Spectrum thinking has freed him from the constraints of the black-and-white view of the world: drifting in semitones allows him to choose only the topics that fire him up. Everything you start with must be finished, the process is facilitated by the main tool of concentration that to outsiders seems deceivingly chaotic.

Interviewed by Mirko Traks

INDREK PEIL is one of the architects of Kavakava. He graduated from the Department of Architecture and Urban Design of the Estonian Academy of Arts. He is also a co-founder of and architect at the office HEAD ARHITEKTID, architect at KAVAKAVA, supervisor and visiting reviewer at the Department of Architecture at EAA. A member of the Union of Estonian Architects. He has received the Annual Award of the Cultural Endowment of Estonia in Architecture and twice the State Cultural Award.

Is it correct to say that KavaKava is a platform for influencing space?

Platform is quite a good word, covering more than the office. The important thing is the independence that we have achieved. In other words, we can choose what we are interested in. There is also a clear continuity, something from the previous project is always transferred to the next one. Then again, the approach and topic may also be completely different.

Does the relatively small office KavaKava allow you to have a say in matters that are important to you?

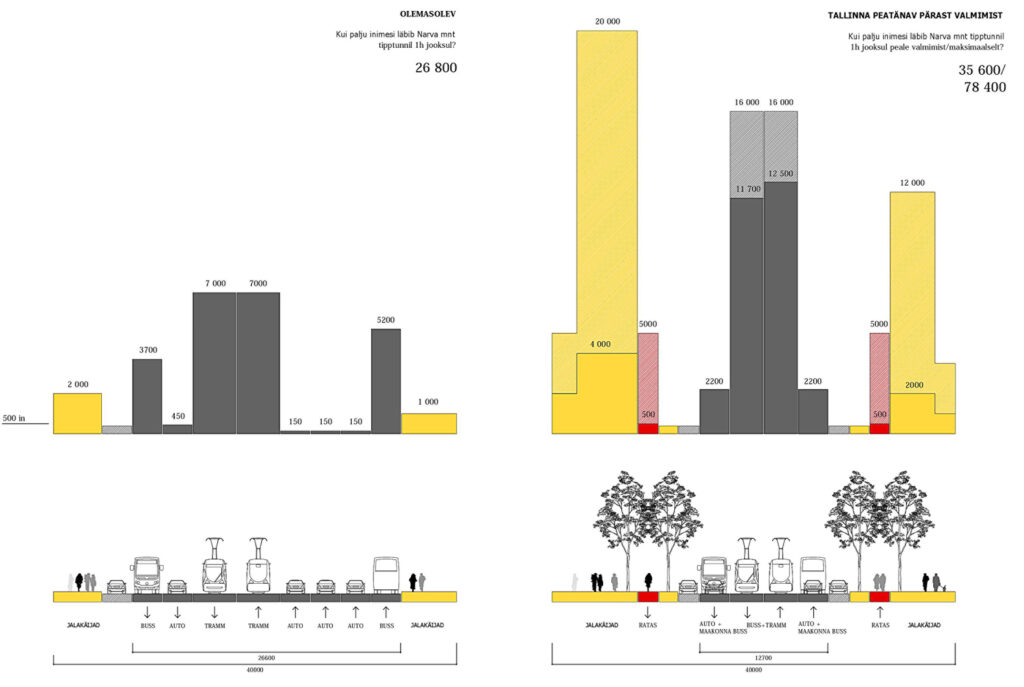

There are opportunities to have a say and also an impact, but the office could be indeed larger. We could immediately employ three more people. Our core people are the same but we often invite others to join in case of competitions. We have concentrated on the urban space for some years already, the projects of Tallinn Main Street and also Vana-Kalamaja Street are waiting their turn. Both are highly important works creating a new urban space and requiring thorough preparation. In connection with this, we have opened up also several new lines of work: the seafront vision and the Port of Tallinn masterplan competition. You cannot really find more interesting projects in Estonia. This year we started to participate also in building competitions again and teach at the Academy of Arts. We also take part in the research project of EAA “City Unfinished”.

Do you have specific criteria at KavaKava for choosing your projects in order to stand for the values that are important to you?

We certainly do. It all begins with selecting the competitions we want to participate in. Our interests have changed over the years but we also want to undertake projects with a wider meaning. For instance, the project “Great Public Space” within EV100 programme serves an important function despite receiving a lot of criticism. It brought many architects to the issue of public spaces. It boosts our inner motivation when the work has an additional dimension, for instance, good space reaching those people who usually tend to be left without it.

As the projects take thousands of working hours, we must be choosy, as later on you cannot make compromises in the quality, even if you kind of lose interest. That is why we consciously avoid flash-based work in competitions. The competition entry itself must be sufficiently versatile, primarily for ourselves, and include enough material and layers for further development.

You mentioned the project of Tallinn Main Street earlier. How do you manage such extensive projects?

We are used to working in and leading teams of 20-30 people. We usually have one or two large-scale projects at hand and then we do not take up new projects until the previous ones are in the construction stage. After the Creative Hub, I can safely say that we can manage any project that we embark on. It would be difficult to surprise us with challenges. In tricky situations, we are helped by the clarity of our ideas and the ability to distinguish the essential features. Longer projects allow more time to concentrate. In connection with the current Main Street project, we have thoroughly studied the topics related with the future of streets and the city, it’s like pursuing another academic degree. Our partners in the Main Street project include excellent local engineers, Danish lighting engineers and with Andres Sevtšuk also Harvard University. Similarly, we have cooperated with large offices. In the Port of Tallinn project, we partnered with Alejandro Zaera-Polo (AZPML).

Freedom should be planned in the city much like the density of connections and the variability of space. The appropriate new planning strategies need to be found. We have never talked about complete self-organisation in case of architecture. Looser order may actually mean more preliminary work or tests for the novel approach.

What is your so-called big agenda that is reflected in your work and civic participation?

I provisionally call it spectrum thinking. It is not perhaps an accurate phrase to describe it, but it means that I do not set things against one another. Intermediary forms between the opposites are sometimes more interesting. The content is better described by images, proportions, transitions, intermediary forms, contradictions, the potential difference, even yin and yang. This spectrum thinking is not the expression of any particular wisdom, instead the lack of some widely spread thinking disability.

It all begins with the way of thinking. Many of our planning norms and laws carry wrong and out-dated values opposing and differentiating the world unfoundedly. For instance, the indoor climate parameters require enormous technical systems to ensure precisely the same indoor climate all year round. The entire spectrum of the costs and impacts is not considered. The estranged and rigid understanding of comfort is actually subjective. The user experience is standardised. A new-built is outmoded before its completion but it has its so-called certificate. Urban traffic in Estonia is still governed by the 20th century mentality. Can you imagine that they are planning an amendment to the Traffic Law in 2019 stipulating that pedestrians can cross the street only at intersections and pedestrian crossings, and you need to walk all the way round if there are any within the radius of 100 metre because safety comes first. It means that cars (in future also self-driving cars) can drive faster and in case of accident it would be the fault of the pedestrian straying in the street. These are real people with real names who think like that and intend to demand that from others. It is our task to provide more natural alternatives, however, not through activism but our work. Siiri relates to it also in terms of a female architect’s mission as the above has mainly illustrated the thinking disability of men. Gender quotas among decision-makers would really help to change the present stuffy situation.

How many people actually see the elephant in the room?

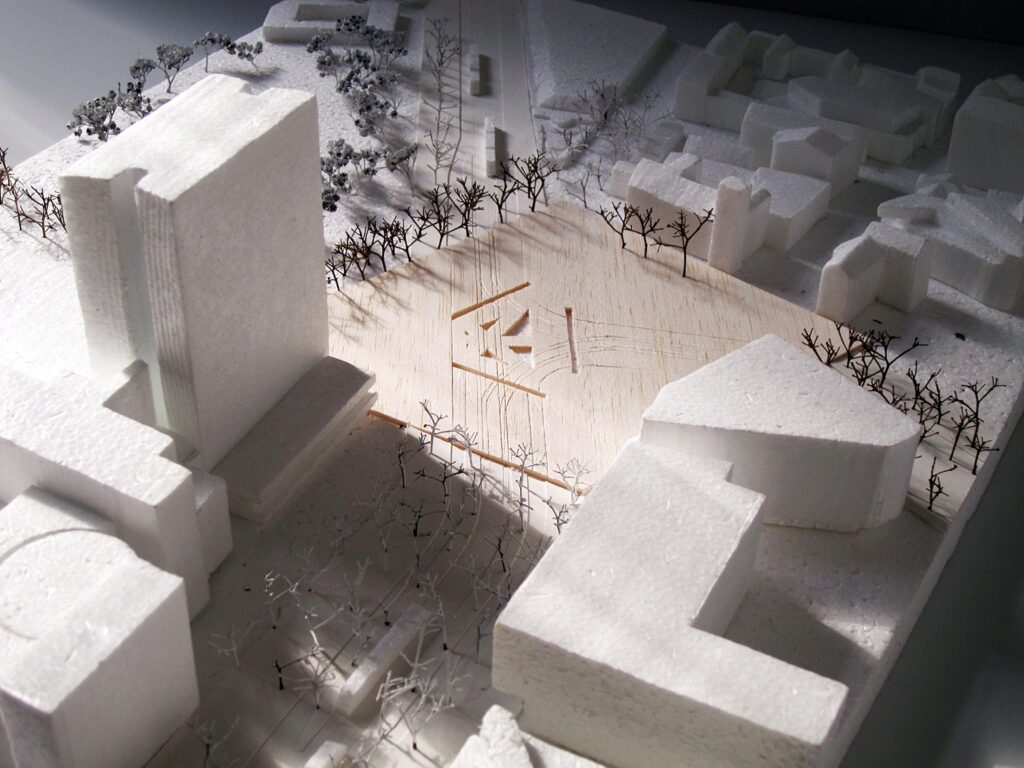

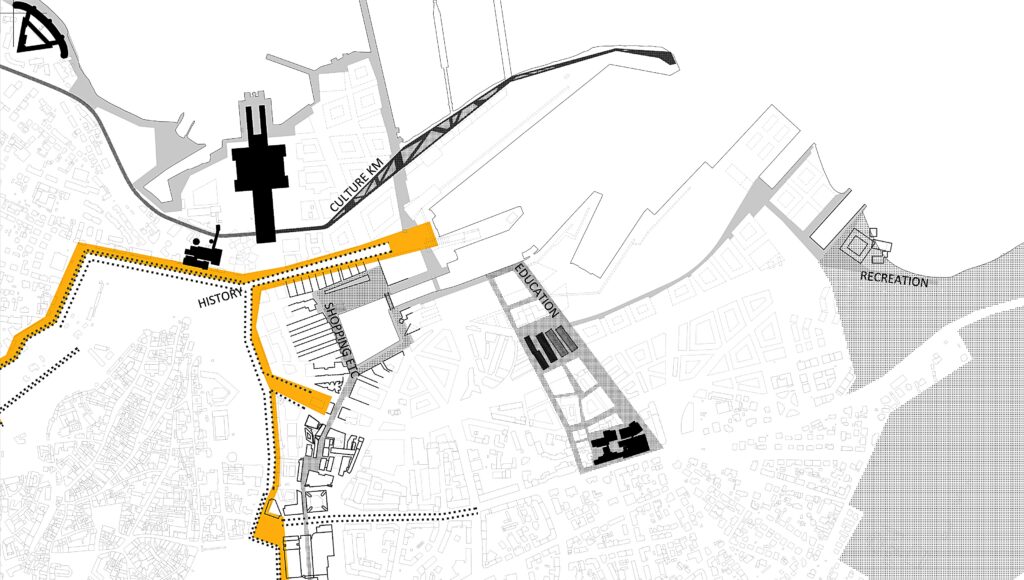

There are some. A good example is the Tallinn city centre seafront vision. It all began from an urban forum. We started from scratch, that is, from the vision of a vision. We asked why Tallinn had not reached the sea so far. Why hadn’t the previous ideas proven sustainable? At the same time, it was really disturbing that in Tallinn the constructions still close street ends and former closed areas at the seaside are planned and built up without a street network as suburbs or as closed as before. Along the former barriers and fences, they now construct new buildings as barriers. If the majority of land is in private ownership and the parts that still belong to the city are privatised without a proper base plan and rules, then what could be the vision? We thought that a vision is an image shared by as many parties as possible. It is not merely the view of one office, an urban design idea or a plan but something much more general. What could be the image that would lead to the initial social covenant? As a result, we got 50 new streets leading to the sea with 80 new city quarters between them. A good dense street network in the city centre that benefits all parties notwithstanding their property. This is how we jointly discovered the characteristic problem in Tallinn (disregarding the lack of vision) – the building stock and street space have not been developed together but separately. Secondly, the city districts should extend to the sea and in doing so, the preference should be given to the development corridors perpendicular to the sea and based on the present city. That was the open source experiment we participated in.

How would you express your personal architectural platform? Have you thought about it?

As a doctoral student I thought that architecture is a discipline of contradictions. Various worlds may be successfully combined with architecture and design, while the contradictions generated in case of logic or verbal thinking refer to an error. I believe that the mutual complementation of several logics, systems or parallel lines is incomparably better and richer than a ‘monolingual’ world.

Also in biology, all systems are duplicated starting from man’s two eyes (to create a three-dimensional image) or senses complementing each other (to provide a sense of reality) and so on. The neuron C is activated in the brain only when getting a simultaneous impulse from two sources (only from A or from B is not enough), while in case of two difference sources, only a momentary impact is enough. And so on. These are so-called stereophonic identities. Even Arvo Pärt’s music, despite aiming at an undivided one or unity, is based on two connected voices.

In case of all the above, the most interesting aspect is not how a credible illusion of the whole or a new world is created but the contrary: an encounter with the so-called unfinished reality, the possibility of new knowledge through architecture. Contradictions are intriguing. In such a world, logic is the incomplete and insufficient model of reality.

Aesthetically, for instance, it means that such multiplicity should not be covered or disguised even if it seems ugly or unfamiliar. The architect’s dream is not to provide interior design for the entire world or pad everything with impressive design. You can select the places, determine the articulation and give a new form only to the selected part. We work within such a world, not on it. We change the articulation of the world but we do not cover it. I would like to leave the user with the option to peek into the layers of world architecture.

For example, the installation “The Pier” had obvious cracks in it, the Creative Hub’s layers are apparent but also the ones in the Museum of Occupations although it was entirely designed by us, similarly Narva College or the upside down fountain at Kopli cemetery park etc. We deserve such possibilities as users, for instance, we need so-called reserves in the city, special places to allow us to step outside the world order (the outer space) for a moment like the homeless. Actually, it is an even more urgent need, people must have the possibility to look away at any time without the space constricting them.

The realisation of an idea is always an experiment. For instance, we try to find new possibilities to take the process from the idea to the execution. Mere philosophy is not interesting to me. I am highly interested in how the idea can be realised in real things and what happens to them later.

Also in case of cooperation, it is good if Siiri and I complement each other. Almost all my closest relatives are graduates of the Academy of Arts or with similar background while Siiri’s family includes only mathematicians and engineers. For some generations already.

How does the new generation use space or architecture?

We count on them. We actually clashed with the use of space of the generations X and Y of late 20th century. An elderly mathematician wrote that the problem of the IT era is not that machines start to think like people, instead, the problem is that people start to think like machines. We see it every week when students show us rough data and non-cleaned-up digital maps along with the ideas. We also use various gadgets and new possibilities to make our work more effective, however, it often means that instead of 3D image you also need to make a video, in other words, we need to work an hour longer. This way the quality of life actually decreases. And it should not be like that.

People’s immediate living environment must be able to balance it. According to Siiri’s vision, people’s lifespan soared at the end of the 19th and early 20th century due to urban planning, as the insolation requirements brought sunlight indoors and people no longer lived in the basements, similarly channels and water supply network were constructed. Now we witness the next level: due to the new quality of 21st century urban space, people can move outside more. It does not only mean cycling paths or the reorganisation of the urban space but the green networks passing the city etc. It is quite common elsewhere that parks are connected with each other. I saw with my own eyes how the people from the new IT agency went for a swim at Kalaranna. They can afford such luxury during their lunch break: go for a dip, even naked if they wish, in the middle of the day in the city centre without disturbing anyone. At times, Tallinn can still afford it.

The other vision is the urban life on the local level. In the future city, life and work can again be close to one another. We made a presentation at RIBA in London earlier this year with my speech entitled “Local Architect”. Our home is in Kalamaja, our office is in Kalamaja and now also the university where we teach is here.

How much do you borrow methods from other disciplines and use theories outside architecture?

I don’t do it consciously. It is easier with a wider cultural background as there are more links. I like to play musical instruments for fun and it certainly helped when we designed Arvo Pärt Centre. I was intrigued by how he structures a musical composition like architecture.

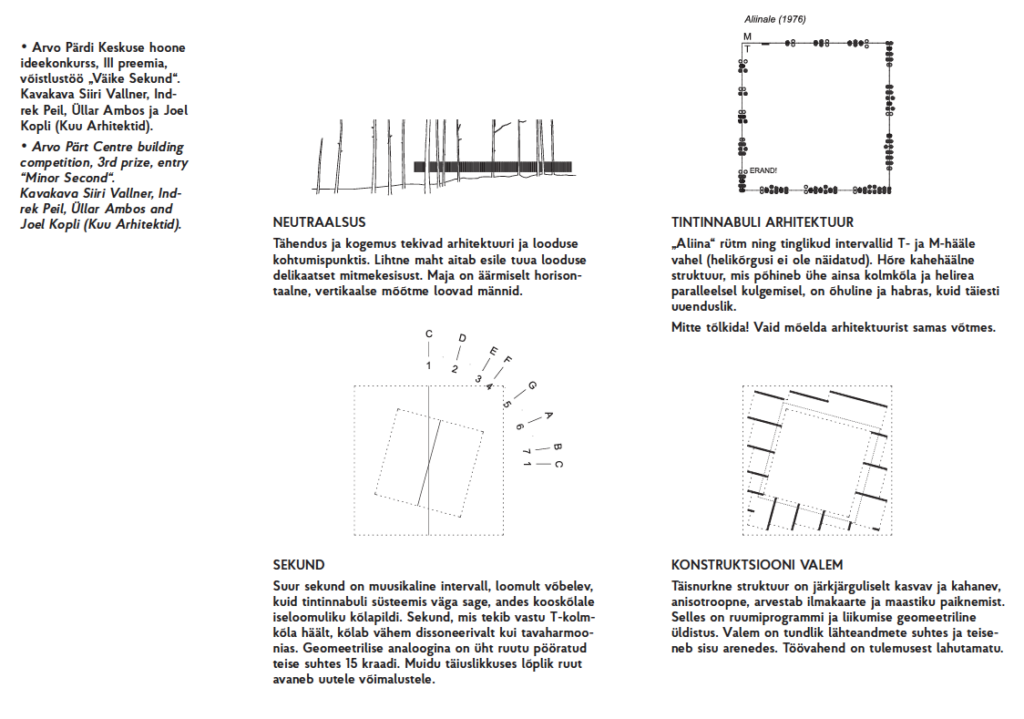

In your competition entry for Arvo Pärt Centre, you used the concept of a minor second. Was it meant as a metaphor or did you design the work as a musical composition?

Not quite. We had some ideas already based on light and the relations between architecture and nature, when the acoustic department SoundLab of Arup’s New York office wanted to cooperate with us. Their idea was an acoustically semi-transparent space with a double acoustic wall and an intermediary space that according to them was based on Pärt’s music. Eventually we still discarded the idea, as it would have required a central hall that did not fit the requirements of the place. At the time, I was interested in the work “Für Alina” – a simple composition from 1976 generating the tintinnabuli style. In its simplicity, it immediately corresponded to the plot in Laulasmaa and to the special spatial sound of Pärt’s music in the New York acoustician’s imagination. Some of the diagrams described also the given additional layer. It was a relatively primitive attempt to compare our ground plan and the architecture of Pärt’s music. The interval of a minor second emerged with the turn of two squares as intermediary spaces appeared and so on. I have later read that Pärt used to live in Mustamäe while writing it and often went for a walk in the pine grove. Such are some of the links between a musical composition and our work.

It is often said that KavaKava’s architecture appreciates the location. It is quite a common description. Do you have a particular approach to it?

It varies greatly by project, it is important to determine the so-called right topics. We have always made a lot of models, mostly with the surroundings. Here we are also interested in generating a new meaning. We try to find the valuable aspects and make them visible. For instance, we retained a part of the old building in the first competition of the Academy of Arts, in case of the Port of Tallinn we mapped the little that was remained of the heritage and so on. Similarly, we teach our students that it is more laudable to turn one poor or boring place into something better than to redesign something that is already valuable or interesting. Many people do not think about it immediately. With the students at the university, we attempt to map, analyse and design the new solution simultaneously. There are always several options and their comparison is an integral part of the process. Sometimes we try to bring out aspects that first remain unnoticed, but lately also the other way round: to give meaning to the most obvious as in case of the bastion belt of Tallinn Old Town, for instance.

The scale and aims of the installation “The Pier” and the urban vision projects are highly different, however, they do have something in common, we may say perhaps that the approach to the solution recurs.

In the project Viimsi School for Young Talents we attempted to conceptualise the connection between the klint and the landscape. The school gradually transmutes into bridges leading to the klint terrace. Thus, interesting spaces and outdoor classrooms are created.

Let’s push it a little. This year you won the Wooden Building of the Year with the fire station in Vastseliina. How can you be site-specific with a standard project?

That would be indeed going a little overboard. Fire stations used to be wooden and that is one of the reasons we wanted to use only wood there. This way it could potentially fit into different small rural areas. The building is square in shape and it may be oriented in two directions, but it could also be related with a specific site. The standard project is consciously designed to be flexible, variable and universal.

One of the key elements of standard projects is the financial saving. To what extent did you consider it as a potential problem when accepting the assignment – their expectation for something as cheap as possible?

The small budget is often given as an excuse by those who can’t do their job. But it cannot be a justification. It is important to be economical to ensure decent standards even for buildings on a small budget. We had designed several social buildings by that time: a shelter, orphanage, city sauna, fire station… The standard project is the best solution for that purpose. Smaller communities do not have the money to create every time new architecture and it is disproportionately expensive. Once we went to South Estonia for fire experiments and that was the time when some of the fire brigades were closing down, it was their last day at work. So, we could take a closer look at their life. Currently, the first building – a prototype – has been completed.

You have allowed the fire station to be altered and extended. What is your experience with the copyright protection?

In this case, the changes form an integral part of the project. The Union of Estonian Architects had agreed on it with RKAS already before the competition. I don’t actually think that it is the right approach. I hope that they will make better agreements in the future. The author primarily bears the responsibility and liabilities and this should also generate the rights that need to be protected.

How do you feel about your concept being implemented by someone else?

In architecture, the idea and its implementation are clearly inseparable. But projects are different. At the beginning we know what our relation to its authorship is. Some conceptual works such as the seafront vision that we designed with Toomas Paaver, Linnalabor and others are open source. We are only glad if the ideas are developed further.

A lot has been recently said about the balance between self-organising and pre-programmed spaces. How much do you think about the fine line in the work process? Do you programme it in your head that this area or building could have the potential for self-organisation?

This includes several topics. The issue of control and freedom has always intrigued us.

One thing is when they in a way discover or fight for the retention of such self-organising places, for instance, Kalarand or Beta-Promenade or thousands of other less-known places. I consider such freedom as an opportunity for and a component of the urban space of the new era. The space that is maintained by the user with meagre means provides it with the important feel of immediate feedback and the possibility to design the space on his own.

Here I would also talk about the importance of planning. Diversity could similarly be a priority in urban planning. Likewise, freedom should be planned in the city much like the density of connections and the variability of space. The appropriate new planning strategies need to be found. For instance, the biodiversity in wooded meadows increases due to human activity. If we transfer the given idea into urban planning, we could think about the richness of typological combination and cross-usage generated as a result of particular semi-organised spatial situations. I have come to call it an urban wooded meadow. We have never talked about complete self-organisation in case of architecture. There are different types of order or ways to organise space. Looser order may actually mean (and mostly does mean) more preliminary work or tests for the novel approach. Also here music may be used as an analogy.

The initial idea of the Creative Hub was actually an open cauldron. We determined the main issues: entrances, some support structures, areas creating the main spatial impressions such as the boiler room, and also the movement between the rooms. We divided the building into blocks and sorted out the entire system, transferring the old industrial logic into the present day. At first, we thought it would be enough to design 10% of the object leaving 90% as it was. Eventually it turned out that the given 90% that seemingly did not get any intervention and looks as if it was left untouched required most of the attention. The space without a programme was to be universal and specific at the same time, a combination of spaces of various size and functions. The building itself dictated it.

Could it happen that the self-organising space is not activated as quickly as a programmed space? The launch curve remains flat calling for hasty criticism.

That is precisely what makes architecture and landscape architecture so interesting – you cannot be sure of your success. We see it also in the Creative Hub where planned and designed areas work better while some of the areas that we left free are now closed, shut or just arbitrary. We should also take tips from old buildings on how to construct buildings with a permanent value as they have been reconstructed several times over the years without losing their value.

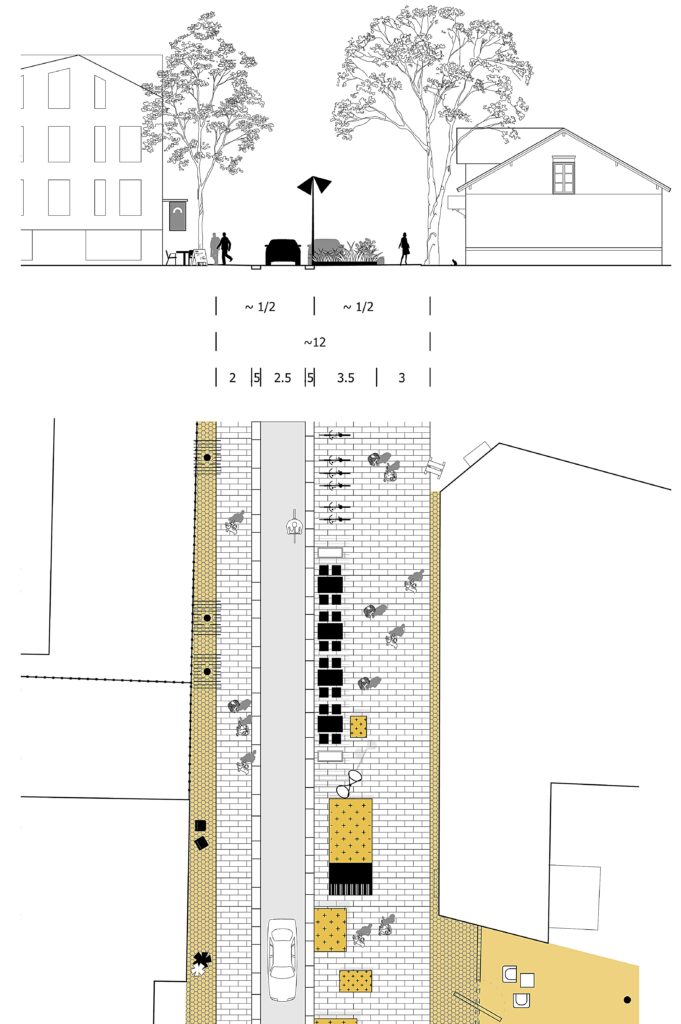

In case of Vana-Kalamaja Street, we reached the idea of self-organisation because we feel that Kalamaja is at times already too well organised. On the other hand, the strongly involved community has become a part of the local feel. Our solution is partly based on the curated elements while leaving other parts free, however, it is difficult to say at this point how much there is free energy looking for an outlet. If the street design brings together the best parts of the city and rural life, then it is bound to create a particular atmosphere. The exciting part is that we do not know yet to what extent it will work.

Are you always an architect or does the citizen in you take interest in something else?

Of course it does, but this is also a smooth transition between various interests. For example, we spend a lot of time outdoors and thus get an immediate urban experience. Your perception of the city is considerably shaped by your experience. You can ride a bike all year round. It takes ten minutes to walk to work from home. There are several possible routes to take. You can live in the city centre but a 12-minute train journey takes you to acres of forests and fresh air. You can combine the types of movement. The city is in constant change. A clever user quickly discovers how to improve his urban experience and makes constant adjustments. You can discover a new place or opportunity every day. When we moved our office one kilometre closer to the centre, it made our daily urban experience even more positive. When riding a bike or walking, the experience is continuous, not fragmented.

Any kind of practise develops your so-called performative knowledge, that is, your professional ability, the skills to use the knowledge in one or the other area. It is not only a craft but the skill to use and develop the knowledge. It is like playing an instrument that can be learned in various ways. The same applies to thinking and using the knowledge. Or using the city.

When looking at the traffic jams, tailbacks and crowded trams, we are bound to ask if people never learn. Why isn’t free and positive urban experience available for all, why are there accumulations if Tallinn in general is largely devoid of people. What prevents us from seeing and making better choices? Why are children taken to school by car each morning? Does the average distance between work and home have to be more than ten kilometres? Why don’t people choose and adapt, but instead yield to the unpleasant routine and repeat it day after day? On the Latvian Day of Independence we watched their most popular film from 19671 and we could clearly see that sidewalks in Riga were considerably wider than now. The latest statistical yearbook includes a surreal quote on the street network of Tallinn, “The most remarkable change in the second half of the 20th century is the continuous narrowing of sidewalks”.2

This is where urban planning in the 21st century style comes to play. According to the new way of thinking, Tallinn is not shaped like a butterfly. The narrow strip between the sea and Lake Ülemiste is actually empty, the wastelands alternate with sparse housing. People cumulate because they use old well-trodden paths and types of movement. At present, the renaissance of streets may be perceived in the world: the urban space is reorganised. The inner nature of man has not supposedly changed over time. Individualism may be a dead-end as it makes us unhappy. People want to communicate and walk with their kind just like in prehistoric times and a good city should allow that.

MIRKO TRAKS is a landscape architect and CEO of Kino – a man from the frontline.

HEADER photo by Renee Valner, graphics Margus Tammik

PUBLISHED: Maja 95 (winter 2019), with main topic Drift

1 “Four White Shirts” (Elpojiet dziļi, Latvia 1967, director Rolands Kalniņš)

2 The statistical yearbook of Tallinn “Tallinn arvudes 2018”, p 102