There are tumultuous times in the seafront development in Tallinn with variously motivated changes. This is the moment when architectural institutions must perceive their sense of responsibility and contribute to the big picture with their expert knowledge.

Various projects have been devised for the harbour area in Tallinn for the past twenty years, however, the comprehensive whole has not been discussed with the inclusion of a broader group of planners, urban designers, developers as well as the general public. So far, the parties, i.e. the city, private owners and the port have not been able to express their goals clearly either. In terms of the diversity and openness of the process, the recent plannings of Tallinn harbour and the seafront conducted simultaneously serve as a good example of how a large urban area with considerable social implications should be planned and developed (considering the present possibilities and institutions!). From the point of view of the process, there is no great difference whether it is in state, city or private ownership. It is important that everybody has the opportunity to participate and make proposals.

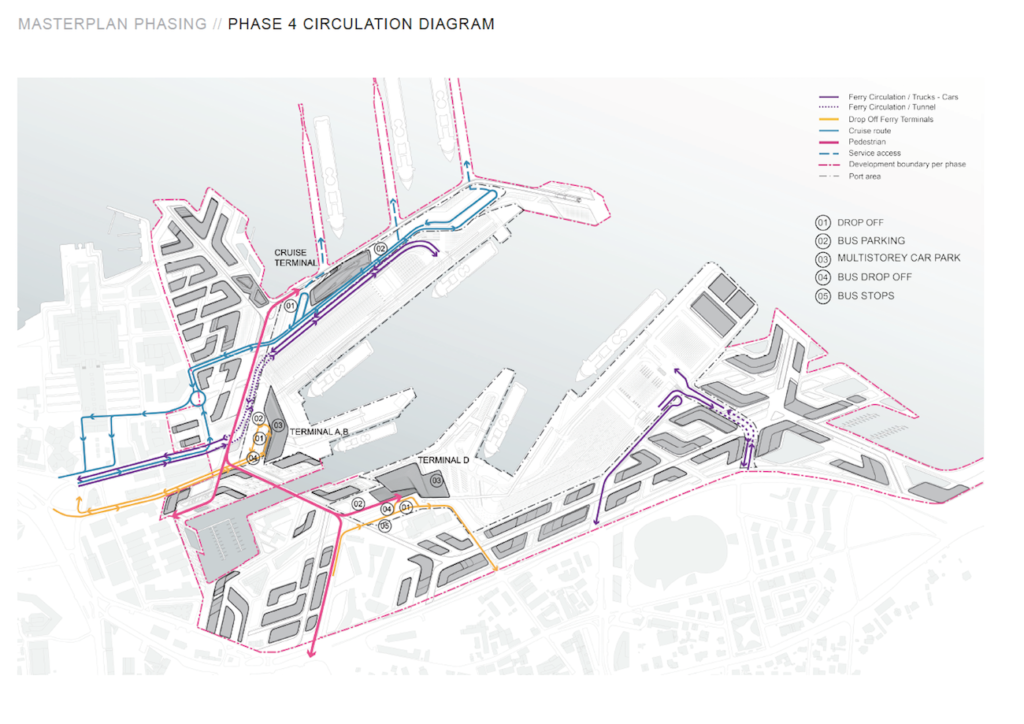

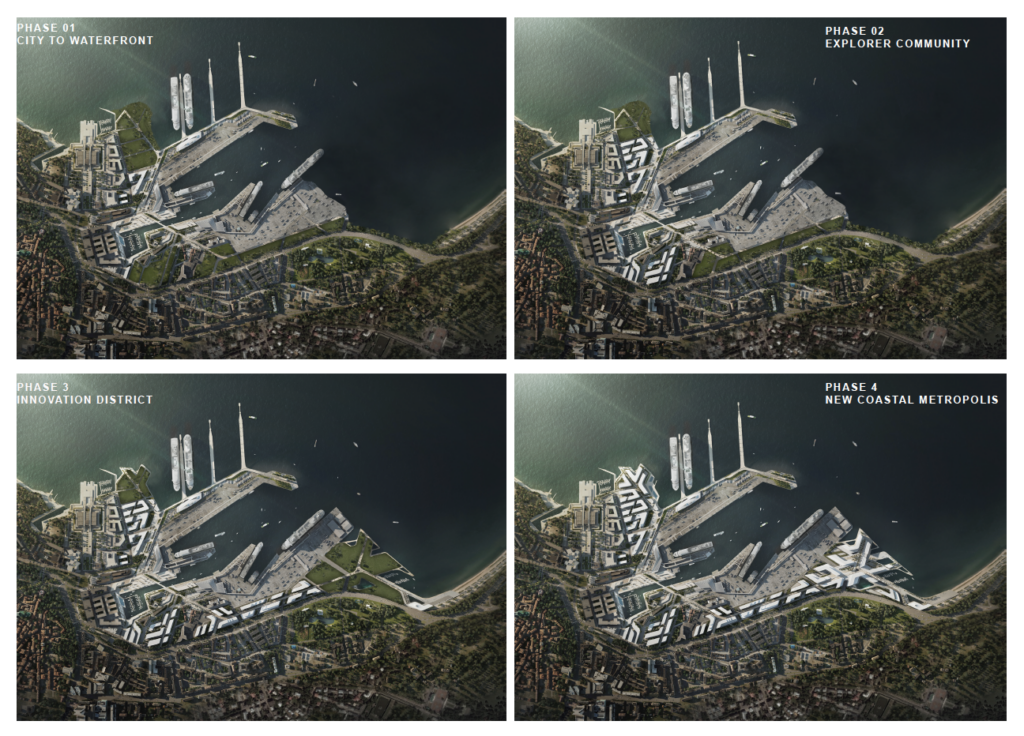

In the past few years, the Port of Tallinn has determined the necessary functional features: traffic volumes, the number of cruise ship piers, the arrangement of vehicle loading and the number of buses waiting. Drawing up the masterplan is a good interim stage to reconsider all the conditions at once. The city has completed the highly influential Reidi Road project. Independent of the port, the Architecture Centre in cooperation with the city government initiated a series of discussions on the concept for the seafront in Tallinn city centre followed by the vision including sketches and action plan, which could be considered also as a control mechanism for the developments in the harbour area. The fact that both the city government and the Port of Tallinn wish to take proper action in the seafront area with two respective public initiatives allows us to hope that there could be also joint results.

2016 summer: The Union of Estonian Architects (EAL) and Kalle Komissarov prepare a detailed competition brief for Tallinn Old City Harbour (Vanasadam) masterplan competition

2016 November: EAL appoints their representatives in the jury (architects Peeter Pere (EAL), Ülar Mark (EAL) and City Architect Endrik Mänd (city government)). The Port of Tallinn is represented by Valdo Kalm (CEO) and Hele-Mai Metsal (Head of Development).

2016 November: The Port of Tallinn in cooperation with the city and EAL announces the three-stage competition.

2017 January: Based on the portfolios, six entrants are invited to the second stage: Alver Architects OÜ, Arkkitehtitoimisto ALA Oy, City Form Office and KCAP Architects and Planners, Kavakava OÜ with and Alejandro Zaera-Polo and Maider Llaguno Architecture, Terroir ApS and Karres en Brands landschapsarchitecten b.v., and Zaha Hadid Architects.

2017 April: Three finalists are selected among the six anonymous works who are given a list of proposals by the jury.

2017 May: The finalists present their work and the solutions made on the basis of the jury’s suggestions and the jury provide further comments.

2017 June: The improved proposals are presented in the second meeting of the third stage.

2017 August: The jury’s final decision with Zaha Hadid Architects selected as the winner.

The Work of the Jury

While exploring the portfolios, the jury compared the quality of similar projects, the creative vision of the office and their ability to dwell into the idiosyncrasies of Tallinn. It was also important that the offices be different in order to exclude six participants with an analogous global handwriting. The criteria in analysing and assessing the six works in the second stage were more complex and the jury primarily focussed on the wide-ranging spatial idea and solid structure that would accommodate the inevitable changes in the future. One of the vital features of a masterplan is the definition of the traffic routes or streets. Similarly, the possible structure of plots is highly important. Everything else can be mended more easily, for instance, the volume of buildings may be changed with detail plans or design provisions, but there will probably be no considerable changes in the street corridors or the arrangement of plots in the next 100 years.

The work by Kavakava in the final stage was related to history proposing interesting spatial nuances. The road connections were well analysed, the directions of the most important streets opened to the sea and the seafront was cleverly intertwined with the urban space. The assessment did not benefit from the submission of two different proposals with the initial partner, all the more so that both works were incomplete. The core solutions were largely alike (for instance the street network), yet contradictory in the further developments of the volume. In case of their victory, other entrants would have had the right to appeal the decision due to the submission of two proposals. Such contestation of a public procurement would probably have been successful with the competition eventually remaining without a winner and declared a failure.

The proposal by Alver Architects suggested a good alternative solution with differentiated volumes for the plots along Reidi Road, however, it probably would not be possible to amend the given project to such extent. The key concept relied on the extensive linear park as a continuation of the bastion belt of the Old Town. However, there are already expanses around the Old Town and also the seaside is one vast public space. It is the area between the City Hall and the sea that would need denser and more diverse housing to avoid becoming a dead-end. The given entry proposed various iconic building volumes larger than the City Hall at the edge of the park next to the City Hall, with also a symbolic building on the eastern side of the Admiralty basin located unfortunately outside the harbour plot. In the long run, the city/state could consider the acquisition of the given area and the construction of such a building. Similarly, it may not be inconceivable that it is undertaken by a private entrepreneur, then again, it is highly unlikely that such cantilever housing would be allowed above the Admiralty in commercial interests. On the other hand, such a building is necessary for the justification and completion of the linear park.

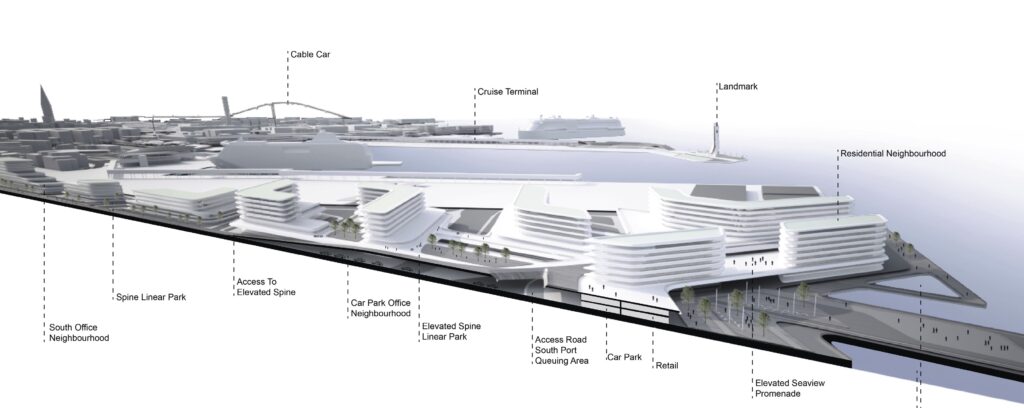

The strong points of the proposal by Zaha Hadid Architects included the merging of two diagonal connections into a square in front of the terminal and the well-considered harbour and traffic solutions. The most important connections remain in the south and west towards the Old Town. Then again, these were mostly similar or at least adjustable in all entries. The decisive aspect speaking for Zaha Hadid Architects was the connection between the east and west and the possibility of a beach promenade. The diagonals converging in front of the terminal are a clever find. Once the main connections and roads have been fixed, also the arrangement of smaller roads can be adjusted. This, in turn, will define the possibilities for housing and the plot structure. The solutions for the volume and the continuity of the street front needed some improvement and these were included also in the jury’s comments.

The City Forum after the Competition

In cooperation with the Port of Tallinn, Architecture Centre and the city of Tallinn, a city forum was organised on October 10-11. The aim of the event was to discuss the winning proposal and collect suggestions and recommendations. The forum burned with various opinions. The Architecture Centre suggested that the port invite also Andres Sevtsuk who participated in the second stage to analyse the winning proposal. Fortunately, the Port of Tallinn agreed to listen also to strong criticism in the name of developing the project. Sevtsuk’s respective analysis did not focus too much on the advantages, and the disadvantages were mercilessly catalogued. It would have been interesting to hear also his comparison with other entries, for instance, in terms of building volumes, the undeveloped land and building density.

Toomas Paaver discussed the differences between the seafront vision and the winning entry. In general, we may agree with the presenters’ criticism and the city forum format allow the respective working groups to further discuss the proposals and present them to the Port of Tallinn and the winner in writing. Due to its diversity and openness, the process should represent the ideal for the Union of Estonian Architects, however, there is a lot of criticism, tales and passion in the air. Why? Is it only because the victory was taken by a renowned foreign office or because it is such an important area? Or because there have been numerous competition and vision proposals for the area over the years? I hope that also in the future, important developments will be afforded the more complicated opportunity to initiate a constructive discussion needed for the society instead of the alternative in which the project is forced through with PR tricks and bureaucratic means. The haunting question remains – if the competition had been won by a well-known Estonian architecture company, would there have been more room for praise and would the criticism have been heard only in hushed, not to say closeted words?

Urban planning is a complex process with numerous variables. In the present situation, the organisations related with the field and the architects involved should acknowledge their responsibility and contribution in regard to such relevant issues as the future of the seafront of Tallinn instead of distancing themselves disapprovingly. There are tumultuous and curios, but what’s more, motivated events taking place in the seafront area: the recent Kalasadam competition, the sale of the City Hall, the Port of Tallinn competition, Reidi Road, the Main Street project, the next stage of Rotermanni Quarter, Porto Franco. Could the storm be perhaps too strong to stay the course? It seems as if architects did not want to sail tailwind of the given events at all. True, the waves and speed are high and the course unstable, however, now is the time for architects not to let go of the wheel, not to drop anchor or pass the wheel to the second mate.

ÜLAR MARK is an architect and urban designer. He has worked as the city architect of Narva, head of the Architecture Centre, President of the Union of Estonian Architects, curator of Venice Architecture Biennale and founder of Kodasema OÜ.

HEADER image: the competition entry by Zaha Hadid Architects.

PUBLISHED in Maja’s 2018 winter edition (No 92).