European Union assistance has had a very strong influence on the appearance of Estonian towns, villages and landscapes in the last decade. Much has been done, but the real question is what has been done, and how. At the start of the previous European assistance period, local governments were encouraged to be active in asking for support. Something akin to a mentality became widespread: if money is being handed out, it has to be accepted and spent.

The weak areas of EU-funded construction – unreasonable deadlines, limited budgets, lack of builders with specific skills, negligence on the part of construction companies and price-based public procurements – were actually nothing new in the construction sector. The limited length of the period in which European support could be used amplified quite a few problems, pointing up more general bottlenecks.

Mere window dressing

It’s impossible to say with finality the volume of work done for European support in Estonia – how many cubic metres of concrete was mixed, poured, demolished, then re-poured; how much asphalt was spread and then torn up again for laying new underground lines; how many kilometres of paving stones for pedestrian paths. No one has kept a precise account. According to Government of the Republic data, the following was built or renovated with EU assistance in the 2007-2013 period

- 60 nursery schools,

- 75 schools,

- 44 cultural sites in rural areas,

- 27 sites in the social sphere in rural areas,

- 60 km of highway,

- 7 university buildings

- 100,000 people got clean drinking water after modernization of water works and sewerage systems.

The largest amounts of funding went to environmental conservation (718 million euros), transport (636 million euros), enterprise and tourism (493 million euros), research and development (413 million euros) and regional development (389 million euros). (1)

Diagramm: Martin Rästa / Anna-Liisa Unt.

Undoubtedly many of the projects were essential and in a few decades, we will probably view the buildings as having the same significance as Baltic German manor architecture or Soviet-era works. Perhaps the era will come to be called the “age of Euroarchitecture.”

The statistics mentioned above should certainly elicit a nod of recognition: the funding was distributed in a socially equitable manner, with support given to building and renovating establishments in the childcare and education sector, and the development of rural areas. The guiding principle was that broader development of the living environment creates more favourable opportunities for development of society and enterprise. The existence of a school in the vicinity gives young enterprising families more motivation to move to the neighbourhood and bring life to the area. The drinking water and sewerage systems suitable for the 21st century will undoubtedly raise the standard of living. If we look more closely at the Euroarchitecture, dive beneath the surface and study the underwater portion of the iceberg, as it were, we see quite often that promoting the quality of the built living environment has seldom been a priority on the same level as solving problem areas for business, the natural environment or agriculture.

The fact that architectural quality has been relegated to the background reflects society’s attitude toward this field in general. Architecture, including landscape and interior architecture, and product and graphic design, are seen as mere décor that can start to be used only after the basic needs are fulfilled.

Lone highway

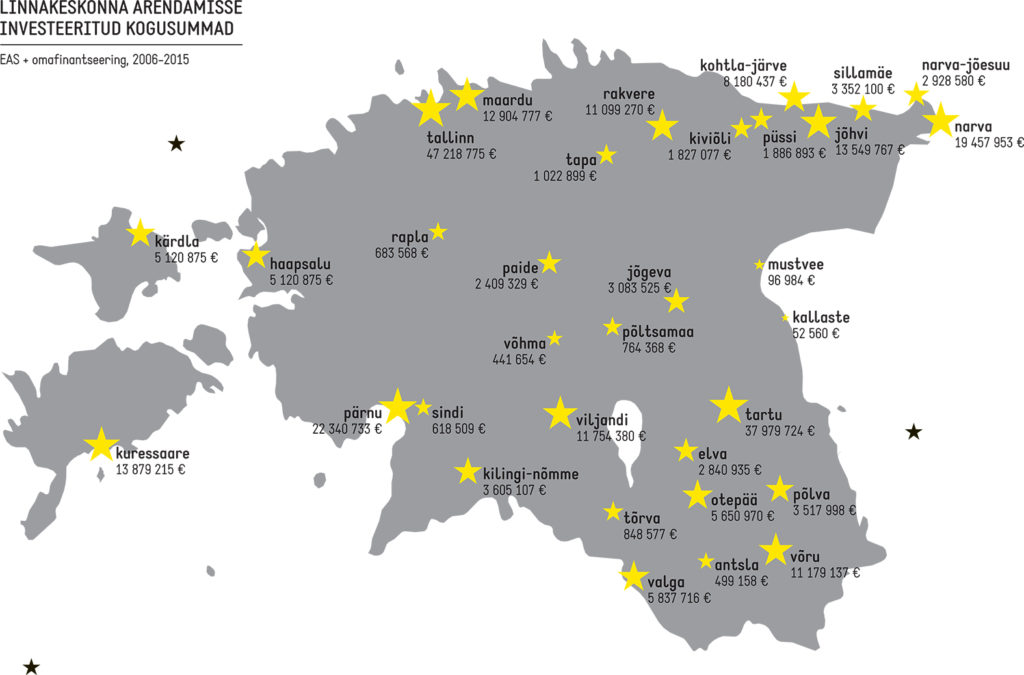

Perhaps the greatest support for the development of urban areas has been channelled through Enterprise Estonia. The Environmental Investment Centre, the Credit and Export Guarantee Fund Kredex and the Agricultural Registers and Information Board have also intermediated funding for building new environments. Funding for large infrastructure projects such as the eastern Tartu ring road, Ihaste Bridge and the section of four-lane motorway at Mäo came directly from EU structural funds.

Photo: Kalle Paas

The distribution of support to respective regions has proceeded along predictable lines. For example, Enterprise Estonia has supported the Tallinn and Tartu region the most. Viewing the distribution of support per capita provides an interesting picture. Enterprise Estonia has invested 115 euros per Tallinner but 534 euros per resident of Põlva. In terms of regional policy, everything is as it should be on the face of it. But if the support doesn’t show up in the quality of the environment, if old-fashioned architectural principles are followed (with regard to, say, street construction) and if there is no striving for innovation, there is reason to ask what has changed for the better and whether the change is sustainable.

The investments into road infrastructure stand out best in the broad view. However, the new highways, junctions, streets and bicycle paths tend to be very monotonous, in terms of the environment, and they only take into consideration one mode of transport. The new routes are a telling visualization of the standardized thinking in road construction. Even the designers of pedestrian and cycle paths also proceed from the perspective of car users: rails, signs and posts are installed so they would be a safe distance from the carriageway, which all too often means that the features that regulate car traffic become an obstacle for cyclists or pedestrians.

The standard-driven philosophy was certainly not “imported” along with EU assistance; the general principle of using the EU’s common treasury is instead openness and transparency. Considering that the construction is funded by public money, the quality and diversity of the built space are just as important as resolving mobility problems. The formal approach sometimes results a public procurement process that is like a caricature of itself, where three bids are required in a situation where only one company is competent to do the work. The requirements of quality and integrity of the environment should be enforced just as stringently as procedural rules.

When the four-lane Mäo bypass was built on the Tallinn-Tartu highway, the former road essentially remained behind. There is now a huge empty highway in the middle of tiny Mäo settlement (population 61) with no purpose. Funds should have been found not just to build the new highway but to make the old highway narrower to adapt it to the new situation. Seeing the big picture should be a logical part of every project, not just a Europroject. Instead, there are arguments about eligible aid.

Seeing the big picture should certainly include a sober assessment of the economic situation. Current economic forecasts cannot be the only input for decisions about the future. One example is the Koidula border checkpoint. The new, modern station with its capacity to handle high volumes of traffic began to be designed at the start of the millennium when economic growth was strong and trade with Russia was promising. Money for modernizing the border checkpoint came from the EU and in 2011, Europe’s most modern railway station was opened. By that time, relations with Russia had worsened and they have not still recovered today. The giant transport centre stands at the edge of Setomaa as a monument to unfulfilled hopes.

The flexibility of projects and space and achieving a solution that is not completely compressed into a framework is certainly a challenge. It is much simpler not to take it into consideration. But we should not forget that the environment, opportunities, and policy are ever -changing and must be factored in. We don’t build with only the current status quo in mind. One of the best and most interesting examples of flexibility is the Riisipere-Haapsalu-Rohuküla railway line. After transport volumes dwindled, this segment of track was closed to train traffic and even the sleepers were pried up. The railway embankment was privatized and turned into a 60 km-long recreational trail with the blessing and support of Enterprise Estonia. Restoration of rail traffic has been considered on several occasions along this segment. A feasibility study has been conducted and a preliminary project has been prepared. Encouraged by the Rail Baltic project, civic associations are calling for the railway network to be made more efficient and more stops to be served. If the Lääne County health and recreational path ends up going “trail-to-rail,” then the interim function of cycle path will have served a good purpose as a reasonable, wise use of the space.

Photo: Maaris Puust

Museums, centres and theme parks

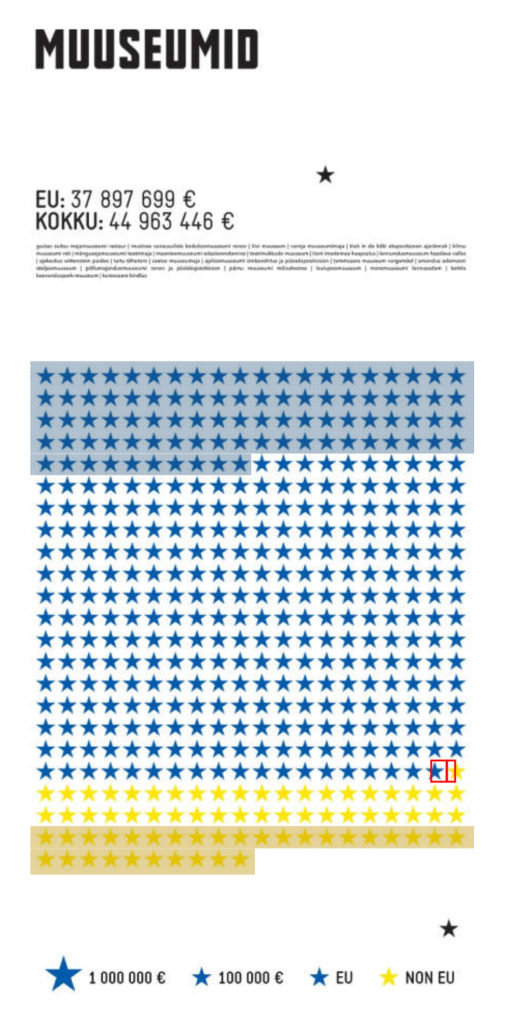

EU funding has wrought the greatest transformation in museums. Instead of a dusty, boring spaces meant only for looking at artefacts, these are now interactive modern amusement parks that play with visitor’s senses and perceptions. Time centres (Wittenstein in Paide’s Order Castle), theme parks (Lotte theme park in Pärnu County), theme centres (Ice Age Centre in Jõgeva County), science centres (Ahhaa in Tartu and Energy Discovery Centre in Tallinn) and visitor centres (Piusa in Põlva County) have all emerged.

Although the general paradigm shift on the museum landscape is to be welcomed, the construction of the various centres raises the question of how much they actually contribute to the advancement of local life. With the construction of Piusa visitor centre in Põlva County, manmade caves from quarrying sand for glass production in the 20th century, previously open to the public, were closed. They can now be seen only on a virtual tour at the visitor centre. The south-eastern edge of Estonia now has a large complex with café and cinema, with not enough money to maintain the café due to the low number of visitors. Regarding the architecture of the visitor centre, Mart Kalm wrote: “Architect Helmi Sakkov wasn’t able to restrain herself in her selection of material for the Piusa caves visitor centre, bloated with European support.”! (2)

Theme parks that are children’s books come to life are phenomena in their own right – Poku Land in Võru County and Lotte Land in Pärnu County may bring smiles to the faces of families with children and be interesting for researchers studying trends in society, but their location and operating model isolates them from the rest of the environment, creating a distorted mirror world.

Putting Enterprise Estonia support under the lens again, we see that record amounts have been distributed for renovating museums. For example, the renovation of the Maritime Museum’s Seaplane Hangars and development of the exhibition received nine million euros in support, and the Puppet Museum got three million euros. Alongside these colossi, the Varnja Museum’s 9,000 euros is just a drop in the ocean. It’s clear that it’s possible to create a much better-conceived environment with nine million than it is with nine thousand. Here the disparity of European funding is exposed at its most striking. Small museums might be able to renovate their exhibitions, but the assistance – which must be applied for in small instalments and with several separate projects – leaves a mark on the construction quality.

Long-term plans

The precondition for high-quality space is placing trust in good experts and collaboration starting from the terms of reference stage. But the inception of the site is only the beginning. The preservation of the built project requires not 5 years but 10 or 20 years of foresight. Each application for European funding must also involve evaluation of the plan for maintaining the building, bicycle path or promenade in the future. For the most part, the requirement for support is that the site remain in operation for five years. Already now, we know of examples of how farmstays turn into private homes after the five year period is up. There should be discussion about whether it is ethical to levy taxes later on public space built for state aid or European funding (Tartu’s Tamme Stadium has to pay for use of the tartan track, for example). A condition for success is good preparations, involvement of the finest experts, making use of favourable opportunities, and a longer-term plan.

MERLE KARRO-KALBERG is a landscape architect, curator of the exhibition “Where did the euro get lost” (co-curators Karin Bachmann and Anna-Liisa Unt), architecture editor in the cultural weekly newspaper Sirp, and is also studying journalism in Tartu University.

HEADER: the investments into road infrastructure stand out best in the broad view. The new routes are visualizing the standarized thinking in road construction. Tartu eastern bypass road. Photo by Tiit Sild.

PUBLISHED: Maja 89-90 (summer 2017) with main topic CHANGING

1 Government cabinet meeting held on the topic of European support at Tallinn University of Technology, Government of the Republic website – 12 September 2016.

2 Mart Kalm, Houses fashioned by computer and farmhouse kitsch. – Eesti Ekspress, Areen, 25 November 2010.