The field of spatial heritage comes with a kaleidoscopic array of concepts that connect the subject with issues such as the climate crisis, reuse, architecture and urbanism. The used terms need to be clarified and made more familiar.

Across the discipline, we keep hearing of preservation practices—this is where the practical and theoretical issues of heritage discussions come together. Heritage ‘preservation’ might give a misleading impression of something static and unchanging, so perhaps it would be good to replace it with some other term that has a broader semantic field.

There is a lot of passionate discussion about who constitutes an heritage expert. Theoretical writings also make use of the term authorised heritage discourse, which draws attention to the fact that we have historically developed assumption that the key thing in interpreting cultural heritage is expertise. The ways in which heritage is interpreted in the society become clearer by studying the practices of heritage creation, which highlight the fact that interpretations of built heritage are connected to decisions about what to preserve, and how to mark and mediate what has been preserved. This underlines the point that spatial heritage is not some objective category to cover all the built heritage that could be considered ‘old’.

Attempts to revitalise historical city centres and find new purpose for valuable buildings have led to the introduction of terms that enable to connect heritage protection with urban development. One example would be the term heritage-led development, which is still only taking root in Estonia and has not been fully unpacked even by people working in the field. The combination of ‘heritage’ and ‘development’ might come off as somewhat paradoxical—how exactly could protection, preservation and regulation of these practices be connected with development (of a place, urban area, space)? In general, there has been a significant mental shift in the heritage discourse, which accentuates the fact that enlivening urban space by investing knowledge and financial resources in heritage environments creates more sustainable communities with unique identities. In the discussions on heritage-led development, heritage protection is associated with place and spatial design practices.

Probably somewhat more familiar is the concept of adaptive reuse, which stands for finding new, modern uses for buildings that have lost their original function. Different cultures have been repurposing buildings throughout history, but the term kind of started to trend in the 1970s and 1980s—in connection with, say, adopting industrial buildings as artists’ studios or spacious living spaces. Today, adaptive reuse is mostly associated with appreciating spatial diversity and acknowledging that keeping already existing buildings in use is significantly better for the environment than building new ones (even energy efficient ones). ‘The greenest building is the one that already exists’ has become the favourite slogan of heritage experts. There is room for improvement, however, when it comes to material reuse—in the field of construction, circular economy is still in many ways in its infancy.

The field of nature conservation, which is also connected to preservation, makes use of the term convivial conservation, which emphasises the fact that nature conservation is not merely an activity that springs from aesthetics and scientific findings, but also an economic and political issue. Looking at modern interpretations of spatial heritage, it seems that it is increasingly important to consider the existing environment more broadly than on the level of individual buildings—by granting significance also to the space between the buildings—but also to dissect the ideological framework around heritage protection and creation.

KAIA-LUISA KURIK

HEADER: Pärnu. Photo by Piltnik Kärt

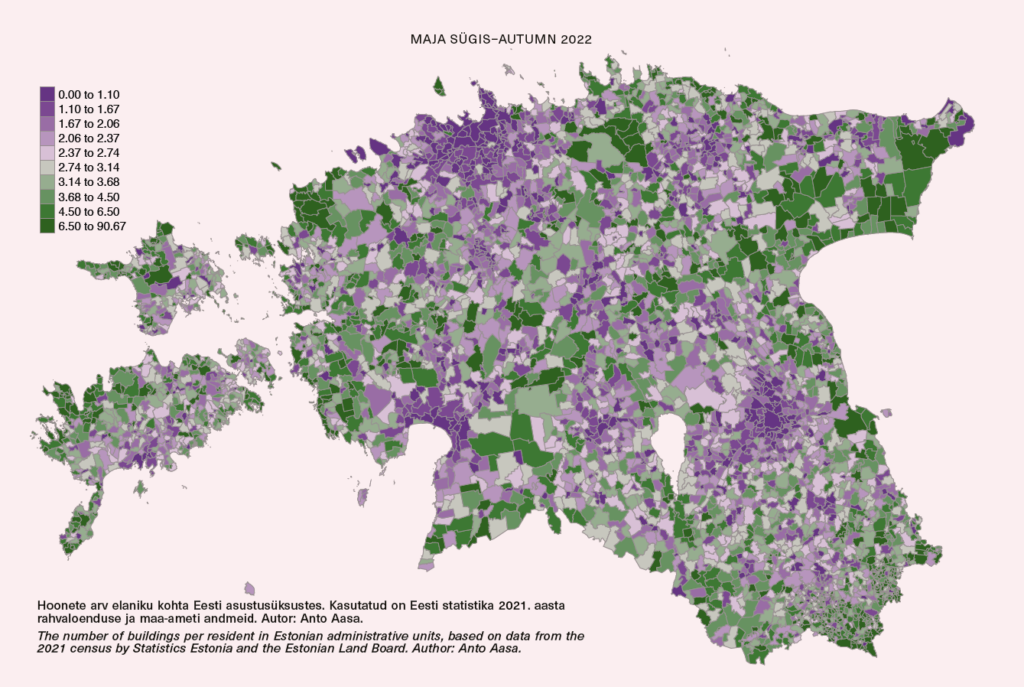

PUBLISHED: Maja 109-110 (summer-autumn 2022) with main topic Built Heritage and Modern Times