MEDIATION

In the last few years, several public buildings with unexpected combinations of functions have been built in Estonia due to practical reasons, and soon, a series of state houses combining a kaleidoscopic array of institutions in smaller towns will follow. How do these public buildings reflect our present times, and how should they?

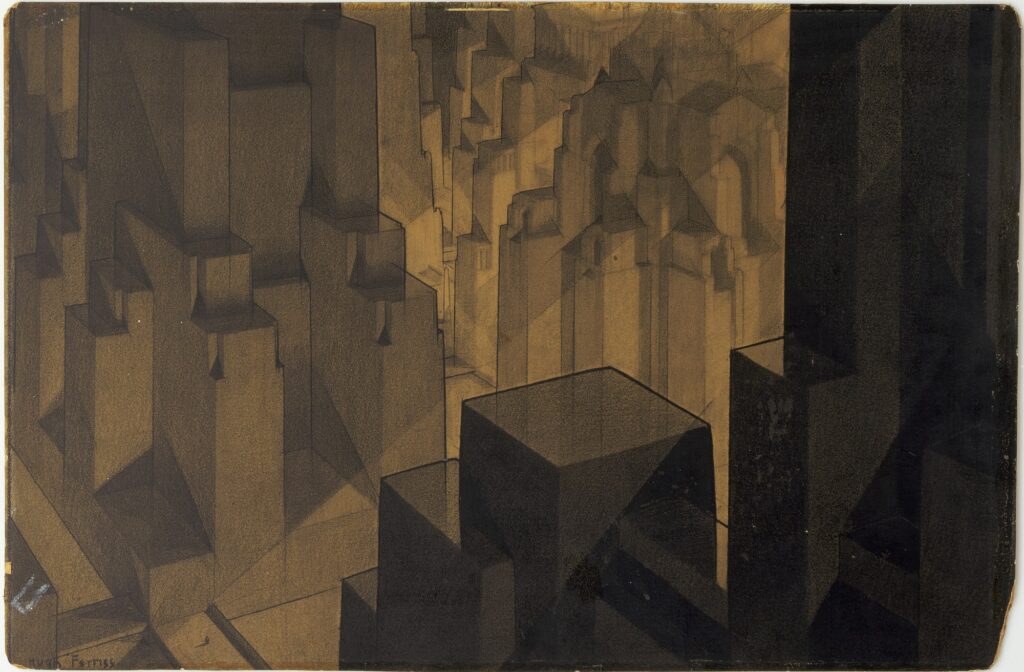

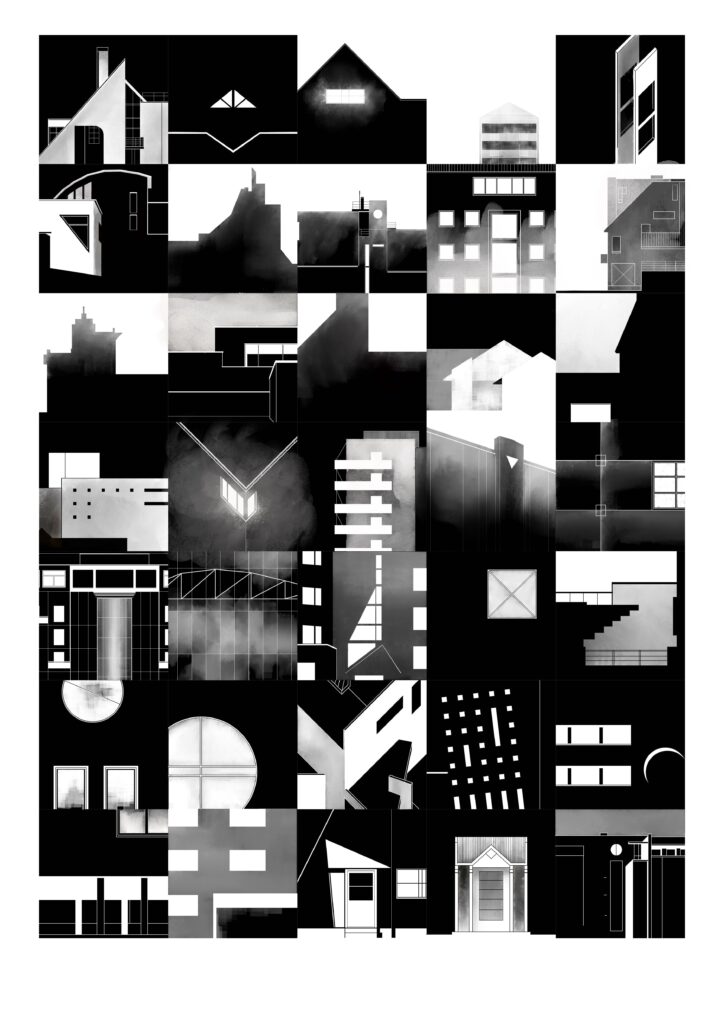

Graphic essay by Paco Ulman.

The way nature wills its way into every nook and cranny, even to places where it is unwanted, creates a feeling that freedom, free space, and free will still exist in the world. Burgeoning envelops small moments of pleasure, reverie, and rest on what would otherwise be a routine course from one point to the next.

Kõigepealt tuleb arutleda selle üle, mida saab üldse tühermaaks pidada. Kindel on see, et tühermaa on linnalooduse osa, kus inimese mõju on väga selgelt näha ja tunda. Võiks ehk isegi öelda, et tühermaa on inimtekkeline. Seal võib kohata varemeid, lagunenud taristut, ehitusjäätmeid ja muud. Kui püüame sõnastada definitsiooni, siis saame öelda, et tühermaa on inimese kasutatud ala, mis on seisnud aastaid kasutuseta ja mille loodus on aastatega üle võtnud. Kindlat piiri, mis on tühermaa, mis mitte, on siiski üsna raske tõmmata. Tallinna Ülikoolis oleme põhjalikumalt uurinud Lasnamäe tühermaid ja järgnevad suuremad üldistused teen just nende põhjal.

Answers by Roland Reemaa, Urmo Mets, Juhan Kangilaski, Andra Aaleo and Keiti Kljavin.

Six educators and practitioners from all over the world who specialise in interior architecture joined me for a discussion about how they conceptualise the role of the interior architect in spatial design, what the challenges of the specialisation are and what kind of education would help meet those challenges.

Six educators and practitioners from all over the world who specialise in interior architecture joined me for a discussion about how they conceptualise the role of the interior architect in spatial design, what the challenges of the specialisation are and what kind of education would help meet those challenges.

Estonian Academy of Arts (EKA) master’s theses in interior architecture demonstrate an ability to raise serious global issues, and a polemical search for what interior architecture could contribute to their resolution.

In the past years we have seen the state’s increased interest in and expectations for interior design solutions as a conceptual whole. In order to discuss what we have achieved and where to proceed, the chairman of the management board of the Estonian Association of Interior Architects Pille Lausmäe-Lõoke was joined by the State Real Estate architect and former vice-president of the Estonian Association of Architects Kalle Komissarov and the spatial design project manager Kristiina Vasar.

Photo Essay: interior architect Aulo Padar 80.

Postitused otsas

ARCHITECTURE AWARDS