INTERIOR

The aging population requires nothing less than a radical retooling of the territory, with architects and urban planners at the forefront of this transformation.

When I heard the news that there is now a lift in St. Nicholas’ (Niguliste) Church, I immediately thought of the famous Santa Justa Lift in Lisbon, designed by Raoul Mesnier du Ponsard, a student of Gustave Eiffel. On second thought, the type of lift in St. Nicholas’ is a bit different, of course, for the Santa Justa Lift connects two levels of a city built on seven hills while also functioning as a viewing platform and tourist attraction. Something similar to the latter was planned in Tallinn for the area between the so-called Roe Deer Park on Nunne Street and Toompea viewing platform by architect Herbert Johanson in 1935. Likewise, there were attempts—already in the 1920s, then in the 1950s, and for the third time in the 1990s—to draw up a lift (more specifically, a chair lift) for the Patkuli stairway zone. And yet, still no chair lift!

Mustjala care home and day centre was meant to be a pilot project for a standard design in Saaremaa. There is a shortage of care home places and the same kind of building was planned right away for Leisi too. While initially it was feared that life in such a care home would be too expensive, today we see that monthly bills for the residents do not exceed 300 euros.

The term ‘accessibility’ marks everyone’s involvement in the living and informational environment, regardless of their age or health, by ensuring equal opportunities for everyone’s participation in the society. The topic is increasingly discussed both on the national and municipal level, and work to improve accessibility is also ongoing in cultural institutions, including museums, which this article will be focusing on.

n Kärdla School in Hiiumaa, designed by Arhitekt Must, outdoor recess is not some laborious ideological effort, but simply an ordinary and natural idea, writes Kadri Klementi.

The Danish architect Mette Johanne Hübschmann analyses the domestic interiors of similarly speculative housing development from a feminist standpoint.

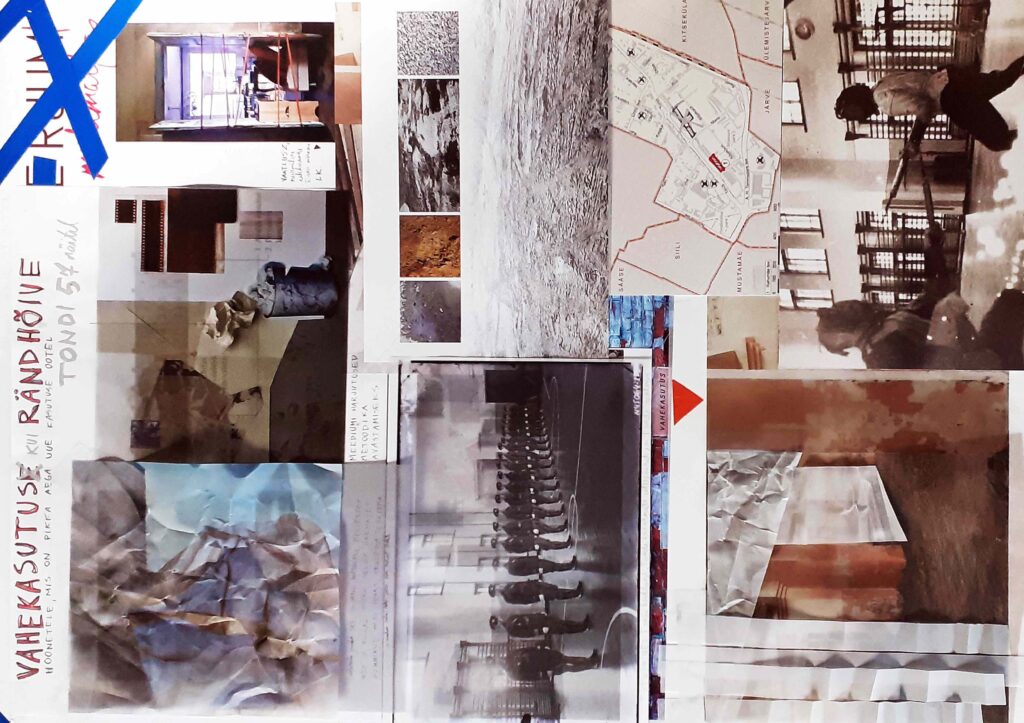

How can we explore the authenticity of interior space? Semele Kari moves to a barrack at Tondi and describes a pop-up interior architecture office inhabiting the desolate spaces as a methodology with the aim of finding the most suitable upgrade for them.

A building with a strong character is easy to hate. Or to love. Take, for example, Tallinn City Hall—few are indifferent to it. Many see the City Hall as an ingenious artificial landscape and urban stage, while others consider it a relict of the Soviet occupation that is unfit for a free Estonia, just like the Sakala Centre that was demolished in 2007. There are many other lesser or better known buildings from the Soviet period that are architecturally ambitious, but unacceptable to many for aesthetic or ideological reasons.

The new terminal is not just a building, it is above all an urban act, showing the way to and perhaps even anticipating the integration of the harbour and the entire seafront area.

A TV show called Restaurant 0 recently aired on Estonian Television, which focused on an experiment conceived by the Põhjaka chefs Ott Tomik and Märt Metsallik to open a conceptual restaurant in Viljandi within a single week. A question was raised on how it is possible to live sustainably and peacefully in a time when ecological catastrophe is imminent. Is it possible to establish a restaurant on zero budget and with zero footprint? The chosen location was an idle, rather deserted-looking 18th-century building in Viljandi. Studio kuidas.works was summoned to devise a spatial solution for the project.

Postitused otsas