The greatest challenge for Estonian towns and rural municipalities is to move from governing to enabling. An enabling locality facilitates its residents’ initiative and cooperation between local actors.

Communal co-creation

A few years ago, Kaisa tried to figure out how to increase people’s faith in cooperative action in her local community of Anija. As her husband runs a technology company, Kaisa is well familiar with the logic of the IT world. For instance, with the principles of agile development according to which you work out a long-term plan but get down to business with the test version immediately. The product or service is gradually fine-tuned based on the continuous user feedback.

Kaisa translated the given approach into communal activity and organised Anija Lüliti1. It is a communal cooperation accelerator collecting ideas from local people on how to improve the community. The local panel of experts then analyse if the proposals are feasible and represent public interests. Next, teams are put together and equipped with respective tools and means. It all leads to a 12-hour day of action with each team implementing their idea. In two years with the support of the municipality and local entrepreneurs, Anija Lüliti has reconstructed playgrounds, parks, kindergarten yards, classrooms and bridges and discussed among other things also on environmentally sound waste management. Both times, around two hundred people were involved. Indeed, many of the projects should have been the responsibility of the municipality. However, if there is will and energy, then the role of the local government is not to hinder but to enable.

There are various other similar forms of communal cooperation. At the 48-hour creative hackathons Vunki Mano2 organised by the Development Centre of Võru County, entrepreneurs, residents, experts and public officials develop and promote local proposals. Both financial and motivational nudge has been given to dozens of ideas such as the establishment of Rõuge Remote Work Centre, saving Võru language from extinction, finding work for people with special needs, community transportation and supplying schools and kindergartens with organic food.

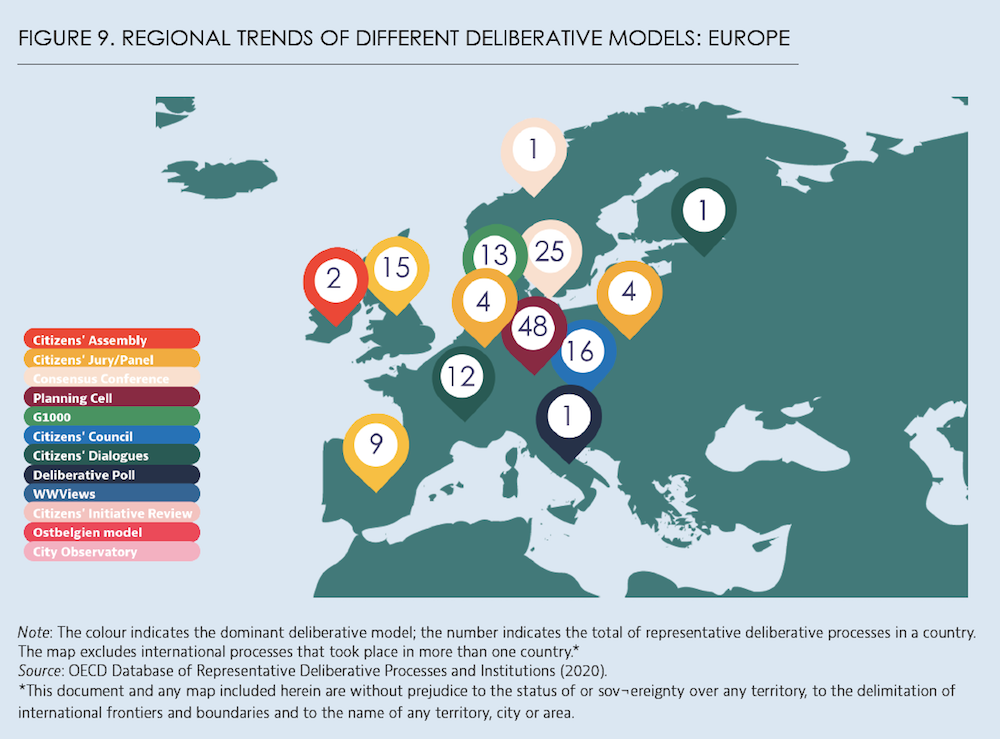

In European cities, collective solutions to climate and urban design problems are worked out by means of citizen assemblies3. The more complex the issue, the better it is to shape the solutions through science-based learning and common deliberations. In citizen assemblies, informed decisions are made by the randomly selected mini-public with every citizen having equal opportunities to get selected. The proposals will be implemented by the city government. Compared to traditional engagement of stakeholders and citizens, the given approach does not aim at reaching as many people as possible, instead, they wish to make informed decisions after drawing on expertise and discussing the problem or issue4. Thus, citizen assemblies are a good way to bring together and promote existing knowledge. In the Polish city of Gdansk and various regions in Belgium, such democratic innovations have become a permanent practice, while in various European cities, it is used for finding solutions to urban planning issues, such as how to reduce car traffic. Such co-creation in the public interest has not yet been tested in Estonia on the local level, however, we do have experience on the state level.

Participatory budgeting that is now used in over 20 towns and municipalities in Estonia5 and is launched also in Tallinn for the first time this autumn could be considered as a similar format. Only the focus is on finding the best objects to invest in. Participatory budgeting is considered the first and relatively simple form of democratic innovation. It differs from co-creation in its aspect of voting: the idea that collects the greatest number of citizen votes will be implemented. Partial opening of the budget is also spreading in Estonian schools.

The new local government reference system minuomavalitsus.fin.ee by the Estonian Ministry of Finance provides a projection of the level of governance that each town and municipality could have reached already. The indicators in the subcategory of an open, transparent and cooperative local governments include participatory budgeting, compliance with the principles of open governance, and the publicity of the work of council and government. We may ask why the residents’ activity subdivision includes only election activity and competition in councils. This is where towns and municipalities could suggest new indicators for the reference system by implementing and experimenting with novel co-creation opportunities and by establishing a reliable environment for initiative. For example, West Harju municipality can add its community board to the metrics as a way to enable to synthesise local problems and kick-start new ideas.

An enabling local way of life

The above examples describe a co-creative way of life. The kind of local governance where there is no real governance. Instead, there are formats and ways first to identify the problem or the unwanted situation and then design the solutions or desired situations in equal cooperation between citizens, public officials, entrepreneurs and other stakeholders. Such testing facilitates the implementation of jointly developed solutions and there is increased mutual trust and new insights6.

What is the role of local governments in an enabling and co-creative way of life? According to the recent Human Development Report, they provide a balanced deliberative space and create consensus, empower citizens7. Here we can also add the role of the protector of the public interest and common good, the promoter of a comprehensive forward-looking approach and also the funder, if necessary. The greatest challenge of Estonian towns and municipalities is to move from governance to enabling.

When focussing on the living environment issues, enabling entails a shift from the liberal approach to space to communal public spaces. Kristi Grišakov states in the Human Development Report8 that according to the liberal approach to space dominating in Estonia, the primary role of the public space is to provide an arena for consumption and private motorised travel subjected to individual benefits. Similarly, ‘the concept of the smart city of the future is also associated mainly with a liberal approach to space, where citizens ‘trade’ their data in return for the opportunity to use space or services’9.

A communal space, however, supports the citizens’ shared identity and amplifies it through various shared rituals8. With wise amplification, the local government can improve intangible factors considered as the foundation of contemporary social development: trust, safety, knowledge, reasonable habits10.

Technology as the enhancer of transparency and accountability

The global open government partnership movement11 nudges states and cities towards openness and transparency, co-creative practices and accountability. The focus is increasingly on the ways how to provide the means for accountable development of the future. The accountability of the local government is revealed in their fulfilment of promises in a democratic, open, ethical and sustainable manner. And in reporting of their activity.

Technology is a tool for co-creation and accountability, not an end in itself. Data allow evidence-based decision-making and boost new solutions to old problems, platforms based on feedback improve the compliance of (public) services with people’s needs, crowd-funding enriches (social) entrepreneurship, civic technology identifies and prevents corruption, citizen science provides researchers with valuable input, e-participation formats diversify the generation of solutions and help to track the fulfilment of the public promises made. Digital democracy injects co-creation directly into the bloodstream of the organisation of a society.12

We do not need to make things too complicated. Already today, urban mobility can be planned on the basis of data and spatial design projects visualised comprehensively. These do not necessarily require expensive augmented reality solutions or 3D models. Indeed, at one point also these will be part of the standard equipment. However, the main potential today is the way how the local life in towns and municipalities is collectively organised in keeping with the digital era. For instance, how to make local initiatives (kohalik.rahvaalgatus.ee) a common participatory method for citizens? Or how to collect immediate feedback from citizens in the same way as in ridesharing or courier services? Since, as said by the head of Governance Lab of New York University Beth Noveck13 , e-government and digital services do not automatically upgrade the society, instead, technology needs to be accompanied by processes, collective wisdom and leadership.

Actually, there is increasing talk of the need for governing technology instead. Concerns about the natural environment have arisen beside the traditionally tech-optimistic attitude. As stated by Jaan Aps, ‘Never mind the noble idea of the development and use of every single technological solution. People leading a more comfortable and longer life and acting more effectively and productively thanks to various technologies collectively produce, consume and pollute more than ever before.’14

Co-creative and communal way of life in towns, suburbs and rural areas allows to implement the requirements that we already have in Estonia: a compact and networked state, few people, a lot of space and nature. A systematic change requires the continuous enabling and orchestration of such a way of life. At the time of environmental crises, the main solutions lie on the local level.

TEELE PEHK is a democracy innovator and process designer of the Green Tiger. With long experience in conceptualising local and communal democracy, she has led various projects both in Tallinn and in smaller municipalities. Photo Meeli Küttim

Article is published in Maja’s winter 2021 edition (103, Smart Living Environment)

Header: A Citizens’ Assembly conducted with the random sample of 36 locals on the motorisation of the Old Town of Copenhagen in autumn 2019. The proposals by the Borgersamling became direct input for the City Government who is now actively dealing with the reduction of traffic in the Old Town. Photo We Do Democracy

1 Anija Lüliti: http://lüliti.ee/

2 Vunki Mano! https://vunkimano.ee/

3 Instructions for organising citizen assemblies on the local level: https://www.involve.org.uk/our-work/our-projects/practice/how-can-councils-engage-residents-tackle-local-issues

4 Innovative Citizen Participation and New Democratic Institutions: Catching the Deliberative Wave (OECD 2020), https://www.oecd.org/gov/innovative-citizen-participation-and-new-democratic-institutions-339306da-en.htm

5 Inclusive Budgeting Instruction (Rahandusministeerium 2018) https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwjk3afh3rjsAhXlsosKHSQHDIEQFjABegQIBBAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.rahandusministeerium.ee%2Fsystem%2Ffiles_force%2Fdocument_files%2Fkaasava_eelarve_juhend.pdf%3Fdownload%3D1&usg=AOvVaw14vam4nvA94JkCD_Dl34rk

6 About co-creation: https://koosloome.ee/

7 Spatial Choices for an Urbanised Society – Estonian Human Development Report 2019/2020 (Eesti Koostöö Kogu 2020), 9 and 18.

8 Kristi Grišakov, ‘Estonian Living Environment in 2050’, Spatial Choices for an Urbanised Society. Estonian Human Development Report 2019/2020 (Eesti Koostöö Kogu 2020), https://inimareng.ee/en/introduction-5.html#main-trends

9 Kevin Rogan, ‘The 3 Pictures that Explain Everything about Smart Cities’ (2019): https://www.citylab.com/design/2019/06/smart-city-photos-technology-marketing-branding-jibberjabber/592123/?fbclid=IwAR0wxR1RB5n9HicYYEuZfse_rjmm-0s37czDBnM-uMLGdv-qpCEIwvi1bRds.

10 Handbook of advocacy (Vabaühenduste Liit 2011), https://heakodanik.ee/sites/default/files/files/Hea%20Huvikaitse.pdf

11 opengovpartnership.org, avatudvalitsemine.ee

12 Teele Pehk, ‘Kuidas ületada konflikt esinduskogude, omaalgatuse ja koosloome vahel?’ (Edasi, 17 June 2018), https://edasi.org/26248/teele-pehk-kuidas-uletada-konflikt-esinduskogude-omaalgatuse-ning-koosloome-vahel/

13 Interview with Beth Noveck (ERR Novaator 30.5.2018), https://novaator.err.ee/835605/it-ekspert-rahvas-oskab-teha-rohkem-kui-korra-aastas-haaletada

14 Jaan Aps, ‘Tehnoloogia parema maailma heaks ehk kuidas taltsutada hunti lambanahas’ (Hea Kodanik, December 2019), https://heakodanik.ee/uudised/tehnoloogia-parema-maailma-heaks-ehk-kuidas-taltsutada-hunti-lambanahas/