SMART

The cultural shift towards using materials and energy that are contained within planetary boundaries requires a reconsideration of the most fundamental assumptions about how buildings interact with the world.

Designing with a territory values connection over extraction. Clara Kernreuter from Atelier LUMA and Maria Helena Luiga from kuidas.works discuss bioregional design.

Although dictionaries define the term ‘plateau’ as a stable, fluctuation-free state, they also include a caveat: it only lasts for a certain period of time. So, what comes next?

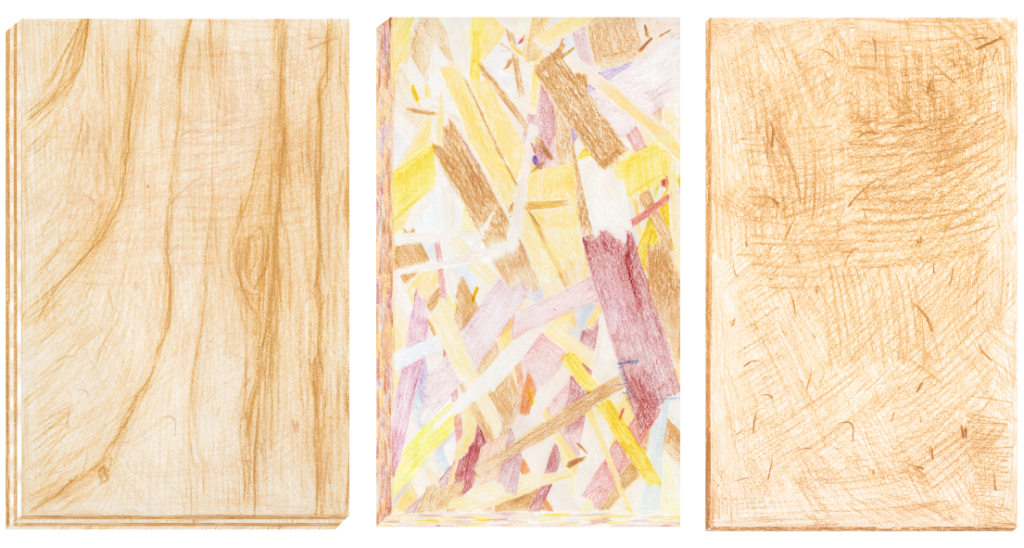

Authors traced the bigger processes that are connected to the production of engineered wood - these materials are produced from industry leftovers, but also from trees that are cut for that purpose only.

The nostalgic image of an architecture office full of drawing boards and rapidographs is alien to the generation born after the restoration of Estonian independence. We began our architecture studies by acquiring basic computer skills and then boldly plunged into the world of 2D and 3D, visualisation and BIM design.

Maxime Cunin of Superworld writes about designing infrastructure of and for sharing.

Antoine Picon is the G. Ware Travelstead Professor of the History of Architecture and Technology at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and chair of the PhD program in architecture, landscape architecture, and urban planning. In addition to his activities in Boston, he is closely connected to Tallinn and the Estonian Academy of Arts, where Antoine Picon supervises PhD students and advises the Faculty of Architecture. Recently, the university awarded him an honorary doctoral degree—Doctor Honoris Causa—for your achievements and support.

When a certain building technology or material is sidelined for an extended period, one is bound to get the impression that it is intrinsically obsolete. This has happened with natural stone, which architects, when asked about its potential for use, describe only as being too expensive, too labour-intensive, incompatible with the public procurement system and, as can be witnessed in renovation projects, simply too complicated to build with. The inability to imagine a future different from the present is typical to the 21st century, and hence, the main use of limestone in Estonia remains blasting it into rubble that can be utilised as landfill and concrete aggregate.

Improving the architectural quality of the existing housing stock requires integrating engineering solutions with architectural decisions. In the ongoing renovation marathon, it is important to discuss what kind of added value could be drawn from the existing to unleash the full spatial potential of renovation and to create good user-friendly spaces, writes Diana Drobot.

Postitused otsas

ARCHITECTURE AWARDS