Interviewed by Katrin Koov

First off, to refresh our memory– how and when did you join the project?

Tomo: After winning the competition, the architects from Dorell Ghotmeh Tane (DGT) visited Estonia very frequently to show their sketches , but the museum didn’t have full confidence in them in that first year and the architects themselves realized they wouldn’t get by without a local partner. I think it was in late 2007 when Villem Tomiste invited me to an Old Town restaurant to meet DGT. Afterwards, DGT got in touch again and said they were looking for local partners to develop their design for the Estonian National Museum and they said they’d talked to several practices.

Hanno: In parallel, the museum was also looking for architects. We were recommended to Krista Aru , but DGT ultimately was the one who made the decision. It took a year until signing the contract. At first, the museum felt that the project should be carried out by someone else, in any case a local team of architects, not DGT themselves – because DGT didn’t have actual experience doing design development for their initial designs, let alone in a foreign country.

Was DGT’s decision perhaps influenced by the fact that your office is “international,” as it were – it was easier to understand each other?

Hanno: I think so. Tomo and I both have experience working in the States. Plus, ten people from outside Estonia have worked at our office, and that gaveconfidence that there won’t be a language problem. We had to do the design development process in two languages (until the end of the first construction documentation stage).

Tomo: Fortunately, I had experience working on big projects and thus I had an idea of how it should work. Working for Rafael Viñoly in the US, I was involved in a megaproject – developing the design for the 140,000 m2 Pittsburgh Convention Center. I got an idea of what it was like working in a large team, the division of roles and project structure.

How did you divide the work assignments and create a scope of work?

Hanno: There was a clear scope of work. In the preliminary design stage, we were responsible for getting approavals from the authoritiesi.e. local goverments and fire department and on. They prepared the basic drawings; we provided consultation. In the design development stage, we dealt with specifications of doors and windows, and drafting up the interior solutions. We also provided consultation to DGT with regard to local construction materials and suppliers. Our task was also to monitor the budget – making sure that great art could be executed within the constraints of the budget.

Tomo: A large and complicated part of the work was intermediating the architecture and engineering parts – negotiations, interpretations and translations.

Hanno: DGT’s architects had previously worked in large offices and their attitude in the beginning was that they’re the ones who come here and tell us how things will be. But there’s a different climate here, and for another thing, different laws, and third, different relationships in the field of construction. In France, the architect is always the general contractor, but here the tenets of the Public Procurement Act had to be followed. The position of the architect on the team is different. Furthermore, the engineers for this prestigious showpiece building had been chosen at tender for the lowest cost, and this caused problems of its own.

Didn’t a creative conflict arise for you – the fact that you had to help to realize the work of different authors?

Tomo: It did for me, at first. But I had to get straight what benefit we would derive for our own practice. I realized that we could experiment with new construction methods, new products, collaborate with new people. And, this was during the recession and we had more time to devote to it. When I spent more time on the project I started understanding what this project is all about. A dynamics developed in cooperation with engineers and architects, and I started liking it.

Hanno: In the construction documentation stage, we were already responsible for the entire project.

Tomo: The first procurement for construction with construction documentation set prepared by DGT fell through. Then we had to take over the project to organize for the second construction procurement. The whole structure of the project had to be redone.

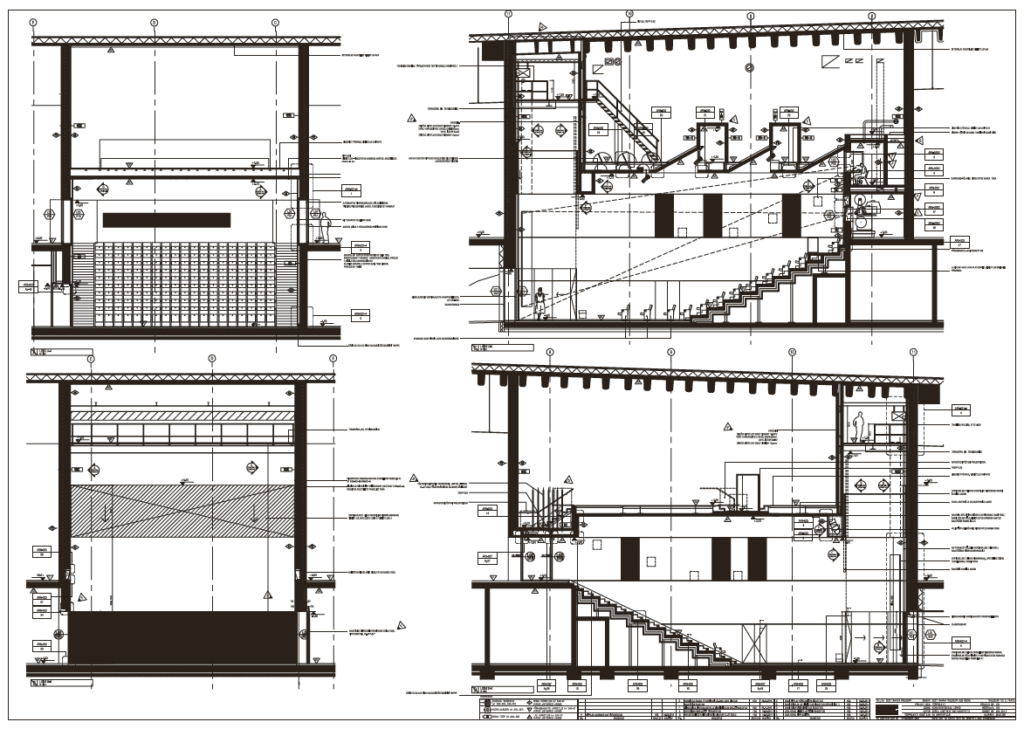

Hanno: The drawing methods, the system of references and the hierarchical system of the drawings were different. Everything had to be redone from scratch. They had a six-level structure of drawings withoutcross-references. We restructured the documentation into three-level system with necessary cross-references.

Tomo: The difference between French and Estonian systems emerged – the extent of the architect’s responsibility. In Estonia, the architect also gives details to the engineer how allthe systemscome together.

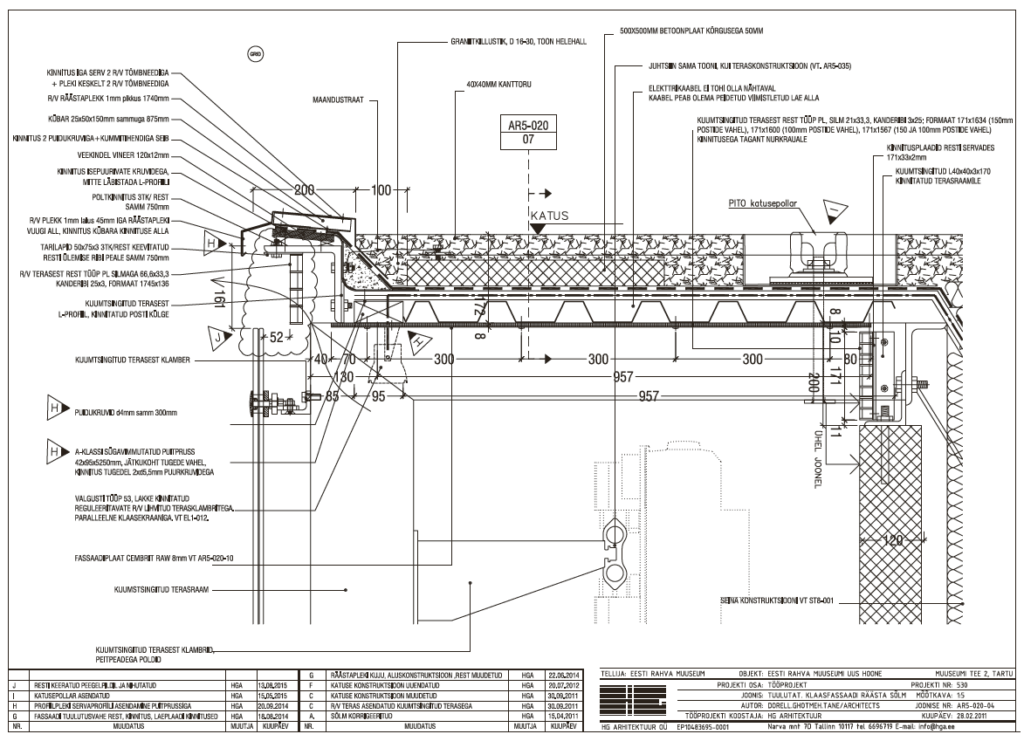

Hanno: This was a major learning as well as teaching project. For instance, French architects don’t know anything about cold bridges and condensation, we had to explain the problem to them.

Tomo: Actually, I wasn’t familiar with the problem of cold bridges before I came to Estonia. I have heard of the term “thermal bridge” in the US – or “heat bridge”, rather – but not “cold bridge”: Different things are important in different places.

Was it helpful to have a Japanese architect on both teams?

Tomo: Maybe… But we always communicated in English. Now that the building is completed, I talk to him in Japanese as well.

Hanno: I think your personalities complemented each other very well. Especially if some conflict situation arose, the Japanese could discuss the matter calmly amongst themselves. The others couldn’t; things got heated. The cultural difference came to light in this regard, for sure.

Tomo: Dan sometimes got quite heated (though maybe this was his tactic in negotiations), Lina was more rational, Tsuyoshi remained calm. Negotiations were always two-tiered – one level was at the table and the other in the hallway. Sometimes the fact that we took decisions without their permission caused conflicts. These were questions that had to get answers quickly.

Hanno: Although we were their subcontractors who were supposed to representtheir interests, we still had to take into account who was the end user and act in the interests of the whole undertaking.

How did you work together? How often did you meet and what channels did you use tocommunicate?

Hanno: At the beginning, we agreed that we would draw up a report on developments weekly, but it turned out that was pointlessly time-consuming. Especially when we started discussing how to do thing, the discussion became many times longer than would have been necessary. What worked was giving them a clear-cut choice between two options.

Tomo: We had meetings every week with engineers; DGT took part every other week or once a month. We had to send them the minutes of the interim meetings and we saw that we weren’t able to translate everything down to the last detail and ask for consent for everything. In the beginning, we prepared minutes a few times, but we realized immediately it wasn’t that effective.

Hanno: Then we said that if our goal is to get the project done in time, you have to trust us.

Tomo: Of course, DGT would have preferred to check everything a lot more, and I understand that, because the project was a very important “baby” for them. But we saw that we needed to take reality into account a lot more. Krista Aru, the director of the museum at that timealso said we had to help them a little more, otherwise the museum would never be completed.

For example, we proposed that the loading area could be moved up to the ground floor and that suited the client, but then we had to serve up the proposal as if the solution had come from DGT. Urmas (who was the architect on the EA Reng side) and I travelled to Paris and we sat down with DGT for three days until we reached a solution as to what it could be like.

What else changed in comparison to the competition entry?

Hanno: Compared to the schematic design, the general concept is the same, but as regards the extent to which the design was refined, it is a totally different building. In the competition entry, the house was conceived as being completely covered with glass. Now it is a concrete building partly covered with glass. The competition entry envisioned the interior walls as massive load-bering walls – all made of concrete. Now they are steel-framed walls installed around concrete columns. The logistics of the storage areas on the basement level were totally changed. The basement was raised higher than the water line. The roof was originally a expanse of concrete where people could walk on, but that would have meant that the entire structure right down to the foundation would have had to be more robust. As a concept, it would have been cool, but such a building would not have been built for the budget. Also, I don’t know how much it would have been used in practice – there’s no lack of space around.

Tomo: It was a major decision to close the roof for access. The client had to fly to Paris and explain to DGT directly that was the solution we would go with to stay in budget. All the big decisions were made tete-a-tete and the client had to lay it out as an ultimatum.

Many times, the museum reached a point where they were ready to scrap the contract with DGT, but it didn’t keep the architects from continuing to develop the design. They had a strong drive. It’s a good example of how an architect needs a lot of patience, and faith in themselves and their design in order to implement a work.

Hanno: It’s a shame, of course, that you don’t see that great view opening up on the city centre. The site is actually at a higher elevation than Toomemägi Hill [on the other side of the river]. When Tartu was besieged in the Middle Ages, this was the vantage point for the commanders. In the Soviet era, Raadi airfield was also the airfield with the lowest frequency of fog. The site is high but you don’t see that fact on location.

A big achievement was the fact that the roof is completely free and clear – not a single chimney, pipe, antenna, barrier and so on.

When you look at the museum building from a distance, how would you describe it?

Hanno: I think it’s a very future-oriented museum. Often with these projects, a building that fulfils the basic minimum needs ends up being built, but here there’s also great potential for further development.

Tomo: The building’s load-bearing structures have a lifespan of 200 years. That’s extraordinary for Estonia.

Hanno: Because the building has a column and beam system, everything can be cleared out and the interior design reconfigured. We don’t know right now what the museum will be like in 50 or 100 years but I imagine that the building could house a museum in 100 years, too.

It seems to me, too, that they asked for a national museum, having some sort of vision of it, but they got much more. But what do you think about the exhibition?

Tomo: I have a few problems with it. They probably thought that the artefacts would not be strong enough by themselves, so they need a narrative background. The main idea behind the permanent exhibition – the timeline – is unfortunately not easy to perceive.

Hanno: There’s much background that isn’t actually the exhibit itself and doesn’t go well with the building itself, but tells its story. The result is a bit confusing, but on the other hand, it’s understandable they wanted to offer surprises, be something for everyone. The relationship between environment and exhibits seems best in place at the Finno-Ugric exhibition.

Tomo: The building architects should have been involved more in designing the permanent exhibition. DGT was very disappointed that they weren’t even showed the alternatives sent to the competition. Only when the construction already begun were they asked if they wanted to see them. Maybe the reason was the fact that the construction of the building passed to RKAS, State Real Estate Ltd, with whom we communicated, while the museum exhibition parts were handled by the museum itself in collaboration with the designers. It seems it didn’t occur to the museum that the exhibition part should be discussed with us or DGT.

What were you satisfied with in particular – or not satisfied with, as the case may be?

Tomo: I believe the construction quality could have been a lot better. It isn’t an ordinary warehouse building but a public building with a 200-year-long lifespan that needs more care. Maybe the construction procurement system should have been organized differently; for instance, not so that the lowest bid wins, but the tenderer who bids a medium price.

Hanno: We can be satisfied with our project in the sense that there were minimal changes during construction and the building remained within budget. Consider that the new buildings of Estonian Public Broadcasting, the Academy of Arts and the Tallinn City Government were all designed at the same time and went bust, but the Estonian National Museum project remained under control.

Tomo: When we were supposed to take over the project and add our title block, I felt it was such a Herculean task that we might as well just put a gun to our head. We had to operate in a very limited playing field and it was very hard, but I felt that if we don’t help out, another 100 years would go by before the museum is built. I thought: sure, I’m Japanese ,but I am a local architect, too, and I have to help carry out the idea.

Hanno: Especially since the end user wasn’t State Real Estate AS, but the entire Estonian people.

Tomo: Without a sense of mission, we wouldn’t have been able to see the project through to the end.

Anything – or anyone – you’d like to highlight additionally?

Hanno: Indrek Tärno was a very important person on this project. He was the consultant for the museum, who got the initial tasks together and later, he served as project manager for us, the local architects. He was completely abreast of every aspect and remembered everything. He’s a rational and balanced person and he’s got the architects’ and designers’ backs. Without him, construction supervision would’ve been very complicated.

Tomo: The collaboration between architects, interior architects, and landscape architects flowed very well. We marked that at the end of design process at a garden party at Indrek’s. We’re still in touch now.

In conclusion – could you sharesome statistics on the National Museum design process with readers ?

The building is 355.7 m long, 71.7 m wide and ranges between 2.4 and 15.3 m in height. The roof is a plane angled at a consistent 3.1% gradient. At the high end, the roof ends up with a 43.5 m long cantilever. In the middle, the building is in the air for a length of 40.7 m, like a bridge spanning a lower area where Raadi pond joins Lake Raadi.

The building was engineered with a lifespan of 100 years, the load-bearing structures have a lifespan of 200 years, the exterior walls 100 years, technical utility systems 50 years, exterior finishing 40 years, interior design 10 to 25 years, windows and exterior doors 40 years, joints 15 years.

Some specs: the building has 646 interior doors, 480 rooms, 80 interior wall types (excluding load-bearing wall types), 1,250 glass panels on the façade (glass screen).

As part of the initial task, we were given room spec sheets listing, on four A4 pages, all manner of requirements for each room. In total, over 1,000 pages of requirements for the rooms.

The glass screen has a pattern. One glass panel (3.5 x 1.75 m) has a total of about 22,000 images. There were eight different types of images sized about 1.6 x 1.6 cm, with a total random positioning. DGT created the design in the form of an image file, and the image had to remain constant. But the builder needed a vector file. The entire pattern thus had to be re-drawn. It took 40 hours of labour to redraw the pattern for one glass panel, resulting in an average speed of 10 images per minute. There were 10 panels with different pattern designs, which also had to be redrawn in the same way.

In the first construction documentation, the roof was to be covered with concrete panels measuring 1.4 x 1.4 m, and we made shape drawings of them, too. There were a total of nearly 10,000 panels, so about 1,000 panels in each shape.

The energy efficiency topic was dealt with extensively as well. Passive climate system in the storages, ground loop and hydronic heating, lights that turn off by themselves etc. I think the energy expenditure per square metre ended up being four times lower than at Kumu art museum.

The construction documentation took up about 3.5 m of shelf space.

HEADER photo by Takuji Shimmura

PUBLISHED: Maja 89-90 (summer 2017) with main topic Changing