The trio of landscape architects in Tartu represent the new obstinate generation who believe in nature’s power of self-organisation and assure that their cooperation will persist until Estonia is entirely covered with a high-quality public thicket.

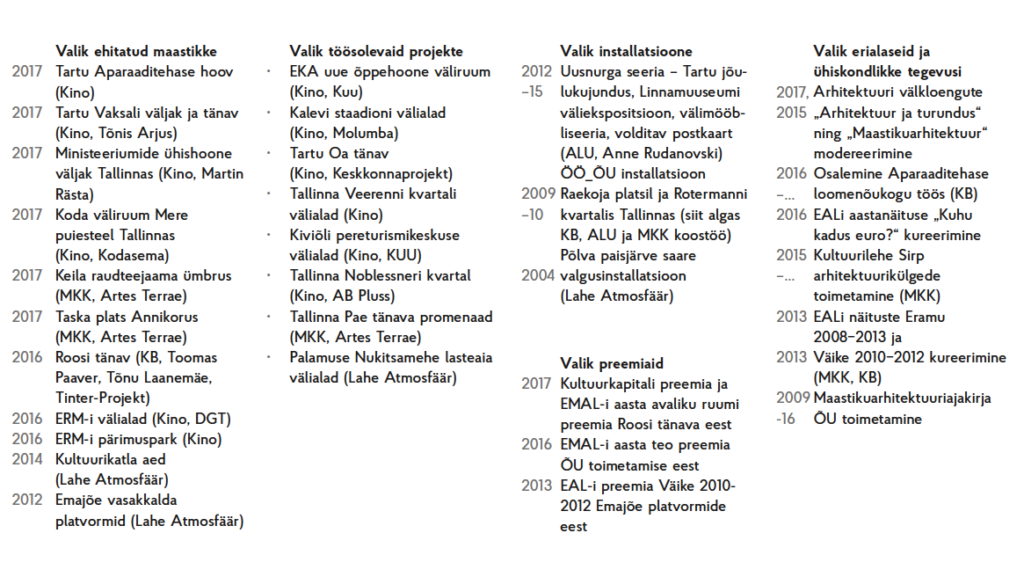

KARIN BACHMANN (1976), MERLE KARRO-KALBERG (1981) and ANNA-LIISA UNT (1982) graduated from the Estonian Agricultural University (present Estonian University of Life Sciences) specialising in landscape architecture. Karin has additionally defended her Master’s thesis in Urban Studies and Merle in Urban Landscapes at the Estonian Academy of Arts. At present, Merle is studying journalism at Tartu University. Anna-Liisa has participated in BA studies in the Swedish Agricultural University and doctoral studies at the Edinburgh College of Arts with the thesis in the making. All three of them have taught at the Estonian University of Life Sciences for shorter or longer periods of time as well as in other higher education institutions providing spatial design courses.

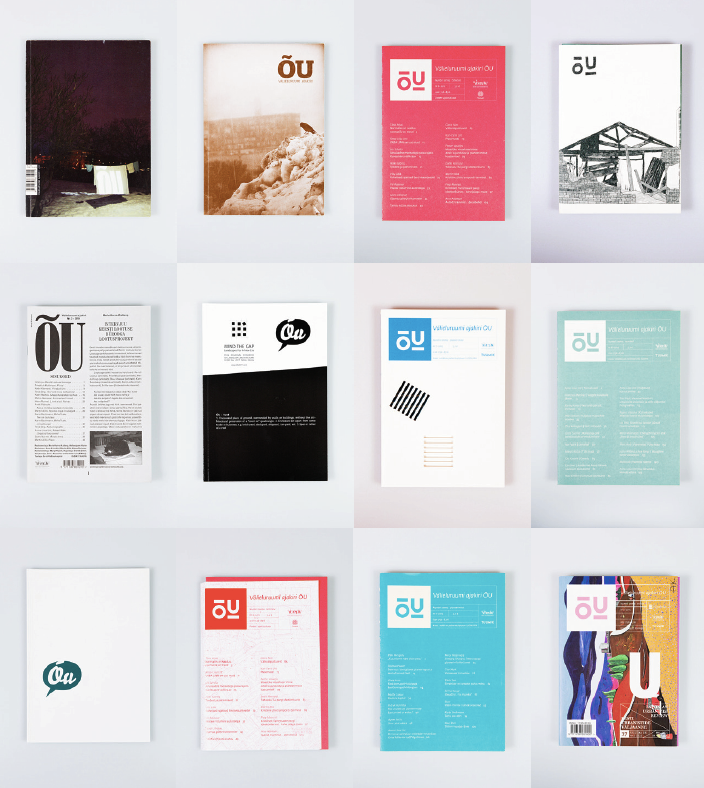

In 2009, the three of them established the pioneering landscape architecture journal ÕU, they regularly contribute to other publications, organise talks and curate exhibitions. For several years already, Merle has been the architecture editor of the cultural weekly newspaper Sirp fostering correspondingly the discussion on landscape architecture and urban space, and she also participates in the projects of the landscape architecture office Artes Terrae. In her full-time job at the architecture department of Tartu city government, Anna-Liisa is responsible for urban design, while her small office Lahe Atmosfäär mainly deals with projects on a smaller scale. Karin’s main job is at the office Kino (established in cooperation with Mirko Traks) and she also participates in the daily work of the artistic council of culture factory Aparaaditehas.

Interviewed by Katrin Koov

In connection with an exhibition at the architecture biennale, Tallinn was visited by the Danish architect and urban ideologist Jan Gehl. There are several similarities in your work with Gehl’s principles – you talk about the importance of public space and the human scale in the space between buildings thus encouraging people to appreciate the role of landscape in it. The work of an ideologist requires a lot of patience and enthusiasm. You have been active for ten years and the ideas are gradually coming to life. How did you imagine your work as landscape architects 10-15 years ago?

M: When I graduated, there was no such work that I wanted to do. It was the time before the building boom years and landscape architects were mostly employed in planning, there were virtually no outdoor space design projects. For ten years now, we have actually been creating a market for ourselves in order to do the work we consider necessary.

K: Upon graduation, I only had a very vague idea of what I wanted to do. I went to work as an urban planner at Tartu city government compiling terms of reference for detail plans, and while working there with Indrek Ranniku, I gradually came to understand that I was primarily interested in public space. I went on to do my MA in Urban Studies at the Estonian Academy of Arts and it was there that I sensed a shift in paradigm – I understood that I had to start learning.

A: I imagined that I would work as an artist-technician or in applied arts, I was in eager anticipation.

How has the reality compared to the dreams?

K: It is more versatile and complex. At school it seemed that the work of a landscape architect is only related to designing, while in reality the work could be done in many different ways.

A: In addition to creativity, the daily work also comprises a considerable amount of arguing, explaining and adapting – I had not foreseen that part, but it wasn’t a disappointment.

M: If I had been less naïve upon graduation and known how many times seemingly logical ideas must be reconsidered, it perhaps would have been discouraging. But we shouldn’t underestimate the youthful enthusiasm and naivety. Now with a hindsight, it’s nice to state that you shouldn’t get tired. You must remain persistent, independent and strong-willed.

K: Being in a group of three or in our other teams provides support. When working alone, you would quickly get stuck, you always need some reflection. The greatest achievement is perhaps when your own words go around a full circle and somebody tries to convince you with your own words.

A: The difficulty is precisely what makes you act. The reward at the end is all the sweeter.

Today it is almost impossible to cope without cross-disciplinary cooperation. Tasks are complicated and knowledge divided. Being open and curious, you have come to participate in interesting cooperation projects. This has also led to mutual trust with architects and other cooperation partners. You have accomplished this very naturally.

K: For some reason, there is occasionally still some need for the formal promotion of the specialty (for instance, by means of leaflets) and the profession of a landscape architect is considered valuable in its own right. I believe that doing your work as well as you can is the best way to advertise your profession. We in Kino, for instance, have never felt any mysterious opposition between architects and landscape architects or suffered from non-recognition. If you always strive for high quality, do not lower your standards (also in details) and consider others, both you and your profession will be valued accordingly.

M: Many graduates imagine that upon graduation they will be greeted by their dream job allowing them to design spaces as seen in magazines or online. This is not usually the case, you must begin by proving yourself, convincing road engineers, local government officials, maintenance companies, and also architects…

K: Author supervision is here a good example – if in Roosi Street I did it myself and pro bono, then for Vaksali Square it was commissioned already on the city government initiative. Such trends are further enhanced in case the landscape architect is taken as a competent member of the team, not as some hippie with no experience in construction or real life who is not willing to make any compromises. Inflexibility as an image can be dangerous.

There has been a gap of 50 years in the landscape architecture education in Estonia. Estonian Agricultural University opened it as a new curriculum in the 1990s. Then again, approximately at the same time architects came to acknowledge what an interesting new field landscape was and rediscovered contextual architecture. This brought about the need to learn more about landscapes. So the competition, but also convergence of the professions, started. In the course of the experimental workshops at the Estonian Academy of Arts, we also came to meet you for the first time, with fire in the eyes of either side.

With competition in architecture tough as it is, you needed to set also your own profession going. How did you perceive your positionin this “big game” at school and what about now?

K: At first I was in two minds, it was both easy and difficult: you find yourself in an interesting place, know nothing and learn all the time. At one point, I came to understand that we can actually do what we want, as landscape architecture had not really been set any frameworks, thus, we cannot really get anything wrong and we can build it all in Estonia. Whatever we do, it cannot be entirely wrong. So, we dared to experiment.

M: At and after school I knew exactly what I did not want to do. In some sense, opposition is always easier. Then again, disagreement can be fruitful only at the beginning, at one point a coalition must be established in order to implement the ideas.

K: The extreme ends were marked very well at the time. To put it simply, at one end of the spectrum there were manor parks and at the other end there was modern architecture and urban landscapes towards which we were drifting.

M: We still haven’t been taken too seriously within our profession. They still sometimes look disapprovingly at how we handle things.

Which stages or landmarks would you like to highlight in your professional development?

K: In my case, going to the Estonian Academy of Arts marked a turning point that messed up my mind in a good way. The second big change came with the establishment of Kino. Working for K&H before that had provided a solid basis and taught me to perceive the reality. Meanwhile we also established ÕU and our trio took shape. The third major stage is now. The office of Kino is situated in Aparaaditehas where I can also work on the development of the culture factory. Steering the daily operations of such a large organism is positively stressful.

M: Graduating from the Agricultural University, going to the Academy of Arts, establishing and editing the magazine ÕU, the annual exhibition of the Union of Estonian Architects. My work as the architecture editor in Sirp has expanded my horizons immensely.

A: The school years and the attempts to achieve more than expected. Participating in competitions as a student. Studies in Sweden which inspired me to make some changes also in my own school. And I could do that a little later as a lecturer at the University of Life Sciences. At school I considered the works of young Estonian architects as stunning role models and my internship at Kavakava had a considerable impact on my path. At present, I work for Tartu city government where the daily administration and bureaucracy help to make better sense of the process.

What is the agenda that you always pursue in your work?

M: Thickets! It’s commonly believed that it is a sign of deterioration. Actually we should consider this as a landscape resource. Honestly, it was our conviction already long before the publication of Valdur Mikita’s books. From the point of view of landscape architecture, a thicket is a possibility: the self-organisation and continuous growth will eventually give you an opportunity to achieve impressive results with ecologically little effort. It doesn’t take too much to make the environment pleasant, balanced and decent. Then again, self-organisation is difficult to curate.

K: We have always attempted to reduce the elitist features of public space and make it user-friendly. A good space is a well-functioning space and that should be easy to comprehend.

A: Sensitivity and integrity in landscape architecture is reached at a stage when you don’t propose well-known solutions. If you do what you have always done, the result is merely an empty formality.

Self-organisation is a highly ecological approach considering for instance the effects of climate change. Also more and more new buildings are designed as “self-organising organisms”.

M: Precisely, that’s very reasonable. But when talking about landscape architecture, it has seemed reasonable only for us for a long time. For example, the natural meadow around the Estonian National Museum is not supposed to be mowed, but people complain that the surroundings look squalid and ugly.

K: The museum eventually put up a sign explaining why the landscape must look like that. It seems we still need to write a few articles to explain it.

M: The conservatism of Estonians is well evident in outdoor spaces: lawns must be mown, leaves under the trees must be raked, garden plots in straight lines, flowers in flowerbeds, weeds are ugly etc. In our exhibitions and talks we have tried to explain and encourage people to trust self-organisation more.

K: Steps must be taken by either side. There should be someone among officials who is brave enough to allow the implementation of such ideas. Fortunately, there were several in the previous Tartu city government.

Learning from nature and transferring laws of nature to the city seems to be one of the key issues of contemporary landscape architecture. There are usually no clear borders in nature, transitions are diffuse and spaces in constant change. This is the natural form of existence. How could the principle be better reflected in the urban space?

A: This topic has always followed us wherever we go. Naturalness is also the topic of my doctoral thesis – landscape is a good agent demonstrating how the constant reconsideration of tactics leads to the most reasonable solution. The aim of nature in an urban environment is to enrich and balance the living space, but we should not forget man as a part of the system. The borderline where the two meet, the so-called edge effect, is the topic that has thrilled me and all three of us consider it as the foundation of our goals. It is not only nature that is important in the urban environment, it’s the synergy with people.

M: Interacting with nature and learning from it was discussed already in antiquity. During the rapid urbanisation period in the 19th century, it was dug up again. Ever since that time, there have been attempts to make cities “more natural”. Actually, there has been no great innovation in that area, nature is merely copied. If in architecture, innovation is based on technology, then in landscape architecture, the interaction with nature has so far been perhaps the most innovative one. Nature may, of course, be imitated also in a lab, as could also be seen at Tallinn Architecture Biennale in autumn, but in my opinion, we still have a lot of genuine natural potential left in Estonia and the research innovation in landscape architecture could rather take place on the level of more traditional biology and ecology.

K: In designing self-organisation, it is important to acknowledge from the very beginning that there is no such thing as an entirely self-regulatory and maintenance-free area. At first, for instance, a so-called favourable seed mix is combined and the appearance of the ecological community is steered with selective weeding and precisely calculated scything. The key principle lies in accepting that the natural community is in constant change – people will one day hopefully get used to the fact that there is nature in the city. In order to make it more acceptable, it’s necessary to plant poppies and cornflowers first. The landscape architect’s knowledge on botany must be considerably improved in order to understand the functional logic of nature better and become equal partners to botanists in the undertaken projects.

When I was writing the maintenance instructions for the National Museum, I realised that the most drastic changes were to be undertaken in landscape maintenance. This work could no longer be done by cheap labour who only come to mow the plot once a week, but they must know the plants very well – in order to know what and when can be scythed and weeded. Then again, botanists, biologists and ecologists need us as well. They also wish to bring more nature into the city but for other purposes. Here the knowledge must be combined and the urban nature steered in cooperation, considering the diversity of both aesthetics, urban space and biology.

As another major and related topic is that of animal rights, I try to consider also animals in my projects either directly or indirectly: so that the bushes would not be cut during the nesting season, that there would be peripheral areas to inhabit, that there would be food for insects, that hedgehog paths would not be filled with concrete, that there would be no pesticide contamination etc. People often do not realise what a huge effect some little action or inaction could have on animals.

The magazine ÕU has been an important platform for you to conceptualise landscape architecture. Could you say a few words on how you came up with the idea and what the original aims were?

K: It was 2009 and we felt that we had a lot to say. As we were so awe-inspired, we couldn’t possibly expect to have anything published in Maja and spatial topics were not discussed at the time in Sirp, so we had no medium. The first issue was published under the Estonian Landscape Architects’ Union, but then already as an independent NPO. At the beginning, we felt that we needed to do it quickly before somebody else does it first. Now it seems funny, of course, as there was nobody else.

M: ÕU has always been based on enthusiasm. We have done it at the expense of a good night’s sleep, daily work and families, mostly by the sandbox or behind the kitchen table. Now that more platforms have emerged, the enthusiasm has slightly waned as landscape architecture is discussed also elsewhere. The greatest lesson that I have learned from publishing ÕU is the understanding of how differently things are perceived and handled within the profession. It was our principle from the start that we wanted articles by specialists of various fields in order to reach a wider scope of integration. This was frowned upon.

Landscape architecture is primarily a practical field and ideas are best explained through completed projects. Fortunately, the number of commissions for exterior space projects has increased. Which projects would you like to highlight when considering their social impact?

M: I would underscore the surroundings of Keila railway station in cooperation with Heiki Kalberg. This was completed more or less according to the original project, including the planting, which for some reason is usually the first to be excluded in a landscape architecture project. Another reason is that road engineers included landscape architects in the project although it was originally a traditional street project procurement. Actually, it was the first railway station in Estonia oriented to pedestrians and cyclists. Then again, it also highlighted the bottlenecks, for instance, people cannot use two-way cycling lanes. There is also some confusion about the large number of bicycle parking spaces. But I believe that once you provide the means, they will eventually also be used. Bicycle lanes provide a clear signal that this is the preferred mode of travel.

A: All projects have been important in providing lessons in how the field actually functions. As the proportion of my design projects among other work is relatively small, I still have a lot to learn. The Christmas design on Tartu town hall square received perhaps the fiercest public attention, that was a true acid test. One year, sculptor Anne Rudanovski and I proposed a non-traditional solution for Tartu revealing the extreme ends of the emotional spectrum. Some people loved the plywood installation, others claimed not to have seen anything as weird as this before.

K: I would be nothing without my team. We began with Mirko Traks and Henn Runnel, now Uku Mark Pärtel, Kristjan Talistu and Juhan Teppart are joined by. I, for instance, rarely do technical drawings as others do it so much better, so we have different arrangements. I design with words. I would perhaps consider Roosi Street designed in cooperation with Mirko Traks, Toomas Paaver and Tõnu Laanemäe (joined by Tajuruum in the draft plan stage) as one of my most important works. It is a project that we kind of forced on Tartu city government when the construction of the National Museum was decided. I began inviting myself to city government meetings etc. At first it was truly pro bono until the city government commissioned the draft plan. Also, close to my heart are the exterior space of the Estonian Academy of Arts with KUU Architects and the inner courtyard of Aparaaditehas completed this year.

Tartu seems to have been a good testbed for good public spaces and inclusive projects lately.

M: The size of Tartu is convenient, people know each other and so it is easier to explain things. You are also physically present whenever you need to rush to the construction site and check where a bench should be placed or what plants should not be scythed.

K: Projects in Tartu have indeed been successful. In the previous city government, there was a good combination of deputy mayors and officials dealing with the urban space who perceived the need to shift the focus from cars back to people.

You already mentioned that landscape architecture could be practised in different ways. What does your regular work day look like now?

K: When I used to spend more time sitting behind the desk, I sometimes felt bored, I wanted to stand up and do something else. Now it is the other way round – I wish I sometimes had a day when I could sit and quietly ponder on some idea. But actually my working life is close to perfect, so I’m really grateful, I have been lucky.

A: I have actually never worked as a landscape architect in the traditional sense of the word. My daily work since graduation has been somewhat different and my designs have been created as a sideline on the sofa, but in general I have been working within the professional field. I supervised landscape architecture students for a long time at the University of Life Sciences and at present I do the work of a landscape architect at the city government of Tartu, although the sign on the door says something else.

M: My full-time job at the moment is in Sirp and I need to make an effort to find time for other projects. I really enjoy the pace of work at the weekly – every week something is actually completed. This is not the case in design work, some things may be prolonged for months due to arguments and it may take years from the original idea to the finished object. I find deadlines really motivating.

K: Our joint project, however, has no deadlines or any boundaries – it simply began and will last until Estonia is fully covered with high-quality public thickets. But actually, our synergy has been effective due to the fact that we are slightly different from another, yet share the same core values.

M: It is an interesting fact that we have never had a joint landscape architecture design project, although there have been other ventures. And it is likewise curious that all our project partners have been our husbands-partners. This ensures mutual understanding and stability.

Your activities are marked by diversity, meaning that you keep an eye on the social processes with environmentally sensitive antennae stretched out. What are in your estimation the next important challenges for the Estonian landscape architecture?

K, M, A: Speaking about and promoting self-organisation and the human scale has only just begun, nothing has been completed. There has been no change in the society’s way of thinking, old habits die hard. People speak increasingly more about landscape architecture, but they still take it as a way of decorating the outdoor space reflected in triangular lawns and planter boxes. The strips of lawn around parking lots that nobody had better use for do not constitute landscape architecture that would speak to people or nourish diversity. We must work on promoting landscape architecture as a process so that it would be considered as a mitigator of more extensive phenomena such as climate changes, the homogeneity of cities and the proliferation of unfitting places.

KATRIN KOOV has been for ten years one of the partners in Kavakava architecture office. She is the coordinator of the landscape programme at Estonian Academy of Arts. She was from 2014-2017 editor in chief of Maja magazine and since spring 2016 is president of the Association of Estonian Architects.

HEADER photo by Mark Raidpere.

PUBLISHED in Maja’s 2018 winter edition (No 92).