The city of St Petersburg, the largest metropolis in Northern Europe, is growing rapidly. But the architectural quality of the latest developments is rarely comparable with historical heritage. Can the cultural capital of Russia ever prove its nickname in the field of the art of construction?

Recent years in St Petersburg have been marked by constant complaints about the poor economic situation but also the ceaseless process of housing construction. The city is growing and needs more homes for people who prefer the cultural capital of Russia to the actual political and financial capital. Now the population of the city exceeds 5,360,000 inhabitants. For some people, the reasons for choosing Venice of the North include the beauty of the historical centre and the significant art/cultural scene, which is not as rich with all kinds of events and institutions as Moscow but contains a lot of non-commercial and truly original phenomena, such as AKHE theatre or PARAZIT art group, Pushkinskaya 10 Art Centre etc. The other motivation lies in economy. The real estate is significantly cheaper here than in Moscow. Preferring St Petersburg also means that the possibility of purchasing an apartment in Venice of the North is about two times less expensive than the one within the rings around the Kremlin towers1. People also move here because they seek a less active life than in the capital. In St Petersburg everything is slower than in Moscow, with both its good and bad sides, but besides rational reasons, there is something else which can be defined as a different raison d’etre of these two places. St Petersburg is a place where it is good to think, dream and create. But what architectural environment is being created for those who come here now?

Centre and Periphery

The life story of St Petersburg is still short but bright, and it came to be especially dramatic in the 20th century. The natural growth of the city was stopped by the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, and during the Soviet era the dichotomy between the old centre and the new districts appeared. Construction in 1920s was not very intensive due to the movement of the capital to Moscow, but already in Stalinist Leningrad, an ambitious idea of establishing a new centre for the city was introduced. This led to extensive construction in Moskovsky district in 1930-50s. After Khruschev reform in 1960s, the city started to grow in the northern and southern directions, which led to the return of the central role of the old town. This also created Leningrad per se: the new city around the historical core which turned into an inhabited museum. Leningrad is the largest part of the city: most of inhabitants live in post-war developments and the 1960s marked the peak years of the building process.

Generally, in Leningrad (differently from Moscow) the co-existence and confrontation of Soviet and Russian cultures were visually and spatially distinct: the alternative, non-conformist, underground culture tended to live within the old walls of St Petersburg, in kommunalka kitchens, paradnayas (staircases) etc and the intelligents who physically inhabited socialist mikrorayons, ‘khrushevkas’ and other standard series were in most cases dreaming of moving to the centre, where the true and uncorrupted culture could be found. You could go to the streets of Petrogradka or Vasilyevsky island, walk along Fontanka and Moyka rivers, and find yourself in a different time and space. You see the works of pre-revolutionary architects from all over Europe: Italy, France, Germany… “All flags were guests to us”2 in this former capital of Russian Westernization. To come back there, that was the Dream.

One of the best books describing the unique character of the Northern capital is Grigoriy Kaganov’s ‘St Petersburg. Images of Space’ (first published in 1995)3. The book is written by a scholar who had grown up in Soviet Leningrad and his book marked the period when the city was getting back its original name and it was again possible to speak freely about the old times. The book which is studying the ways of depiction of the city made by architects and artists (mainly by the latter) ends in 1990s, and it is worth noting that it does not contain any images of Socialist districts, although the total area of these territories was already bigger than old St Petersburg.

The last architect and artist featured by Kaganov is Mikhail Filippov. He is mentioned as an architect from Moscow drawing St Petersburg, but in fact he studied in Repin Academic Institute of Fine Arts in Leningrad, where the classical drawing tradition was (and is) still alive. Filippov’s watercolours usually depict the St Petersburg motifs in the technique which resembles the works of Alexander Benois or other representatives of Mir Iskusstva movement of 1920s. Kaganov emphasizes the fact that it is usually a motif but not a concrete view of a place or building. The critic talks about the “glowing vision of classical Petersburg”, “quiet shining of the eternal soul of St Petersburg”4 in the works by Filippov. But we can also find here a dream of St Petersburg that did not but could happen, Petersburg which could have grown continuously without the break of the Soviet era. The architect was speculating in 1990s: since the Soviet system is gone, what if we could come back to the development which was halted 100 years ago?

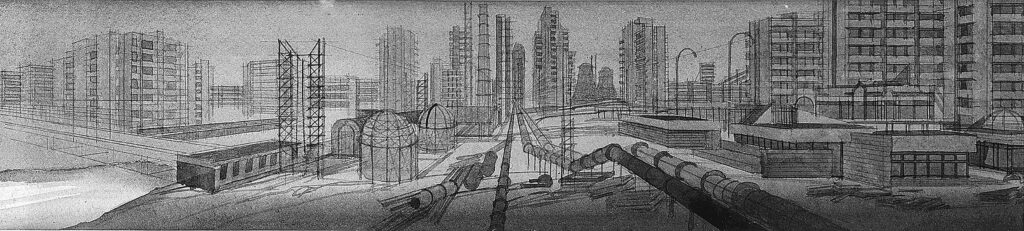

In this context, it is important to mention another work by Mikhail Filippov which was made even earlier in 1984, and which refers not only to St Petersburg but to any historical Russian city. In his entry ‘Style of 2001’ for the international conceptual architecture contest organized by the Japan Architect and A+U journals, he depicted the process of transformation of the failed utopia of a modernist city and rebirth of the old town with its churches, low-rise housing and green yards. This work reflects a certain postmodernist understanding of the future, seen as a poetic reconstruction of the past, which was especially strong in Soviet Russia of 1980-90s. This was a dream of post-communist and pre-neocapitalist St Petersburg.

From Postmodernism to Supereclecticism

This return from Soviet modernism to tradition was in some sense much more natural in St Petersburg than in Moscow, where the centre suffered from great transformations in the 20th century. But instead of what was depicted in Filippov’s pictures, we witnessed the progress of a sort of commercial pseudo-historic architecture, which was nicknamed ‘Luzhkov style’ in Moscow (after the mayor of Moscow) and ‘St Petersburg style’ in the northern capital (now, Luzhkov is gone together with his style, but ‘St Petersburg style’ is still alive, and you can see it, for example, in the names of the official architecture competitions). During 1990s, the first independent architecture bureaus were established and soon they became companies, controlling the market. Naïve and romantic postmodernism was rapidly turning into pragmatic capitalist realism (the term by Bart Goldhoorn), and finally mutated into what we call Supereclecticism of today.5

The works by such architects as Evgeniy Gerasimov, Sergey Tchoban, Evgeniy Podgornov represent superecleticism in a most explicit way. In short, SE is a current state of postmodern culture, which goes beyond postmodernism (and postpostmodernism). By using the term SE instead of metamodernism, we are trying to show that culture after the avant-garde has made a full circle coming back to its roots which were laid in 19th century. The style and idea of the pre-modern rationalism of this ‘Iron Age’ (to quote Russian poet Alexander Blok) was to use the forms and methods of the past but apply them according to contemporary needs and then execute them on an advanced technical level. The theory of eclectic method in architecture is set out in Entretiens sur l’architecture (1872) by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, a French restorer of churches. He was encouraging his contemporaries not to revive the past, but to know it and use it.6 Although le Duc was criticizing academism and praising Gothic art, his rationalist method of work was based on Cartesian bon sens.7 Since then the intellect has become the main criterion for the choice of a form, although this form still had to be beautiful and appealing (emotional).

The story of modernisation can be seen, on the one hand, as a continuation of Viollet-le-Duc’s logic, and, on the other hand, as an attempt to rationalise the irrational aspect of beauty (why was it Gothic?). The long journey of modern aesthetics brings us via avant-garde and expressionist experiments, art-deco and postconstructivist synthetic movements, postmodernism of 1960-90s to the situation of today, when, to quote the curator of Tallinn Architecture Biennale Reisner ‘beauty matters’ again, but it is a different kind of beauty, it is ‘not a singular idea, plurality prevails’. Paradoxically the opposite pole of the cultural and political discourse echoes this claim: Donald Trump’s recent manifesto (executive order) ‘Making Federal Buildings Beautiful Again’ produces the similar assertion – Beauties are back, indeed.

The Supereclecticism is a state of culture in which everything has to be included in the global ‘aesthetic empire’ and nothing should be excluded. Thus, modernist idealism can no longer be used as a source of ‘absolute architecture’ (and Piero Vittorio Aureli’s attempt to find foundation for the ideal form in the legacy of Mies does not convince at all). Modernism is just one of the possible styles in the frame of SE, and nothing more. Actually, perhaps it would be more precise not to talk about styles within this Grand Style of the epoch but formats (as we have on musical radio: jazz, rock, techno, classical etc).8

Back to St Petersburg context. The palazzo format in this context is something that is perhaps equivalent to classical or even light jazz radio stations. It is a type of architecture that is mainly purchased by the elite as a dwelling. Here we can primarily refer to works by Evgeniy Gerasimov and partners: residential houses ‘Venice’, ‘Pobedy 5’, ‘Verona’, ‘Russian House’, and the latest ‘Art View House’ by the Moyka River. These supereclectic edifices are characterized by an extensive use of natural stone décor and often on monumental scale. Studying the decorations, we can trace one of the main features of SE: the elements are copying the originals (from the Renaissance, the 19th century and Stalinist architecture), but the copy, executed by advanced computer technology, is more precise than the original. The digitally produced replica has a perfect shape, which could not be achieved by the hand techniques of the past. But it also lacks a human touch, or better to say Soul. This is ‘super’ per se. The ‘Russian House’ is especially important for this paradigm, here we see an eclectic building which reminds us of Pseudo-Russian Historicism of the 19th century, but this version is much bigger and has no vertical proportional variations. The back façade is pragmatically ‘modernist’, while the decoration of the front façade and cour d’honneur are made of fibro-concrete prefab panels, which repeat and repeat. Here we see the industrially produced beauty for rich people.9

In his interview to Project Baltia magazine, Eugeniy Gerasimov insists on the eclectic principle of work, ‘There is no such thing as good or bad styles, there are only good or bad architects’.10 In his portfolio, one can find not only historicist but also neomodernist hollandisms such as Megalite house facing the Neva River.

One of the constant collaborators of Gerasimov, Sergey Tchoban, an extremely successful architect working in Berlin, Moscow and St Petersburg, has a similar approach but produces variations of SE which possess a special kind of smartness. For example, his recent “Veren Place” dwelling in Sovetskaya Street forms a stylistic bridge between the two neighbouring houses: a building of the 19th century on one side and a postmodernist work by Studio 44 (another leader of St Petersburg architecture) on the other, trying to find a balance between the eclectic detailed façade of the older structure and plasticist formalist ‘cubism’ of a building which is shaped almost as a sculpture on the corner of the streets. Tchoban is creating a mediator, an ad hoc item, that links postmodern with premodern, stating a new type of rationalism.

Two more examples of SE. One of them shows that this trend can easily shape a neo-constructivist form. This is what we can see in the case of “Mendelssohn House” by Intercolumnium studio, which was recently added to the industrial ensemble, originally designed by a famous German expressionist in 1925. The Red Flag power station was refurbished while the new building was added nearby and waits for the functional reuse.

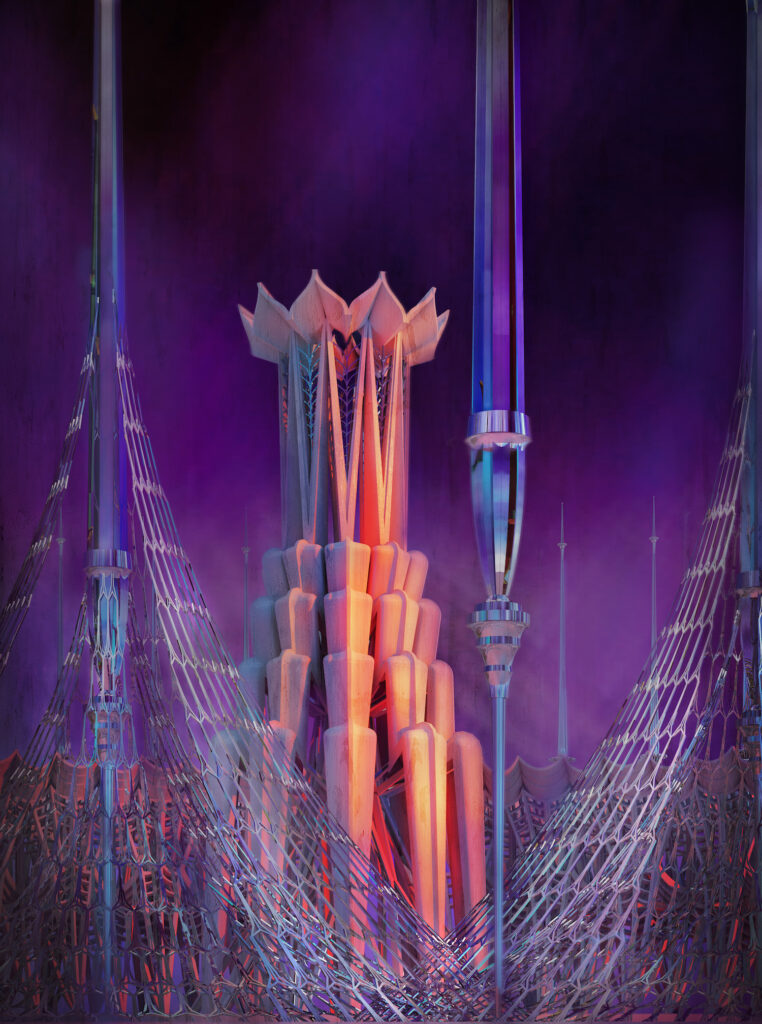

The other example shows that SE, as it was also the case with eclecticism of the 19th century, is not only a pragmatic and rational style but can also be romantic and poetic. This can be seen in the oeuvre of young architect Stepan Liphart who moved to St Petersburg from Moscow some years ago and is currently completing his first project, ‘Renaissance’ residential house on Dalnevostochniy Prospect. With its sublime rhetoric, this work refers to the architecture of 1930s and stands out from the junk space type surroundings of the newly built area. His visionary works made in his own digital technique, which produces an effect close the one of the cinema, serves as a sort of manifesto of the style. In this poetic version, SE is an attempt to let the machine work for the sake of beauty and the humanist ideal, despite the current triumph of mechanized rationalization and devotion to Superintelligence (computer). Liphart generates architecture that differs from Mikhail Filippov’s and his Moscow contemporaries’ speculations about the return of the Golden Age of the past, and produces a new heroic version of traditionalism, trying to get rid of the daemons of Capitalism or Political ideology.

Globalism and Metamodernism

The other trends which can be included in the Style of the Epoch but can also be represented as separate trends are globalist commercial architecture and all kinds of designs attributable to metamodernism. The first group consists of a large number of various business centres and glass structures that have more in common with car design than with architecture as art. Generic in mass, this type of urban development has its own unique examples, but this uniqueness is acquired through scale: Lakhta Centre by RMJM architects, which will open its doors this or next year is the tallest building in Europe (462 meters).

Both supereclectic versions historicist and modernist suffer from being attributed to kitsch and pop culture. One of the ways to get rid of this criticism is metamodernism which tries to play with a position between and beyond identities. In our opinion, one of its notable trends is New Nordic modernism (which is a combination of modernism of 20th century with new hollandisms and other global trends, and local (even national) stylistic trends). The leaders of this in most cases small scale architecture in St Petersburg are young offices KHVOYA and Rhizome. Both studios are extremely popular among the younger generation and often published in the global architecture media. It is sometimes almost impossible to tell if these nice barn-like or box-like structures are built in Russia, Latvia or Norway.

Part of the extensive work of one of the biggest and oldest private architecture offices in the city, Studio 44, led by Nikita Yavein, can also be attributed to this format, although the production of this company as we have already seen still has a lot from good old postmodernism, inspired by Aldo Rossi, Louis Kahn and Michael Graves.

Tсheloveyniks

The above-mentioned types and formats of architecture actually make up only a small percentage of what is being built. In mass, the post-soviet housing consists of 25-floor ‘inhabited walls’ or tcheloveyniks (human ant hills). The residential districts Severnaya Dolina or Murino have become targets of criticism not only from professional architectural circles but also from popular bloggers, such as Ilya Varlamov.11

People still buy apartments in such complexes, since they have little choice, developers are selling successfully and thus a Brave New City is being developed, a city where everything is under supervision and the freedom is given only in virtual space (and even here it is under control).

New Underground

When there is a feeling of pressure from the above, there are always currents that represent another pole – a sort of anarchist or radical cultures. In Soviet times, non-conformist and underground groups could be seen behind the official positivist architecture of Social Realism. They were partly controlled and partly suppressed by the state. Now under the media surface of supercapitalism supported by the State and transnational corporations, we can again find germs of free creative and radical thought.

Here we can mention two young bureaus from St Petersburg. The first one, Sever7, works in the field of contemporary art but also has a kind of fake architectural office ‘Woodman and Partners’. Its leader Nestor Engelke is an architect by profession. The group builds installations and take commissions to design private houses, which Nestor executes using an axe and a piece of wood. Their production is a gloomy sort of antimodernism. Shamanistic poetry of escape from the civilization, reaching a state of wild ‘village-like’ delirium.

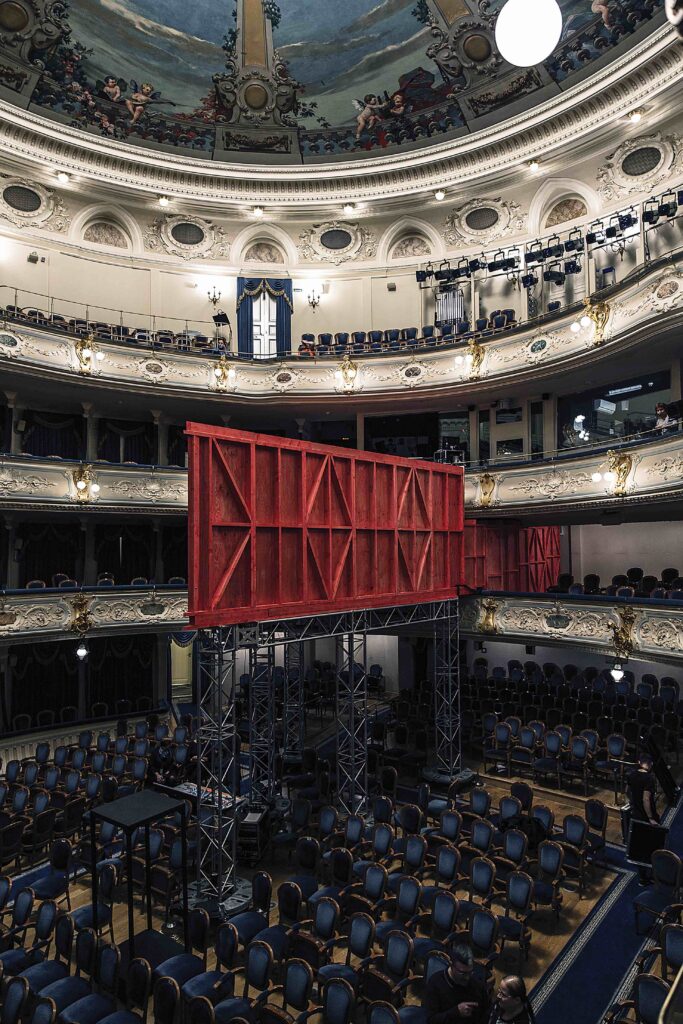

The other young team ArchAttacka is working in genres of conceptual architecture, critical design and dystopia but also produces small scale architecture and installations. The most famous work by the bureau, led by Andrey Voronov and Innokentiy Padalko, is PlyWood Theatre, a temporary scene for Big Drama Theatre in St Petersburg, made in collaboration with the artistic director of BDT theatre Andrey Moguchy and artist Alexander Shishkin-Khokusay. At first sight, the Plywood theatre which was in use within BDT for the entire year 2019 looks like a neo avant-garde gesture, an attempt to push out tradition ‘from the ship of modernity’. But on closer examination, the inner eclecticism of this installation is featured which contains references not only to 1920s but also to 1960s and other epochs. We are also unable to define the genre of this work: installation? Theatre? Museum (a tool to exhibit the old building and its elements in a special way)? Pop attraction? The best thing about this work by ArchAttacka is that it proves that the battle between the tradition and avant-garde is over, and now they are both on the same side, while on the other side one can see only a zombie-like ‘smart city of the future’ where there is no such thing as an artistic quality, and even no architecture as profession.

Epilogue

Indeed, in times of Superecleticism and new Aesthetic Imperialism, it is definitely hard to find fields that could lead to a Revival of the original St Petersburg architectural dream. But in our opinion, the only root is the identity of this city as an architectural utopia of beautiful (ideal) decorations built on the edge of the flat water surfaces. For Nikolay Antsiferov, the historian of St Petersburg who lived and worked in 1920s Leningrad, the mystery of the city on Neva River lay in the combination of heroic creative intention of the personified Genius Loci of the city (Peter the Great) and the miracle of the creative presence of Nature within the city, the ‘eternal struggle of the dream and naturalness’.12

Let us end this brief description of recent architecture in St Petersburg by mentioning the extremely young but already successful bureau Katarsis, led by Vera Stepanskaya and Peter Sovetnikov. They recently won several competitions, which have no connection in terms of organization or jury members, including ‘St Petersburg Facades’ (organized by the Committee for Urban Planning and Architecture, 2018), PromoArchDiz prize for young architects (organized by Project Baltia and French Institute in St Petersburg, 2019) and the installation competition of ‘Maslenitsa’ event in Nikola-Lenivets in 2020 (spring edition of the Archstoyanie festival). The huge installation ‘Burning the Bridges’ was constructed of dead wood by local farmers in the fields of Nikola Lenivets village to stand just for a couple of days, doomed to be burned on February 29th, according to the ancient festival tradition marking the beginning of Spring.

I was standing there in the crowd. When the fire was at its peak and the smoke had reached the darkness of the evening sky, the latter answered with snow, so the red and white dots of ice and coal were circling and dancing together, falling down on the wet brown ground covered with yellow grass, melting and leaving the naked surface of the field. Thus, winter kissed us goodbye, perhaps meaning, ‘I was here, even in this unusual snowless state, and now I send my snow to bless your festival and your architecture, your sacrifice’. Remember, Aalto once said that architecture becomes a work of art only when it acquires something from time and nature. If this architectural sacrifice was not a catharsis, then what else can this word refer to in the 21st century?

And here is how Katarsis architects define what true St Petersburg style means for them: ‘primarily good manners, restraint, intelligence, calm dignity and subtle perception.’13

Sounds not too progressive. But they do win competitions. The Dream is still alive.

VLADIMIR FROLOV is an architecture critic, founder and Editor-in-Chief of Project Baltia magazine, based in St Petersburg. He has curated a large number of architectural exhibitions shown at various professional forums, state museums and private galleries, including Arch-Moscow festival, Tallinn Architecture Biennale etc. Vladimir Frolov also gives lectures on modern and postmodern architecture.

Header: The Russian House residential complex. Evgeniy Gerasimov and Partners, 2018. Photo by Andrey Belimov-Gushchin.

Published in Maja 2020 spring edition MAJA100! (100).

1 https://www.cian.ru/stati-10-otlichij-rynkov-zhilja-moskvy-i-sankt-peterburga-218316/

2 Alexander Pushkin thus described Peter I’s idea of the open city.

3 Grigoriy Kaganov. Sankt Peterburg. Obrazy prostranstva, St Petersburg, 2004.

4 Op. cit. p. 227.

5 See also: Vladimir Frolov. The Limits of Supereclecticism. Project Baltia, no. 33 (4/2018 – 1/2019). Pp. 40-45.

6 Eugene Viollet-le-Duc. Besedy ob arckhitekture. In two volumes. Volume 1., M., 1937. P. 28.

7 See: Sergey Sitar. Archkitektura vneshnego mira. M., 2013. P. 176.

8 See article, where we write on formats in architecture (Vladimir Frolov. Wood after architecture in Project Baltia no. 29 (4-2016 – 1/2017), pp. 26-31) and refer to David Jocelit’s book After Art (Point, 2012).

9 If you happen to come and see it, do also check out the restaurant on the ground floor. It is an example of Super Russian interior design style (and cuisine).

10 Beauty is always liquid. Interview with Yevgeny Gerasimov. Project Baltia no. 23 (3, 2014), p. 67.

11 https://varlamov.ru/1869299.html

12 See: N.P. Antsiferov. Nepostizhimiy gorod. L., 1991. P. 157.

13 http://projectbaltia.com/down_news-ru/17698/