Tarja Nurmi gives an overview of the current state of Finnish architecture and introduces the most outstanding buildings of recent years. Finland, excelled in public buildings, is now facing the challenge of housing.

In the field of architecture, Finland has been considered some kind of a small superpower. There have been world famous architects like Eliel Saarinen, Alvar Aalto and many others, among them also Erik Bryggman. Women like Wivi Lönn and others have also done exceptionally well. It would be difficult to get an overview of current Finnish architecture without stopping briefly on the destiny of architectural heritage.

The legacy of Aalto is now in relatively good hands. In the case of Saarinen, the administrative part of Helsinki railway station has been sold to a hotel company and the station restaurant rented to a hamburger chain. Many state-owned historical buildings that are a part of our national heritage are sold to real-estate investors and optimistically converted into high-end hotels or luxury apartments. When state property is sold to the highest bidders and even speculators, it will be lost for the people forever.

At present, there is a revival of the architects Raili and Reima Pietilä. Both Dipoli building in Otaniemi (from 1966) and the Finnish Embassy in New Delhi have recently been restored and technically updated by ALA Architects. The embassy is a competition winning project (1963) but built and taken into use as late as in 1986. Dipoli with its fantastic concrete ceilings and flowing series of spaces is now the main administrative building of Aalto University (former Helsinki University of Technology). It also serves as a student and staff canteen. After many changes done by some disrespectful or thoughtless owners/users, the restoration-rejuvenation project has been a genuine challenge.

Otaniemi Campus is still known for both its finest Aalto buildings and the lovely and nicely restored small chapel by Kaija and Heikki Sirén. The central building Väre, the competition winner by Verstas Architects built in red brick was taken into use in 2018. In addition to the study areas and workshop spaces, it also includes an elegant underground station, shopping centre and several restaurants. All of the relatively new underground stations between Helsinki and Espoo excel in their architecture.

Nowadays some genuine experimentation is taking place in the field of wood construction. Still, rather many recent examples seem to be a far cry from refined detailing and genuine architectonic quality of earlier years. Quite interesting are some experimental small one-family houses in solid timber by younger architects have made it into architecture publications. There are architecture studios such as OOPEAA, Avanto and others who have recently excelled in building with wood and others follow in their footsteps. Avanto Architects has created the highly popular seaside sauna and restaurant-café Löyly. There is the highly praised Kuokkala Church, originally a winning competition entry by Lassila Hirvilammi Oy and Luonti Arkkitehdit, and the Puukuokka housing project in Jyväskylä by OOPEAA. A rather recent project by the same office is the popular new sauna on the small island Lonna close to Suomenlinna fortress.

Buildings with massive brick walls and natural ventilation also seem to be making a comeback.

In the field of building with concrete, some high-quality experimentation could be mentioned, among others, for instance, a modest distillery building in Ostrobothnia by Avanto architects.

Building and demolishing

Finland is undergoing a building boom but also a strange demolition rage. Even buildings from the nineties are under threat and may or will be replaced by taller buildings with even more than double volume. Similar rage could be noted in the sixties, when neo-renaissance or Jugendstil buildings were recklessly torn down and replaced by soulless or mediocre buildings with lower floor heights. A polemical book by architects Vilhelm Helander and Mikael Sundman with the title “Kenen Helsinki” (“Whose Helsinki”, 1970) was then a highly important wake-up call. It put a kind of a stop to this harmful trend and helped to create the needed resistance. It might be high time for a second round of such critical writing.

In some cities and towns, real estate businesses and construction companies seem to be the ones calling the shots and running the show. Some politicians in Helsinki are even questioning the competence of trained design and planning professionals. There is also a rather one-sided ideology regarding what makes a city and what kind of urban environment is hoped for: perimeter blocks, higher buildings and, again, density, density, density.

The idea of several different typologies coexisting within a city or a town seems to be getting completely lost in the middle of the urbanization hype. There are relatively loud social media groups that demand “beauty” back into architecture and consider all that is new or “modern” to lack in aesthetic quality. The Finnish version of such a social media group has been imported or copied directly from Sweden.

Only Helsinki and Tampere growing, perhaps also Turku?

Not a minor problem is the accelerating urbanization that leaves smaller and previously liveable cities and towns in trouble. The credo boosted also by the media reads as follows: only Helsinki, Tampere, and maybe Turku are important – and that´s it. The truth might be more complicated and the tide might still turn. There is rather a short-sighted trend to accelerate the urbanization development by deliberately concentrating on services of ever bigger units, hospitals, schools and kindergartens included. In the countryside and smaller towns, the property values of houses and apartments are going down in comparison with the soaring prices of housing in Helsinki and even Tampere.

Housing policy, where did it go?

There is also a trend to build very small apartments that is not very sustainable in the long run. These apartments are targeted to investors – private or corporate – but do not even meet the minimum spatial standards of post-war times, when there really was a severe shortage of housing.

The Association of Finnish Architects SAFA has chosen housing as its special theme in 2020. The given issue should definitely have been at the top of the agenda already many years ago. Unfortunately, SAFA has slowly lost the socially relevant and respected role that it used to have in the Finnish society in the earlier decades. Many efforts are made to turn the tide and the situation is not all that desperate.

Still, many fine new buildings

Contemporary Finnish architecture prides itself on several excellent examples of public or privately funded buildings. There are exceptionally talented studios and newcomer names. The architecture competition system is also doing well, even though it has been used as a tool to justify large amounts of construction volume for private investors. One example of this practise has been the Garden Helsinki project, loudly and deliberately pushed by Facebook urbanists and criticized by architects and many citizens.

To gain visibility for architecture, SAFA has established the Finlandia Prize for Architecture with the purpose “to promote the appreciation of high-quality architecture and to highlight the importance of architecture in producing cultural value and increasing well-being”. Recently the prize was given to the renovation on the “Käärmetalo” (Serpentine House) apartment building by Yrjö Lindegren, built in 1951. It has been excellently rejuvenated and meticulously repaired by Kati Salonen and Mona Schalin Arkkitehdit Oy.

Oodi, a new urban living room and library

When the republic of Finland celebrated its centenary, a whole building was given as a present to the nation and taken into use at the latter half of 2018. The new Helsinki central library named Oodi (Ode) is a competition winner by ALA Architects. It stands in the vicinity of the Sanoma House, Kiasma, the Music Centre and other buildings of Töölönlahti area, much criticized for its unambitious city planning. There were great expectations as far as the building as an urban living room and its future role in the cityscape were concerned. In terms of popularity, the building has actually exceeded all of them.

Oodi is obviously a building that was also deliberately created to boost Helsinki as a destination of Instagram tourism. It was said, of course, that its main purpose was to serve the population of the Helsinki metropolitan region as a reading, meeting and studying space. The entrance level includes a café, cinema and multi-purpose auditorium plus exhibition spaces. The second level of the building extending over a hundred meters contains spaces for study and meetings plus 3D-printers and sewing machines. The great book hall on the top floor with its large terrace is definitely highly photogenic. So is the entire building when bathing in evening light. The city of Helsinki and Archinfo have put a lot of effort in promoting its international visibility and popularity.

Due to its extreme popularity, very few people or journalists have dared to criticize the building. However, the main space on the third level is rather noisy. Some of the programming has not been done too well; there is no cloakroom and there are no lockers. People wandering about in their overcoats and with their shopping bags, plus giggling tourists, give the house an atmosphere of being a bit like a shopping centre. Even so, people definitely should not miss it during their visit to Helsinki.

Amos Rex

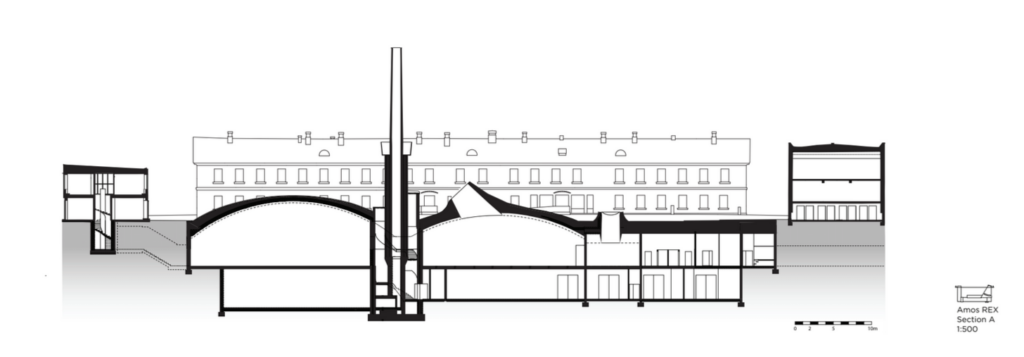

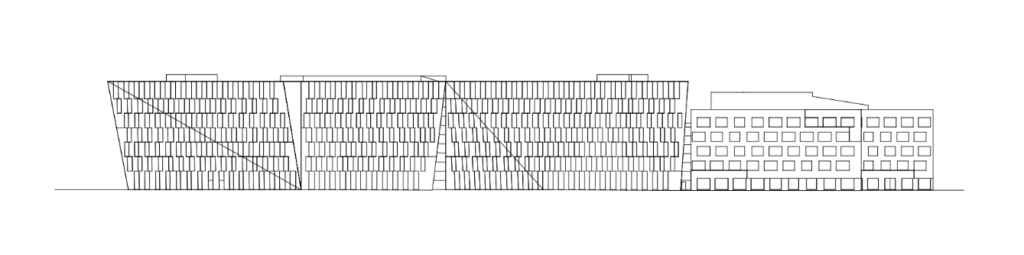

Another new building in the very heart of Helsinki is the Amos Rex Art Museum inside and behind the functionalist Lasipalatsi building from 1936 by Viljo Revell, Heimo Riihimäki and Niilo Kokko.

The museum, earlier called Amos Anderson Art Museum, required new spaces and decided to create them as an extension to the white two-storey Lasipalatsi building that almost all locals know and love.

Amos Anderson’s Föreningen Konstsamfundet Association that backs the museum gave the commission directly to JKMM Architects. With Asmo Jaaksi as the project architect, the office has created an adaptable and flexible underground museum exhibition underneath the Lasipalatsi Square in the former location of Helsinki bus station and terminal. The museum programme also includes a children’s workshop space.

Since the opening in 2018, the museum with its exhibitions and events have been enormously popular. The public has also taken the museum roof into active use, that is, the artificial hill or dune formations with their round windows in the pavement. The museum includes the restored and technically updated Bio Rex cinema with its 590 seats and beautiful foyer, also used as a venue for events, receptions and projects. The museum shop and ticket office are on the street level while the foyer, cloakroom, lockers and bathrooms are underground behind a handsome staircase. The exhibition spaces have been used highly effectively and similarly offer immersive experiences. For the exhibition of the artist Birger Carlstedt, a special café Le Chat Doré was created as a part of the extensive exhibition.

The artificial hills with their round skylight windows are now among the most photographed objects in Helsinki. They have also landed in the architecture comic book by Kari Kuosma, nicknaming it Amos Räx, as there are no movement and expansion joints between the organically shaped tiles. The museum has recently received the highly appreciated Leading Culture Destinations LCD Prize, considered to be “the Oscar in the field of museums”.

Vaaralanpuisto day care centre

AFKS Architects is a younger generation office based in Helsinki that excels particularly well at school and day-care buildings. They have recently designed an all-wood Lapinmäki day care building in Southern Haaga in Helsinki. In Vantaa, the Vaaralanpuisto day care centre has recently made it to the shortlist of the grand Finlandia Prize for Architecture, and definitely for a reason.

The building is located in a quiet suburban housing area and carefully situated on the plot so as to save the magnificent old trees. Therefore, the largest window-openings are facing the north overlooking one part of the playground area. On the south side, there is the parking lot and one of the many entrances.

The outside of the building is clad in dark brownish wood panelling. The core of the building with its porous space program is built with in situ concrete. Furnishings like lockers and closets in natural-coloured wood give the building a particularly homely and pleasant warmth. Important elements in the exterior are the metal staircases, painted in elegant but not overly flashy colours. The interior is full of exciting diagonal glimpses into adjoining spaces and with its openings and indoor windows, cleverly reminds us of a rectangular-diagonal version of Swiss cheese.

Materials are of fine but also honest rough quality. The architects have cleverly avoided making this building “childish”. The joyous daily communication and collaboration between children and staff can be immediately sensed and the low-key colour scheme leaves room for children´s own artwork and creations. The house and its multipurpose hall are also open for neighbourhood activities in the evenings. With a tight budget, the architects have created a small-size gem.

The K-Campus and OP Bank Headquarters

One of the most admired corporate interiors from recent years is that of the OP Bank office building by JKMM Architects. Fantastic architecture photographs of the interior spaces and the second level restaurants have ended up on the covers of architecture publications, and for a good reason. The whole building is definitely a visiting card for the bank.

A newcomer in the JKMM series of high-end spaces for work and businesses is the K-Campus or head office for Kesko in Kalasatama area next to the currently uncompleted towers and the shopping centre Redi by Helin & Co Architects. The K-Campus building fills up the entire perimeter block and acts both as the workplace and showroom for both K-products and services. The architecture is intended to be timeless and very Nordic. The facades are made of glass and rough seamed cream-colored bricks, with wood and concrete. In the centre of the building, there are a spacious atrium and inner stairwell that bathe in the daytime natural light.

The new work environment concept allows for different modes of working – from quiet concentration to interaction and teamwork. Each floor has its own cafes and kitchens. The interior designer Paula Salonen even won last year´s national prize for interior architects.

Energy-efficiency has been one of the main themes in planning and building K-Campus. Artificial intelligence is utilized in adjusting the building’s heating, lighting and air conditioning in order to maximize energy-efficiency and user-friendliness. In addition, K-Campus is the first office building in Finland that has carbon neutral waste management. BREEAM and WWF’s Green Office environmental certificates are applied for the building.

Jätkäsaari School

Finland is developing a new learning philosophy that encourages young people to learn by themselves. The idea of a teacher standing on a podium and talking to a class that sits quietly and listens is considered to be old-fashioned. All new schools tend to rely on a more open plan, but very little research has been made as far as the results in contemporary learning environments are concerned.

In Jätkäsaari, a former harbour area in Helsinki, a very compact and urban solution for a new kind of a school was needed. The architecture competition winner was AOR Architects, an up-and-coming name in Finnish architecture. The building is rectangular by its plan and has a slightly uncommunicative-looking white concrete façade with hundreds of smallish square openings. To break the monotony, there also are protruding balconies and terraces for pupils and teachers. In the streetscape, the building may at first sight appear very rigid and almost uninviting. But there are also open views through large glass surfaces into some classrooms or workshop spaces from the surrounding streets.

The interiors with the generous atrium are of an exceptionally high standard and quality. Fixed furnishings were created and designed by the architects themselves and made in solid oak or ash. There are several kinds of spaces for altogether 800 pupils, open and flexible and more fixed and tailored. It can be sensed that the architects have deliberately made more than just one excursion to Switzerland and been very observant during their journeys, as they value the Swiss striving toward perfection. The elegance of the meticulousness of the overall idea and the somehow timeless quality of the entire building are remarkable. No wonder that the rather young office has already won several prizes. Another school, also a competition winner by the same architects, and this time built in solid wood will soon be realized for the community of Tuusula.

Villa Riviera

Finland is well known for its lakes and summerhouses. Recently, many black or white minimalist, elegant and highly photogenic summerhouses have been designed for medium income or affluent private clients. Yet, among many highly publishable examples there is one that features particular originality as far as genial design, local materials and on-location construction are concerned.

Villa Riviera is located on an island in Lake Saimaa and naturally by a sandy beach. It has the genuine handwriting of architect Olavi Koponen, who is also known for other rather individual designs and his inventive use of wood and timber. He often takes active part in the construction. Today living in Grenoble, he has together with his partner in the office designed wooden buildings also on a larger scale.

The house is not exactly on the beach but instead discreetly placed behind pine trees and so that the undergrowth, moss, berry bushes and beautiful fluffy lichen will remain unharmed. The clients wanted a place where they can withdraw to relax and invite their family and closest friends. The collaboration between Olavi Koponen and trusted builders has made it possible to create a highly individual house that overlooks a fantastic lake-scape behind the trees but does not shout about its existence.

The villa oozes comfort, homeliness and proper Nordic simplicity. Wood has been used in many practical and playful ways. Due to the brilliantly beautiful location, there are balconies and outdoor stairways under the generous roof. The roof has some openings that show the basic bearing construction that is also visible in many parts of the building.

Challenge

Finnish architecture seems to be heading – as far a housing is concerned – into a very rigid direction. Some say it is a sign of going back to classicism. The optimized budget of the construction company makes facades turn dark, dull and repetitious. In the worst of cases, even balconies have disappeared. Maybe it would be worth going back to the previous situation, where there were a wider variety of construction companies of different sizes. Now the building branch is too much concentrated in the hands of a few.

But there is an even bigger challenge that must be vigorously looked into – experimental affordable housing for different ages and social groups. After the Corona virus threat has passed, there definitely must be some rethinking of completely different and truly sustainable urbanisms – also in cities and towns of smaller scale. The problems of Finnish architecture do not lie in the field of public buildings. The genuine challenge is in housing and how we live in a more urbanized society. We must develop alternative ways of living affordably, sustainably and more collectively – and with enough space to do different and even creative things indoors. Working from home – as we now do because of the virus – requires space, peace and other qualities that recent trends do not provide.

Too many new apartments are too small and way too expensive to buy or rent, and not only in Helsinki or Tampere. On the other hand, the “value” of even well-constructed buildings is dropping in the provinces. Now it is high time for our politics and politicians to take a closer look at what is actually happening and will happen in the future to our “national property” that is very much tied in buildings.

TARJA NURMI is a Helsinki-based architect, architecture critic and author of documentaries. She has recently established the architecture and film festival Ark Rex in collaboration with Amos Rex art museum. She has been awarded the Mark of Distinction by SAFA (2005) and the medal of the Knight of the Order of the Lion of Finland (2010).

Header: Helsinki Central Library Oodi. ALA architects, 2018. Photo Tuomas Uusheimo.

Published in Maja 2020 spring edition MAJA100! (100).