Why is it no longer possible for 21st-century Estonia to continue without a spatial development office, and what kinds of new values would the new office create?

Approximately a quarter of all companies in Estonia are directly involved in the construction and real estate field.1 In order to have high-quality living environment around us, all these companies and people would need to act in a unified and coordinated manner. But who should govern the process? Public sector creates the preconditions for making their output comply with social interests. Both the central government and municipalities have their own roles to fulfil. The central government ensures a uniform legal framework, and steers the nationwide spatial design framework by providing funding measures and quality criteria, developing information systems and databases, drawing up guidelines, organising training, commissioning studies, laying down strategic plans, etc. Municipalities make mostly individual decisions regarding their own territories, in order to ensure a balance between nationwide and local interests. Unfortunately, time and again we get examples of ill-conceived spatial decisions, which result in disregarding the interests of many users as well as inefficient use of resources. We should not look for a culprit, but rather improve the cooperation between the state, local authorities and entrepreneurs.

How is high-quality living environment born?

The administrative system in Estonia is very centralised. In Finland and Denmark, for example, around three quarters of public sector employees work for municipalities and the rest for the central government, while in Estonia, the ratio is reversed.2 Estonian municipalities are very dependent on the central government also financially. In spatial policy discussions, it is sometimes pointed out that the administrative reform should be continued all the way up to county borders, but from a proportional perspective, reshuffling the administrative divisions does not help to add resources to municipalities. Whether we like it or not, the next decisive steps in spatial policy need to be taken with Estonia’s centralised governance system taken into account. In addition to its potential problems, let us also take note of its opportunities. Centralised solutions enable to fulfil broader development needs of the society in a uniform way.

Our security, environment, public health and economic success depend on solving various new national and international challenges that have risen in the crisis years. Many of them seep into spatial decisions. Some recent examples include the need to develop renewable energy production, power grids and efficient district heating networks; to renovate houses and hospitals, develop civil protection infrastructure, etc. The more uniformly all of this is addressed across the country, the more efficient, quality-oriented and consistent is the business environment for our entrepreneurs. Although Estonia has indeed a range of very different municipalities (it is difficult to compare the city of Tallinn and the tiny, insular Kihnu Parish, for example), some of the major municipal issues, such as urban sprawl, declining old towns, population decrease and renovation needs, are nevertheless common to many municipalities. It is quite obvious that tackling these issues independently exceeds the capacities of most municipalities, especially when we keep in mind that the 79 municipalities of Estonia employ altogether a mere 25 certified architects and a limited number of planners.

Poor investment prospects of municipalities do not amount to a lack of spatial decisions. The quality of space is affected by every plan or building permit issued, public transport stop or timetable change, public maintenance, waste management contract, location of public services, etc. It is important to see the interconnections between the decisions. Making spatial decisions based on 793 different approaches are often controversial and un-governable. Although in terms of employee numbers and budgets, the administrative order in Estonia is very much inclined towards the central government, this does not show in spatial policy. Spatial decisions are steered by several ministries and state institutions, and spatial design related matters are handled by different ministers, institutions and parliamentary committees. Thus, key decisions in spatial policy are indeed centralised, but medium-level decisions are nevertheless dispersed, which, given our small population and otherwise efficient approach to public administration, does not lead to good results.

In addition to the fragmentation of spatial design related issues, no one on the national level is tasked with shaping a comprehensive and high-quality living environment. And yet, one of the five foundational goals in the government’s development strategy ‘Estonia 2035’ concerns ‘living environment [that is] considerate towards everyone’s needs, safe, and high -quality’.4 The green transition action plan for 2023–2025, published by the Government Office in the beginning of 2023, sets high-quality living environment as one of its three main goals. As of now, these documents do not specify how and by what activities are we supposed to achieve this holistic and quality-oriented living environment. The least we could do right now is to create a state institution with strong spatial competency that could help the decision-makers on different levels—a spatial development office. It is noteworthy that similar national units have been established also in some countries where municipalities have much stronger powers, the closest analogy being Boverket in Sweden, which also employs the state architect of Sweden.

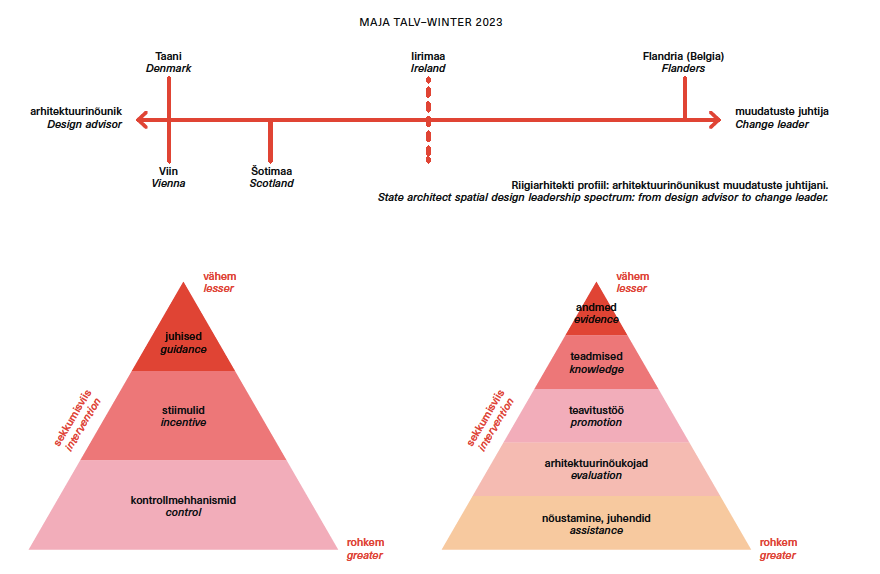

The work of a spatial development office could be compared to that of state architect offices, which have been established in various parts of Europe. In the Netherlands, the history of the state architect goes back already a couple of centuries. In the recent decades, state architects or regional architects have been appointed in Flanders, Ireland, Scotland, aforementioned Sweden and other places.5 Australian and U.S. states likewise have a long tradition of state architects. Although their activities do not fully overlap with the European model, it nevertheless shows the dedication of government authorities to promoting spatial design, and improving the spatial competency of the public sector as well as the broader public. The reason for establishing state architect offices or other units like the spatial development office is quite clear—mere spatial planning and construction laws, existence of general plans, processing of detail plans, issuing building permits or other currently regulated processes alone do not provide everything that is needed for creating desirable living environment. Spatial planning and regulated construction do not automatically lead to high-quality outcomes. Having minimum requirements helps to avoid the worst, but in order to enable the best possible solutions, we need much more commitment. Thus, improving the state’s spatial design capacities, and the work of teams like the spatial development office both on the municipality and central government level, are of critical importance in creating a more sustainable built environment.

Good spatial decisions require a comprehensive view

Spatial policy is shaped and implemented by very different administrative levels and sectors; synchronising the operations of so many parties is complex. And yet, state architect offices in other countries have managed to gather different government agencies responsible for spatial design around the same table, persuade them to observe quality goals throughout, and organise broad-based discussions of various spatial solutions that take into account the interests of as many target groups as possible. The initiatives and activities of state architects have thus broadened also the opportunities for closer cooperation in the society, which is a necessary basis for better spatial solutions, leading to more efficient and better-organised administration.

The agreement ‘Long-Term View in Construction 2035’ between ministries, universities and professional associations sets the goal of improving the municipalities’ long-term planning capacities, both in terms of spatial planning as well as investments. Spatial planning and well-considered land use are some of the key tools that lead to high-quality living environment, together with comprehensive long-term planning of investments and incentives.

Widespread examples exist of the opposite, i.e. overly simplified and short-term oriented decisions, such as locating municipality buildings to random property at hand, and unconditional sales of properties that have national or social importance. Without a strategic perspective, individual narrow-sighted decisions will result in poor placemaking culture and disconnected spaces with impoverished potential for generations to come.

An often-recurring scenario is where a town with a declining population decides to build a new school building, often on the edge of the town, thus contributing to urban sprawl, instead of reconstructing some historically valuable building in the city centre and hence contributing to the compactness of habitation. The decision by the creators of the new Kohtla-Järve State Gymnasium to forsake and not renovate one of the most brilliant piece of Estonian school architecture from the 1930s, a school building designed by Anton Soans, is just one example of one-dimensional decisions that fail to take the whole social and economic picture into account. Troublingly shrinking Valga recently built a new vocational education centre on the edge of the town, all the while the National Heritage Board is looking for ways to save declining city centres with the project ‘Historic Town Centres Revitalised Through Heritage-led Local Development’, and the state is supporting the reconstruction and revital sation of the historical heart of Valga-Valka. As these examples evidence, the contradictory and uncoordinated investments by different state institutions are not merely a waste of resources, but also leave Estonians without high-quality living environment that would bring people and communities together in an empowering way.

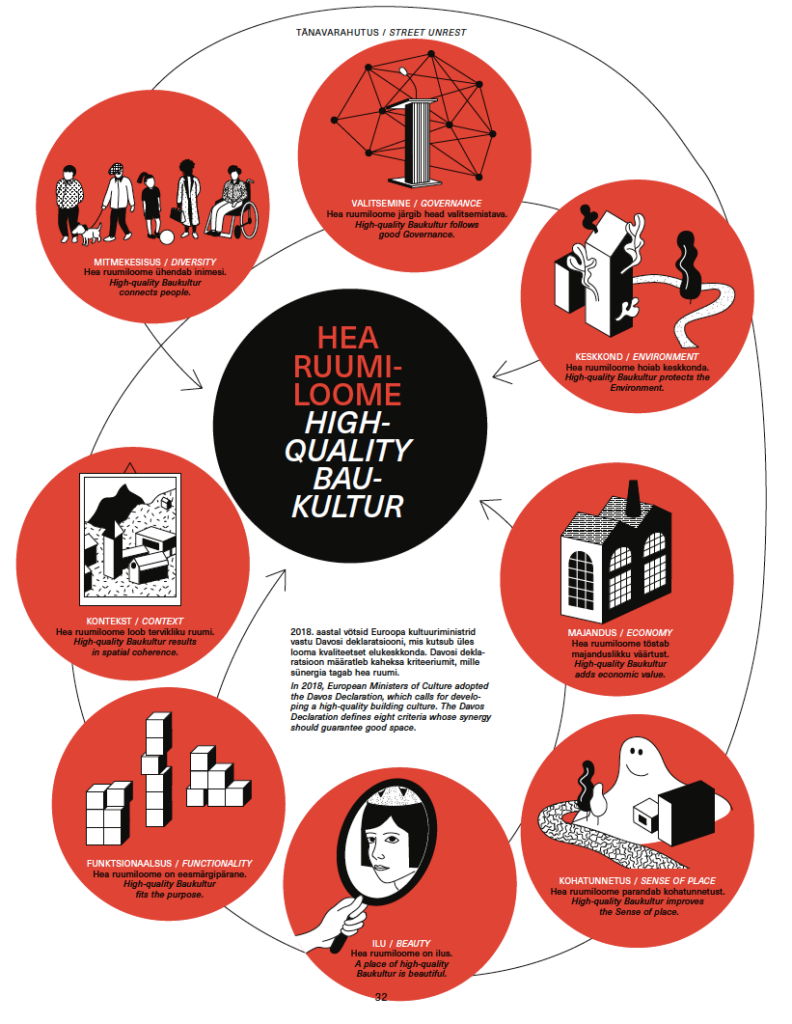

On the other hand, Paide State High School, completed in 2021, is a much better example of a versatile spatial solution that reckons comprehensively with the bottlenecks of the Estonian society and economy. At first, placing the state gymnasium in this centrally-located historical school building, which had been waiting for a new use for decades, was considered impossible (among other things, the planned number of students implied a larger building), and the new school was going to be established in a typical Soviet-era school building on the edge of the town. That the Ministry of Education and Research, State Real Estate Ltd. and the National Heritage Board eventually found a common language and agreed to adopt the historical schoolhouse sitting on the side of Castle Hill instead is thanks to many years of dedicated voluntary work by the Union of Estonian Architects. Counting on this kind of enthusiasm is not sustainable, however, and not even conceivable on the Estonian scale, but the fortunate example of Paide State Gymnasium gives an idea of how a spatial development office with a comprehensive view of spatial design could contribute to creating valuable environments. The adopted old schoolhouse brings life to Paide’s declining old town, ensures better access to the school, promotes moving on foot, and functions as a community centre, not to mention featuring a high-level aesthetic solution that enriches Paide’s milieu with an ensemble of old and new, and offering a modern study environment. We can say that in this particular comprehensive solution, the principles of high-quality living environment put forth in the Davos Declaration—management, functionality, environment, economy, diversity, context, sense of place and beauty—are implemented in a convincing and synergetic way.

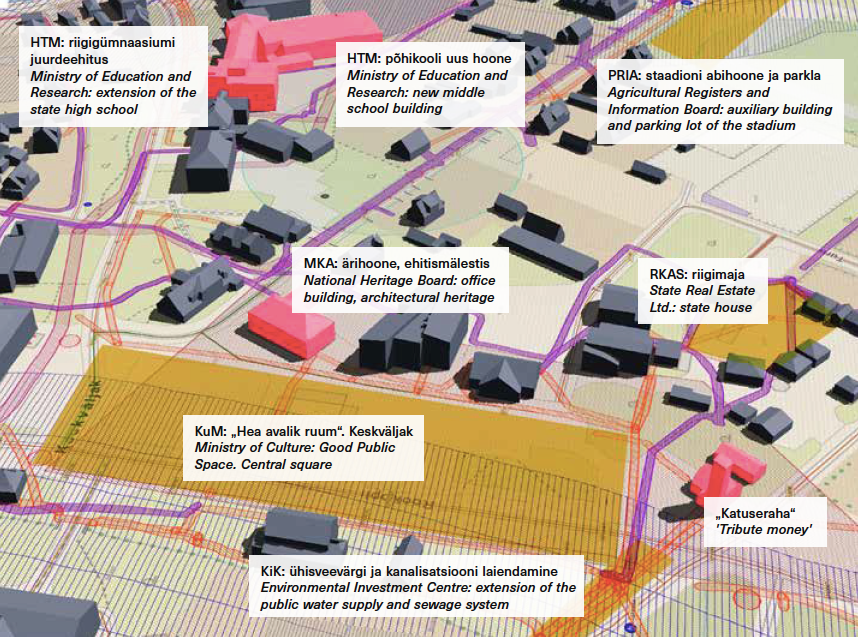

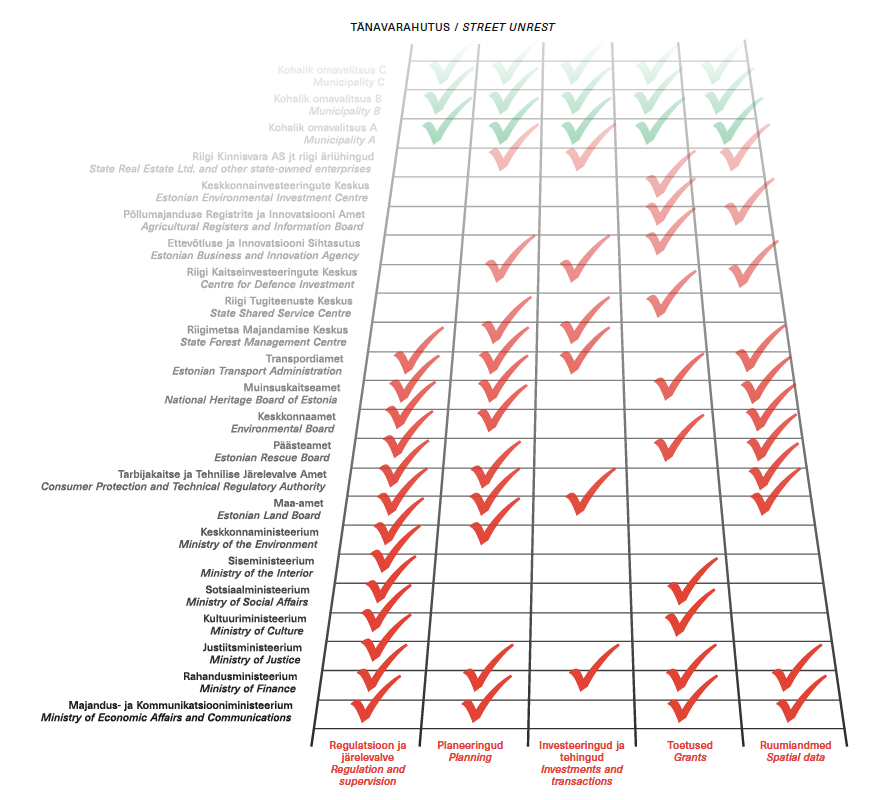

Local-level spatial decisions are largely dictated by conditions set by the central government. Legislation specifies what kinds of solutions should be achieved with the grants given. In case of investments, decisions are determined by the state as the commissioning party. The state generally adheres to best practices of involving municipalities and other parties, but this in itself is insufficient to guarantee a harmonious outcome. The messages given out by the state are confusing, pulling the spatial decisions of municipalities in too many directions. In addition to countrywide investments of state institutions and state-owned enterprises, there are grants, coordinations, various rights for land use and building, real estate transactions and spatial data collection, all run by state. In the centre of a typical small town, one will quickly find buildings that have been built, renovated or revived with support from the state, state-supported district heating, plumbing and sewage lines, state-supported renewed streets, and also an occasional state-supported new central square, so-called ‘state house’ (a centre concentrating the services of various agencies) or rental apartment building. The conditions and data on which the decisions are based come from many different state institutions (see figure).

For instance, in their own specific ways, several government agencies give out similar subsidies for reconstruction, which are at times also duplicated by the initiatives of municipalities. There are some felicitous comprehensive solutions such as Elva’s Central Square and beach promenade that can be rejoiced in, but it is in the interest of the state that these would not remain isolated cases. It would be much more efficient to design different support measures in a way that would make them complement each other, thus ensuring a better, more comprehensive living environment. There should be a single special-purpose coordinating unit responsible for the state’s conditions and messages regarding spatial design—a role that could be successfully fulfilled by a spatial development office.

The need for a spatial development office qua unitary competence centre has been highlighted for years both in private and public sectors. It was compellingly underlined by the Spatial Design Expert Group established by the Government Office in 2017, and the subsequent national working groups. By now, the idea has found a place in various official documents. The spatial development office would not enlarge the state apparatus—its success lies in concentrating already-existing functions. There would be an obvious synergy between the tasks of implementing the state’s land and real estate policy, directing investments, participating in planning, arranging various land transactions, collecting and enhancing spatial data, developing digital environments for procedures, giving out grants, counselling, training, and representing the state’s spatial interests on the international level. The spatial development office would refrain from making local-level decisions, but offer the local decision-makers support that is based on the best expert knowledge and most recent data.

In addition to better public administration and coordination of activities, there is a need for vision-building that would involve different parties, which is something that the spatial development office would also promote. An example from abroad would be ‘Panorama Netherlands’,6 a project initiated by the Dutch state architect that concerns the spatial future of the Netherlands up to the year 2050. These sorts of projects do not supplant official administrative agreements such as nationwide planning, but they do encourage discussion of new conceptions and solutions among local residents, municipalities and the private sector across the country. The purpose of the interdisciplinary initiative ‘New European Bauhaus’, which connects the Green Deal with living environment issues, is to create inspiring, sustainable and inclusive living environments. The question presented by the climate crisis is largely a question of new, sustainable kinds of spatial design, and thus implies taking a spatial view of human activities and culture at the outset. It is not for nothing that Ursula von der Leyen has called ‘New European Bauhaus’ the soul of the Green Deal.7

Estonian spatial development office could offer a similar integral view on living environment, which is inevitably needed in the 21st century, and work as an influential leadership unit whose well-conceived spatial decisions and good advice can always be counted on by the central and local authorities, as well as private sector and broader public.

IVO JAANISOO is the Deputy Secretary General for Construction in the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communications.

KAJA PAE is the Head of the Construction and Housing Department in the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communications.

VERONIKA VALK-SISKA is the Head of Housing Policy in the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communications.

HEADER: Paide State High School. Photo by Terje Ugandi

PUBLISHED: Maja 111 (winter 2023) with main topic Street Unrest

1 Statistics Estonia, EM001: ETTEVÕTETE MAJANDUSNÄITAJAD TEGEVUSALA JA TÖÖGA HÕIVATUD ISIKUTE ARVU JÄRGI, https://andmed.stat.ee/et/stat/majandus__ettevetete-majandusnaitajad__ettevetete-tulud-kulud-kasum__aastastatistika/EM001

2 Olev Raju, Kohalike omavalitsuste rahastamisest Eestis (Riigikogu Toimetised, December 2005), https://rito.riigikogu.ee/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Kohalike-omavalitsuste-rahastamisest-Eestis.pdf.

3 The number of municipalities in Estonia.

4 ‘Estonia 2035’, https://valitsus.ee/en/media/3926/download.

5 Learn more about the 2019 study of the basic principles of high-quality space here: https://www.kul.ee/media/809/download. A follow-up study on the same topic can be found here: https://www.uur.cz/media/w3opgxzy/state_city_architects_20221004.pdf.

6 College van Rijksadviseurs, ‘Panorama Netherlands (English Summary)’, https://www.collegevanrijksadviseurs.nl/adviezen-publicaties/publicatie/2019/11/18/panorama-nederland-engels.

7 New European Bauhaus, https://new-european-bauhaus.europa.eu/index_en.