SUURE-JAANI HEALTH CENTRE

Architecture: Alvin Järving, Mari Rass, Ott Alver, Kaidi Põder, Katrin Vilberg, Gert Guriev, Liina-Liis Pihu, Märten Peterson / Arhitekt Must

Interior architecture: Riin Kärema, Kerli Lepp, Mari Põld / Kuup Disain

Engineering: Teet Dooner, Anna Grishina / Novarc Group

Commissioned by: Põhja-Sakala municipality, Suure-Jaani Health Centre

Competition breaf: Toomas Paaver

Constructed by: Eviko (building), Kivipartner (outdoor area)

Plot surface area: 0.8ha

Building net surface area: 3100m2

Project: 2015-2017

Construction: 2017-2019

Careful homework on selecting the location for Suure-Jaani health centre, the wise decisions made by the local government as well as drawing together a number of public functions have provided the means for the emergence of very good architecture and the future town centre of Suure-Jaani.

Suure-Jaani and its new health centre are great places. Estonian small towns and boroughs have long been under the pressure of declining population and spatial shrinkage. This has largely been the result of the general trends in the society while, on the other hand, the situation has also begun to generate a new reality by itself. The employers claim that they cannot develop their business in small areas due to lack of labour force. People, in turn, wish to leave small places as there are no jobs. However, in the light of the general depopulation pattern, the number of jobs available is only one of the issues, while an important role is also played by the surroundings (both built and natural environment) and the availability of educational, healthcare and recreational services. All the above are vital for leading a good and comfortable life and there is no single template for the order and volume in which it should be developed.

The local government of Suure-Jaani has made a clear and bold decision to invest in the development of decent living standards and to provide the means for a better life with a new, modern and ambitious environment – all of which the health centre undoubtedly is.

A separate issue here is the programmatic layout of the new central buildings developed by the local governments of small towns. On the one hand, it seems reasonable to solve as many local problems as possible with one building where they could gather all the public functions in desperate need for new facilities. On the other hand, it also means that many buildings and spaces would thus be left redundant and the already limited number of potential tenants in the rental market will decrease further. Placing several important public services in one building and location could also have a paralysing effect on the rest of the urban structure, only intensifying its shrinkage.

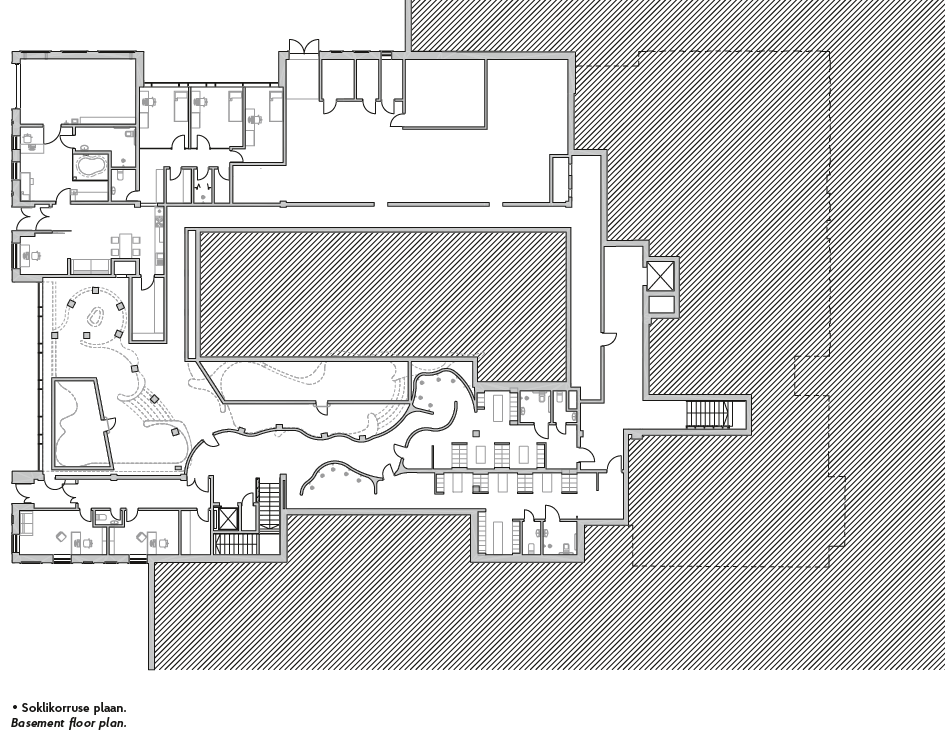

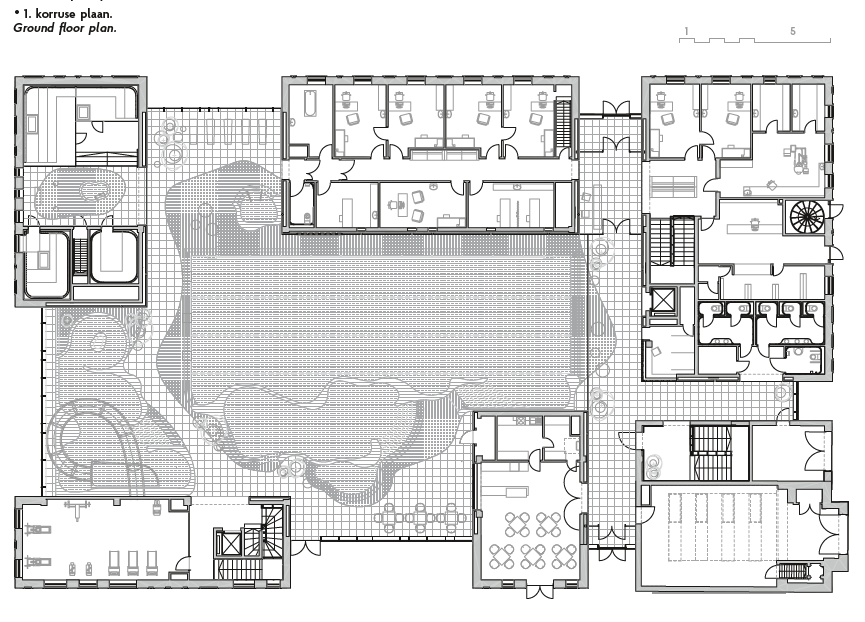

In addition to the swimming pool and saunas, Suure-Jaani health centre also includes a café, family health centre, dental surgery, drugstore, hair salon, ambulance and police station. Although it seemingly brings together a large number of institutions, each of them is just small enough to make placing them in different buildings around the town rather troublesome. Here they seem to have found a good balance between the number of services, the size of the building and the ways in which the small town functions.

In terms of architecture, the new health centre is a beautiful building. It kind of suggests that the project has not been pressed through the radical cheapening mincer (or more likely, came out of it more or less unscathed) that tends to be rather common in the design and construction process. The reason for that often lies in the client’s somewhat dim conviction that this time it must be possible to build it cheaper and faster than ever before, while sometimes it could just come down to the architect’s excessive bravado. Suure-Jaani health centre with its clear architectural ideas enthrals in terms of its urban design, logistics, functionality and materiality. It is indeed difficult to detach anything from a well-conceived assemblage.

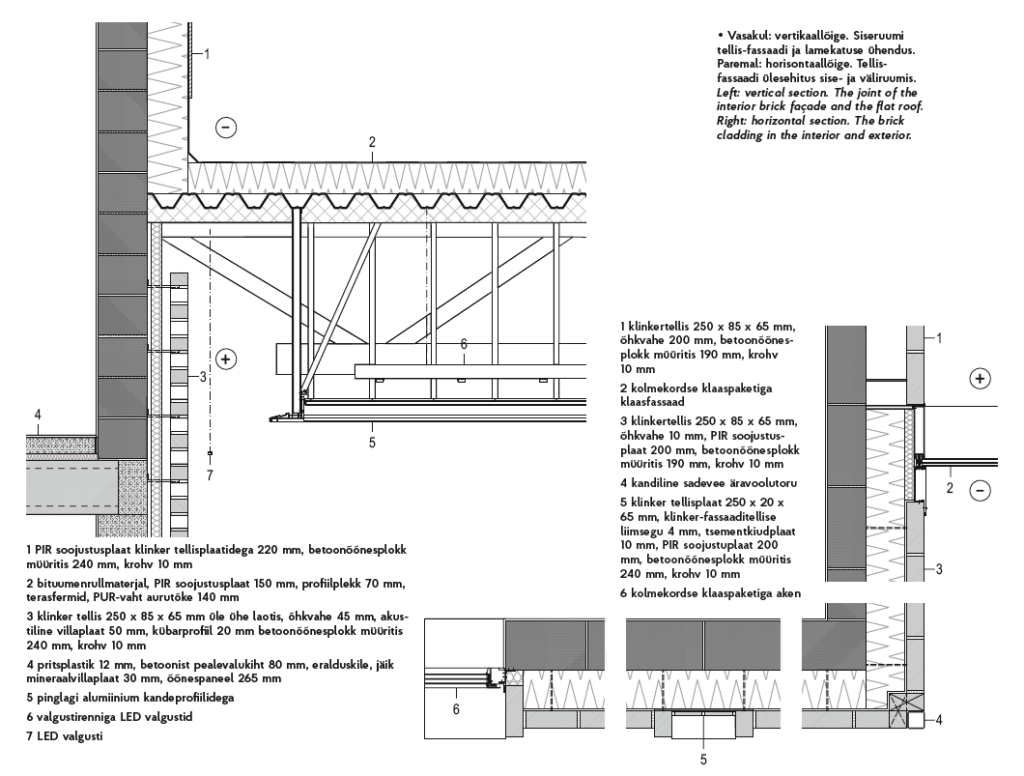

There are a few things to highlight. The division of the health centre into smaller houses reflecting the size, shape and use of materials characteristic of Suure-Jaani is a good idea that has also been given a clear architectural form in the completed building. The little red-brick houses are kept separate. The continuation of the brick wall from the exterior to the interior as well as the glass façade posts submerged into the wall structure are some of the small clever and well-considered details supporting the more general architectural concept. The perception of the space and the conveyance of the architectural thought are also enhanced by the different interior solutions of the brick houses and the faintly mystical feel of the pool area between them.

The material has been given a clear and clean treatment. The play with the red brick cladding leaving occasional larger gaps between bricks has solved the acoustic issues common to larger open spaces. The wet areas do not resort to the traditional ceramic tiles but spray plastic. This no longer conjures up images of the former bleak and cold bathhouses while also supporting the Soomaa atmosphere esteemed by the authors.

The same function is performed by the pool area lighting glowing behind the stretch ceiling reminiscent of a misty sky and also by the “squashed” end of the otherwise strictly rectangular swimming pool forming a nice extra space for relaxation. In this respect, the joint decision made by the client and the architects to prefer daily well-being and exercise to a four-lane competition pool is clearly commendable. This is precisely what the primary health care should provide for – disease prevention rather than competitive sports. The latter does indeed play a considerable role, however, the current solution caters for a larger number of people. As the ventilation inflow and outflow in the central pool area are skilfully solved behind the edge of the stretch ceiling ending right before the wall, the most important and largest space in the building has no visible grates. Among other things, this demonstrates the effective cooperation between the architects and interior architects as a result of which the spatial features and the selection of materials come to enhance the general architectural concept of the building.

For the townscape, the health centre has succeeded in creating a new comprehensive whole with its division into several smaller red brick houses quite characteristic of a small town. The common area covered in glass joins the houses without dominating the smaller sections while still integrating them into a new interesting entity. This is not a simple thing to do. The gable roofs of the houses resonate well with the formal language in the small town while the solar panel elements by the local manufacturer used in the roof pattern give it a generous touch of technological innovation.

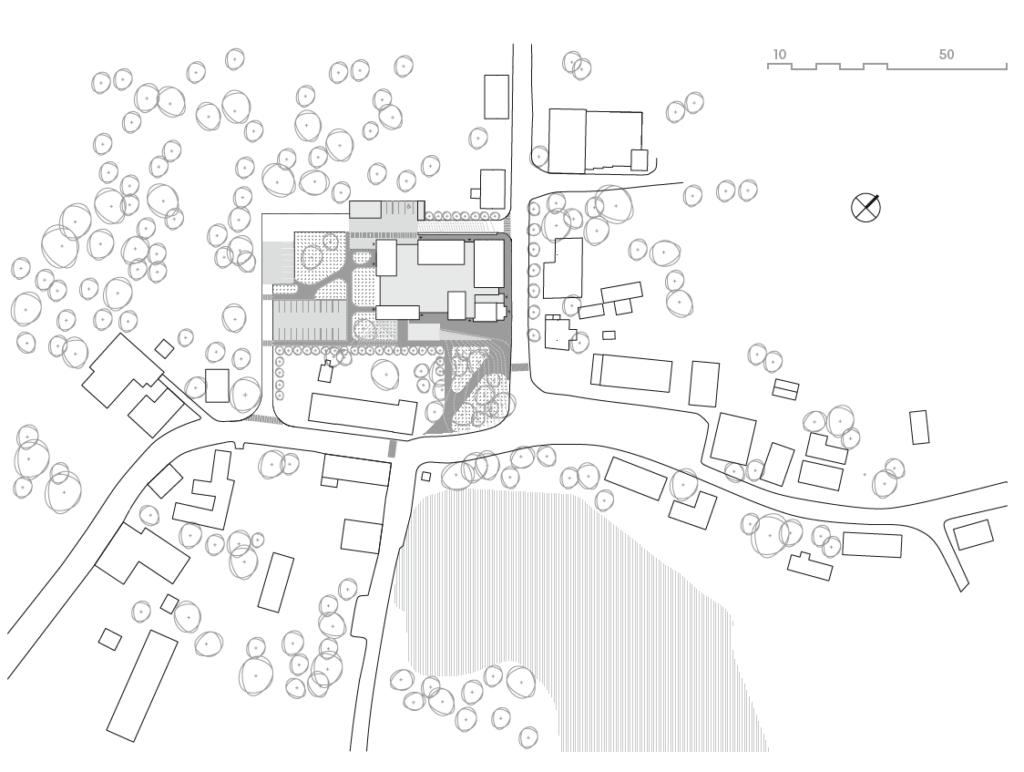

The location of the health centre is also a small triumph allowing the new building’s positive effect on the functioning of the small town to be felt probably for years to come. Situated along the so far only vaguely perceivable central square (the central place of the urban area), next to the artificial lake overlooking the church and in the future perhaps also the envisaged new recreational area, the health centre cannot escape anyone’s notice and will also afford its visitors various iconic views of the small town.

Thus an area is emerging in Suure-Jaani town centre that could resonate with the central square development programme “Great Public Space” even better than many of the projects completed so far. Classically rectangular squares bordered by a more or less uniform housing in their entire perimeter are very rare in Estonia. The traditional centres of Estonian towns and boroughs usually accommodate market squares emerged along the historical (trade) routes or otherwise somewhat more extensive spontaneous areas that have never been directly planned or constructed. Instead, they tend to be places with varying and at times also highly vague borderlines. Therefore, it is often more important to identify the local peculiarity in the background that is predominantly related with the surrounding building structure, landscape, cardinal directions and the established uses and to complement it with spatial clarity and quality. The health centre is an excellent beginning for the development of the central square in Suure-Jaani that seems to be ripe for further growth together with the music centre for the Kapp family of composers and the recreational area by the lake.

All the above also refers to a detailed and well-conceived groundwork that often tends to be overlooked while the lack of which will hinder the smooth and efficient progress both in the design, construction and the eventual use. That work is well evident in the architecture competition brief compiled by Toomas Paaver that includes an analysis of the possible locations of the envisaged centre and an adequate description of the current situation. These are neither lengthy or complex studies with scientific pretensions nor legal labyrinths to envision and exclude all evil but clear and concise architectural ideas. This way they benefit the architects participating in the competition the most and the given format could perhaps be followed also by the organisers of other similar competitions.

Everything seems to have gone well for Suure-Jaani health centre with the sensible and professional groundwork followed by a good project in the mutual understanding of architects and interior architects as well as reasonable construction – all this within about four years. Such harmony with no major deviations tends to be a rare fruit resulting from the efficient, systematic and wise effort by all parties that should be envied and set as a future goal. It is not enough to notice and praise good architecture, it is important to see and explain its mechanisms of formation in order to learn from it for the future.

TOOMAS TAMMIS is an architect and a professor of architecture at the Estonian Academy of Arts.

HEADER photo by Kristian Lust

PUBLISHED: Maja 99 (winter 2020) with main topic Rural Insights