Kaja Pae: Which building or architectural project has seemed the most enigmatic to you? In this way, remained somewhat inexplicable, yet spoken to you through time? What is it about a building that enables us to say, “Architecture is an art of space“?

MARGIT MUTSO

Architect

When a building touches me, haunts me, when there is something beautiful about it, some kind of poetry that cannot be fully explained, then this is what I would call art. Three-dimensional art, art in space, spatial art.

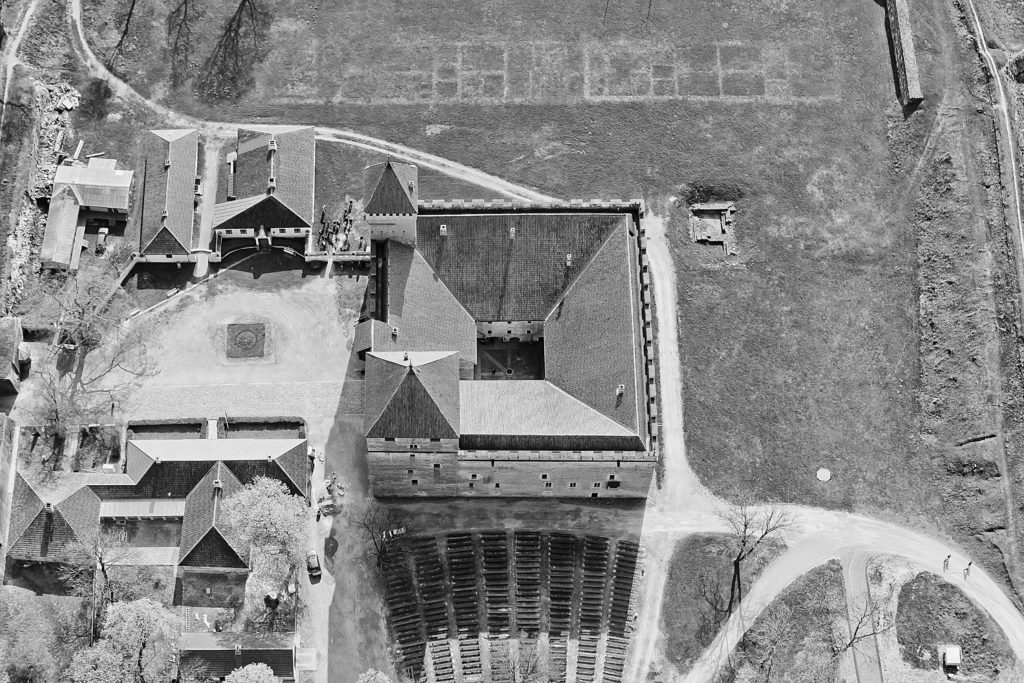

If a building was completed more than a century ago, it is sure to enchant me. The older the building, the more riddling the effect – time adds layers upon layers to spaces and facades. One of the most powerful edifices in Estonia is undoubtedly Kuressaare Castle, which I remember from when I was a young child: a mighty and impressive stone body, whose walls are so thick that they can fit stairs and passages inside them, a labyrinthine layout where you can wander and get lost, oozing a specific scent, mystically reverberating arched rooms with a function that is as difficult to guess as the source of the slightly eery yet exciting air that fills them, unexpected apertures with unfolding views of the island’s nature and rooftops of the city of Kuressaare. You may try to unravel the mystique, make sense of the plan, study the historical records, but the allure of the castle remains. It is so powerful that it entices you even through photo or film.

I have come across some new buildings with a mysterious metaphysical effect that still haunts me years later. In most cases these buildings are tied to the surrounding nature and/or some special purpose, something you cannot really put your finger on but can sense in the architecture. For example, the Kakamigahara Crematorium in Gifu, Japan (by architect Toyo Ito) with an undulating white concrete roof appears as a vibration between a mountain and water, encapsulating the last remains of the deceased and the sentiments of those closest to them, while reflecting back the Japanese philosophy of death.

MARTIN MELIORANSKI

Arhitekt

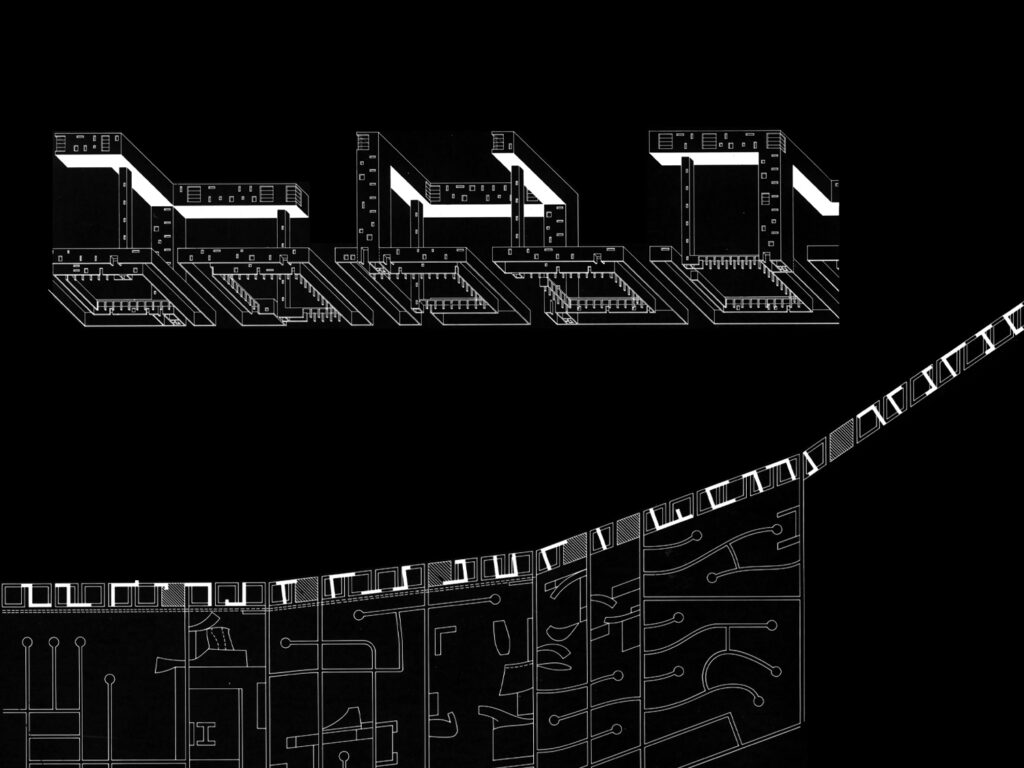

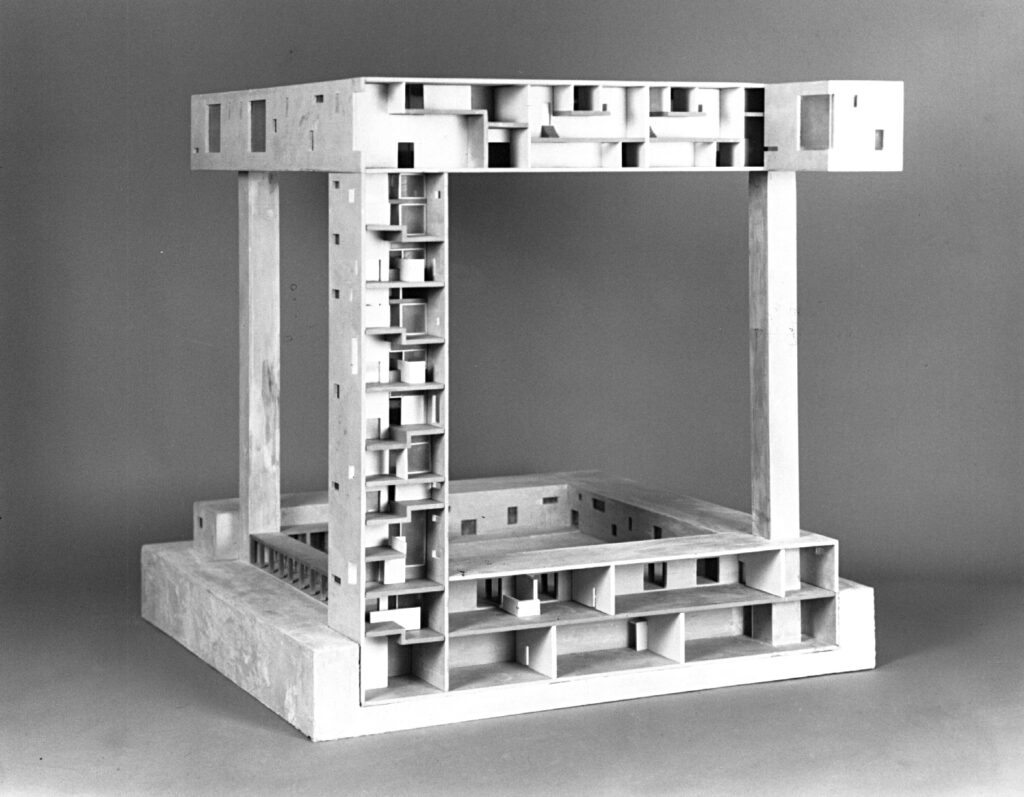

It is a delight to rediscover certain projects that are often unbuilt, but somehow resurface after a few decades of their conception. The immediate architectural impact1 that the conceptual and spatial integrity inherent in these projects has on the viewer does not fade with time, but grows and amplifies instead. In my opinion, one of the most important examples from this lineage is the “Spatial Retaining Bars“ project of volumetric elements that the American architect Steven Holl envisioned on the edge between desert and city in Phoenix, Arizona, in 1989. The objective of the project was to confront the diffuseness and stop the urban sprawl by consolidating suburban residents. Holl’s work was inspired by the remains of a canal system originating from the Hohokam Indians’ civilisation2 that vanished about 500 years ago. The buildings he designed incorporate both the discreteness and timelessness of Modernist thought – the project is a sequence of spatial structures whose physicality is animated by a chain of functions covering residential, industrial, public and cultural institutions.

HELMI LANGSEPP

2019 graduate of the architecture department at Estonian Academy of Arts

I made a conscious decision to visit the memorial for the victims of communism at Maarjamäe late at night or early morning. From the main entrance to the memorial, the space seems simple and legible: a ramp a couple metres wide, surrounded by two black plated walls.

Yet, a space shift occurs when you enter the passage. On the one hand, the side walls appear incredibly steep, on the other, the whole composition feels miniature and it seems like you can simply step over the walls. A sense of infinity spreads throughout a very small and a very large space. It keeps the space from dissolving. The binary perception of wall height could be explained by two interlacing views: a view of the sky when looking straight up from between the walls as a large dimension, and the discernible end point of the passage in the greenery, where the walls seem to be flat with the ground, as the small dimension.

The passway between the walls makes you simultaneously aware of the presence of two opposites, the large and the small. Sensing both extremes is in constant flux and in relation to the person inside the space. For me, the significance of spatial art expresses itself as a direct experience of being inside a space, as a relationship between the space and the person in it. In other words, the scale shift translates to a shift within myself.

At one point, you have come to the end of the passage and looking back upon it you are not quite able to discern the size of the space that you just passed. There is an alternative way back to the beginning by the side of the wall. The part of the wall reaching the ground outside the passage is reassuringly mediocre in height, causing no trace of a shift. The visitor may pleasantly drift away once again.

VELJO KAASIK

Architect, professor emeritus at Estonian Academy of Arts

I have at home an old issue of Arkitektur, the journal of the Swedish architects’ association, from December, 1991. There is a photograph in it of a Catholic monastery located in Tomelilla, Sweden, that was designed by a Benedictine monk and architect Hans van der Laan. It is not my kind of architecture, not special in any way. But from time to time I have browsed the journal, a bit embarrassed to show my interest. A young Estonian documentary artist recently had a show at the Estonian Museum of Contemporary Art about a monastery by van der Laan in Roosenberg, Belgium. I am not ashamed to write down these lines after that.

*

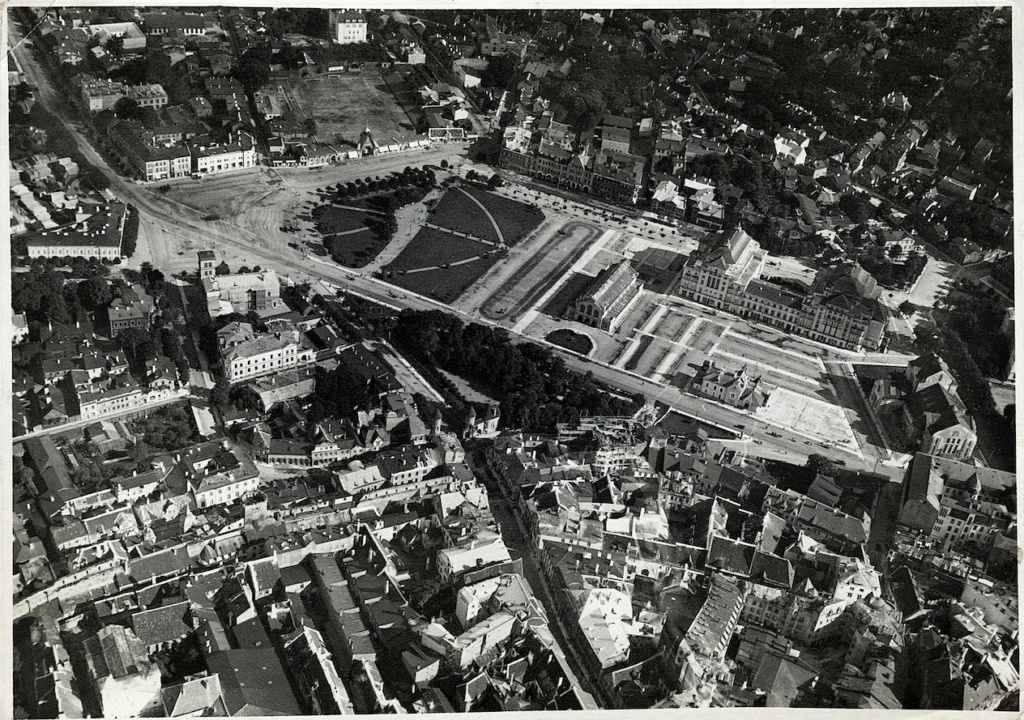

In 1944, I was six years old, and there was a toy store in the Urla building (the current kids’ department store building) that my mother took me to on occasion. On our way out of the building, I would see the Drama Theatre, “Estonia“ concert hall and the market building across the street. “Estonia“ and the department store were both damaged during the war, but they only restored “Estonia“. Sometimes, I still see the missing object – the department store. When a limb is amputated, a person sometimes feels phantom pain. I experience a similar phantom pain about objects lost in space.

*

In Tallinn, I have discovered a new, exciting urban district in the spirit of complexity and contradiction. I visit this place from time to time. But I have no photo material to prove its existence, at least not until I find it in reality.

KRISTEL NIISUKE

Architect

A lady on a second floor balcony of a panel house is yelling at me – I parked my car across a line. I am trying to apologise, and repark my car. No use, the damage is already done. I abandon the crime scene, jump across the street and shuffle through a scrub. I come across a garden with closed gates. I try to find a corner where I am hidden from the lady’s sight, and I climb over the fence. Here it is now, in front of me, the place I have read and heard so much about, seen pictures of in old books. Here it is, the lost city of Z, the garden for lost children.

The design principle of the extension to the kindergarten “Piilupesa“ (“Hideout”) of the Kirov fisherman collective farm, designed by Ado and Niina Eigi between 1981 – 1983, is based on reflections. The gradatory facade, cantilevered window surfaces, repetitive mirror reflections of the gable-like skylight create a structure, that is complicated enough to not give itself away immediately, but also archetypal enough to enable a person invested in it to crack the code. Oh, right! Now I get it – we are dealing with an architectural manifestation of the super-popular Rubik’s Cube (a toy discovered by mathematician Erno Rubik, first presented in 1981). I am taking shots with my phone, simultaneously reflecting and twisting the kindergarten back and forth in my mind, creating new structures and shapes.

Two weeks later I read from a newspaper that the buildings of the former “Piilupesa“ kindergarten, which has stood unused for decades, will be crashed to make room for a new development project.

Kindergarten “Piilupesa“ of the Kirov fisherman collective farm in Haabneeme, architects Niina and Ado Eigi, 1983, the building was demolished in 2017.

VILEN KÜNNAPU

Architect, professor at TTK University of Applied Sciences

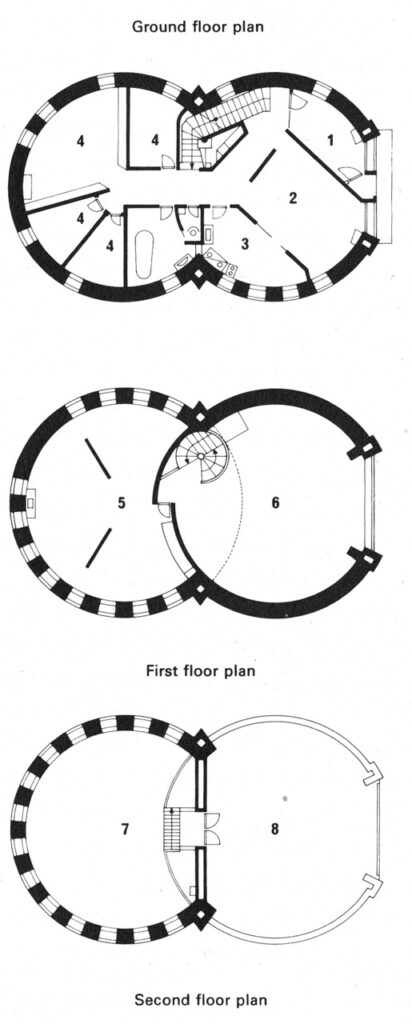

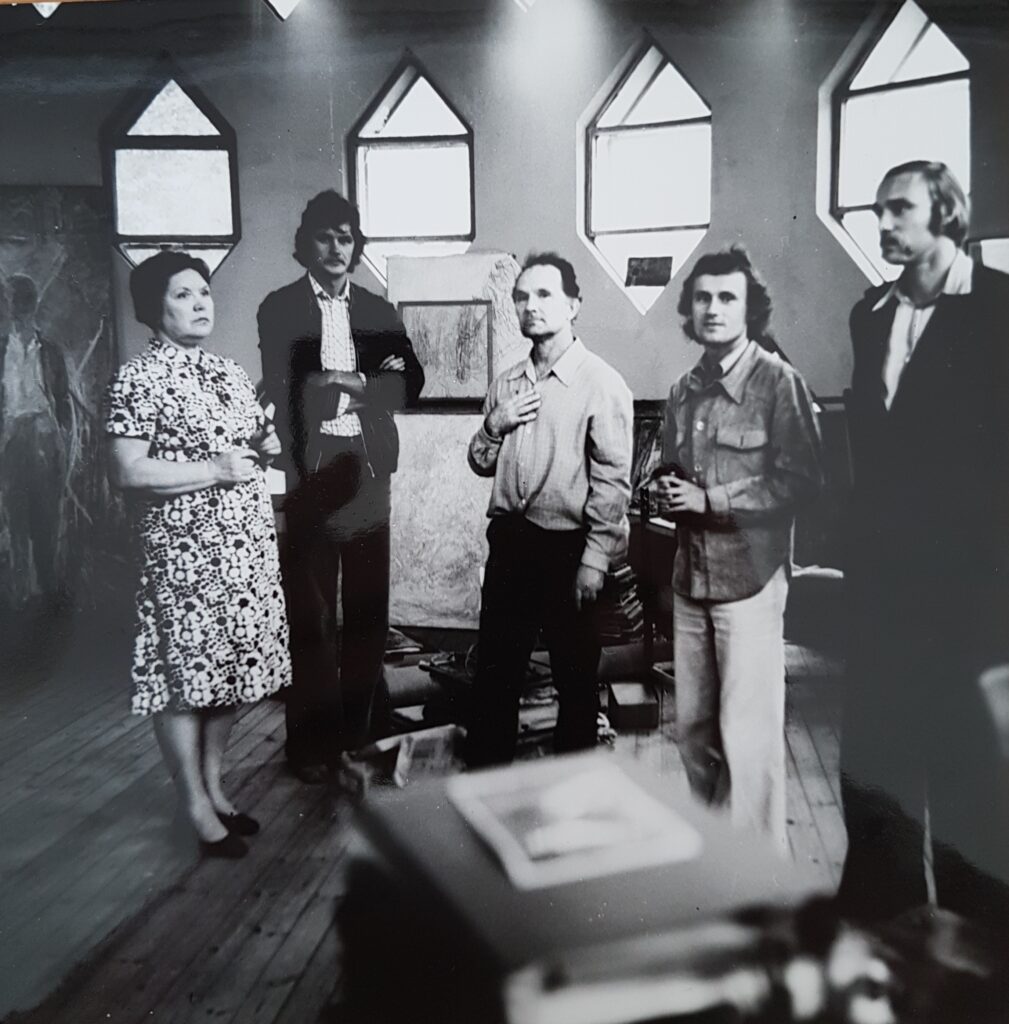

There are many famous buildings in the world, but a limited number of those that truly speak to you. The latter are free of slyness, postures and slickness; these are buildings carried by passion, risk and mysticism. One of such houses is the private home of Konstantin Melnikov in Moscow. I visited that place in the mid 1970s with EKE Project architects Ülevi Eljand and Rein Tomingas, and photographer Jüri Varus. Old Melnikov had passed away, and so we were greeted by his painter son and the latter’s wife.

I was astounded by the power of the house. Located in downtown Moscow, adjacent to big and huge Neoclassicist dwellings, this tiny work of art appeared a mighty and radiant secret chamber. Two intersecting cylinders in the layout and around one hundred hexagonal windows on the facade composed an unforgettable architectural sculpture. The external simplicity was counteracted by a complicated and mysterious interior with a magical spatial effect. Melnikov’s son talked to us about the house and his father and suddenly burst into tears. The tension was palpable, I think I myself cried a little, and then, right there, a secret pact was signed between myself and eternity that I carry along with me to this day.

HEADER: Kindergarten “Piilupesa” of the Kirov fisherman collective farm in Haabneeme, architects Niina and Ado Eigi, 1983, the building was demolished in 2017. Photo by Tõnu Tunnel

PUBLISHED: Maja 97 (summer 2019) with main topic Architecture is an Art of Space