SPATIAL DESIGN

In the search for architectural strategies in times of a worsening climate crisis and diminishing resources, vernacular architecture has moved into spotlight. This is mostly due to its ability to passively respond to the local climate and make use of the ‘as found’—not only in terms of natural resources and building materials, but also in terms of available craftsmanship and local communities’ skillsets. Valuable knowledge of vernacular architecture, a pragmatic yet poetic, and in fact a scalable concept, is mostly passed on through buildings themselves as epistemic artefacts.

As a country that has experienced Europe’s biggest increase in real estate prices, we will soon face the question: how to avoid reaching the top in segregation and spatial inequality too? Hannes Aava explores.

Laura Linsi writes about the architect and educator behind ‘A Moratorium on New Construction’—the initiative that argues in favour of reviewing what in space production is desirable and what has ceased to be so.

In the course of the programme ‘Great Public Spaces’ dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the Republic of Estonia, the historic street was reconstructed as a contemporary pedestrian-friendly main street. The light monochrome hues of the design create a museum-like exposition complemented with seats, planting, lamps and signage engraved in the pavement and providing information on particular buildings, architectural and landscape objects as well as the town in general.

The field of spatial heritage comes with a kaleidoscopic array of concepts that connect the subject with issues such as the climate crisis, reuse, architecture and urbanism. The used terms need to be clarified and made more familiar.

Why is it no longer possible for 21st-century Estonia to continue without a spatial development office, and what kinds of new values would the new office create?

How about we agree that from here on out, we will be implementing only good spatial solutions? Okay?

In order to compensate for the bureaucratic inflexibility and sluggishness that is burgeoning in spatial design, a new methodology has evolved that enables to operate in a more democratic, playful, experimental and cost-effective way.

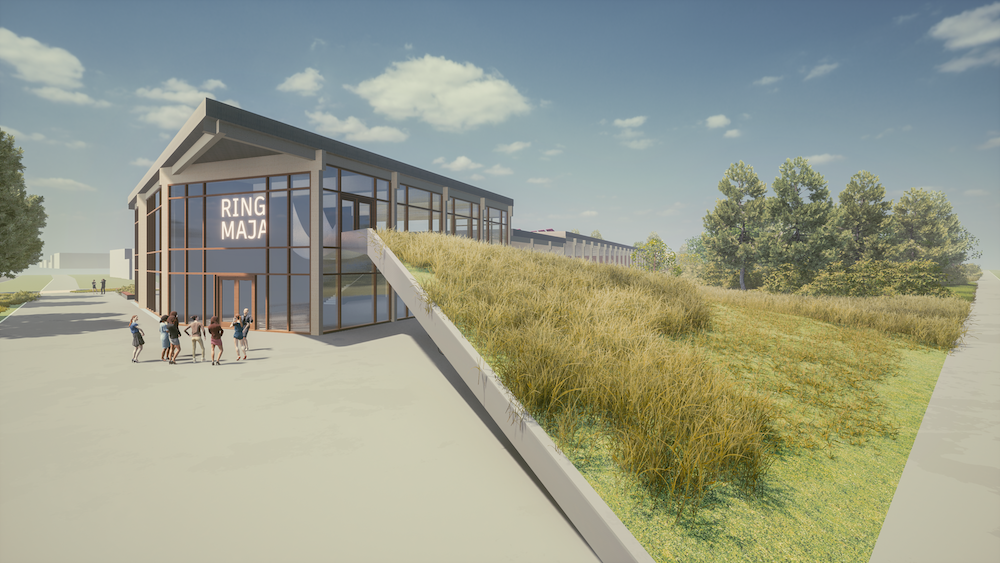

The circular economy centre highlights the potential of waste materials as a reusable resource. It creates possibilities for repairing, reprocessing and using things again.

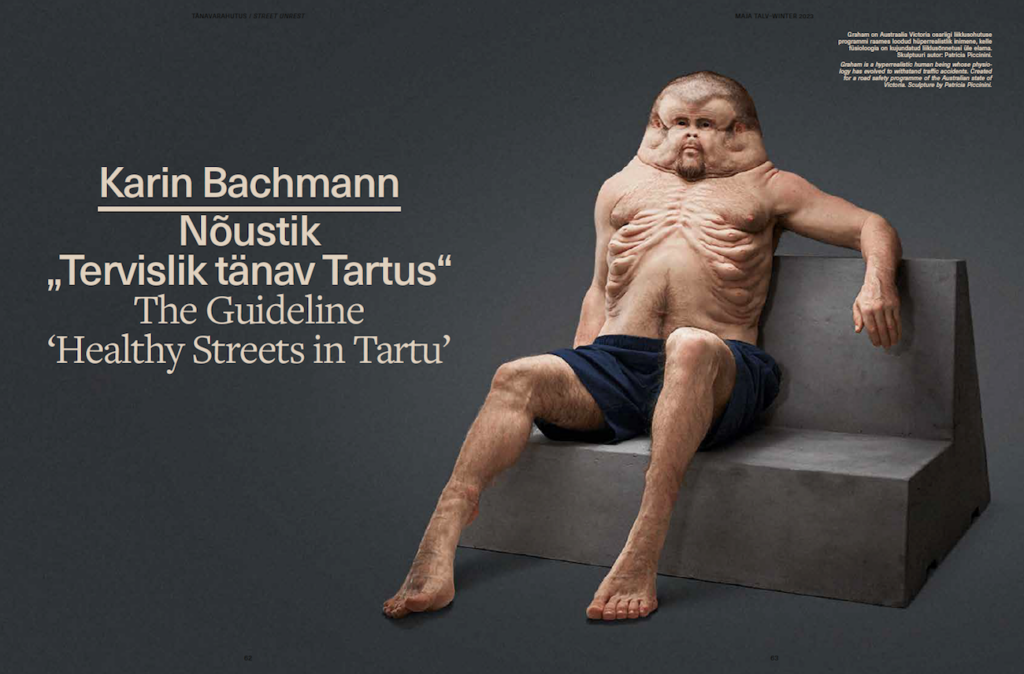

Healthy Streets in Tartu is a guideline providing help for city officials or specialists working on spatial design.

Postitused otsas

ARCHITECTURE AWARDS