How about we agree that from here on out, we will be implementing only good spatial solutions? Okay?

Very well, let us agree. Let us also put our agreement in writing. Sure, let us put it into law that there shall be only exemplary spatial solutions.

Someone should also manage that implementation of good spatial solutions on the level of the state. Keep an eye on it so that no bad solution would slip through, and give advice and a helping hand. Another fine idea—why not!

Architects have occasionally entertained this sort of basic train of thought in the last couple of decades, sometimes in a more focused way and other times more dimly, sometimes with an urge to act and other times as a mere fantasy. Sometimes it has been driven by an aspiration to be useful to the society, other times by a selfish desire to issue invoices to someone, or vanity, or self-sufficient wisdom or some other nicer or not-so-nice motive. We can’t say that we haven’t got anywhere with it; neither can we say that we have really implemented the idea.

The power of these sorts of agreements can be either enormously large or vanishingly small in a democratic capitalist society, depending on whether and how the agreement is understood, either observed or ignored, as well as many other agreements and the hierarchy between them. In a small country, a lot hangs on specific people and their way of doing things. In what follows, I will try to ponder a bit the possibility of these sorts of agreements. My background experience is mostly defined (or defiled) by the activities of the Spatial Design Expert Group in 2017–2018. These consisted in a push to find broad, cross-disciplinary support for preferring good spatial solutions, and a ‘stage’ on which a number of scenes were performed that, serious intentions and good faith notwithstanding, tended to fade into tragedy, comedy or both at the same time.

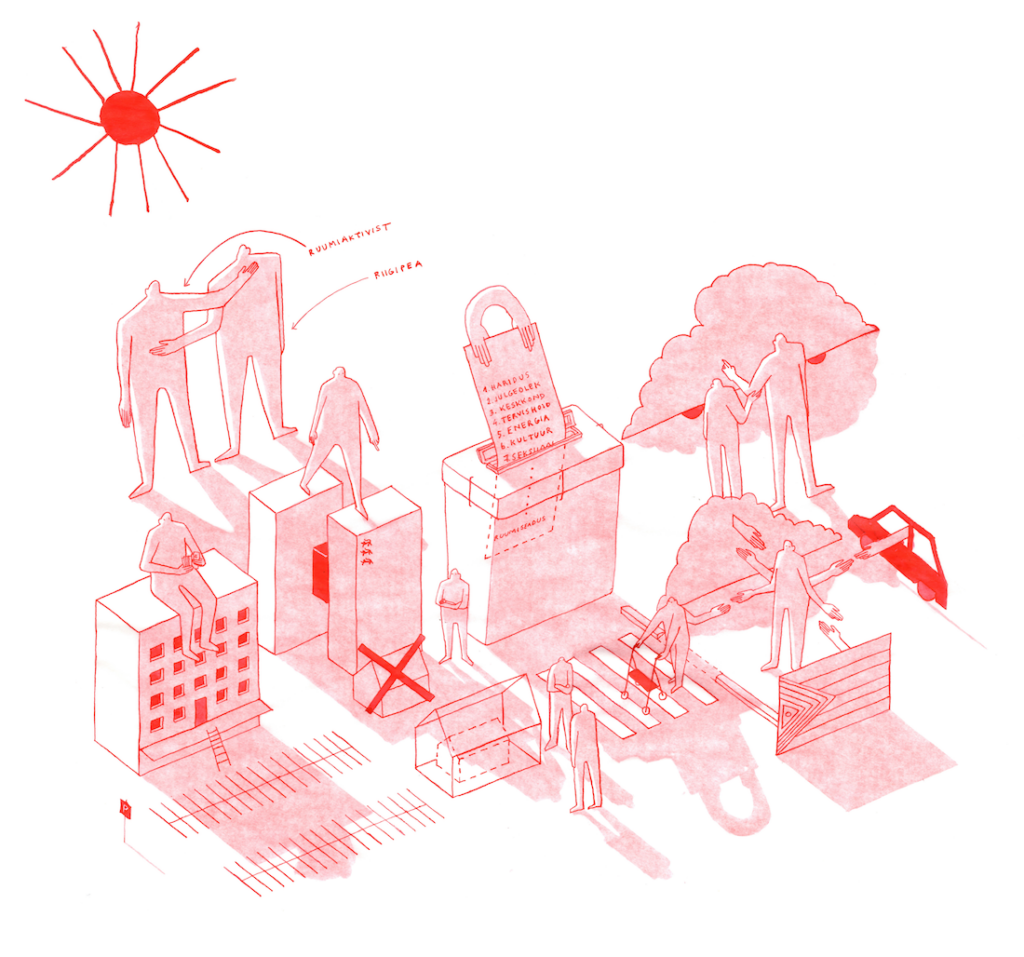

There is a number of agreements beyond or beside spatial design that are shared much more widely and deeply in the society than any spatial agreement could ever be. Democracy, capitalism, multiculturality and rule of law are four of them that I will be examining here. Naturally, there are others. Some debatable variations on this topic have loomed only in retrospect, so let us describe namely these. Note that for the purposes of illustration, some of the following lines of thought can get somewhat cartoonish.

Different agreements

As it was said, every social agreement can obtain only in a framework determined by others of its kind. At the same time, each agreement in its self-standingness tries to be an independent arbiter in most social matters. On a closer look, each of them can be narrowed down, all the way up to renouncing them. This is the peculiarity of agreements. Natural laws tend to function in a different way, but no social agreement belongs among the latter.

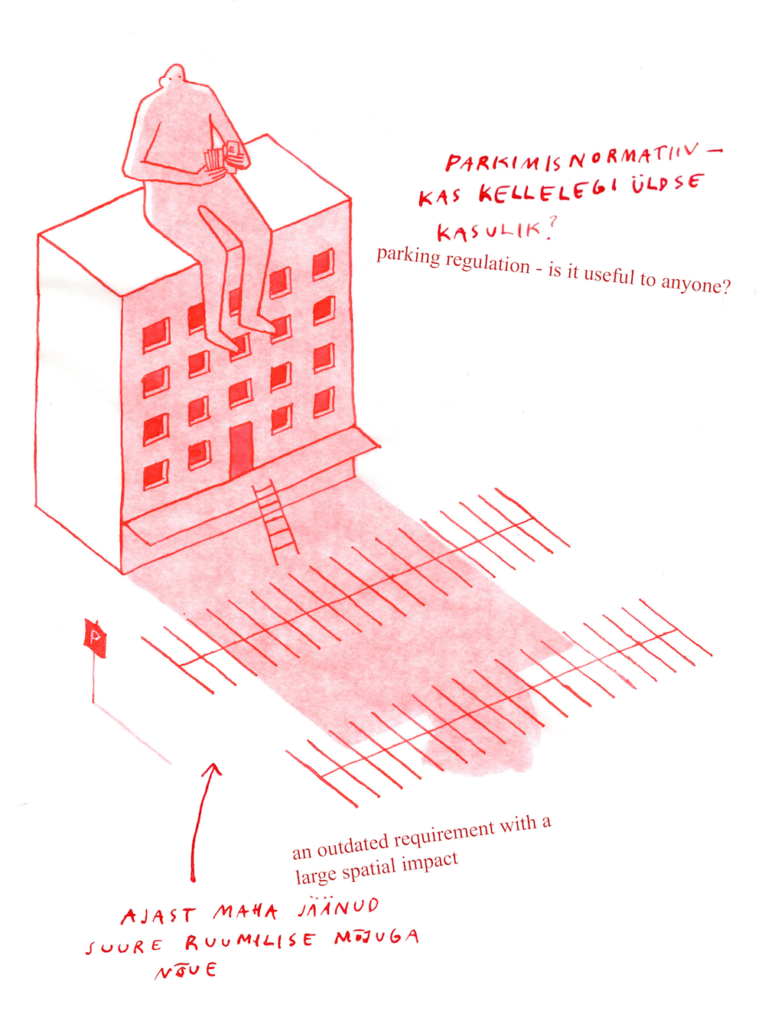

Capitalism is such an immanent presence in our view of the world that most of the time, we do not question any of its principles. Private property, business law and law of obligations tend to structure our perspectives on all walks of life. Speaking of spatial quality, it is obvious that we cannot expect anything from private real estate developers that would not be beneficial for them. Much of our spatial design results from private initiatives—housing construction, office spaces and commercial buildings are first and foremost subject to the rules of capitalism. Spatial quality can also be discussed in terms of return on equity—if the latter light starts to dim, then the question of high-quality space falls into oblivion. We might want to put it into law that only good spatial solutions can be made, but as long as this is complemented by a profitability condition, we might as well refrain from laying down the former.

Yet, capitalism can sometimes pull the cart of good spatial design even without any statutory obligations. If the developer gets a whiff of good sales potential with a good solution, and the spreadsheet calculation happens to be favourable, then private capital can bring forth surprisingly good urban planning or architectural ensembles.

Rule of law is, simply put, the principle that social order stems from certain agreed-upon rules, which are enforced by certain institutions and persons determined by the agreements. Our present rule of law operates in the conditions of constant legislation, meaning that it is an inherent part of the system that rules of the game keep changing—we have ministries that keep drawing up regulations and their amendments, and a parliament enacting these rules. Any currently operative system always has supporters and opponents, and every proposal to change the rules is met with both resistance and warm welcomes. Redrawing the fields of decision-making is a painful process, for some will lose and others will gain something, and this creates friction in the society.

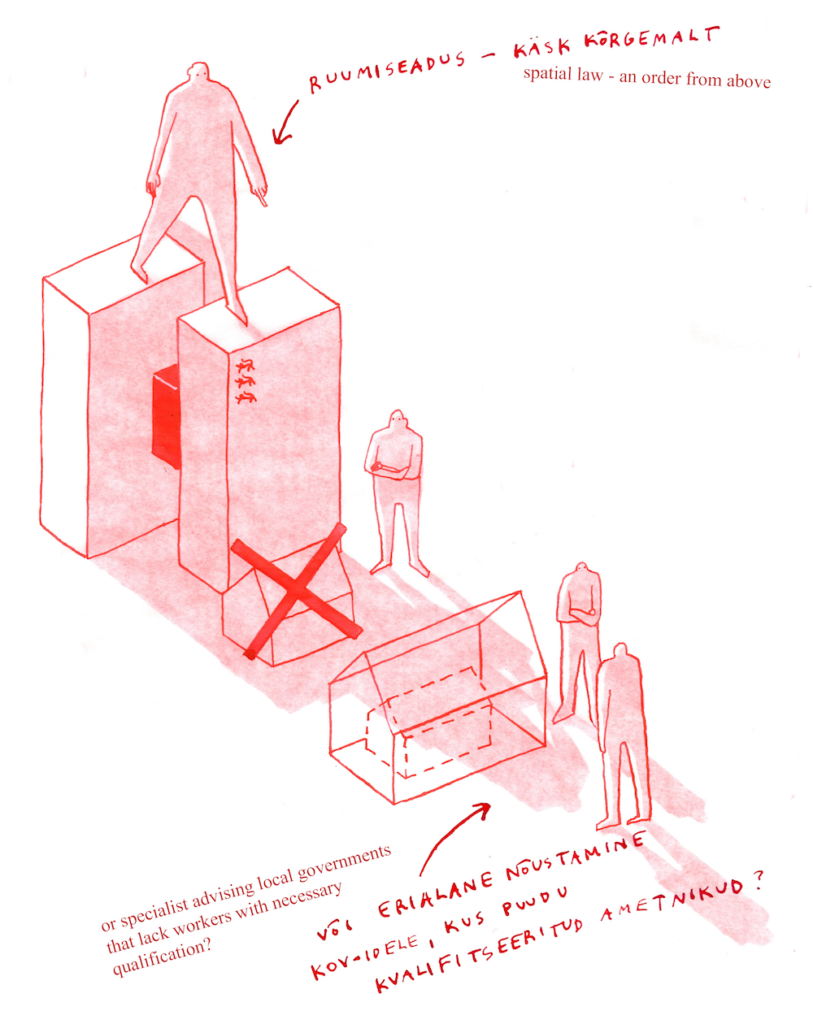

Tensions rose from a proposal by the Spatial Design Expert Group to give the state some sort of advisory or supervisory role in important decisions concerning spatial quality. According to the current rules, decision-making on spatial design is divided between several social bodies, and in practice, this system works. The largest role is given to municipal authorities who enact general and detail plans, and issue building permits. If we were to say now that henceforth, these powers of the municipality can be administered or controlled from another level, then the representative of the municipality would, with one hand on the law book, kindly refuse. The current legislation supports this, because agreed-upon rules have their own inertia that helps to maintain and preserve them.

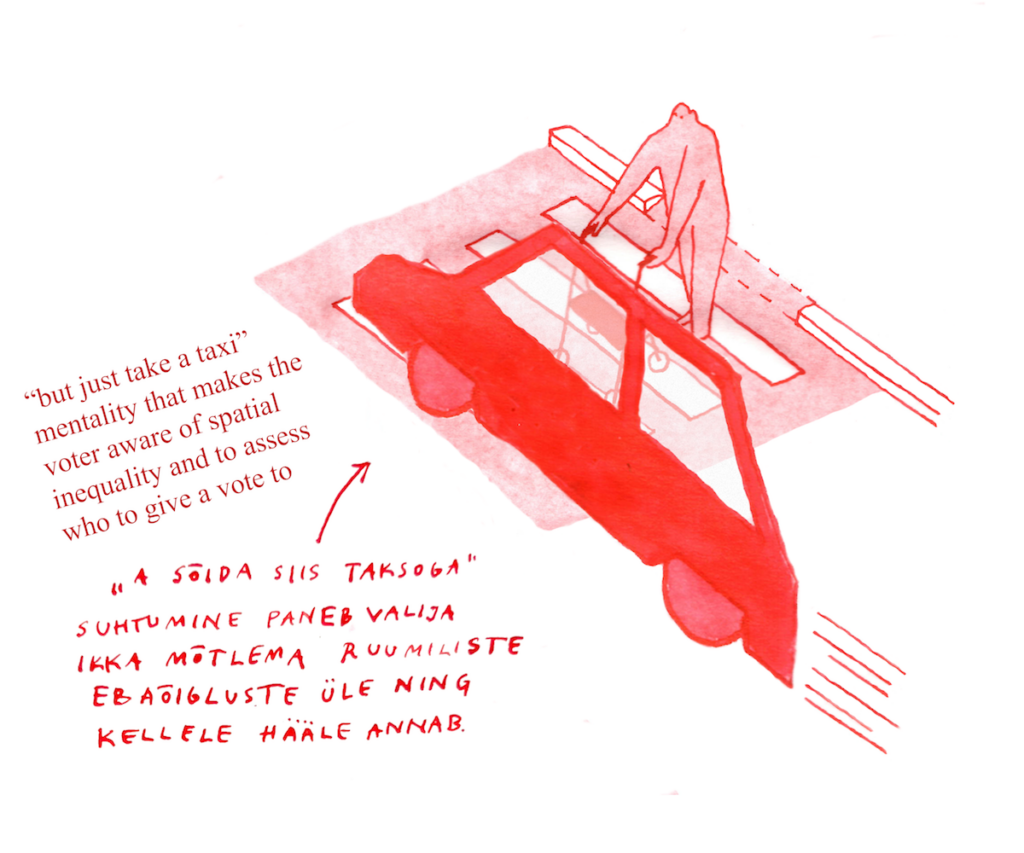

This is where democracy, another indisputable pillar of our contemporary society, enters the discussion. If the majority in the society so desires, then rules can be changed. Unfortunately, the majority in the society does not care much about the quality of spatial solutions. You disagree? Set it against issues like living standard, security, healthcare, education or rights of sexual minorities and look again. So, if there happens to be someone in the municipal government who obstructs the reorganisation of spatial design, it will be difficult to muster enough forces to break this resistance. It is difficult to get any traction for the architects’ desire to help the society in these matters. But democratic society also has a back door. Representative democracy is a form of exercising the power of the people where the will of the majority is expressed and implemented by an elected minority. Even if the crowd is uncooperative, it should still be possible to work with the representatives.

But now we reach a curious paradox. Representatives are easier to negotiate with on issues that are of little interest to the society that they represent. But where the general society is interested, it reacts, and the discussion tends to go public. For the most part, though, the spawn of capitalism and democracy still operates in the back corner of the back room, where opaque deals between politicians and entrepreneurs are made, and this Trojan horse can give birth to high-quality spatial solutions aswell. If spatial designers could reach an agreement with the people’s representatives that the quality of spatial solutions is important, then this idea could also take flight at the level of the state. On the initiative of the Union of Estonian Architects, this door has been rattled for years—the progress is slow, but it would seem there indeed is some. The fact that there are a few representatives with spatial education has also eased the path a bit, and the fact that their number is growing gives hope for the future. Thus, a spokesperson of the union could go to a dinner with a minister and, in a friendly atmosphere of mutual understanding, reach an agreement that spatial solutions really do enable to change people’s lives for the better.

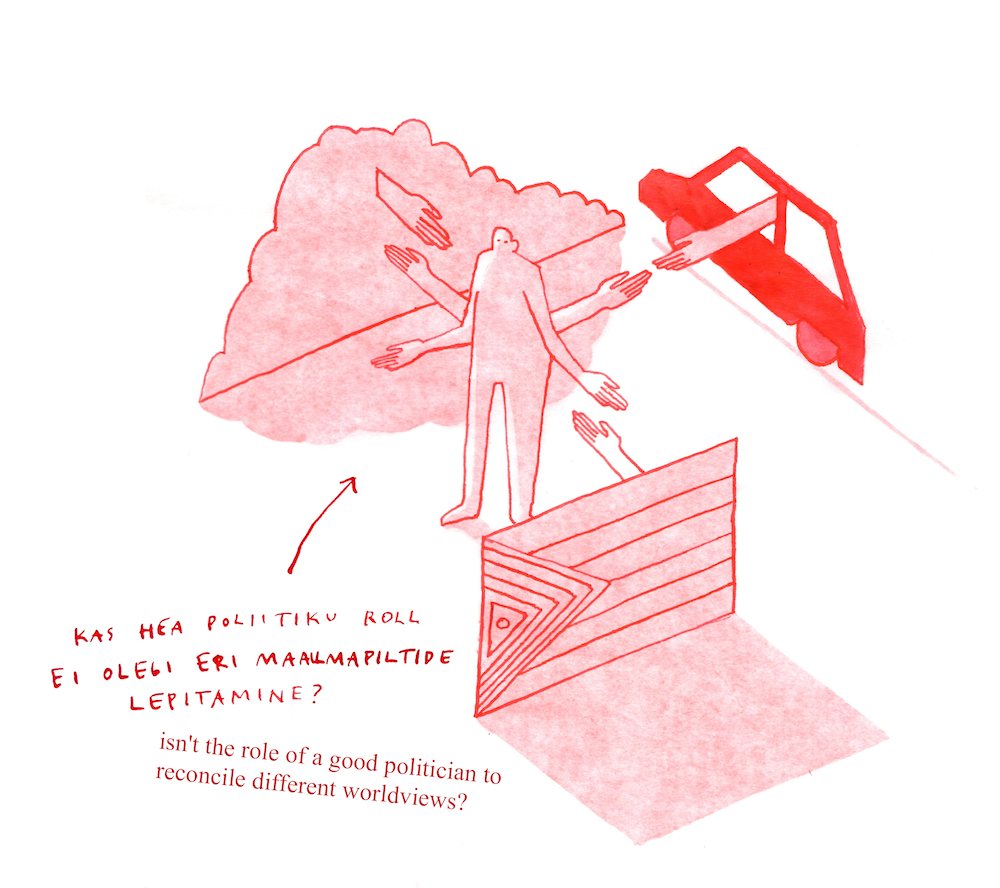

At the next moment, multiculturality mixes everything up again. What is understood as a good spatial solution varies. Country- and city-folk, people of different ethnic backgrounds, age groups and subcultures, people with different habits and customs—all of them are voters. What if something that is good for one is bad for another? And if I as a politician have to take responsibility for a decision that leads to implementing that bad solution, who is going to vote for me the next time around? Thus, a representative might seem like an easy catch during a dinner—but even when left on their own, politicians are never alone. The voices of voters return to haunt them in their heads, and any clarity that was just a moment before dissipates. A part is also played by political advisors who, regardless of having attended that dinner or not, constitute an ideological and political compass that points most reliably in the right direction. In that case, it is easier to rely on the current law, capitalism, democracy, and carry on forthrightly with the previous agenda.

So is it all bad, then?

And thus, the requirement to prefer good spatial solutions tends to not make it into laws. This is not unequivocally bad (said the fox about the grapes). After all, architects have already agreed among themselves to do only good spatial solutions anyway. This is even a sort of architects’ Hippocratic Oath—without it, there would be little point in having architects at all. Yet, we all know how the solutions of some other architect can often be inadequate or even silly. By now, the role of municipal architect in the procedure of building permit issuance has diminished into compliance checking, a task that could indeed be handed over to artificial intelligence at some point. Yet, if the specialist was given a further task of assessing the quality of space, and happened to comment that the quality of space is poor, how exactly should this be taken into account in processing a construction project?

The character of a good spatial solution is conditional. Agreeing on the criteria for a good spatial solution is possible on the level of abstract parameters. There is a number of functional, ecological, aesthetic, economic and social aspects that can reflect a certain solution. This sort of measurement system helps to rule out subpar solutions, but each concrete case presents a more complex situation. First, the balance between the components in a particular solution is always different, and thus, assessment is not particularly unequivocal and objective. Furthermore, architecture does not always want to fit in such categories, and sometimes there can be a boom in a sector that has not been described beforehand. Very well—we could also give a separate assessment for an unexpected conceptual component, but this makes comparisons more difficult.

In other words—assessing a spatial solution as good or bad is a discretionary decision that requires categories, an ability to understand and weigh them, and a mechanism that would give a force of legitimacy to the decision. So let us suppose that the specialist decides, and the official mandate is a means of sealing the decision. If the goodness of spatial solutions is thus turned into a legal obligation, then any disagreements are going to be resolved above the level of spatial design specialists—i.e., in court—and this time around, the assessment will be done by lawyers. And then we will be forced to ask—is this the kind of spatial design we wanted?

I would like to conclude by expressing frivolous optimism in two regards.

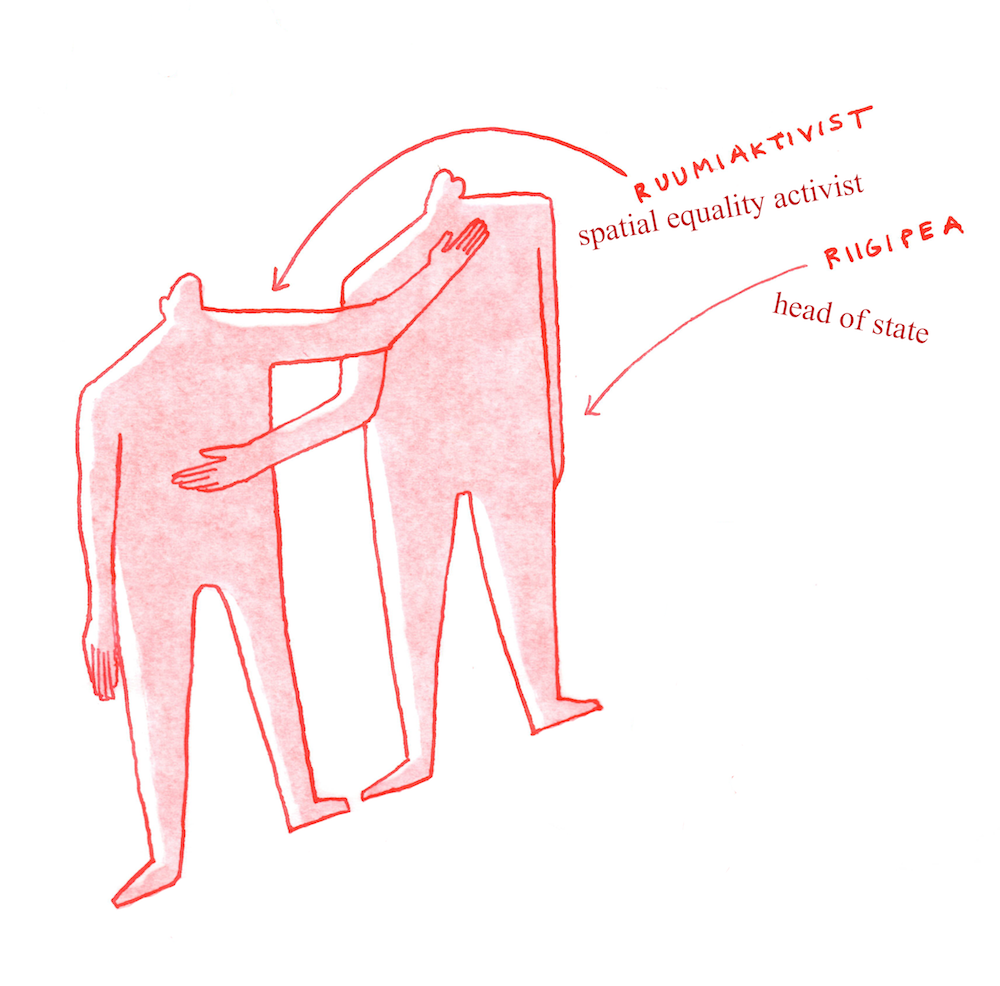

First, Estonia is a small country and here, every important issue is reduced to the personal level. Institutional agreements are born only in case of compatibility between the persons involved, while grudges and enmity can let the air out of even the clearest and commonly intelligible useful ideas. In other words, under certain contingencies, some future prime minister might end up having a deskmate from school days who has since profiled herself as a spatial activist. This could lead to steps that help to implement at least half of the basic plan described above, and the fading away or persistence of our people could play out in a better spatial environment.

Second, I would like to suggest that, in general, the current order does not preclude good spatial solutions.

INDREK RÜNKLA works at Kadarik Tüür Architects. He has taught at the Estonian Academy of Arts, worked at Alver Architects and held the position of Adviser for Architecture and Design at the Ministry of Culture.

ILLUSTRATIONS by Ulla Alla

PUBLISHED: Maja 111 (winter 2023) with main topic Street Unrest