In the last few years, several public buildings with unexpected combinations of functions have been built in Estonia due to practical reasons, and soon, a series of state houses combining a kaleidoscopic array of institutions in smaller towns will follow. How do these public buildings reflect our present times, and how should they?

The invention of backbone

In 1978, Delirious New York by architect Rem Koolhaas was published.1 The book had considerable influence on architectural thinking. Even more striking than its main title is the phrase “retroactive manifesto” in its subtitle. Koolhaas attended Cornell University from 1972 to 1975, studying the construction boom of 1910s Manhattan. His research and method (although the latter term might be too narrow to do justice to Koolhaas’s extremely creative approach) contained a series of unusual elements. For instance, he collected his research materials by attending meetings of postcard collectors and studying caricatures published in early 20th-century newspapers. The key point, however, is not the nature of his sources, but Koolhaas’s attitude and purpose.

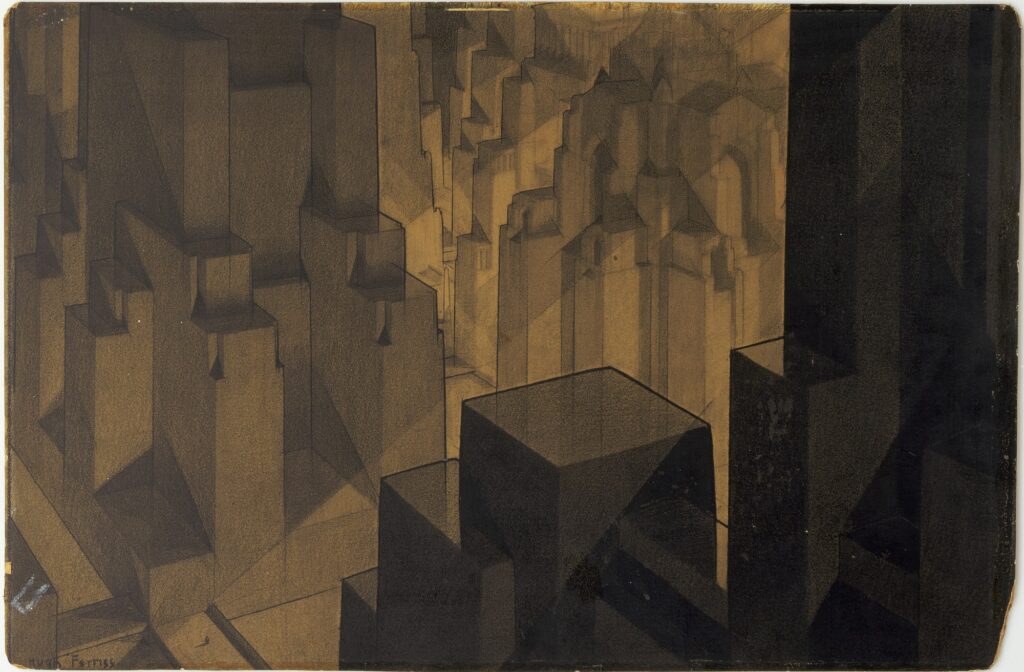

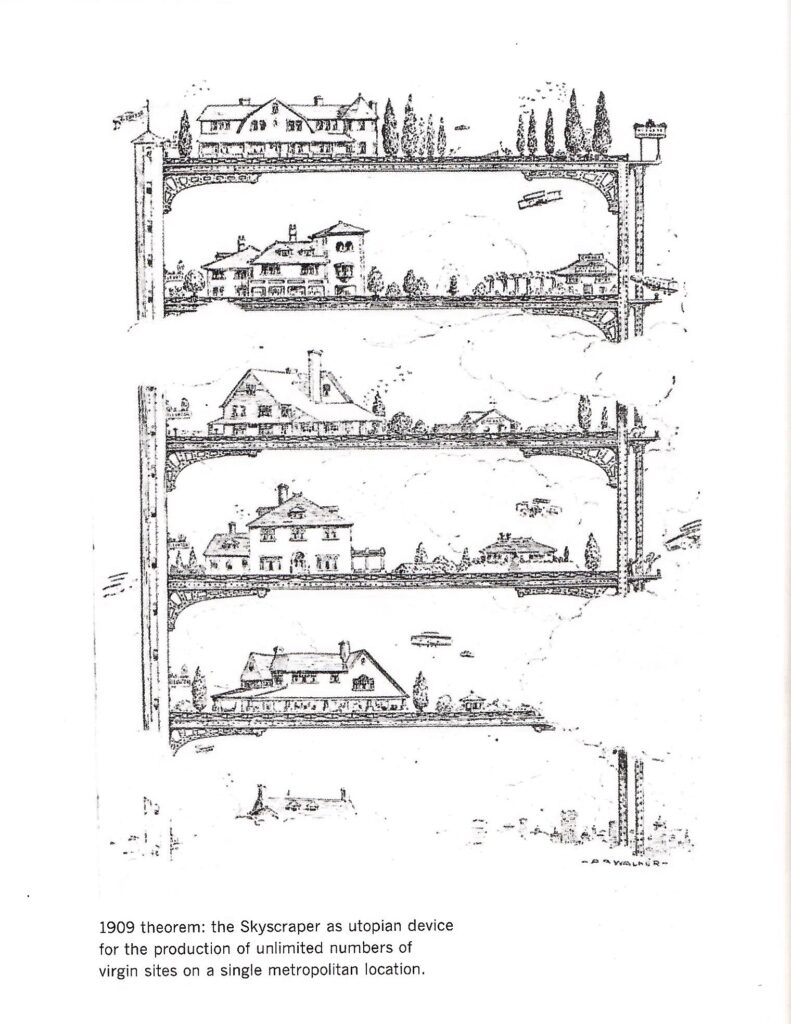

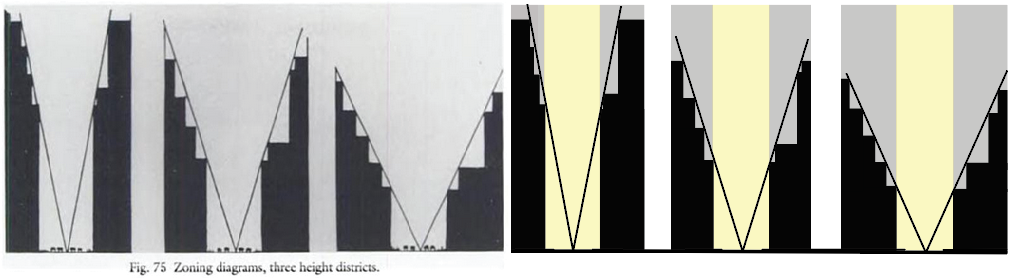

In the early 20th century, Manhattan was being built at a frantic pace. The combination of electric elevators (invented in 1880) and steel-framed construction paved the way for the development of a new typology2—the skyscraper. The 1916 Zoning Law in New York City established limits in building massing at certain heights, which were then used pretty much to the fullest during the Manhattan skyscraper boom. Architects accustomed to the notion that the facade of a building reflects its contents were confused—what kind of a facade could possibly express a jumbled mix of a market, theatre, amusement park, offices, pool, garden and shops within a single building? Hugh Ferriss, who in the perceived hopelessness of the era had changed his profession from architect to draughtsman, drew expressive and dark charcoal drawings that visualised the maximum building massing permitted by the zoning law, and thus, he outlined the spatial fate of Manhattan. The new situation had put a draughtsman into the position of New York’s chief architect.

Koolhaas set himself an almost impossibly difficult task—to discover retrospectively the possibility of creating architecture in a situation where non-architectural practical factors (like the arrival of elevators and steel-framed construction, or the construction boom) are seemingly so intense and overpowering that they don’t leave any room for creativity and conceptuality. What should an architect do in such a situation? How to interpret this culture, and how to create added value that people could relate to? Koolhaas succeeded—he managed to outline an attitude that provided a spatial backbone and cultural sense to the construction of skyscrapers, calling it the culture of congestion. In the density and heterogeneity of different functions, Koolhaas found a situation essential to our contemporary world, which opens up new creative possibilities for the architect and does not necessarily lead to anti-humanistic amplification of metropolitan chaos.

Koolhaas’s playful and subjective way of doing research is notable. His versatile and original research means enabled a sufficiently multi-perspectival view and brought out things that could not be noticed before. What is also remarkable is his non-neutral, even speculative stance. He does not take the position of an observer and describer, but rather asks what can be done with everything he encounters—is there anything with any potential for building an architectural backbone that would result in a viable and culturally generative approach? The stance that was shaped by New York continued to be a guiding undercurrent that can be discerned in much of Koolhaas’s later architectural practice. In Koolhaas’s work, the co-existence and juxtaposition of diverse functions has become a cultural indicator of our contemporary times.

Cultural foreshadowing

The manifesto of congestion that Koolhaas addressed to the Manhattan construction boom has come to life also in early 21st-century Estonia, and also due to non-architectural factors. Just like the rise of “all-in-one” skyscrapers in Manhattan that was driven by practical reasons and lack of concurrent theorising, buildings that are difficult to classify under any familiar architectural typology have started to appear in Estonia. The most telling examples are Suure-Jaani Health Centre (2019, Arhitekt Must) and Narva Study Centre of the Estonian Academy of Security Sciences (2020, 3+1 Architects) that draw together a prima facie surprising assortment of functions, but also the forthcoming state houses for a mix of public services, conceptualised by the Ministry of Finance in 2018.3

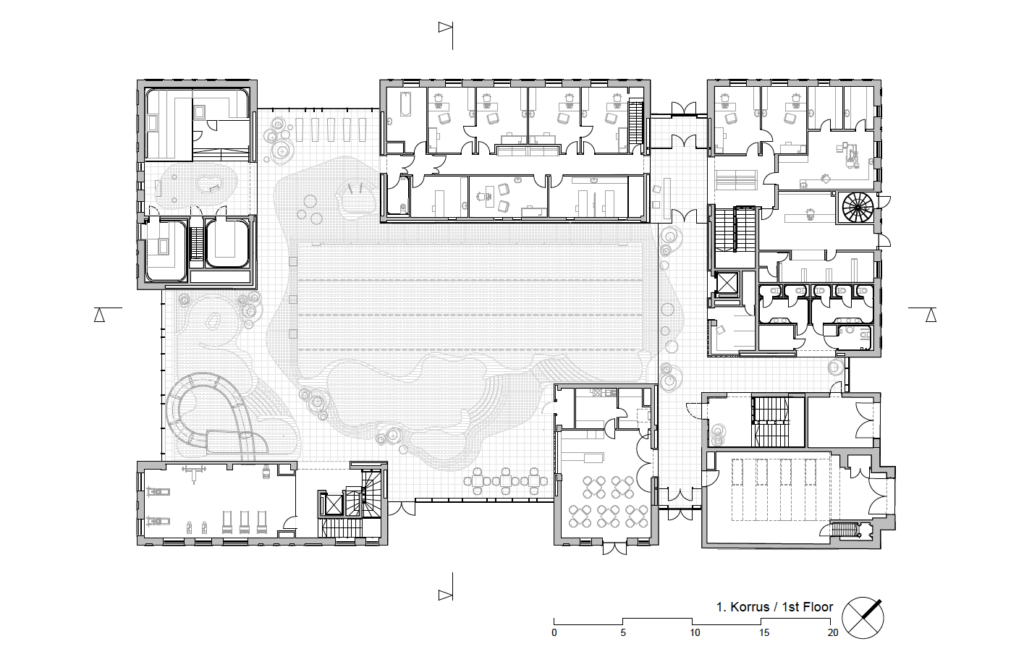

The town of Suure-Jaani with a population of ca. 1000 wanted to build a water park, but decided to add to it several other functions that were in need of contemporary rooms. In collaboration with architect Toomas Paaver, the city government came up with the idea of bringing these functions together under one roof in the town centre, which ultimately led to the building that houses a public swimming pool and saunas, health care centre, dentistry, pharmacy, ambulance, police, cafe and hairdresser. As a matter of fact, combining public functions within a single building is a practice that has been discussed before in the context of small European settlements, given the declining population and digitalisation of services, and it has already been applied in several countries. The Estonian concept plan for state houses also refers to the experiences of Portugal, Latvia and Norway. Italy presented architecturally high-level projects with a similar idea at the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale.

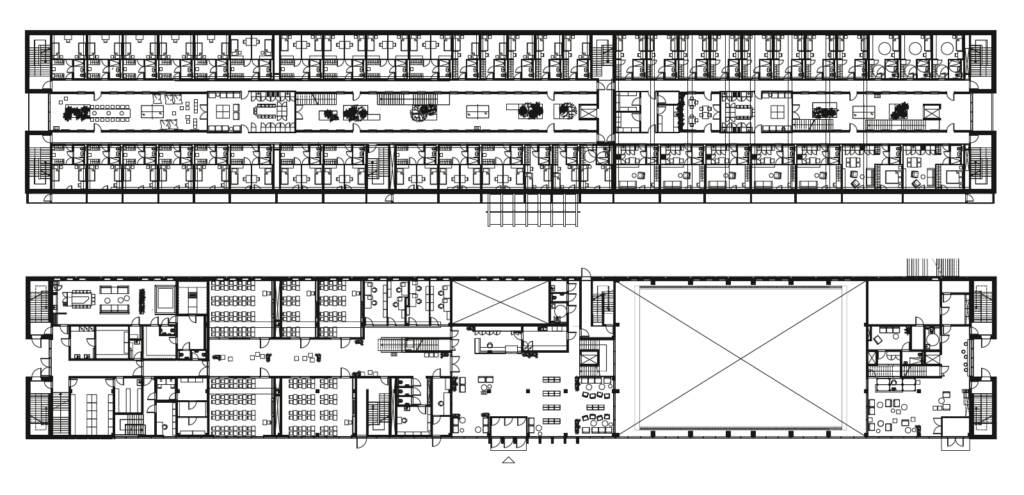

Even though the population of Narva is also shrinking, it does not qualify as a small town in the Estonian context just yet. A combination of public swimming pool, shooting range, seminar rooms, close combat gym and dormitory used jointly by three different organisations might sound like surrealist poetry, but Narva Study Centre of the Estonian Academy of Security Sciences (EASS) that houses this particular list of functions has also perfectly practical reasons for doing so. Several institutions within the administrative field of the Ministry of the Interior were in need of rooms in the eastern region. The new building was a compromise solution to compensate for the unfulfilled promise in the 2016 government coalition agreement about moving the EASS from Tallinn to Narva; at the same time, University of Tartu Narva College was lacking a dormitory, and in the 2017 municipal election, local politicians had promised to rectify the lack of a public swimming pool in Narva. The most gratifying synergy forms somewhat unexpectedly in the dormitory part of the study centre—the EASS trainees are housed together with active duty border guards and rapid responders, and share the kitchen corners and leisure areas in the atrium of the dormitory.

The first architecture competition for a state house to reach the finish line was for the one in Kärdla; the competition ended this year. A new state house for Põlva has been in planning for a couple of years, and in longer term, new ones should appear also in other small towns. On the one hand, the purpose of state houses is administrative cost efficiency; on the other hand, they aim to embody the ideal of giving citizens access to as many services in a single place as possible (making the services more accessible to people with special needs, for example) and offer civil servants possibilities for telecommuting. The competitions for state houses provide architects with good opportunities to reflect on the type of such buildings that accommodate these surrealistic lists of functions, and reflect more deeply on the essence of a contemporary public building. Shall we write the architectural manifesto on designing these colourfully multifunctional buildings retrospectively, or are we conscious of it already during designing?

What kind of architectural approach should we take toward such multifunctional public buildings? It is untenable to proceed from some known building typology, or the notion of a plan and spatial programme supporting a particular function. Neither is it always possible to refer to the synergy created by causal connections between different functions. Right now, the combination of programmes in state houses appears to be rather random—it is based on the current need for rooms for certain functions, or the administrative practicality of bringing them together under one roof. We should also note that these functions or their spatial requirements can change rather quickly (due to public sector reforms and digitalisation). To be sure, if we adopt a Koolhaasian approach, and emphasise the diversity of functions and the people using them, we can see potential for synergy in simply bringing people together. At first, it might seem as the sort of nihilism inherent in a society of the spectacle, but we know very well that new energy and new ideas are born at intersections of different fields, and I think that the kind of design that promotes this is not simply metaphoric. Even though it is merely a small beginning, the public servants working in the so-called superministry building in Tallinn have confirmed that quite a few issues with collaboration across different ministries have been anticipated and resolved in the building’s cafe. And yet, how much openness toward such synthesis-oriented spaces is there in our public sector, and how to interpret democratic communication between citizens and officials spatially?

Specific, often security-related requirements of governmental functions can raise a host of challenges when designing a particular building. The Police and Border Guard Board—one of the users of the EASS Narva Study Centre—is accustomed to relatively closed and controlled buildings, and thus, the Narva Study Centre needed to be made ramming-proof, which usually entails fencing. But the building also needed to accommodate public rooms, including an eight-track swimming pool that had been announced as an election campaign promise. We have to appreciate the brilliance of the architects in finding a visage for the building—several of its looks convey openness as well as astoundingly good dialogue with the surrounding Soviet-built apartment blocks, while protection from ramming was achieved with a stepped landscape. Architects have acknowledged that they were initially baffled by its spectrum of functions, but in the end, they proceeded from the fact that most of the square metres belonged to the dormitory, and took this to be the primary function that would shape the building.4

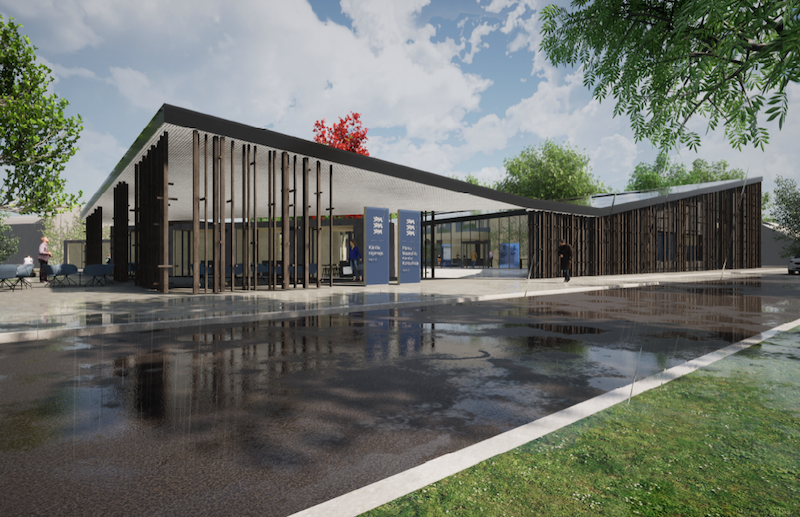

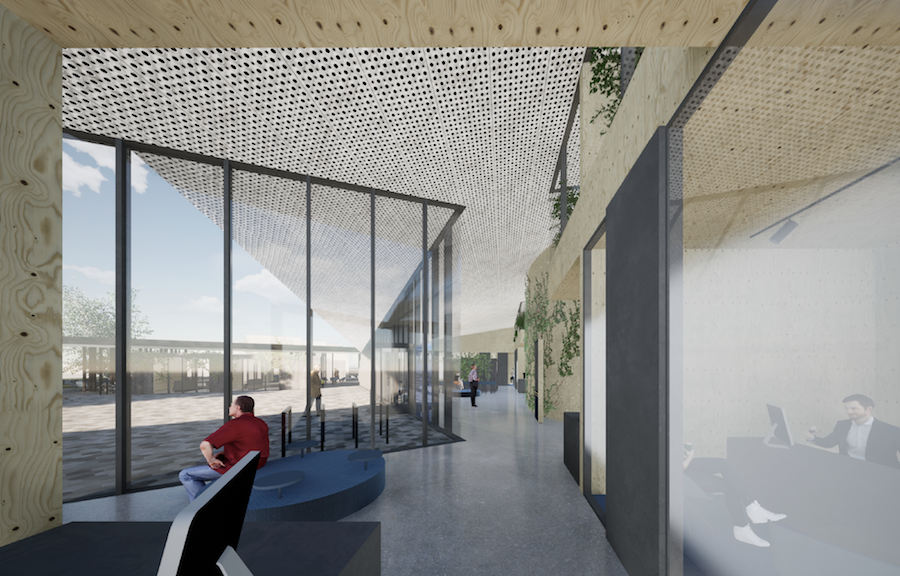

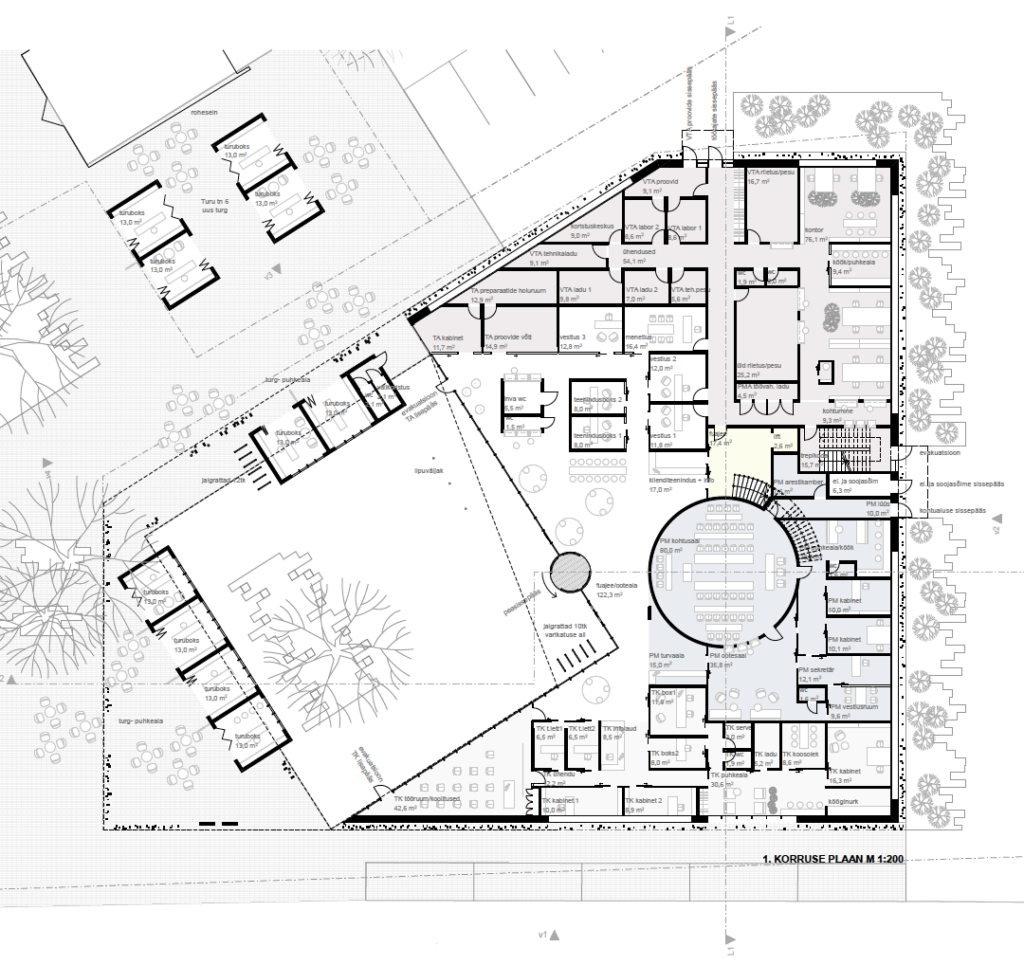

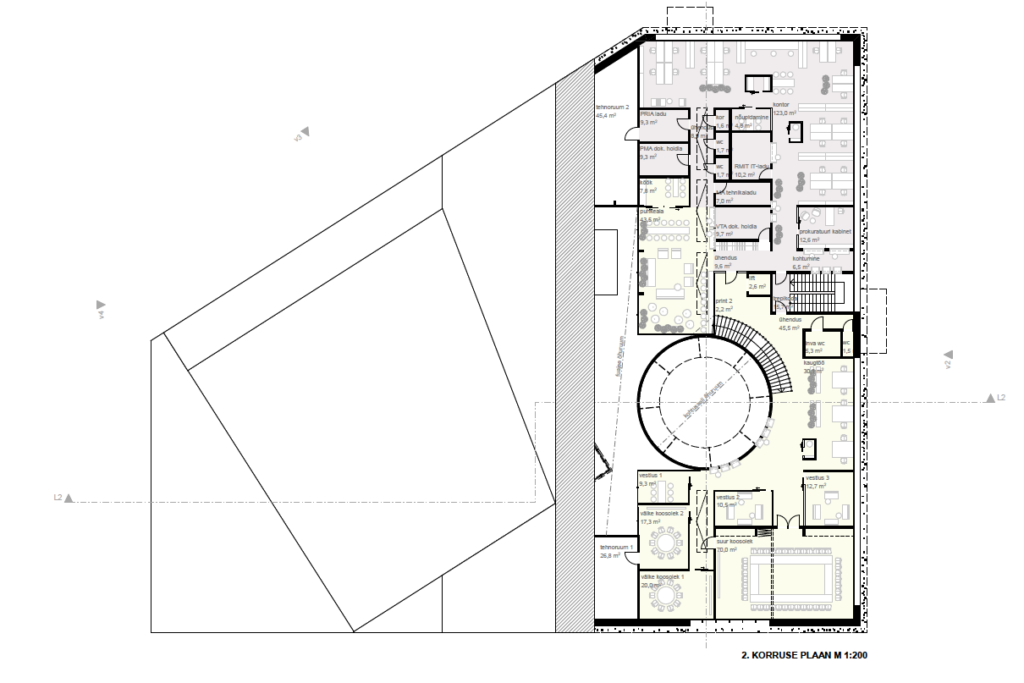

Kärdla state house—sized a little over 1800 square metres and designed by Karisma Architects—will accommodate public servants of several fields (altogether about twenty institutions). Larger rooms are designated to the Agriculture and Food Board and Health Board; other users include the Unemployment Insurance Fund and Pärnu County Court. At first glance, state houses are easily interpreted as workspaces. The competition objects and the very concept of a state house suggest activity-based offices, where each public servant can choose a particular workspace depending on the nature of the task at hand, and change it during the day if needed. Activity-based office is used i4n the Ministry of the Interior, for example, where it is considered rather a success.5 Riigi Kinnisvara AS—the company that manages state real estate—has initiated a collaboration with the Centre for Applied Anthropology to further develop the idea of activity-based offices and spare people from the psychologically harmful side effects of a nomadic work culture. But state houses are distinguished from office buildings by their public orientation—they have to deal with questions like what does democratic space consist in, can there be more diverse forms of communication between citizens and public servants (just like there are more diverse forms of work in an activity-based office), and how does a state house embody the state.

Are state houses and other multifunctional buildings (such as Suure-Jaani Health Centre and Narva Study Centre) the harbingers of the end of typologies, or are there still enough robust practical constraints that will end up shaping a new typology?

On the use and abuse of typologies

The question of typology brings forth a hidden contradiction in architecture, which also happens to be the very thing that makes architecture interesting. To the extent that architecture is art, it is unique. But architecture also has a dimension of functionality, usability, which means that an architectural object has to be to some extent repeatable and thus, typologically characterisable,6 as Rafael Moneo—the winner of Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the 2021 Venice Biennale—writes in his essay „On Typology”. This contradiction between uniqueness and repeatability shouldn’t be seen as schizophrenic, of course. Simply put, a building has various levels of organisation—structural elements (such as doors, windows, walls, etc), logic of construction, spatial solution, relations with the environment and so forth—that form a whole. Bringing these levels of organisation together in space is something that can be approached with uniqueness. Each freedom to combine things is a step toward more unique architecture.

Architects have had different attitudes toward typologies in different times. Architectural typologies have been the basis of architectural education in schools, but also the object of much skepticism. When I was studying architecture in the Estonian Academy of Arts in the beginning of the century, there was a course called building typologies in the curriculum. Today, this course has disappeared from architects’ timetables. Students need to design a pavilion, private residence, four public buildings and an apartment building, and introduction to the respective typologies is integrated to each project course.

Typology-based approach to architecture does not seem that interesting and fruitful today—knowledge of typologies is not a good starting point for creating an architectural work. However, on the subject of typologies, it is interesting to reverse the future-oriented thinking that is so typical in architecture, and examine how typologies have transformed over time. In his magnificent essay „Figures, Doors and Passages“, Robin Evans studies how the layouts of residences have changed from the 16th century up to the 20th century.7 Evans’s essay suggests that since floor plans have changed rather slowly, we tend to think of them rather as a pragmatic and culturally insignificant phenomenon. Looking at longer time periods, however, it becomes clear how the ground plans of residential buildings embody the mentality of their time and synchronise with current cultural manifestations. For instance, High Renaissance villas had a matrix-like floor plan—rooms had several doors and moving around in the building meant choosing between several different possible trajectories. Space was favourable to randomness and fortuitous encounters—in the literature of the time, people were mostly depicted in social settings, while solitude was uncommon. Classicism brought the triumph of the corridor—buildings with single-door rooms had determinate trajectories for movement. The literature of that period warned against socialising without a particular reason, and often depicted the human soul as a solitary chamber.

Evans’s examples concern residential buildings (even if they often happen to be villas or palaces with many diverse users), but nevertheless manage to show that a building plan can be a Deleuzean diagram that guides and shapes our lives much more deeply than we initially think.

Thinking about experientially interesting modern-day or thoroughly renovated buildings—such as Kultuurikatel, Fotografiska, Kai Art Centre, University of Tartu Narva College—it is quite clear that in addition to skilful interplay of functions, comprehensibility and readability are also important. Furthermore, equally important is the visual impact and multifaceted relatability of these buildings. The popularity of Kultuurikatel as a venue for conferences on digital matters has been explained by urbanist Maroš Krivy—the digital field is difficult to represent, but can be alluded to with tellingly dilapidated and manifestly superseded industrial heritage.8 Interestingly, this figurative interpretation leads us back to the anguish of New York’s architects—what do the aesthetics of these buildings tell us? The form of Kärdla state house prefers to remain silent—it does not comment on the nature of state and keeps a rather low profile, entering into dialogue only with the tectonics of the surrounding historical roofs. It is almost as if it has no face at all—which is certainly better than presenting an artificial and implausible face—but focuses only on public relations. Given the no-nonsense institutions that it accommodates, the architects of the state house say that they aimed for a maximally friendly building. This is why guests will be greeted by a spacious foyer even before they reach the security gates. Kärdla state house creates spaces with varying levels of openness toward the public—its courtyard is turned toward the central square of the town, which in turn adjoins the market. So the spatial diversity of the state house could indeed be interpreted as one attempt to find a spatial equivalent of democracy.

The 20th and 21st centuries have brought immense social changes and many new issues—these changes should also be reflected in the designs and typologies of public buildings. What kinds of plans, spatial solutions and typologies could reflect an increasingly egalitarian, life-long learning, globalised, hybridised, technologically advanced society? The current popularity of contextual architecture in Estonia carries a danger—messages from the past can be heart-warming, but architecture should also bring messages from the future. As we go along with the pragmatic flow of everyday life, it is easy to think of it as inevitable and just bathe in it giddily. But what kind of culture will this pragmatic flow lead to—what kind of culture will this mentality cultivate?

KAJA PAE is an architect and physicist, editor-in-chief of Maja since 2017(-2022).

HEADER: Hugh Ferress’drawing of skyscrapers, 1924. Source: MoMA

PUBLISHED: Maja 106 (autumn 2021) with main topic Spatial Revolutions

1 Rem Koolhaas, Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan (Oxford University Press, 1978).

2 Building typology is the classification of buildings based on their physical parameters and uses, and the study of this classification.

3 „Riigimajade loomise kontseptsioon“, Rahandusministeerium 2018. https://www.rahandusministeerium.ee/sites/default/files/riigimajade_loomise_kontseptsioon_2018.pdf

4 Markus Kaasik, „The Pragmatics and Alchemy of Contemporary Architecture“ Interview by Ülar Mark, Maja no 104, spring 2021, pp 36–54.

5 Video clip „Sotsiaalministeerium tegevuspõhises kontoris“: https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=247857569305982

6 Raffael Moneo, „On Typology“, Oppositions, no 13, summer 1978, pp 23–4

7 Robin Evans, „Figures Doors and Passages“, Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays (MIT Press, 1997), pp 55–91.

8 Maroš Krivý, “Theoretically Grounded Architecture: Where Did it Disappear?” Interview by Kaja Pae, Maja no 100, spring 2020, pp. 17–18.

.