Adaptions: Estonian Architects Swept by the Winds of Transition 〉 Ingrid Ruudi

One More Museum, Please! 〉 Triin Ojari

School Revolution 〉Katrin Koov

30 Years of Apartment Building Construction in Estonia 〉 Indrek Rünkla

30 Years of Work 〉 Martin Pärn

The Culture of Congestion: No More Typologies or New Typologies 〉 Kaja Pae

Graphic Essay: Decades in Estonian Architecture 〉 Paco Ulman

A House is a House is a House? 〉 Mika Savela

Framework of Paide Process 〉 Andro Mänd

A Place for Learning to Learn 〉 Dina Suhanova

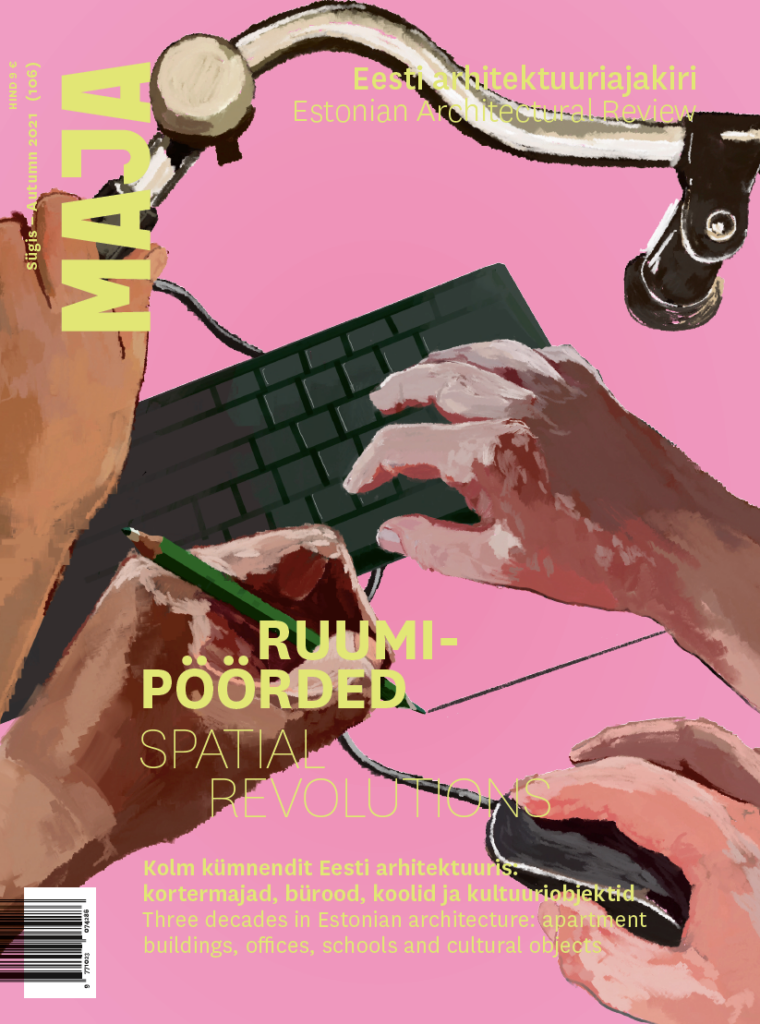

Spatial Revolutions

How does change in society reflect in architecture? In order to answer this question, we look back on the spatial design in the thirty years of regained independence. What kinds of spaces have accommodated us in the last three decades at work, in school and while enjoying culture? What have our homes been like? Since 1991, when the independence of Estonia was restored, we have stepped from what was essentially an agrarian society into the digital age. In the ‘90s, I used the horse-drawn hay rake as a means of economic activity, while today, I carry more computing power in my pocket than was had by the supercomputers of that decade. Have there been equally essential transformations also in architecture? Observing how our offices, general education schools, cultural objects and apartment buildings have changed, we can indeed say—with some qualification in regard to apartments—that the transformations in architecture have been almost as essential.

The kind of architecture that does not only accommodate practical necessities, but has been given more creative and budgetary freedom, more air, also tends to be more daring. As it can be expected, cultural objects in particular tend to have more of this sort of freedom of expression, self-awareness, and, ultimately, more responsibility. Changing values are graphically reflected also in the design of schools and office spaces. The central themes have radically changed—while in the 1990s, schools expressed aesthetically and figuratively a certain longing for a different, more realistic world, in the 2010s, the focus shifted to students and the properties of school as an environment conducive to learning. Common areas for socialising that emerged already in the ‘00s kept developing further in the ‘10s, looking to accommodate different types of personalities. Classrooms are no longer furnished as strictly and hierarchically as before; educational buildings are increasingly seen as community centres; the arrival of a new generation of landscape architects has led to more emphasis on outdoor and mobility spaces.

These developments in spatial design should not be seen as unidirectional and evolutionary, of course. For instance, there is a certain longing today for a new, digitally hybridised agrarian age, or at least a more natural environment. Likewise, buildings of a clear-cut type are once again giving way to buildings that combine initially unexpected functions. It is difficult to narrate the recent history in any other form than an explanation of how we got to where we are today, which can easily give the impression that our current priorities are somehow superior and self-evident. But as Walter Benjamin said, the dead ends of history have their own value. We don’t remember it so vividly anymore how it was to work in the rebellious and euphoric offices of the ‘90s and ‘00s, but their images carry a certain charge of invigorating utopianism, which is more captivating to the imagination than the offices of the last decade, which focus namely on questions like how it is to work, how to be satisfied, and what comes after the euphoria. And euphoria, as we have known it up to this point, indeed seems to be coming to an end. But what will carry us forward? We are increasingly speaking of evidence-based practices and user-centricity, but this only concerns our current needs and does not provide an answer the question—what is our common future going to be like? Insofar as we believe in architecture, we believe in its power to bring together various social issues and answer this question by exploring different possibilities or opening up visionary and unexpected perspectives.

This is our tribute to the 100th anniversary of the Estonian Association of Architects, 30th anniversary of Museum of Estonian Architecture, and to the Republic of Estonia, whose thirty years of regained independence have made all these changes and all this culture possible. Maja joins the congratulations!

Editor-in-chief Kaja Pae and Editor Urmo Mets

October, 2021