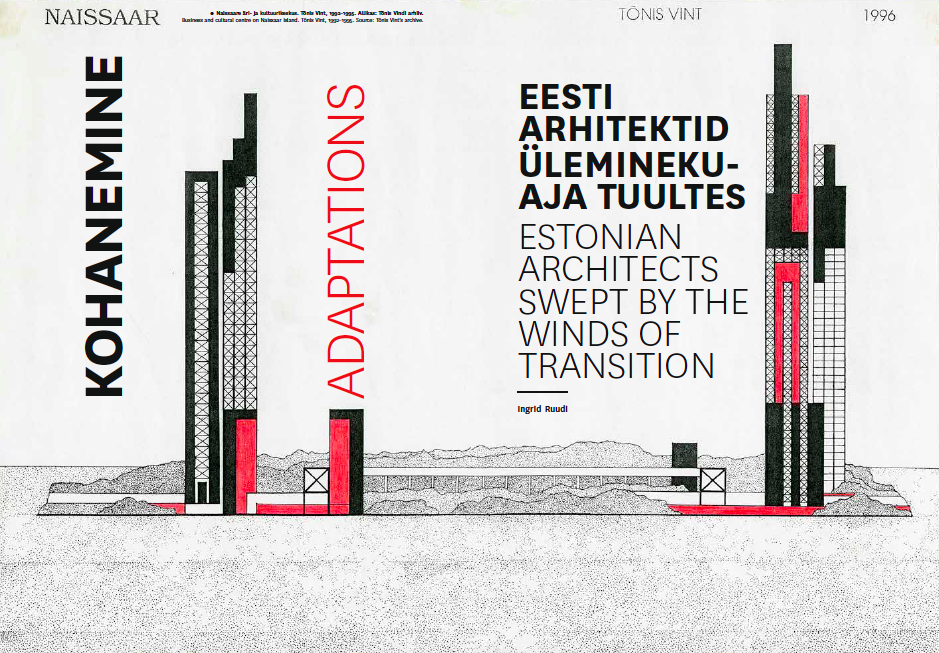

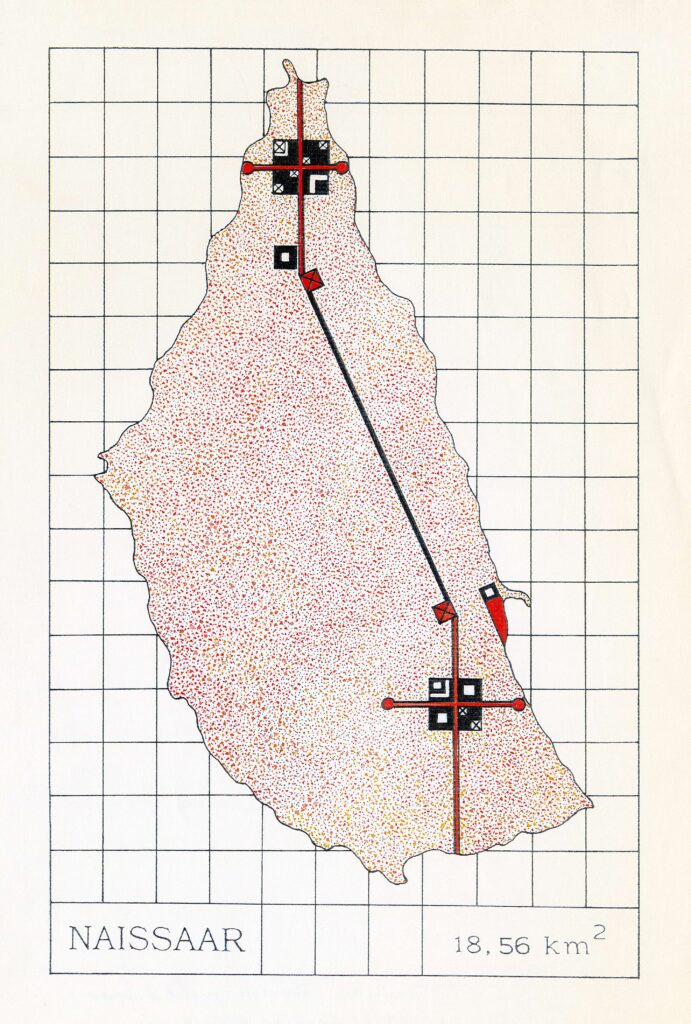

All the urban visions as well as perhaps the most fanciful of the proposals of the time—the new business and cultural centre on the island of Naissaar by Tõnis Vint—are visually highly impressive. The new urban space was presented as a set of strong visual markers suggesting the presence of a liberal, open and successful society—an image that life itself would gradually fill with content. Such strong imagological considerations are characteristic of all East-European transitional societies: they first ‘performed’ the desired lifestyle and environment they hoped to find a fast-track route to and skyscrapers provided the most effective means for such simulations. However, to the architects with a sense of perspective, high-rises soon lost their appeal—it was stated by Veljo Kaasik already in 1996 that it was not reasonable to yearn for high-rises in the face of an urgent need to deal with urban space at the street level.2

The changing image of the architect

The ways how a truly democratic urban planning should be organised and regulated were established in the course of the process. Various offers were accepted with an open mind, so, for instance, the detail planning of Naissaar in 1995 became a pilot project funded by the Ministry of Environment of Finland allowing to conduct an environmental impact assessment and to experiment with the principles of participatory planning. Nevertheless, architects tended to rely on expert knowledge with considerable scepticism about the involvement of citizens, reflected, for instance, in the prolonged controversies around the area near Süda and Tatari Streets.

One of the key issues arising in the adjustment to the new circumstances was the role and agency of the architect: what is the architect’s decision-making power and how can they have a say in the public? With the termination of large Soviet state planning organisations, architects with a more entrepreneurial mindset—the first ones including Toomas Rein; Jüri Okas and Marika Lõoke; Ado Eigi; Emil Urbel and Ülo Peil—established their own private practices already in 1989. However, it was considerably more difficult to maintain the former social authority as a small business owner, particularly in the early years of the new Estonian currency with the number of commissions decreasing dramatically and forcing several architects to admit that their professional work had become more like a hobby.3 However, they were firmly holding on to the image of the architect as an independent artist established by the Tallinn School in the previous decade, thus strongly influencing also the following generation from Andres Siim to Raoul Kurvitz.

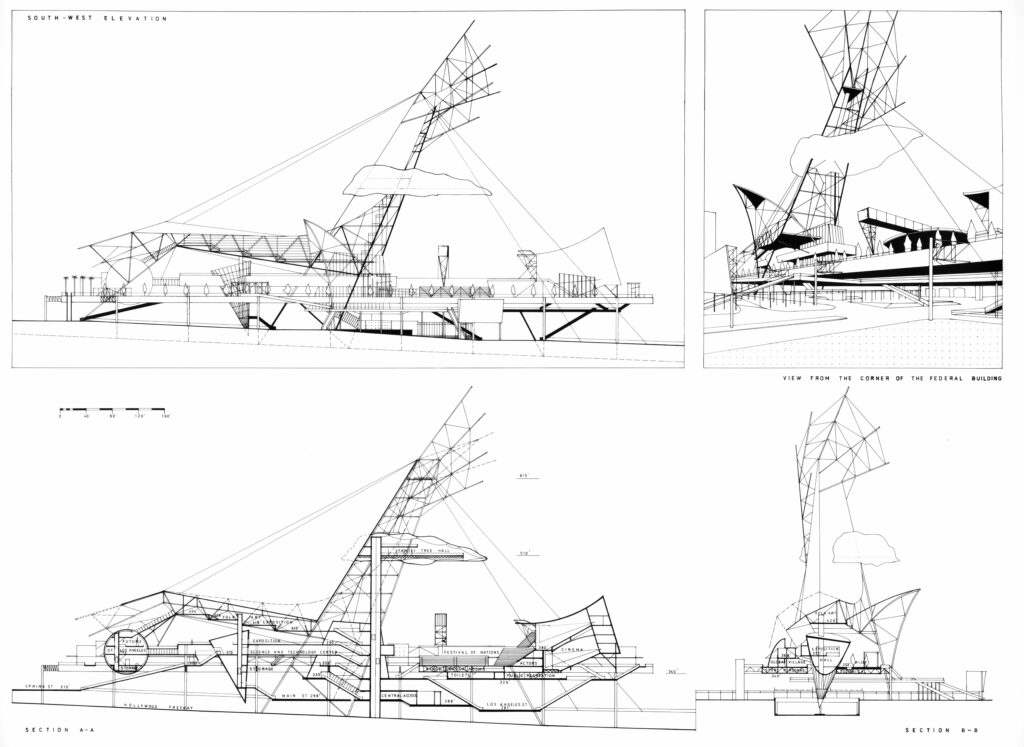

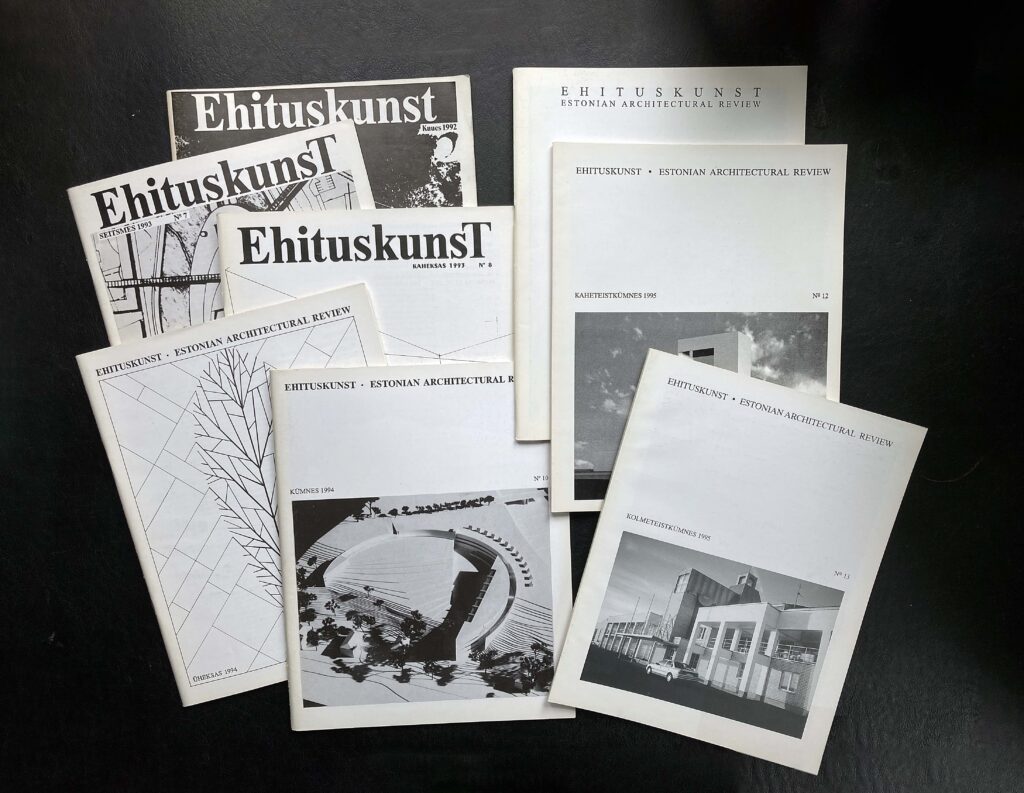

On the one hand, they wanted architectural issues to be heard in the media and in the public, while also striving for interdisciplinarity and dialogues with other professional fields. Thus, for instance, an entire television programme was dedicated to the entry by Künnapu, Padrik and Siim to the Los Angeles West Coast Gateway winning the second prize (1989); Tõnis Vint’s vision of Naissaar was first introduced in the weekly Eesti Ekspress followed by a similar special programme on national television; Rühm T (Group T) architects had their own special issue ‘Tsoon’ (‘The Zone’) in Eesti Ekspress and the series ‘Elustiilid’ (‘Lifestyles’) on national television. On the initiative of Irina Raud, also the first Nordic-Baltic Architecture Triennial was held in 1990—a conscious search for contacts with the architects of the so-called free world instead of the traditional framework of Soviet ‘friendship cities’, with preparations boldly starting already in 1988. The architecture review Ehituskunst was relaunched under the editorship of Leonhard Lapin in 1991.

All the given initiatives certainly contributed to the public acknowledgment of the diversity of the future prospects of spatial development. Then again, the harder it became to manage the rapid liberal capitalist developments and the more limited the architects’ power to lead the processes, the louder became also the calls for the preservation of ‘timeless’ and ‘spiritual’ values. With overlapping contributors and the creative teams mainly consisting of the representatives of the Tallinn School, the Architecture Triennial and Ehituskunst supported one another but at the same time also amplified each other’s weaknesses—the elitist attitude, leanings towards postmodernist phenomenology and the reluctance to tackle the more complex everyday architectural realities of the dirty laissez-faire capitalism of the young state. Likewise,4 the criticism requiring that architects should primarily stand up against commercialism did not acknowledge the potential dangers of the withdrawal to the ivory tower. In the given situation, some of the younger generation architects opted for a so-called silent position, and until the more forceful self-assertion of Andres Alver, Veljo Kaasik and Tiit Trummal in the middle and second half of the decade, it seemed that instead of self-reflection architects tended rely primarily on selected foreign authors as all the theoretical articles of Ehituskunst in 1990s were translations. Active relation to the West and accelerated catching-up lessons in an attempt to acquire the ideas of various theoreticians and to interpret them in a somewhat eclectic mix was characteristic of the transitional period not only in architecture but in culture at large. The situation in architecture was further complicated by the wishes or sometimes even demands of the developers and investors to include foreign (often Estonian émigré) architects that, on the one hand, allowed the local architects to learn from the Western know-how and, on the other hand, also provided the basis for criticism and a sense of superiority tinged with self-protectiveness.

The debates held and practises established in the course of the adaptation processes in the transitional period largely came to set the foundations for the dominant issues in the architectural field of the following decades. Forced to adapt to the rapid changes, architects built upon their best Soviet experience in an accelerated attempt to also acquire the necessary competence to cope with navigating among new clients, legislative framework, norms, materials and technologies. Their way of combining the experience and conditions stemming from vastly different contexts features positive open-mindedness and experimentation as well as controversies and failures. As typical of architecture as a slow discipline, the experience gained in the interregnum era came to have a true spatial effect only in the second half of the 1990s and to some extent to this day.

INGRID RUUDI is an architecture historian, critic and curator, a researcher at the Institute of Art History and Visual Culture of the Estonian Academy of Arts.

PUBLISHED: Maja 105 (autumn 2021) with main topic Spatial Revolutions

HEADER: Business and cultural centre on Naissaar island. Tõnis Vint, 1992-1995. Source: Tõnis Vint’s archive.

1 Jüri Okas, Marika Lõoke, „Ärikeskus Tallinna. Projekt 1991. a,“ Ehituskunst, 1992, nr 6, lk 43.

2 Veljo Kaasik, „Tallinna tornid ja Tartu city,“ Äripäev, 15.05.1996.

3 Nils Niitra, „Arhitektitöö võib olla ka hobi,“ Hommikuleht, 26.07.1993.

4 Mart Kalm, „Mis on saanud arhitektuurist?“ Eesti Ekspress, 21.05.1993.