VICTIMS OF COMMUNISM MEMORIAL

Location: Maarjamäe, Tallinn

Authors: Kalle Vellevoog, Jaan Tiidemann, Tiiu Truus

Sculptor: Kirke Kangro

Landscape design: Lidia Zarudnaja

Team: Kersti Nigols, Martin Prommik, Liis Voksepp, Annika Liivo, Marianna Zvereva

Graphic design: Martin Pedanik

Technical design of the Officer’s Monument: Margus Triibmann

Lighting consultant: Siim Porila

Structural design: Estkonsult

Commissioned by: Riigi Kinnisvara AS

Constructor: Haart Ehitus

Architectural competition: 2016

Built: 2017–2018

The minimalist grandeur and archetypal imagery of the memorial engage the viewer up to a point of awe.

Although the memorial is dedicated to the Estonians who perished during the communist rule between 1940–1991, it is also a solemn place of reverence for those who endured the Soviet rule despite the denigration of human spirit.

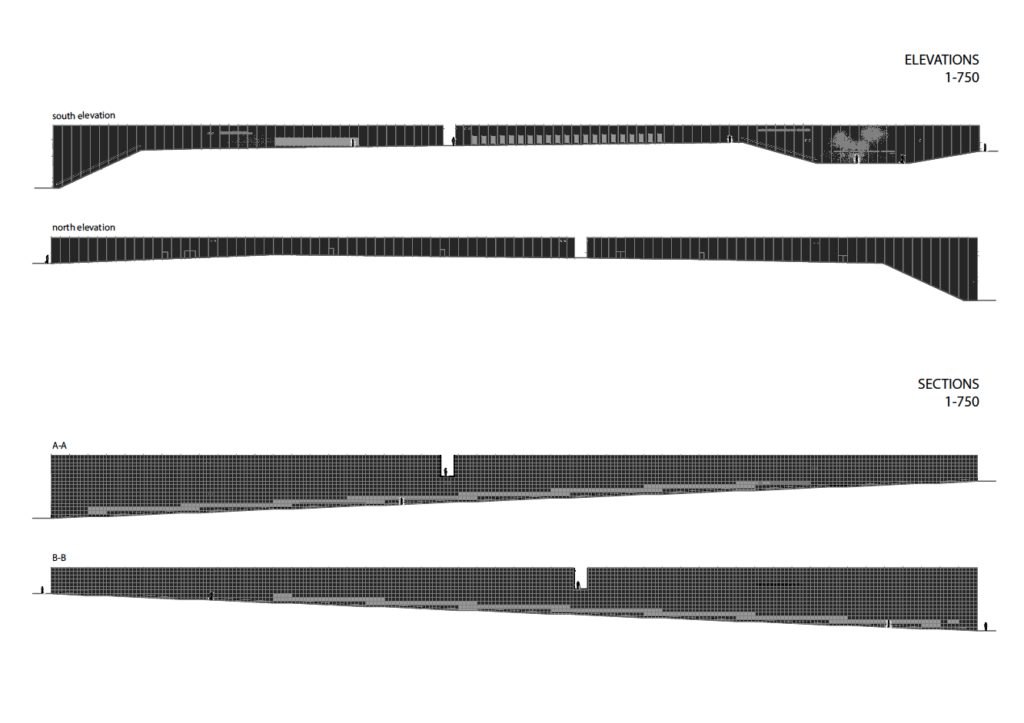

The general form of the memorial – two high black walls covered with metal plates enclosing a narrow crevice – is by nature an archetypal shape that, in slightly different variations, permeates the entire architectural history of mankind. I think a similar form may originate from time immemorial when we lived in caves, surrounded by daunting abyssal rocks that swallowed the lives of many. The effect of this experience, which is ingrained in our collective subconscious, has materialised distinctively in the memorial at Maarjamäe, without copying from known solutions sworn to different religions. The architects have achieved a minimalist grandness not too common in Estonian monumental design.

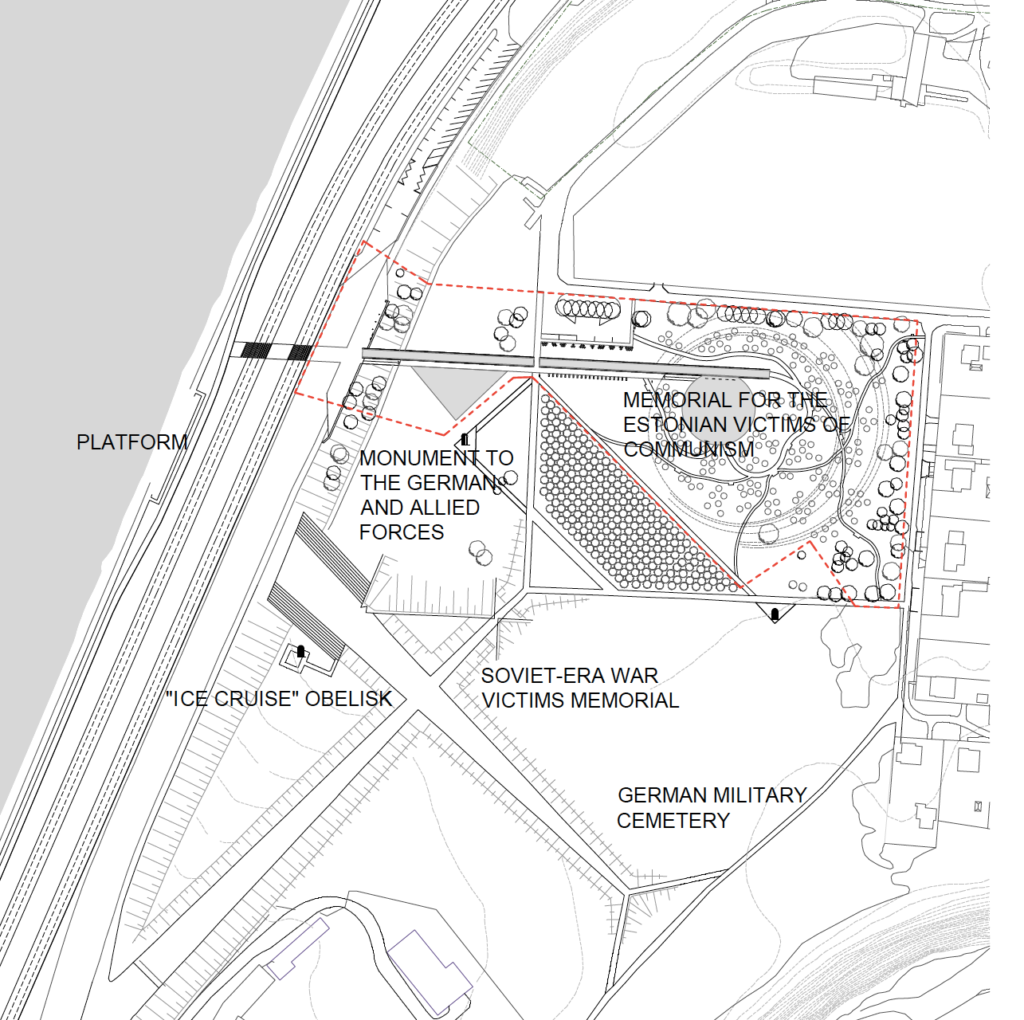

Despite its grand volume, the memorial melts into the Maarjamäe slope naturally, sustaining its aesthetic and mental independence from the numerous monuments built here during and after the Soviet era, one of which makes no claim to conceal the ideology of the “victory of communism“. Nowadays, the popularised ecclesiastical cross is no longer convincing, however large it may be (like the monument at Liberty Square in Tallinn). The modern day calls for a more general archetypal image, one that also sources from the new technological world and outpaces the historical timelines of the main religions. These images dwell in the deepest corners of man’s soul. The memorial at Maarjamäe has succeeded in reaching them.

The main spatial element of the memorial, the “tunnel“ between two large planes, creates here a special metaphysical world that should disentangle the visitor from the mundane. The names of tens of thousands of victims engraved on the black metal surface concretise, even personalise, the national tragedy, perhaps even reminding the powers that be, who still justify the communist crimes, of the atrocities of their predecessors. It is fair to say that the created space shocks the viewer, but instead of proclaiming horror, it opens toward the sky, the sun, the rain, the snow, and the stars. The victims’ descendants, and anyone else who empathises, are able to grieve and honour them by bringing flowers or burning candles as a sign of a shared spiritual bond. A sacred place such as this requires peace and quiet (thankfully, there is no background music, or worse – bells). It was quite shocking to hear news from the media about a planned football stadium next to the memorial, on city grounds, no less! In the total silence of the memorial, we may only hope that such violence be deterred from the future of the people.

An impressive view of Maarjamäe opens from the memorial, as well as of the sea from the end of the tunnel. The spatial situation prompts an idea: instead of leading directly to a road with busy traffic, the tunnel could usher the visitor underground and take them all the way to the sea. The possibility to splash water on the face in the summer, or walk to the ice and feel the limitless grasp of the sea and the horizon in the winter. This would add an extra dimension to the memorial – a consoling message of the infinite freedom of the soul that is available, no matter how cruel the walk on the earthly plane may have been.

In conjunction with the latter, the seaside platform belonging to the Soviet memorial should be demolished. It is a non-form with incapable architectonics and poor construction quality that even the communists did not know how to use in their rituals. There is no effective use for this meaningless object that people degradingly call the Finnish foothold.

Exiting the memorial axis, we enter the green area of the memorial on Maarjamäe, which is dominated by an amphitheatre with an apple orchard planted on its lush slopes. I applaud this idea because it touches the Estonian spirit. An apple garden was part of every Estonian household, although we borrowed this tradition from the Germans. The apple garden epitomises the entire annual cycle of our climate zone. It is like an inseparable family member. We had two apple gardens in my childhood home in Räpina – an old one and a new one; the latter we planted together with my father. The apple is one of our national symbols – we offer it to our friends, and apple cider, wine or vodka to even better friends, and why not to a stranger. But an enemy will always remain outside the apple sphere.

A 12,000-headed metal bee swarm1, with each statuette becoming more and more perceptible as you get closer, is a surprising, delightfully naive addition to the apple orchard. For me, they symbolise the victims’ souls that have returned home. I believe this recognition to be more than symbolic. A friend of mine has told how his father, who was held prisoner in a Siberian concentration camp, would appear in their kitchen in Pelgulinn from time to time. The frightened yet happy daughter would peek through the keyhole and see the dark kitchen suddenly illuminated, his father sitting behind the table.

The main axis of the memorial walls described above is perpendicular to a path that crosses over the tunnel space as a lintel, creating a bond with the adjacent monument, dedicated to the soldiers who perished in the Soviet war. I do not consider emphasising this architectural link important, because from inside the main space of the memorial I thought it was a technical element. The relationship between the two monuments became clear only when I saw the layout of the object. A patch of forest hides the view between these two opposing memorials. Nevertheless, I understand the intent of the authors to make an architectonic statement, respecting the fact that there were casualties on both sides of the political frontier: ordinary people who were forced to deploy as soldiers, others who were deported and imprisoned, are all equal in the face of eternity, and we cannot shut our eyes to the decades that we were forced to spend under occupation.

The memorial is connected with the geometrical dolomite square of the amphitheatre, plaques for the Estonian officers (who have not been commemorated in such an esteemed way until now) on the external facet of the south wall, volumetric objects reminiscent of the deportation and perishing sites of fellow countrymen. Some additional shapes that look like bullet holes in the wall catch the eye. In the midst of all these elements, I wonder if it had been possible to sustain the minimalist approach and avoid narration. I had a similar experience when constructing the Freedom Clock – the city clerk wanted to load the object with an unthinkable amount of messages, as if to compensate for lack of them thus far. Despite the risk, the authors of the memorial have successfully avoided chaos and managed to keep the cavalcade of the information “written in stone“ within the confines of the architectonic structure. This key moment is often where the architect as creator can remain mentally independent of the aggrandising commissioner.

I would like to commend the author of the lighting of the memorial – the design is truly outstanding in our conditions. Perhaps this avenue will take us toward the level of developed European countries where architecture is skilfully illuminated, not overthrown with effects on the facade, but emphasising the architectonics of the object. In Estonia where it is dark for half a year, this expertise is more important than in Italy, for example.

An important part of a memorial is the way the movement of the masses is organised. Here, stairways lead the visitors in a direction that is opposite to logical flow, back to the beginning, exiting the architectonic act and descending toward the breadth of Tallinn Bay, and the inherent sense of freedom. Freedom that has been given to us, unlike the victims of communism, in ample form, which we as a democratic state must keep! Without freedom, there is no economy, no culture, no architecture – even worse, there is no mankind, or life on Earth as we know it.

In conclusion, the memorial is a direct physical and emotional manifestation of what good architecture can accomplish. I hope it will raise the standards for future memorial plans from 19th-century-mentality to the 21st century.

LEONHARD LAPIN is an architect and artist, professor emeritus at the Estonian Academy of Arts.

HEADER photo by Arne Maasik

PUBLISHED: Maja 97 (summer 2019), with main topic Architecture is an Art of Space

1 The number of bees was meant to symbolize the number of victims’ names on the walls.